professionals in infection control and occupational health, prevention specialists, and administrative staff. The goal is to describe how to incorporate economic methods into the design, execution, and evaluation of infection control and occupational health programs.

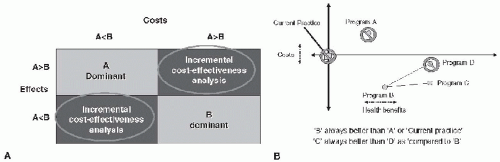

Outputs and costs: In determining if and when to conduct an economic analysis, the comparative outputs (effects) and anticipated cost estimates need to be identified (6,7). The output, potential mediating factors, and costs of the existing (A) program can be compared to the output, mediating factors, and costs of one or more alternative (B) programs (Fig. 96-1). While the most effective program may also have the lowest cost (dominant scenario), it is not necessarily true that the lowest-cost option is the most cost-effective. Consideration must be given to the scenario whereby production of the most units of a given outcome may be impractical to implement, because it is so costly from a supply and demand perspective and it either diverts limited resources from other uses or requires more resources than are available. The cost estimate should include identification of cost factors, data entry methods, calculation of program costs, and determinants of cost saving. If the feasibility assessment of effects and costs are dominant for one program versus the other, it would be plausible to proceed with a simplified cost-minimization or cost-consequence analysis. If instead the feasibility assessment suggests differential effects and costs, the inclusion of an incremental CEA should be explored as an aid to the decision-making process. While the purpose of economic analysis in occupational health typically facilitates an investment in health and safety, the efficiency of this process means that the costs of doing a little more (the marginal cost) to enhance safety equal the benefits (18). Hence, the marginal returns in terms of health and welfare enhancements of the healthcare personnel result from risk reduction (18).

FIGURE 96-1 A: Determining when to conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis for program A versus program B. B: Is more infection control a smart investment?

Principles of economic theory: Economic analysis within healthcare epidemiology is complex given the dynamic algorithms for resource allocation, revenue generation, expenditures, opportunity costs, and assessment of health outcomes in hospitals, alternative care sites, and home-based care. Economic analytical methods are based on a fundamental concept of efficient use of available resources which includes the economics of resource allocation and the efficiency in the use of these resources (19). Analytical difficulties include the estimation of a market price for the resources and the decisions related to allocation of limited resources among seemingly unlimited demands (19). Opportunity cost is relevant to economic evaluations in healthcare epidemiology and represents the value of the resource when it is dedicated in its next best use. Opportunity costs are expressed as the value of lost output if the resource is employed in an alternative productive process (19). Opportunity cost analysis is an important component of business decisions but is not equivalent to a line-item cost in a financial statement. The benefits from the next-best use in resource allocation may be smaller than those of the current use, indicating that the current use is best, or the benefits may be greater, in which case the alternative would be considered preferable (20). Opportunity costs are incorporated into the methodology of CEA.

Practical considerations: Three core questions have been identified as relevant for assessment of HAI (21): Why measure the cost? What outcome should be used to measure the cost? And what is the best method for making the selected cost measure? (21). First, the costs permit objective assessment of the allocated resources. Second, in hospital-based analysis, one cost measure is the number of bed-days saved valued in dollars (21). A health economist may further value bed-days saved as the next best alternative use or the economic opportunity value of the marginal healthcare resources released as a result of fewer HAI (21). Lastly, the selected cost measure is at risk for measurement bias that pertains

to identification of the comparator group as well as time-dependent bias (21,22). After the decision to embark on a robust economic analysis has been made, the relationship between the resources involved in the output (outcome of interest) and the estimate of costs must be considered in more detail. The resources, or inputs, require a unit of measure such as health personnel hours or number of encounters, medical supplies, and diagnostic tests. Measuring this productive process in healthcare epidemiology is especially complicated because the patient is both an input and an output in the process (19). The relationship between inputs and outputs can be extrapolated from an applied understanding of production function (22). A production function focuses on analysis of the relationship between quantities of the input and quantities of output in which the details are often a “black box” (Fig. 96-2). Three major components of the evaluative method are input or resources, mediating factors, and outputs that are goods, services, or outcomes. The mediating factors may influence the relationship between the inputs and outputs involved in the production of health. The cost estimates are typically categorized as direct costs, in dollar expenditures, and indirect or intangible costs, which influence the outcome of interest. Based on supply and demand economics, differentiators within the model are due to efficiency, product choice, and product distribution. Efficiency involves the obtainment of maximum output from productive inputs. Product choice includes determining what goods and services should be produced to meet the demands, and product distribution involves who gets the products produced (19,23). For infection control and occupational health programs, different combinations of inputs can produce the same level of output. Hence, substitution analysis of inputs may identify cost saving and opportunity costs, and several analytical techniques exist for the economic analysis of healthcare programs and evidence-based medical care (24,25).

FIGURE 96-2 Production function. (Redrawn from Morris S, Devlin N, Parkin D. Economic analysis in health care. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2007.) |

Type of institution: As the site of an episode of healthcare becomes a continuum from the acute to alternative care settings, measurement of risks and resource allocations become more complicated for infection control or occupational health programs.

Acute care institution: Resource allocations for healthcare epidemiology programs are often determined by hospital size (licensed bed number). In general, infection control budgets include supplies, overhead, and the salaries of staff such as a part-time physician, nurse, secretary, and data programmer. Based on a program budget, outcomes and economic analysis contribute to justification of the return on investment, if not break-even point, for a healthcare epidemiology program (26,27).

Long-term care facilities: Over 1.5 million persons annually reside in US long-term care facilities and the estimated number of infection preventionists per nursing home is fourfold lower than the estimate for infection preventionists in hospital-based care (28). Guidelines exist for prevention and control of infections in long-term care, with endorsement to specifically reduce HAIs (29).

Home care and other alternative settings: The role of infection control in home care is often collapsed into the general responsibilities and resources available to nurses within the individual home care organization. Identified unmet needs for infection control in home care settings are the development of valid definitions for home care-acquired infection and practical methods of surveillance (30). Once established, estimates of incidence and risks can be determined in order to characterize effective interventions (30).

Endemic versus epidemic infection control strategies: As the majority of healthcare epidemiology efforts are dedicated to the control of endemic infections, rather than epidemic infections, resource allocations should parallel this distribution of activity. In infection control programs, CEA needs to distinguish between endemic and epidemic infection control strategies and aim to identify estimates of economic burden incurred from the societal perspective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend four key components for infection control programs targeted to control the spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens: surveillance, applied research, prevention and control strategies, and development or expansion of infrastructure (31). Infection control programs that target prevention and control of spread of multidrug-resistant pathogens should ideally take these components into consideration for CEA.

Surveillance: The degree of pathogen surveillance within a healthcare setting can range from none to that of intense specimen procurement, reporting, and evaluation during an epidemic. The surveillance plan may vary, contingent on the identified pathogen, intervention, and goals of the program. For healthcare systems dedicated to the prevention and control of the spread of multidrug-resistant microorganisms, the options for surveillance span from a threshold alert on clinical isolates to the use of a suppressed or routine passive surveillance system to the incorporation of more elaborate programs with formalized active surveillance.

Applied research: To adequately assess the impact of infection control programs by CEA, resource

allocation is needed for integration of molecular epidemiology methods such as molecular diagnostics of clinical specimens, data programming, and analysis from one or more information systems.

Prevention and control strategies: The strategies employed in healthcare epidemiology and infection control programs are myriad. Such strategies may be categorized as environmental, educational, behavioral, and pharmacologic.

Development or expansion of existing infrastructure: Secure, dynamic infrastructure is crucial for an effective healthcare epidemiology or infection control program. The infection control specialists in large and small programs need access to administrative leadership, database management support, performance monitoring systems, and ongoing educational programs. As a program or hospital department, infection control programs are accountable for patients, healthcare workers, and the public health components of assigned environments. During times of accreditation, healthcare personnel are expected to report on performance and update policies and procedures for the Joint Commission, Health Care Financing Administration, and other federal and state regulatory agencies.

Interventions: Infection control interventions that are best as candidates for widespread implementation are those that are readily modifiable and feasible. Primary prevention interventions involve strategies to reduce risk factors or prevent exposure. Interventions in secondary prevention reduce the effects of the risk or exposure. Treatment interventions treat the insult resulting from the risk or exposure. In occupational health programs for healthcare personnel, the worksite provides an opportunity to promote and sustain healthy behaviors related to diet and exercise (32). Uptake of immunizations by intensive care unit personnel was associated with education and a committed occupational health team in at least one resource-limited setting (33).

TABLE 96-1 Five Types of Economic Analyses for Healthcare Interventions and Programs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cost-minimization analysis: A cost-minimization analysis includes the incremental costs of alternatives that achieve the same outcome. Competing interventions are the same, the only input is cost, and the aim is to decide the least costly way of achieving the same outcome. This simple cost analysis method entails a balance of risk and costs to optimize clinical operations (34).

Cost-consequence analysis: A cost-consequence analysis considers the incremental costs and effects that achieve the same outcome, without an attempt to aggregate the costs and effects (35).

Cost-benefit analysis: As an analytical tool, CBA estimates the net societal benefit of a program or intervention and is measured as the incremental benefit of the program minus the incremental cost, with all benefits and costs measured in dollars (16). The goals in using a CBA are to eliminate procedures when the cost outweighs the benefit and to facilitate or encourage implementation of the procedure when the benefit outweighs the cost (36). The methods include the estimates of costs and benefits and there is a clear decision rule to undertake an intervention if the monetary value of its benefits exceed

its costs. The two major limitations of this method are determining the level at which the benefit is significant enough to implement the intervention and its lack of a societal perspective (36,37).

Estimations of cost: Estimations of cost for HAI require that the incremental costs associated with diagnosing and treating the infection be distinguished from the costs attributable to diagnosis and management of the primary medical problem. Incremental costs of HAI include costs allocated for laboratory, pharmacy, procedures, and additional hospital days. Haley et al. (38) reported in 1981 that approximately half of the additional costs of treating such infections were accounted for by extra days of hospital stay. Several methods for estimating costs by estimating incremental excess length of stay resulting from HAI have been identified: unmatched group comparison, matched group comparison, implicit physician assessment, and an appropriateness evaluation protocol method (39,40).

Unmatched group comparison: In this comparative approach to HAI, the total number of hospital days attributable to HAI is determined by comparing patients with and without HAI. There are no adjustments for severity of illness, and hence this method consistently overestimates additional incremental costs of HAI (41).

Matched control comparison: For assessment of HAI using this method, patients with HAI are matched to uninfected patients who have comparable age, severity of illness, and underlying disease (42,43,44,45 and 46). Alternatively, sites of care can be matched as part of the study design and evaluation (47). These studies are likely to give the most accurate assessment of the additional incremental costs of the HAI (44,45).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree