Learning Objectives

- Understand the dual relationship between economics and health: how poverty can affect health and how health problems can result in poverty

- Comprehend the possible linkages between wealth and health and how both absolute and relative wealth have an impact on health

- Describe four key mechanisms by which health can affect wealth

- Show the interrelationships between health and economics looking at three key diseases (malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS)

- Outline and describe four key factors in choosing the type of health care financing system

- Outline and describe five major financing methods for health care

- Describe and define risk pooling, risk aversion, adverse selection, and moral hazard

Introduction to Economics and Health

Peter Chirwa is a 4-year-old boy in northern Malawi. His family grows their food on their farm to provide subsistence for the year. When harvests are good, he and his five brothers and sisters eat well throughout the year, but when the harvests are bad, as they have been over the past 3 years, his brothers and sisters become malnourished and sick. Over the past year, two younger siblings died from malnutrition and pneumonia. Unfortunately, Peter’s family is poor and cannot afford to buy food in the market. His family survives on less than 50 cents per person per day, far below the global absolute poverty line of $1. Peter’s uncle lives five houses down. Gaunt and thin and dying from AIDS, he gazes from his bed to his visitors. He has spent all his money trying to buy the lifesaving drugs but can no longer afford the prices. He will probably die in a few months. His family sits by the bedside caring for him, knowing that their future holds nothing but utter destitution. Just down the road, the devastation from poor health can impoverish families and leave them with no income, opportunity, or hope. |

For a long time, it has been recognized that there is a relationship between health and wealth.1 Three possible different pathways may explain this relationship:

Increased wealth leads to health.

Improved health leads to wealth.

The relationship is caused by a third unknown factor.2

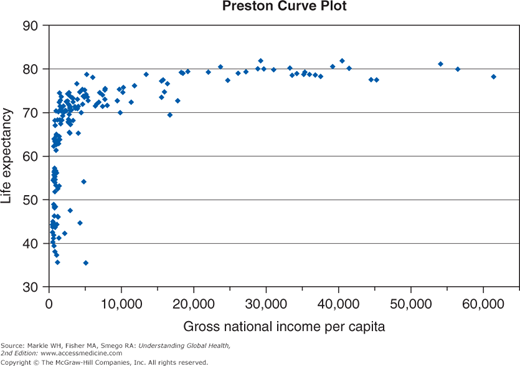

Rising incomes increase government and private spending on goods that directly (e.g., purchasing health care and better nutrition) and indirectly (e.g., better housing, water, and sanitation facilities) improve health3 (see Figure 19-1.)

Figure 19-1.

Health to wealth correlations. The figures provided are for the year 2004 or the latest year for 179 countries. (From World Development Indicators 2006.65) World Bank. World Development Indicators 2006. Washington DC: World Bank, 2006.

In the past decade, there has been increasing recognition that poor health can lead to poverty.4 These interrelationships are linked with political, demographic, and social pressures.

The first part of this chapter analyzes the growing evidence between “wealthier is healthier”5 and the counterclaim “healthier is wealthier.”4

The second part of this chapter focuses on the evidence that the relationship between health systems through their organization, financing, and behavior has an impact on health and economic outcomes. How health systems are financed influences the behaviors of consumers, producers, and intermediaries. It is important to understand how these structures are created, which may in turn have significant impacts on health and economic outcomes.

The Mechanisms from Wealth to Health

In general, wealthier nations are healthier nations. Higher incomes provide the ability to purchase many of the goods and services that promote better health, including more calories and higher quality food products, access to cleaner water, safe sanitation, and higher quality and more complete health services both at a societal and individual level. Furthermore, more wealth can lead to better education and training.

Preston1 noted a strong relationship between health and wealth, and suggested that there is a significant gain in health (as measured by life expectancy) with wealth up to $1,000 per capita. However, Preston noted that after exceeding $1,000 per capita, additional wealth did not lead to significant increases in life expectancy. His classic paper found that between 1940 and 1970, half of the rise in life expectancy was due to improvements in the level of income.

Furthermore, Pritchett and Summers5 in their paper “Wealthier Is Healthier” found that 40% of cross-country differences in mortality can be explained by differences in income growth rates. They estimated a 1% increase in world income would lead to a reduction of 33,000 infant and 55,000 child deaths.

On a countrywide basis at the microeconomic level, Case6 examined the impact of a sudden increase in income from South African old-age pensions on household wealth. She found that the income protected all household members when the old-age pension was put into the overall family income, but when the old-age pension was not put into the family income pot, the income only benefited the individual pensioners. She outlined possible reasons for this advantage to be seen in pooled family incomes, including the ability to purchase more help, better sanitation, improved nutrition, and decreased household psychological stress.

Just as important a finding is that income inequality may lead to poor health. In the Whitehall Study of 10,000 British civil servants, age-adjusted mortality rates were 3.5 times higher for lower grade workers compared with senior administrators.7–9 This suggests that income differentiation of wealth can make a major impact on countrywide health outcomes. A number of other studies support this finding. Wilkinson10 in his study of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, a group of the wealthiest countries in the world, showed that although greater absolute incomes lead to higher life expectancy, greater inequality had a negative impact on average life expectancy. This relative income inequality holds at the individual level, suggesting that people who make lower levels of income than their peers have a worse health outcome.11,12

Wealth can also increase health via indirect mechanisms like education. The World Development Report in 1993, “Investing in Health,” stated that one of the most effective ways to improve health is to provide primary education to young girls.13

The Mechanisms from Health to Wealth

Four major mechanisms link health to increased wealth.14 These four mechanisms are improved productivity, more investment in education (human capital), more investment in physical capital, and utilizing the demographic dividend.

Healthier individuals are more likely to be productive because they are more energetic and less likely to miss work due to illness. Furthermore, healthier families need less time off work to care for ill individuals.

A difficulty in looking at health impacts and its role in affecting productivity is the need to separate out the fixed genetic and socially acquired human capital components to health.15 There is very little to do to change our genetic makeup, leaving us to concentrate on behavioral aspects to improve our health capital.

Strauss16 believed productivity of labor increases when individuals receive more calories. Because increased labor productivity may have had a reverse effect in leading to more food consumption, he used community variation in the price of food as a control variable. A number of subsequent articles have confirmed that nutrition does increase labor productivity.17-19 Strauss and Thomas20 in a later work showed that these effects tend to diminish as the daily intake reaches approximately 2,000 kcal.

Thomas and Strauss21 highlight two key conceptual links from health to productivity relevant to developing countries. First, the impact of predominantly communicable diseases in developing countries affects individuals throughout their lifetimes; noncommunicable diseases in more developed countries predominantly affect the elderly. Second, because developing countries tend to be labor intensive, poor health reduces income disproportionately since a higher percentage of the work force is employed in labor-intensive industries.22 Bhargava et al23 confirmed that higher adult survival rates lead to higher growth rates of income in low-income groups.

Schultz, in a series of papers, looked at the direct impact of health on wages.15,24,25 He found that “an increase in BMI of one unit was associated with a 9% increase in wages for men in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, and a 7% increase in wages for women in Ghana and a 15% increase in Cote d’Ivoire.”15 Similarly, a 1 centimeter gain in height was associated with a 5% increase in wages in Brazil in men and a 7% increase in women.15 Bloom, Canning, and Sevilla22 showed that a 1-year increase in life expectancy at birth results in a 4% increase in economic output. In summary, better health does lead directly to better wages and overall, macroeconomic output.

When looking at the American South at the beginning of the 20th century, Bleakley26 found that the eradication of hookworm led to an improvement in wages by 45%, and half the wage gap difference between the American North and American South was due to disease factors.

A number of economic studies27–29 have shown that longer life expectancy and lower rates of mortality lead to higher incomes and better economic performance.

Similarly, much work has been done to look at the role of maternal health and nutrition as important determinants of future chronic health problems in children, otherwise known as the “Barker hypothesis.”30,31 Poor health does not just have productivity effects in the short term; it may have intergenerational effects that contribute to a country’s long-standing poor labor productivity.

Poor health conditions decrease life expectancy and reduce the amount of human capital investment because individuals have shorter time horizons to regain the costs of the human capital investment. Furthermore, health may directly decrease human capital investments because children may be sick or have less energy to go to school.

Health plays a fundamental role in developing learning capacity. Damages occur in two specific phases:

In utero: During the time the child is inside the mother’s womb, a number of prenatal insults can occur, including poor genetics, alcohol, smoking, drugs, poor nutrition, infections, and hypertension that lead to poor brain development.

Postnatal: A number of problems after birth lead to poor development including, diseases such as meningitis, diarrhea, HIV/AIDS, and pneumonia, and other problems such as head injuries, malnutrition, poor maternal education, inadequate childhood stimulation, and poverty. Any of these insults may lead to poor intellectual development.

Leslie and Jamison32 state that three general educational issues may occur with poor health:

Children may not start school at the typical age.

Children may have poor learning capacity once school starts.

There may be a gross gender imbalance with a decreased number of female children participating in school.

So poor schooling has what implications? Mincer33 showed that an additional year of schooling appears to increase earnings by 10% in the United States and suggested that increasing an average level of schooling should increase economic growth. Bloom, Canning, and Chan34 showed that increasing educational levels may significantly increase sub-Saharan African growth and help Africa escape its poverty trap. In particular, investing in higher education may have a benefit in improving the overall economic growth of Africa.

Therefore, poor health may lead to an underinvestment in health capital and subsequently have a large effect on wages and overall economic development.

Like human capital, short life expectancy will reduce the amount of investment in physical capital because of the reduction in time to recuperate investment costs. However, a consequential advantage of longer life is that individuals need to save for retirement, and hence increase the investment in physical capital with the hope of future return.

Disease has a disproportionate effect on poor rural households. As stated previously, there may be a significant reduction in individual productivity. Second, there may be spending to prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease. Third, Nur35 showed that malaria decreases household savings as families increasingly spend money to hire labor to compensate for productivity losses from individuals infected with malaria. Therefore, there is less money available to invest in physical capital.

Even the threat of ill health may have an enormous impact. For example, severe acute respiratory syndrome was estimated to cost the city of Toronto $1.5 billion in lost tourism and investment in the city, even though it led to only 44 deaths.36

The final mechanism for how health improvements could affect economic growth is through the “demographic dividend.” The theory is that health improvements trigger a decline in mortality rates, followed by a decline in fertility rates years later. This leads to a large population bulge. This group eventually proceeds through productive working years and produces a large working-age population relative to the young and old-age dependent populations. This large working-age to dependent-age population ratio gives a window of opportunity for economic growth but does not guarantee it. It requires appropriate countrywide conditions (stable politics, good macroeconomic policies, openness to trade, and good health status) to maximize the gains.

Bloom and Williamson28 suggest a third to half of the East Asian miracle from 1965 to 1990 can be explained by the demographic dividend. Similarly, Bloom and Canning37 highlight the importance of contraception in reducing fertility and triggering a demographic dividend, leading to the Irish economic boom in the 1980s and 1990s.

Economic Impacts of Three Key Diseases

Malaria, tuberculosis (TB), and HIV/AIDS are examples of diseases that have significant economic impacts on populations.