This chapter discusses the current educational trajectory in the field of speech-language pathology. It also provides a discussion of emerging trends and finally offers suggestions for consideration with regard to preparation of medical speech-language pathologists (SLPs) for the future. The particular focus of the chapter is on enhancement of the learning experience as individuals move from less advanced (novice) to more advanced (expert) levels of independence. It is reasonable to question the rationale for a chapter on education in a book that focuses primarily on practice-related issues, but the reason is that the educational system in speech-language pathology serves as the backbone and structure for modern practice. Despite the importance of the educational system, our historical and current educational model is highly compartmentalized and uneven, particularly with regard to medical speech-language pathology. While education in the earliest stages (preprofessional) is highly standardized, this high level of calibration dissipates quite rapidly after completion of the master’s degree, with a wide variety of educational and experiential activities that lead to practice in various health settings. Unlike other health disciplines, the trajectory to advanced competence, specialization, and leadership is not well developed in speech-language pathology.

2.2 Historical and Current Perspectives

Speech-language pathology has its roots in both educational and medical disciplines. The formative pathway into practice reflects both of these models. Regardless of the student practitioner’s goal, the influence of both of these pedagogical and practical approaches can be seen in preparation of SLPs today. The current medical speech-language pathology focus sprang from work being done with veterans after World War II, although this work was preceded by discussions that can be traced to a strong European medical influence. The majority of the preparatory work has grown out of schools of psychology, education, and, more recently, health sciences. It is not surprising that the majority of clinical approaches that have developed have focused on behavioral, counseling, and educational techniques (as opposed to surgical or pharmaceutical solutions). Early rehabilitation models used a variety of psychological and educational principles to help those wounded in the war regain functional communication. Much of this early work led to important questions in the study of language and motor speech disorders. Additionally, there has been consistent interest in explanation of underlying physiology and causes of communication disorders that has also led to assessments and treatments that are more physiologically based. The introduction of endoscopic and X-ray examinations, intraoperative brain mapping of language functions, and other such procedures has contributed to utilization and adaptation of tools developed in medicine, usually for other purposes. The integration of the educational and medical models has evolved to a very complex service-delivery model that is unique to speech-language pathology.

Today, most entry-level graduate programs offer students coursework to prepare for practice in both a clinical/medical setting and a school setting. From a practical perspective, the benefits of this “generalist” approach to preparation make great sense. New clinicians graduate with some exposure to the thinking and diagnostic and treatment approaches that are unique to each setting. These new professionals also leave the university understanding the “universals” that cross all of speech-language pathology practice, regardless of the setting. This model has afforded great flexibility to the speech-language pathology workforce over the years, allowing clinicians to have the basic qualifications to move from setting to setting. This approach meets licensure and certification requirements and also ensures that new graduates have a broad range of options as they enter the professional workplace. The model of education is guided by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA; http://www.asha.org/Certification/slp_standards/) Standards for Certification. 1

These standards provide guidance on both preprofessional education requirements (prerequisite knowledge, graduate coursework and practicum, national certification examination) as well as postgraduate clinical fellowship year and maintenance of certification via continuing education requirements. Thus, the key components of education in speech-language pathology include both the preprofessional and postgraduate requirements. The model, though rarely articulated as such, is truly one that requires and encourages career-long learning. The tradition in the profession, however, is to treat these activities as wholly independent from one another, focusing on them as discrete experiences. While great attention has been given to early formative experiences in classroom and clinic, less rigorous attention has been given to the critical nature of the fellowship experience and to the quality of postgraduate continuing education experience in ensuring clinical outcomes, patient safety, and best practice.

2.3 Key Concepts

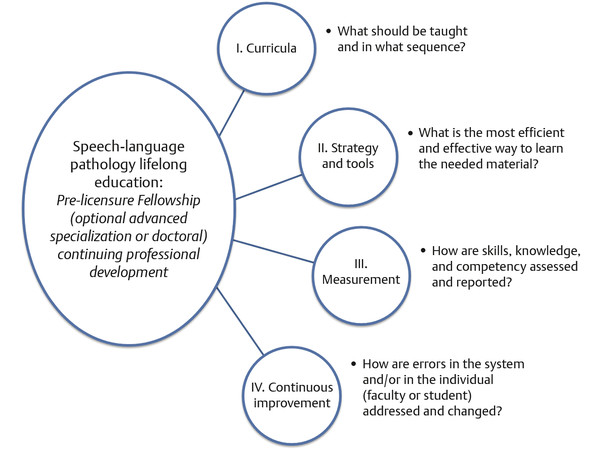

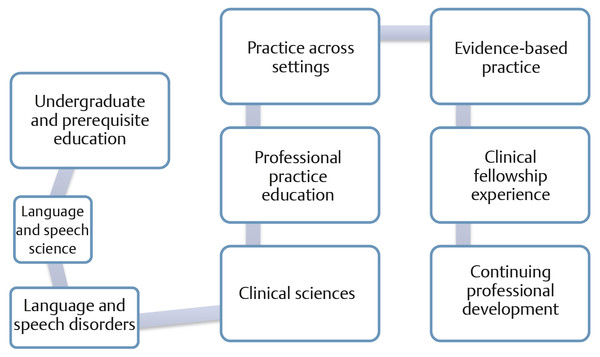

As this chapter unfolds, we hope it is obvious that we feel the divisions across these educational silos are artificial and that continuous attention to the components of good educational strategy applies across the dimensions, although their focus and style will vary according to the learners’ needs. We attempt to capture four elements of instructional consideration that are critical to achievement of good outcomes: curriculum, teaching tools and strategies, measurement of learning, and continuous improvement. We propose that regardless of the level of the learner, the setting where learning is occurring, or the nature of the content being delivered, consideration of these factors improves outcome. These factors apply across the career continuum of each SLP ( ▶ Fig. 2.1). In our view of the educational process, the stages of learning and development for the professional are fluid and adapt to external demands from the specific practice setting, patient-specific needs, and changing trends in the field ( ▶ Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 2.1 Four-factor developmental model of education for speech-language pathology.

Fig. 2.2 The general educational model in speech-language pathology.

2.3.1 Curriculum

The territory of teaching and learning at the graduate level is filled with complexity in subject matter and expectations. Preparing clinicians for a future of integrated service delivery in a wide variety of settings is a daunting task. For purposes of this discussion, it seems safest to reduce this complexity and to increase clarity by posing a number of educational goals as the framework for subsequent discussion. ▶ Table 2.1 provides a set of broad goals that are common in speech-language pathology and other clinical disciplines. These goals span the continuum of professional development from entry-level (graduate) clinical education through postgraduate clinical development in continuing education and/or specialty certification. The goals provide a comprehensive, overarching model for curricular consideration. ▶ Table 2.1 is arranged so that the reader can connect the goal with the specific needs of learners and with guiding questions for the individual instructor. Each level and type of professional education should be guided by these goals and questions, regardless of the stage in development.

Educational goal | Student needs | Instructor’s question |

1. Develop comprehensive understanding of basic subject matter | To understand the underlying physiology of movement in order to assess speech disorders To thoroughly understand early language development in order to treat language impairment in young children | What are the best tools to encourage retention and working knowledge of the material as opposed to memorization? What instructional methods are likely to link underlying principles from the subject matter to clinical decision making? |

2. Establish a clear connection between learned content and real world clinical situations | To appreciate the clinical significance of different disorder types and classifications To select the best treatment approach for a given patient | Are certain types of educational experiences more likely to help learners appreciate the significance of what they are learning in the classroom? |

3. Develop empathy and insight about the impact of communication impairment on an individual patient or family | To demonstrate effective counseling skills To provide support for families and patients as they cope with the disability | How can I help students develop experience in reflection and application of patient-centered thinking? |

4. Provide comprehensive content and exposure across all areas of communication disorders | To expose students to clinical issues in specialized settings that are not readily available in a specific university | What technologies are best for online exposure to a specific setting or patient group? How can I transition my traditional “face-to-face” course to an online or hybrid model of presentation and ensure quality of learning? |

5. Ensure that students are learning and can apply content. | To ensure that students are making reliable clinical judgments about severity of the problem To ensure that learners can choose the right tools to measure a patient’s performance To ensure that learners can use the appropriate treatment for a given patient | Are there good tools to measure student performance beyond pencil and paper exams? How can I construct meaningful (valid) assessments if I am teaching a large class? What are the best assessment models in the clinical setting when I am observing students? |

6. Provide an internship or clinical fellowship experience that leads to the emergence of skills necessary for independent practice at the entry level. | To demonstrate sufficient skills and knowledge for management of a specific clinical population (e.g., aphasia) in a specific setting To demonstrate effective communication, professional practice, and ethical behaviors | What is the best way to design a series of observational and clinical activities to assure a relevant, meaningful and valid experience in the practicum or clinical fellowship setting? How can I measure the competence of the individual learner and provide feedback that is likely to ensure both independence and ongoing professional development? |

7. Establish a procedure to document and ensure a learner’s safe practice and decision making in high-risk situations | To demonstrate best practice:

| What are the preferred methods for developing and documenting competencies for safe practice in a particular clinical area? What is the supervisor’s “teaching” responsibility when an individual learner cannot demonstrate safe practice? |

8. Ensure that a continuing education experience that has been provided is beneficial for the learner and enhances their practice | To demonstrate that a workshop on managing speech and swallowing in patients in the ICU setting has improved clinical skills and knowledge | Are some approaches to continuing education more likely to ensure learning? What are the best ways to measure the outcomes of a professional development experience? |

FEES, fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing | ||

Whether you are an entry-level practitioner, an administrator, a clinician, or a faculty member, these are some of the topics that are in the forefront of most academic discussions about teaching and learning in 21st century speech-language pathology, as well as in other health professions. The growing scope of practice, the expanded knowledge base, the introduction of new topics in the curriculum, and the changing nature of the clients served by SLPs are key internal components that are driving this discussion. Externally, the availability of new technologies, the demand for higher skill levels at entry to practice, greater expectations for independence and critical thinking, and the ever-expanding expectation to control cost of education are equally important. Across higher education, this is a time of great reform both in the organization of education and in its delivery. These points are at the heart of the curricular discussion.

In health professions education, several other specific factors are influencing the educational landscape, including significant demand for collaboration and interprofessional practice, increased competency at the entry level, and increased length and depths of academic programs. Pharmacy, audiology, and physical therapy have joined medicine, psychology, and dentistry as doctoral entry professions. Occupational therapy and nursing both have “optional” advanced professional doctorates, as well as a small number of programs with entry-level doctoral requirements. A similar trend in speech-language pathology is nascent, with only a few advanced clinical/professional doctoral degree programs in place at the time of this writing. In essence, speech-language pathology remains the only major independent health profession without a clear and accessible path to a professional/clinical doctoral degree.

Review of the literature in speech-language pathology education reveals scant discussion of the important tools and pedagogies for professional formation and there is no clearly documented history of our educational methods and approaches. There is considerable discussion of standards of education and content required in the curriculum; however, there has been little public debate or discussion about the best approaches for developing information retention, judgment, or clinical competency. Interestingly there is no significant peer-reviewed journal on education in our discipline. Recently, ASHA Special Interest Group 10 (Higher Education) has initiated an online publication, Perspectives in Higher Education, that does begin to address the need for more published scholarship on teaching and learning in the discipline.

Colleagues in medicine, nursing, and other health professions have all had the benefit of established journals that serve as repositories for discussion, debate, and scholarship around the critical issues of professional formation. For purposes of this chapter, the extant information in the discipline as well as review of information from other health disciplines has been used to organize the discussion around several key topics, including curriculum, course design, emerging tools, evaluation, and outcomes measurement.

The Preprofessional Curriculum

The topic of curriculum has not received extensive discussion in the speech-language pathology literature. It is helpful to think of a curriculum as a set of courses or learning experiences that contribute to a specific level of attainment, which may be a degree (e.g., master’s degree), a certificate (e.g., CCC-SLP), or mastery of a unique clinical capability (e.g., endoscopy). A course or learning experience is one part of an overall curriculum. Thus, in speech-language pathology, the curriculum for the entry-level master’s degree is designed to result in clinical skills and knowledge, as well as overall professional formation, that prepares an individual as a novice practitioner.

Within the context of the overall entry-level curriculum, there are areas of emphasis in medical speech-language pathology. The overall understanding, though rarely explicitly stated, is that the “typical” entry-level clinician has had an exposure to medical speech-language pathology that needs to be deepened and sharpened in the postgraduate clinical fellowship and subsequent continuing education experiences. ▶ Table 2.2 contrasts the curricular emphasis for medical speech-language pathology with the general entry-level curriculum in which it is embedded.

Prerequisite | Professional | Clinical Fellowship | Continuing Education | |

General Preparation |

|

|