26 Ear, nose and throat surgery

Ear

Anatomy

External ear

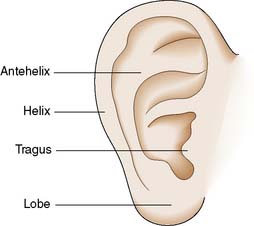

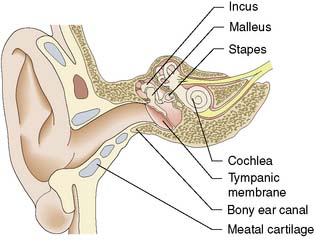

The pinna (Fig. 26.1) is made of fibroelastic cartilage. The external auditory meatus has an outer cartilage portion; the inner part is formed by the tympanic bone (Fig. 26.2). It is lined by squamous epithelium and contains ceruminous glands that produce wax. There is very little subcutaneous tissue and soft tissue swelling is very painful.

Middle ear

The vibrating tympanic membrane is conical and attached to the margin of the bony ear canal laterally and to the handle of the malleus, the first of the three ossicles, medially (Fig. 26.2). The head of the malleus is attached to the body of the incus in the space superior to the middle ear known as the attic. The long process of the incus attaches to the head of the stapes via its lenticular process. The stapes is joined to the oval window margin by the annular ligament. The middle ear is lined by simple cuboidal epithelium containing some mucus-secreting cells. The middle ear space is connected to the nasopharynx by the Eustachian tube, which maintains the middle ear at atmospheric pressure.

Physiology

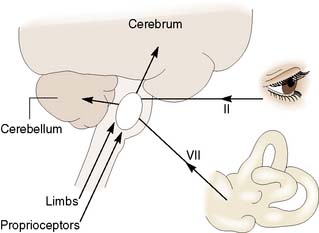

The pinna funnels sound into the ear canal. The tympanic membrane lever mechanism, the ossicular lever mechanism and the large size of the drum relative to the stapes footplate act as an impedance-matching transformer. Vibrations in air are thus transferred to the cochlear fluids without excessive loss of energy. The cochlea converts these endolymph vibrations into electrical impulses in the auditory nerve, by stimulation of hair cells in the organ of Corti. The maximum response to high frequencies occurs in the basal turn of the cochlea. Low frequencies maximally stimulate the apex. Auditory neurons connect via the brainstem to the auditory cortex, where again different groups of cells are stimulated by nerve impulses coded for different frequencies. The hair cells in the ampullae of the semicircular canals are stimulated by angular acceleration. The saccule and utricle are stimulated by linear acceleration. Information from the labyrinths, eyes and limbs is combined within the brainstem. Connections from the vestibular nuclei pass to the cortex and the cerebellum (Fig. 26.3).

Assessment

Clinical features

Disorders of the external or middle ear can impair sound transmission to the inner ear and cause conductive deafness. Sensorineural deafness results from lesions of the cochlea or its nerve. Deafness is often associated with a noise in the ear (tinnitus). Ear pain (otalgia) may be due to ear disease but may also be referred from other sites (Table 26.1). Ear-related disorders of balance usually cause a sensation of movement (vertigo), most often rotation. ‘Unsteadiness’ however, typically has a non-otological cause. Patients with ear disease occasionally fall to the ground but never lose consciousness.

Table 26.1 Causes of referred otalgia

| Pharynx and larynx |

| Mouth |

| Temporomandibular joints (TMJ) |

| Neck |

| Paranasal sinuses |

Audiometry

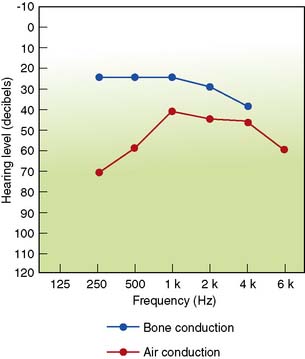

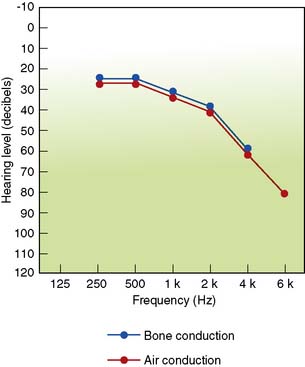

Hearing by air conduction can be assessed by pure tone audiometry, in which sounds of known pitch and loudness are presented to each ear in turn via headphones. Bone conduction (cochlear function) can be separately tested by applying sounds to the mastoid process. A masking tone is needed if the two cochleae are to be tested separately. The difference between the air and bone conduction gives the level of conductive hearing loss (Figures 26.4 and 26.5). The patient’s ability to hear speech can be tested by presenting lists of words via headphones. The percentage correctly identified at different loudness levels allows derivation of a speech reception threshold (50% of words correct) and a discrimination score. Middle ear function (compliance) can be assessed by tympanometry. The amount of sound from a probe reflected back from the drum is measured while the pressure in the ear canal is made to vary. The compliance is maximal when the pressure in the ear canal equals the pressure in the middle ear, because when pressure is the same on both sides of the drum it is maximally mobile. Tympanometry is most often used to confirm the presence of fluid in the middle ear.

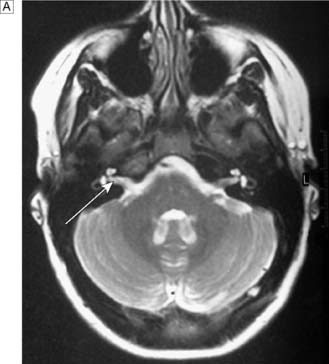

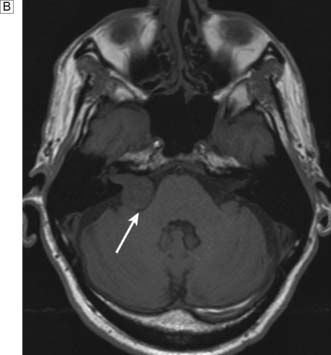

Temporal bone imaging

In patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, MRI is used to detect an acoustic neuroma (Fig. 26.6). MRI also demonstrates the presence of normal fluid in the cochlea before attempting cochlear implantation. CT scans can be used to demonstrate temporal bone anatomy, congenital abnormalities and fractures or unusual pathology.

Diseases of the pinna

Bat ears

A developmental abnormality results in absence of the antihelical fold (see Fig. 26.1). This produces prominent ears that cause embarrassment. The abnormality can be corrected surgically.

Diseases of the middle ear

Acute suppurative otitis media

This is a bacterial infection of the middle ear space, usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae, most commonly occurring in young children (3 years of age and under). Children present with a combination of ear pain (otalgia), fever and malaise. On examination, dilated blood vessels are seen on the drum surface in the early stages. The drum then becomes red and begins to bulge. Perforation with discharge frequently occurs, usually followed by spontaneous healing. Antibiotic therapy remains controversial: the majority of cases resolve spontaneously in a few days (EBM 26.1). Antibiotics are useful in high risk patients (e.g. immunosuppression) as they shorten the episodes and reduce the rate of infective complications such as mastoiditis, facial palsy or meningitis.

Otitis media with effusion (OME), or ‘glue ear’

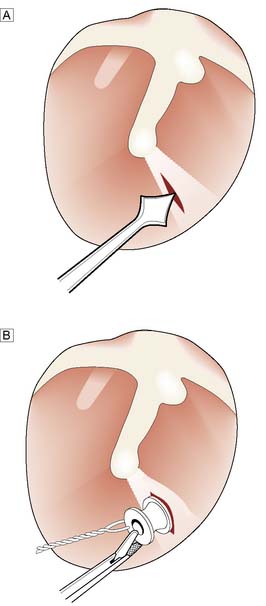

In this condition, fluid accumulates in the middle ear space, usually in children. A minority of adult cases are caused by nasopharyngeal tumours and systemic disease. Childhood OME causes hearing loss and may interfere with the acquisition of language and performance at school. Virtually all cases resolve spontaneously, but this may take as long as 10 years. Initial management involves documentation of the presence of effusion and the degree of hearing loss during a period of watchful waiting. If the effusions persist, hearing may be improved by drainage of the effusion (myringotomy) and insertion of a ventilation tube (Fig. 26.8). In children, removal of the adenoids leads to more effective resolution. Spontaneous resolution may also occur in adults, but often effusions persist. Ventilation tubes can also be of value, but some cases are better managed with a hearing aid.

Chronic suppurative otitis media

This causes aural discharge and deafness.

Atticoantral or squamous disease

Summary Box 26.1 Otitis media

• Acute otitis media is extremely common under the age of 3 years

• The child typically awakes crying at night with a painful ear. The diagnosis is confirmed by a red, inflamed bulging tympanic membrane on otoscopy

• Pain relief is important. Antibiotics should be given to prevent the development of complications

• Otitis media with effusion (glue ear) occurs transiently in many children and is manifested by temporary hearing impairment. Most cases settle spontaneously. Bilateral persistent hearing impairment may demand surgery (adenoidectomy, or insertion of a grommet)

• Chronic otitis media involves the middle ear and mastoid mucosa. There is permanent perforation of the tympanic membrane, hearing loss and a mucopurulent discharge. Inactive ears require closure of the perforated membrane (myringoplasty) and rebuilding of the ossicular chain. Ears with cholesteatoma may require surgical removal of the posterior canal wall to open the attic or mastoid cavity and so reduce the risk of meningitis, intracranial abscess and facial palsy.

Diseases of the inner ear

Deafness

Deafness is most commonly due to changes in the cochlea. Ageing produces a gradual deterioration in hearing acuity (presbycusis). The cochlea may be damaged by chronic noise exposure, blast injuries and temporal bone fractures. Significant noise exposure may occur in heavy industry and agriculture, from playing in rock bands and shooting. Deafness may also be inherited or a manifestation of systemic disease. Some drugs, such as aminoglycosides and cytotoxic agents like cisplatinum, can damage the cochlea. Viral infections such as mumps and rubella can also cause sensorineural deafness. Unilateral hearing loss occurs in acoustic neuroma (Fig. 26.6B).

Nose

Anatomy

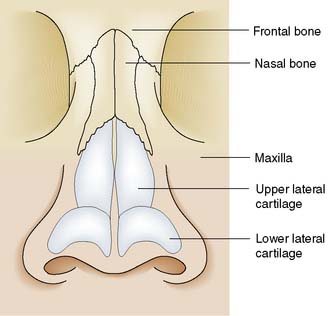

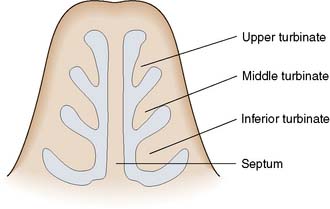

The nasal skeleton consists of two nasal bones superiorly and two pairs of cartilages inferiorly (Fig. 26.9). The nasal cavity is divided in two by a partition composed of cartilage anteriorly and bone posteriorly (the nasal septum). Three turbinate bones protrude from the lateral wall of the nose (Fig. 26.10). Between the inferior and middle turbinates is the middle meatus of the nose. Most of the paranasal sinuses open into this area under cover of a soft tissue flap known as the uncinate process. Obstruction of the sinus ostia in this area can cause sinus pain and may lead to sinus infection. Superior to the superior turbinate is an area of olfactory epithelium from which arise the nerve fibres of the olfactory nerve. The anterior portion of the nasal septum is called Little’s area. Here prominent veins are often found, and nose bleeds most often arise from this part of the nose.

Assessment

Imaging

Imaging is not required if nasendoscopy is normal. Images are useful preoperatively to give the surgeon a guide as to individual variations especially in the areas of potential hazard – orbital wall, floor of the anterior cranial fossa (skull base) and to minimize the risk of complications. Computed tomography (CT) is the best means of imaging the paranasal sinuses and also gives information about the middle meatus of the nose, where the sinus ostia are situated (Fig. 26.11). The sinuses can also be visualized by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but the bony anatomy is not shown and mucosal disease is exaggerated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree