KEY TERMS

Department of Homeland Security

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

Model State Emergency Health Powers Act

National Incident Management System (NIMS)

Office of Emergency Management (OEM)

The events of September 2001 confronted the United States with a new awareness of vulnerability. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon made clear that the nation was threatened by enemies who wished to terrorize it using nonconventional weapons and that military and intelligence agencies were unequipped to defend against them. The anthrax-containing letters sent through the mail, while causing only minimal loss of life, exposed a threat from another nonconventional weapon, suggesting the equally terrifying possibility of epidemics for which health agencies were unprepared. The successes and, mostly, the failures of the nation’s response to these events forced national soul-searching and mobilization of resources to ensure that the United States would not again be caught by surprise. However, the nation again proved to be unprepared in August 2005, when New Orleans and the surrounding areas were hit with a natural disaster in the form of Hurricane Katrina. Despite extensive planning for emergencies by federal, state, and local governments, especially after 9/11, it became apparent during and after the hurricane that important segments of the New Orleans population had not been considered in the plans, with tragic consequences.

The plane crashes and the intentional spread of pathogenic bacteria required law-enforcement responses aimed at identifying responsibility, punishing the perpetrators, and preventing further harmful actions. These events also prompted public health responses to deal with the consequences of the incidents and to prevent further injury and illness. In responding to natural disasters, such as hurricanes, public health has always had an important role. However, important lessons have been learned from the failures of Katrina, and it is hoped that further planning will better prepare the nation to deal with future emergencies of all kinds.

Types of Disasters and Public Health Responses

Disasters cause death, injury, disease, and property damage on a scale beyond the routine emergencies to which the health system is accustomed. However, many natural disasters are predictable—for example, hurricanes, blizzards, and forest fires—and vulnerable areas generally have plans to deal with them—although the adequacy of these plans may not be obvious until they are put to the test. These plans usually include prior evacuation of the population in affected areas to minimize negative health effects and loss of life. Other natural disasters may be unpredictable, like earthquakes, but even these unpredictable disasters tend to occur in specific geographic areas—California, for example—and therefore allow communities to be prepared through strict building codes, requirements that appliances be secured, easy turn-off of gas and electricity, and so on.

Manmade or technological disasters are generally unpredictable, although the potential can sometimes be identified and the possibility minimized through government regulation and community planning. Typical technological disasters include industrial explosions, hazardous material releases, building or bridge collapses, and transportation crashes that may also cause a chemical or radioactive release. The presence of an industrial facility or a nuclear power plant should prompt a community to conduct emergency planning appropriate to the facility and the possible exposures. Detailed planning is more complicated for plane crashes and crashes of trains or trucks carrying hazardous materials, which may occur at unforeseen sites. Most terrorist events fall into the category of technological disasters. An act of bioterrorism could cause a disaster, but it would be expected to mimic a natural disease outbreak and demand the same public health response that a natural epidemic would require.

Most disasters, natural or manmade, cause immediate injury to many residents of the affected area. Sometimes specially trained and equipped rescue personnel are needed to locate and extricate people buried in the rubble of collapsed buildings or to move people out of harm’s way in fires or floods. Police and firefighters are often on the front line in combating a disaster. The injured require emergency medical care and transportation to hospitals. If hazardous materials are involved, measures must be taken to protect the rescuers and medical personnel. The situation can get even more complex when volunteers join the rescue efforts. In some cases, family members might be wandering around anxiously searching for loved ones. These individuals may also need protection from hazards in the affected environment. When there are many deaths, procedures must be established to identify victims and to communicate with their families. In situations such as this, there is a critical need for coordination of activities.

Disasters create conditions that cause health risks for the survivors. These tend to be amplifications of the general environmental hazards that public health deals with routinely: contamination of air, water, and food; exposure to toxic chemicals or radioactivity; and injury hazards such as fallen power lines and unstable buildings. The survivors need food and potable water; some people with chronic diseases may urgently need medications such as insulin or cardiac drugs. People may be left homeless by the disaster, or they may be displaced and need temporary shelter.

What is the role of public health in all these activities? One of its most important functions is planning in advance of the emergency, working with other agencies to ensure coordination of all the activities of the responders. Local public health authorities should be knowledgeable about the community and its resources because they have the responsibility to protect the health of the survivors. One of the outcomes of the 9/11 attacks was the recognition of weaknesses in coordination and communication of the emergency responders. This led to a concerted effort, organized by the federal government, to ensure that all communities have disaster response plans in place so that any future attack may be met by an effective response. This planning process is intended to have the added benefit of preparing the nation to deal with other natural or manmade disasters. In fact, many private and public organizations actively promote the need for “all-hazard planning.” Unfortunately, the response by all levels of government to Hurricane Katrina demonstrated the weaknesses in the previous planning.

New York’s Response to the World Trade Center Attacks

When two jet planes hit the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001, at 8:46 and 9:02 A.M., New York City police, firefighters, and emergency medical workers rushed to the site. The firefighters and police launched rescue and evacuation efforts, and emergency medical workers set up temporary medical posts to treat injured survivors. The city’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM) began directing activities from its headquarters nearby at 7 World Trade Center. Ambulances came from all over the city, and hospitals in all five boroughs prepared to receive large numbers of casualties.

Between 13,000 and 15,000 people were successfully evacuated from the towers before the south tower collapsed at 9:59 A.M. and the north tower at 10:28 A.M.1 Tragically, 2801 people died, including 149 passengers on the planes.2 The fact that so many people survived the disaster showed that, in many ways, the emergency response efforts were successful. Subsequent to the 1993 bombing at the World Trade Center, improvements in fire safety measures had been established, including better lighting in the stairways and evacuation drills. However, many things went wrong on September 11. The building housing OEM headquarters was severely damaged by the collapse of the north tower soon after the attack and had to be evacuated, significantly undermining OEM’s ability to coordinate the rescue efforts. Moreover, OEM’s communication depended on an antenna located on the roof of the north tower.3 The police department and the fire department each had its own radio communications system, but they used different frequencies and could not communicate with each other. Poor communication led to confusion for some evacuees when some stairways were blocked, and they were not informed of alternative routes down. Doors to the roof were locked, trapping people who worked above the impact sites and tried to escape by climbing upward. Tragically, the fire department radios worked only sporadically in the high-rise buildings, so, despite attempts to warn them, at least 121 of the 343 firefighters who died were in the north tower when it collapsed. They had not realized that the south tower had fallen.4

After the buildings collapsed, the air was filled with dust, soot, and smoke, posing a threat to the thousands of rescue workers, cleanup workers, and later, residents and people who worked in downtown Manhattan, who were allowed to return to their homes and offices. An estimated 5000 tons of asbestos had been released into the air due to the destruction of the buildings.5 Lead, other metals, dioxin, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were also detected in the soot, as fires continued to burn for months after the disaster. Although workers at the site should have been wearing respirators to protect their lungs, few of them did in the early days, and many of them developed the notorious “World Trade Center cough.” It was not clear which agencies were responsible for determining when the area was safe. A priority at the highest levels of government was to get the downtown area back in business, especially Wall Street, which was reopened only six days after the collapse. Politicians rushed to reassure New Yorkers that the environment was safe, but there was no scientific basis for these reassurances, and their statements were received with appropriate skepticism.6 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was accused of covering up the risk.

The Departments of Health of New York City and New York State had the responsibility to carry out routine public health functions, under not-so-routine conditions, during the period after the disaster. They issued death certificates and burial permits. They monitored food and drinking water served to emergency workers to ensure that it was safe. They cleaned up food in abandoned restaurants at the site to prevent outbreaks of rodents. Because there was concern that the attack might have included biological agents, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent officers to monitor hospital emergency rooms for patients with unusual symptoms. Later ongoing surveillance activities included sampling of dust and debris near the site to assess risk and monitoring of symptoms of cleanup workers and area residents. In addition to respiratory symptoms, insomnia, headaches, and dizziness, millions of survivors and workers suffered from psychological distress suggestive of post-traumatic stress disorder. Mental health agencies arranged for counseling. Victim location services were established for families with missing relatives, and shelters for displaced residents were set up. At least 19 city, state, and federal government agencies, as well as several academic, medical, and other organizations, were involved in the public health and medical response to the disaster.2

Response to Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was not a surprise. Hurricanes regularly make landfall along the Gulf Coast, frequently threatening Louisiana. Parts of New Orleans were flooded by Betsy in 1965, and the city was threatened by Camille in 1969, Andrew in 1992, and Ivan in 2004.7 Some 80 percent of New Orleans is below sea level and the city is essentially surrounded by water, bordered by the Mississippi River on the south and Lake Pontchartrain on the north, which is connected with the Gulf of Mexico on the East.8 The city is kept dry by levees, built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, that have long been known to be inadequate to withstand a major storm; funds for planned upgrades have been repeatedly cut from the federal budget.

Tropical Storm Katrina was identified and named on Wednesday, August 24, 2005, while it was in the vicinity of the Bahamas. On Thursday, August 25, the storm was upgraded to a category one hurricane as it passed through Florida into the Gulf. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) National Coordination Center was activated. On Friday, the National Hurricane Center forecasted that the hurricane would strike east of New Orleans, and Louisiana governor Kathleen Blanco declared a state of emergency. On Saturday, Katrina was upgraded to category three and several parishes and coastal areas were ordered to evacuate. Contraflow traffic was instituted on all highways in southeastern Louisiana, allowing outgoing travel only. Governor Blanco called into duty 4000 National Guard troops. Early Sunday morning, Katrina was upgraded to a category four storm; a few hours later it was upgraded to category five, with winds of 160 miles per hour. At 10:00 A.M., the governor and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin ordered mandatory evacuation.7,9

On Sunday morning, the Superdome opened as a shelter of last resort. Cars were leaving Greater New Orleans at the rate of 18,000 per hour, and the highways were clogged. By the end of the day, an estimated 80 percent of the city’s population of 458,000 had left, but over 100,000 people did not have a car and were unable or unwilling to evacuate. About 10,000 people were in the Superdome, and an unknown number were waiting in houses and other buildings in the region. Rain began to fall in the city around 9:00 P.M.

By early Monday morning, New Orleans was being pounded by wind and rain; power and telephone service had failed, and some of the levees had been breached. Generators provided dim light to the Superdome, but no air conditioning, and the air was stifling and stinking. Two holes opened up in the roof of the Superdome, which was a cesspool of human waste and garbage, lacking food, water, and medicines. In various parts of the city the water was 4 to 15 feet deep. People were trapped in attics and clinging to rooftops. The Coast Guard and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries began going around in boats, rescuing people and taking them to the Convention Center, which did not have food, water, or other provisions for sheltering people. As the day progressed, the hurricane began to move away from the city.7,9

As of Tuesday morning, there were 20,000 people in the Convention Center. Patients and staff members were stranded in New Orleans hospitals, all but one of which were without power, and conditions were deteriorating. There were dead bodies in the street, floating in polluted water, people drowned in their beds because they were old or disabled and could not get up and go to higher ground; others drowned in their attics because there was nowhere higher to go. In one nursing home that did not evacuate, 35 elderly or handicapped people died in the flood; five more died within a week, probably from the stress of the ordeal. Although some hospitals evacuated before the storm and others were on high enough ground to escape flooding, three of the poorest hospitals suffered through the storm in primitive conditions, in stifling heat, without electricity to run ventilators or other medical equipment; some ran out of food and medicines.7,9

As of Wednesday morning, 26,000 people were in the Superdome. U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Michael Leavitt declared that a public health emergency existed in the states affected by Katrina. At 2:00 p.m., buses began evacuating seriously ill and disabled people from the Superdome. On Thursday through Sunday, patients and medical personnel were evacuated from hospitals by helicopter or boat to a makeshift field hospital at the airport. Many patients did not survive that long.7,9

An accurate death toll from Katrina will probably never be known. According to a report by the National Hurricane Center, it was more than 1200.10 Most of them were poor and black. In fact, 68 percent of the pre-Katrina population of New Orleans were black, 23 percent were below the poverty level, and 21 percent lacked a vehicle, all factors that contributed to the high death toll.11 The majority of the fatalities were people who did not or could not evacuate ahead of the storm. This raises the question, why did so many people apparently ignore orders to evacuate?

Later surveys of survivors from New Orleans who were evacuated after the storm to shelters elsewhere found several common themes in people’s decisions. One study analyzed the findings according to the Health Belief Model (HBM).12 On the first factor in the HBM, the extent to which people felt susceptible to the threat, many long-time residents felt they could survive because they had survived many previous hurricanes without serious problems. Another source of optimism was religious faith; many people believed God would take care of them. The second factor in the HBM, the perceived severity of the threat, many interviewees reported that they were confused about the messages from the governor and the mayor. The early evacuation orders were not mandatory, and residents interpreted this to mean the threat was not severe. By the time the officials made the order mandatory, they said, it was too late to leave. The third factor in the HBM, the barriers to action, poor blacks perceived many barriers, financial, logistical, and community. Orders to evacuate were not clear on how or where to go. Even families that had a car may have lacked money for gas or worried about paying for necessities while traveling, or their family might have been too large to fit comfortably in the car. Family members who were old or had health problems made it difficult for the whole family to evacuate. Some people were reluctant to leave their homes without their pets, making it difficult even to go to a shelter. Some people were afraid they would lose their jobs if they left the city. Others felt they needed to stay behind to protect their property from looters.12–14

Many of those who stayed in New Orleans during the storm felt they were victims of racism. The feeling was reinforced by incidents in which residents of black neighborhoods were prevented by police from entering richer, white neighborhoods when they tried to get to safer ground. A rumor was going around that levees in poorer areas had been purposely dynamited to protect whiter, richer areas of the city.9 One later survey found that 68 percent of survivors thought that government would have responded more quickly if more New Orleans residents had been wealthy and white.13

The scale of the disaster was well beyond the coping ability of a single city or even a single state. Not only was 80 percent of New Orleans flooded, but widespread destruction occurred throughout southern Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Katrina turned out to be the deadliest hurricane since 1928 and the costliest natural disaster on record in the United States.15 Then, 26 days later, Hurricane Rita made landfall near the Texas–Louisiana border, interfering with hurricane-response activities in New Orleans and forcing evacuation of coastal regions of Louisiana and Texas, including some areas where New Orleans evacuees had taken shelter.

In New Orleans there was a desperate need for help from outside the city, a need that should have been filled by FEMA and the National Guard. Help from these fronts was tragically inadequate, for a number of reasons. Governor Blanco called up the Louisiana National Guard on Friday before the storm struck, but the ranks were depleted because 35 to 40 percent of them had been called to active duty in Iraq and Afghanistan along with much of their equipment. The troops patrolled the streets of the city, provided security at the Superdome and the Convention Center, and delivered what food and water were available. Eventually, National Guard troops from other states were sent to New Orleans to help with evacuation and cleanup.7,9

FEMA was a weaker agency than it had been during the Clinton administration, when it was a cabinet-level agency with a professional disaster-relief professional as a director. Under President George W. Bush, FEMA had been incorporated into the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, where the focus was on terrorism; its budget had been repeatedly cut, and it had lost many of its experienced staff.9,16 Moreover, its director, Michael Brown, was a political crony of the president, clearly incompetent for the job. Despite the notoriously untrue Bush remark on his visit to New Orleans Friday, September 2—“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job”—Brown was severely criticized in the press, by Congress, and within the administration, and he resigned in mid-September.9

President Bush himself was mostly absent from the early days of the crisis. He had been on an extended vacation at his ranch in Crawford, Texas, throughout August, and he had not seemed to pay much attention to the hurricane as it developed. On Tuesday, August 30, he delivered a speech on Iraq in San Diego, making only brief, reassuring comments on Katrina. He returned to Washington on Wednesday, declaring that he was cutting his vacation two days short. Vice President Cheney was on vacation in Wyoming.9

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita left many public health problems in New Orleans and the surrounding area, some of which are still unaddressed. Because most of the city’s population, estimated at 485,000 in 2000, was evacuated either before or after the hurricanes, it stood at fewer than several thousand by the end of the first week in September 2005. A RAND Corporation study found that, as of December, approximately 91,000 people had returned to their homes, and it was estimated that that number would rise to about 198,000.17 The population has continued to grow, and the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population to be 384,320 in 2014, with somewhat smaller proportions of whites and blacks, more Hispanics and Asians, and fewer children than before the storm.18 New Orleans evacuees were still living in communities throughout the country.

Many homes were destroyed by the floods and many damaged houses remain, especially in the poorer areas of the city that were badly inundated. Housing problems account for some health problems among hurricane survivors. FEMA had supplied trailers for people whose homes had been destroyed, and it later became apparent that the air in these trailers was contaminated with unhealthy levels of formaldehyde. Mold, common in many homes that had been under water during the floods, caused respiratory problems in people with allergies. Wells had been contaminated. Mosquito-borne diseases were a threat, as well as home invasions by rodents and snakes. An estimated 50 percent of survivors are expected to suffer from persistent psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder.19 The full extent of the health consequences of the disaster may never be known.

Principles of Emergency Planning and Preparedness

The evident weaknesses in the response to the 9/11 attacks called attention to the need for advance planning for possible future disasters. After 9/11, the federal government funded planning efforts throughout the nation, but obviously the results were not adequate to be ready for Hurricane Katrina. Two essential ingredients of an emergency plan missing in both New York and New Orleans were coordination and communication. The lack of these functions in New York resulted in part from the fact that the emergency management headquarters and communication antenna were disabled in the event. In New Orleans also, communication was disabled by the loss of electricity and telephones throughout the region. This situation highlights the importance of emergency system redundancy. A backup plan for managing the crisis in the absence of these resources should have been in place in both places. Redundancy in the communication system would have ensured, for example, that critical information about evacuation routes could have been shared with everyone in the World Trade Center towers. In New Orleans, an unambiguous message to evacuate did not come until too close to the time the hurricane struck for it to be acted on by the most vulnerable of the population. The situations were aggravated in New York by a history of competition between police and fire departments and the OEM and in New Orleans by the lack of a competent federal official with whom the governor and mayor could coordinate.

Because any disaster will require a coordinated response from a number of different agencies, the basic principle used in the immediate response to an emergency is the Incident Command System (ICS).20 This approach puts a single person, who has responsibility for managing and coordinating the response, in charge at the scene. Disaster response is generally managed by authorities from local government agencies, because the response must be immediate and local authorities are closest to the scene and know the territory. The lead agency is often the fire department or the police department. The state and federal government provide technical assistance and backup resources.

Agencies involved in the ICS might include an emergency operations center, the fire department, the police department, the emergency medical system, the public health agency, the American Red Cross, the electric company and gas company, and, sometimes, the highway department or, as in the case of the World Trade Center, the Port Authority and the manager of the buildings. Most of these agencies would know their responsibilities in an emergency and would have practiced them as part of their planning and preparedness process. Different agencies might have different communications networks, but it is critically important that all communication be integrated. The public health agency, in coordination with emergency medical services and hospitals, is responsible for directing patients to the appropriate level of care and for dispatching ambulances according to the availability of appropriate resources such as operating rooms and intensive care units. On September 11, one nearby hospital was swamped with “walking wounded” and critical patients, while a trauma center only three miles away sat idle.3 In New Orleans, hospitals and nursing homes lacked plans for evacuating their patients, and governments were not prepared to assist. FEMA has now developed a system called the National Incident Management System (NIMS), which standardizes the organizational structures, processes, and procedures that communities should employ in planning for an emergency. It also provides guidelines and protocols for integration of all levels of government and the voluntary and private sectors in coping with a disaster.21

In a guide to public health management of disasters published by the American Public Health Association, the author lists 12 tasks or problems likely to occur in most disasters.20 All of these tasks depend on effective interorganizational coordination and should be sorted out and practiced ahead of time.

• Sharing information: Two-way radios are often the most reliable way to communicate, but it is important to choose a common frequency.

• Resource management: Personnel should identify themselves at a check-in area and should be given an assignment and a radio; arrival of equipment and supplies should be logged in and they should be distributed where they are most needed.

• Warnings should be issued and evacuations ordered by the appropriate agencies. The warnings should be delivered, usually by the mass media, in a manner that will prompt appropriate action by the population.

• Warnings must be unambiguous and consistent and must include specific information about who is at risk and what actions should be taken.

• Search and rescue operations should be coordinated so that casualties are entered into the emergency medical services system and the healthcare system.

• The mass media should be used to warn the public about health risks after the disaster as an effective public health measure.

• Triage, a method for sorting survivors by severity of their injury and need for treatment, should be established at the scene by trained medical personnel.

• Casualty distribution: Protocols should be established to ensure that patients are distributed among available hospitals or other facilities.

• Tracking of patients and other survivors is difficult but, to the extent it is possible, should be done in order to avert later difficulties.

• Establishing methods to care for patients with all levels of need should be part of the advance planning. Many survivors seek care for minor injuries or may need prescription medications for chronic medical conditions. Backup arrangements should be made for care of patients when hospitals and other healthcare centers are damaged, including backup supplies of power and water and plans to evacuate to alternative sites.

• Management of volunteers and donations should be planned for; resources should be collected, organized, and distributed at a site outside the disaster area to not disrupt ongoing emergency operations.

• Expect the unexpected. Be ready to respond to unanticipated problems.

The plan should be practiced at least once, and preferably once per year. The exercises can be desktop simulations, field exercises, or drills. The time for partners to meet each other is before, not after, the disaster strikes.

After September 11, the federal government has provided substantial resources to states and major metropolitan areas for public health preparedness, including preparedness for natural disasters, bioterrorism, and chemical and radiological disasters. Since 2002, the CDC has invested more than $9 billion in state, local, tribal, and territorial public health departments to upgrade their ability to respond to a range of public health threats.22 The money is used for planning, training, improving communication and coordination, strengthening hospitals and laboratories, and improving epidemiology and disease surveillance in state and local areas. A Strategic National Stockpile includes medical supplies, antibiotics, vaccines, and antidotes for chemical agents. In the event of an emergency, federal personnel can deliver these supplies to the people who need them anywhere in the United States within 12 hours.

An evaluation of the progress made by 12 metropolitan areas between September 11, 2001 and May 2003 found that emergency preparedness had improved, but gaps still remained. The researchers highlighted three communities of different sizes that they found to be especially strong in their level of preparedness: Syracuse, New York; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Orange County, California.23 The success of these three communities is credited in part to previous experience with public health threats. Syracuse, for example, has a nuclear power plant nearby, which had stimulated the population’s concern about a nuclear accident or a terrorist attack. Indianapolis has done extensive planning over the years for the annual Indianapolis 500 auto races and other large sporting events. Orange County has experience in disaster planning because of the ongoing threat of earthquakes and fires; a nuclear power plant is also located nearby. Other factors that contribute to readiness, the researchers concluded, are strong leadership, successful collaboration, and adequate funding.23

Congressional hearings on the response to Hurricane Katrina, however, noted in early 2006 that whatever improvements had been made to our capacity to respond to natural or manmade disaster more than four years after 9/11, U.S. disaster preparedness remained dangerously inadequate. A report by a bipartisan committee of the U.S. House of Representatives identified failures at all levels of government. “All the little pigs built houses of straw,” the report said. “Katrina was a national failure, an abdication of the most solemn obligation to provide for the common welfare.”24 Whether the nation would be better prepared today will not be known until the next emergency.

Bioterrorism Preparedness

The anthrax letters attack of fall 2001 constituted a terrorist attack just as surely as the hijacking and plane crashes, and similarly spread terror in the American population, although it caused few deaths. The anthrax letters were recognized to be a terrorist attack in part because of the heightened alertness created by the events of 9/11, and in part because anthrax is such a rare pathogen in humans. Anthrax had been identified as a possible agent of biowarfare in the planning that the federal government had been carrying out during the late 1990s. If a less conspicuous pathogen had been used, the attack might not have been recognized as quickly. For example, the 1984 Salmonella outbreak in Oregon was not recognized as a deliberate attack until much later, when the cult members quarreled publicly about the attack, and a criminal investigation was launched.25

Bioterrorism requires a very different kind of preparedness strategy than the response needed for dramatic disasters such as a hurricane or the attack on and collapse of the World Trade Center towers. The greatest challenge in bioterrorism preparedness might be the ability to recognize that an attack is underway. Accordingly, the CDC coordinated extensive efforts throughout the nation to improve the public health infrastructure, understanding that the response to a biological attack must be the same as that for a natural disease outbreak. As Dr. Julie Gerberding, then director of the CDC said, “We are building … capacity [to handle biological terrorism] on the foundation of public health, but we are also using the new investments in [combating] terrorism to strengthen the public health foundation” because “these two programs are inextricably linked.”26

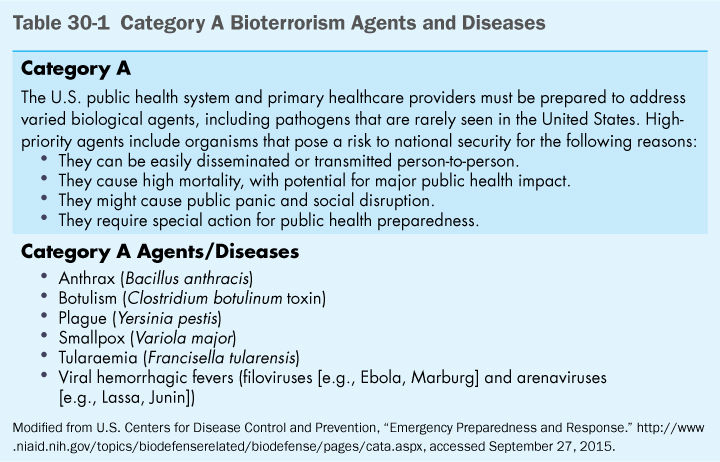

The CDC has listed pathogens most likely to be used in a terrorist attack. Category A agents, shown in (Table 30-1), include smallpox, anthrax, Ebola, and other hemorrhagic fever viruses. These agents can be easily disseminated or transmitted person-to-person and cause high mortality, with potential for major public health impact. Recommendations for preparing for biological attacks are shown in (Table 30-2).

The public health capacities that are being strengthened to improve recognition of a disease outbreak include (1) educating physicians and other medical workers to recognize unusual diseases (unfortunately, the system failed in the case of Thomas Eric Duncan, whose Ebola infection was not suspected by medical workers when he showed up at the emergency room in Texas in 2014, although fortunately, this was not a bioterrorist event);27 (2) monitoring emergency rooms for certain patterns of symptoms; (3) opening new laboratories with the capability of identifying unusual viruses and bacteria; and (4) improving communication between public health agencies at the local, state, and federal level and the professionals and facilities most likely to first encounter affected patients. Surveillance activities include emergency room visits, calls to 911 and poison control centers, and pharmacy records to detect increased use of antibiotics and/or over-the-counter drugs. (One early indication of the 1993 cryptosporidiosis outbreak in Milwaukee was that pharmacies were selling out of medications for diarrhea.) Similar measures are important for recognizing chemical attacks as well, and the CDC coordinates an integrated network of state, local, federal, military, and international public health laboratories that can respond to both bioterrorism and chemical terrorism.28 The U.S. Department of Agriculture is similarly conducting surveillance for animal diseases and other agricultural threats. Animal health is an important component of homeland security, both because of the need to protect the food supply and because many animal diseases are also a threat to humans. Seventy-five percent of emerging infections that have recently been identified in humans originate in animals—for example, bird flu, SARS, hantavirus, mad cow disease, and Escherichia coli O157:H7.28 Computer networks serve to alert public health officials about significant or unusual findings from surveillance data. In addition to public health efforts to improve the ability to recognize a bioterrorist attack and identify the agent, the CDC has taken steps to improve response to the event, including the Strategic National Stockpile, as previously described.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree