E

Earache

[Otalgia]

Earaches usually result from disorders of the external and middle ear associated with infection, obstruction, or trauma. Their severity ranges from a feeling of fullness or blockage to deep, boring pain. At times, it may be difficult to determine the precise location of the earache. Earaches can be intermittent or continuous and may develop suddenly or gradually.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask the patient to characterize his earache. How long has he had it? Is it intermittent or continuous? Is it painful or slightly annoying? Can he localize the site of the pain? Does he have pain in any other areas, such as the jaw?

Ask about recent ear injury or other trauma. Does swimming or showering trigger ear discomfort? Is discomfort associated with itching? If so, find out where the itching is most intense and when it began. Ask about ear drainage and, if present, have the patient characterize it. Does he hear ringing, “swishing,” or other noises in his ears? Ask about dizziness or vertigo. Does it worsen when the patient changes position? Does he have difficulty swallowing, hoarseness, neck pain, or pain when he opens his mouth?

Find out if the patient has recently had a head cold or problems with his eyes, mouth, teeth, jaws, sinuses, or throat. Disorders in these areas may refer pain to the ear along the cranial nerves.

Finally, find out if the patient has recently flown, been to a high-altitude location, or been scuba diving.

Begin your physical examination by inspecting the external ear for redness, drainage, swelling, or deformity. Then apply pressure to the mastoid process and tragus to elicit any tenderness. Using an otoscope, examine the external auditory canal for lesions, bleeding or discharge, impacted cerumen, foreign bodies, tenderness, or swelling. Examine the tympanic membrane: Is it intact? Is it pearly gray (normal)? Look for tympanic membrane landmarks: the cone of light, umbo, pars tensa, and the handle and short process of the malleus. (See Using an otoscope correctly.) Perform the watch tick, whispered voice, Rinne, and Weber’s tests to assess for hearing loss.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Abscess (extradural). Severe earache accompanied by a persistent ipsilateral headache, malaise, and recurrent mild fever characterizes this serious complication of middle ear infection.

♦ Barotrauma (acute). Earache associated with barotrauma ranges from mild pressure to severe pain. Tympanic membrane ecchymosis or bleeding into the tympanic cavity may occur, producing a blue drumhead; the eardrum usually isn’t perforated.

♦ Cerumen impaction. Impacted cerumen (earwax) may cause a sensation of blockage or fullness in the ear. Additional features include

partial hearing loss, itching and, possibly, dizziness.

partial hearing loss, itching and, possibly, dizziness.

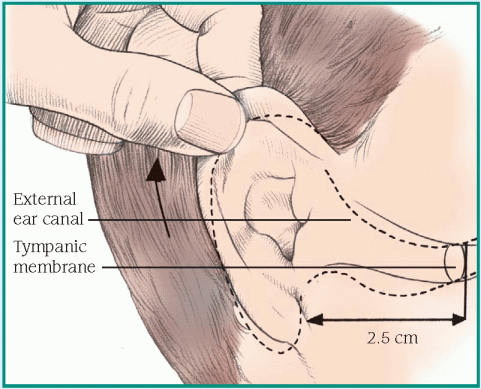

When the patient reports an earache, use an otoscope to inspect ear structures closely. Follow these techniques to obtain the best view and ensure patient safety.

Child younger than age 3

To inspect an infant’s or a young child’s ear, grasp the lower part of the auricle and pull it down and back to straighten the upward S curve of the external canal. Then gently insert the speculum no more than ½″ (1.2 cm) into the canal.

|

♦ Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica. Chondrodermatitis nodularis chronica produces small, painful, indurated areas along the auricle’s upper rim.

♦ Ear canal obstruction by an insect. An insect lodged in the ear canal may cause severe pain and distressing noise.

♦ Frostbite. Prolonged exposure to cold may cause burning or tingling pain in the ear, followed by numbness. The ear appears mottled and gray or white; it turns purplish blue as it’s warmed.

♦ Furunculosis. Infected hair follicles in the outer ear canal may produce severe, localized ear pain associated with a pus-filled furuncle (boil). The pain is aggravated by jaw movement and relieved by rupture or incision of the furuncle. Pinna tenderness, swelling of the auditory meatus, partial hearing loss, and a feeling of fullness in the ear canal may also occur.

♦ Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Herpes zoster oticus causes burning or stabbing ear pain that’s commonly associated with ear vesicles. The patient also complains of hearing loss and vertigo. Associated signs and symptoms include transient ipsilateral facial

paralysis, partial loss of taste, tongue vesicles, and nausea and vomiting.

paralysis, partial loss of taste, tongue vesicles, and nausea and vomiting.

♦ Keratosis obturans. Mild ear pain, otorrhea, and tinnitus are common in keratosis obturans. Inspection reveals a white glistening plug obstructing the external meatus.

♦ Mastoiditis (acute). Mastoiditis causes a dull ache behind the ear accompanied by lowgrade fever (99° F to 100° F [37.2° C to 37.8° C]). The eardrum appears dull and edematous and may perforate, and soft tissue near the eardrum may sag. A purulent discharge is seen in the external canal.

♦ Ménière’s disease. Ménière’s disease is an inner ear disorder that can produce a sensation of fullness in the affected ear. Its classic effects, however, include severe vertigo, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss. The patient may also experience nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, and nystagmus.

♦ Middle ear tumor. Deep, boring ear pain and facial paralysis are late signs of a malignant tumor.

♦ Myringitis bullosa. Myringitis bullosa is a rare bacterial infection that causes sudden, severe ear pain that radiates over the mastoid and lasts for up to 48 hours. Small serous or blood-filled vesicles may dot the reddened tympanic membrane. Transient hearing loss and a serosanguineous discharge may also occur.

♦ Otitis externa. Earache characterizes both acute and malignant otitis externa. Acute otitis externa begins with mild to moderate ear pain that occurs with tragus manipulation. The pain may be accompanied by low-grade fever, sticky yellow or purulent ear discharge, partial hearing loss, and a feeling of blockage. Later, ear pain intensifies, causing the entire side of the head to ache and throb. Fever may reach 104° F (40° C). Examination reveals swelling of the tragus, external meatus, and external canal; eardrum erythema; and lymphadenopathy. The patient also complains of dizziness and malaise.

Malignant otitis externa causes sudden ear pain that’s aggravated by moving the auricle or tragus. The pain is accompanied by intense itching, purulent ear discharge, fever, parotid gland swelling, and trismus. Examination reveals a swollen external canal with exposed cartilage and temporal bone. Cranial nerve palsy may occur.

♦ Otitis media (acute). Otitis media is a middle ear inflammation that can be serous or suppurative. Acute serous otitis media may cause a feeling of fullness in the ear, hearing loss, and a vague sensation of top-heaviness. The eardrum may be slightly retracted, amber colored, and marked by air bubbles and a meniscus, or it may be blue-black from hemorrhage.

Acute suppurative otitis media is characterized by severe deep, throbbing ear pain; hearing loss; and fever that may reach 102° F (38.9° C). The pain increases steadily over several hours or days and may be aggravated by pressure on the mastoid antrum. Perforation of the eardrum is possible. Before rupture, the eardrum appears bulging and fiery red. Rupture causes purulent drainage and relieves the pain.

Chronic otitis media usually isn’t painful except during exacerbations. Persistent pain and discharge from the ear suggest cancer or osteomyelitis of the skull base.

♦ Perichondritis. Perichondritis can cause ear pain accompanied by warmth and tenderness in the outer ear and a reddened, doughlike auricle.

♦ Petrositis. The result of acute otitis media, this infection produces deep ear pain with headache and pain behind the eye. Other findings are diplopia, loss of lateral gaze, vomiting, sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo and, possibly, nuchal rigidity.

♦ Temporomandibular joint infection. Typically unilateral, temporomandibular joint infection produces ear pain that’s referred from the jaw joint. The pain is aggravated by pressure on the joint with jaw movement; it commonly radiates to the temporal area or the entire side of the head.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Administer an analgesic, and apply heat to relieve discomfort. Instill eardrops if necessary. Teach the patient how to instill drops if they’re prescribed for home use.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Common causes of earache in children are acute otitis media and insertion of foreign bodies that become lodged or infected. Be alert for nonverbal clues to earache in a young child, such as crying or ear tugging.

To examine the child’s ears, place him in a supine position with his arms extended and held securely by his parent. Then hold the otoscope with the handle pointing toward the top of the child’s head, and brace it against him using one or two fingers. Because an ear examination may upset the child with an earache, save it for the end of your physical examination.

Edema, generalized

A common sign in severely ill patients, generalized edema is the excessive accumulation of interstitial fluid throughout the body. Its severity varies widely; slight edema may be difficult to detect, especially if the patient is obese, whereas massive edema is immediately apparent.

Generalized edema is typically chronic and progressive. It may result from cardiac, renal, endocrine, or hepatic disorders as well as from severe burns, malnutrition, or the effects of certain drugs and treatments.

Common factors responsible for edema are hypoalbuminemia and excess sodium ingestion or retention, both of which influence plasma osmotic pressure. (See Understanding fluid balance, page 258.) Cyclic edema associated with increased aldosterone secretion may occur in premenopausal women.

Quickly determine the location and severity of edema, including the degree of pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or nonpitting? page 259.) If the patient has severe edema, promptly take his vital signs, and check for jugular vein distention and cyanotic lips. Auscultate the lungs and heart. Be alert for signs of heart failure or pulmonary congestion, such as crackles, muffled heart sounds, or ventricular gallop. Unless the patient is hypotensive, place him in Fowler’s position to promote lung expansion. Prepare to administer oxygen and an I.V. diuretic. Have emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

Quickly determine the location and severity of edema, including the degree of pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or nonpitting? page 259.) If the patient has severe edema, promptly take his vital signs, and check for jugular vein distention and cyanotic lips. Auscultate the lungs and heart. Be alert for signs of heart failure or pulmonary congestion, such as crackles, muffled heart sounds, or ventricular gallop. Unless the patient is hypotensive, place him in Fowler’s position to promote lung expansion. Prepare to administer oxygen and an I.V. diuretic. Have emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a complete medical history. First, note when the edema began. Is the edema worse in the morning or at the end of the day? Is it accompanied by shortness of breath or pain in the arms or legs? Find out how much weight the patient has gained. Has his urine output changed in quantity or quality? Is the edema generalized or localized, dependent or nondependent?

Next, ask about previous burns or cardiac, renal, hepatic, endocrine, or GI disorders. Have the patient describe his diet so you can determine whether he suffers from protein malnutrition. Explore his drug history, and note recent I.V. therapy.

Begin the physical examination by comparing the patient’s arms and legs for symmetrical edema. Also, note ecchymoses and cyanosis. Assess the back, sacrum, and hips of the bedridden patient for dependent edema. Palpate peripheral pulses, noting whether hands and feet feel cold. Finally, perform a complete cardiac and respiratory assessment.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Angioneurotic edema or angioedema. Recurrent attacks of acute, painless, nonpitting edema involving the skin and mucous membranes —especially those of the respiratory tract, face, neck, lips, larynx, hands, feet, genitalia, or viscera—may be the result of a food or drug allergy or emotional stress, or they may be hereditary. Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea accompany visceral edema; dyspnea and stridor accompany life-threatening laryngeal edema.

♦ Burns. Edema and associated tissue damage vary with the severity of the burn. Severe generalized edema (4+) may occur within 2 days of a major burn; localized edema may occur with a less severe burn.

♦ Cirrhosis. A late sign of chronic cirrhosis, edema usually starts in the legs and thighs and may progress to anasarca. Accompanying signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, hepatomegaly, ascites, jaundice, pruritus, bleeding tendencies, musty breath, lethargy, mental changes, and asterixis.

♦ Heart failure. Severe, generalized pitting edema—occasionally anasarca—may follow leg edema late in heart failure. The edema may improve with exercise or elevation of the limbs and is typically worse at the end of the day. Among other classic late findings are hemoptysis, cyanosis, marked hepatomegaly, clubbing, crackles, and a ventricular gallop. Typically, the patient has tachypnea, palpitations, hypotension, weight gain despite anorexia, nausea, slowed mental response, diaphoresis, and pallor. Dyspnea, orthopnea, tachycardia, and fatigue typify left-sided heart failure; jugular vein distention, hepatomegaly, and peripheral edema typify right-sided heart failure.

♦ Malnutrition. Anasarca in this disorder may mask dramatic muscle wasting. Malnutrition also typically causes muscle weakness; lethargy; anorexia; diarrhea; apathy; dry, wrinkled skin; and signs of anemia, such as dizziness and pallor.

♦ Myxedema. In this severe form of hypothyroidism, generalized nonpitting edema is accompanied by dry, flaky, inelastic, waxy, pale skin; a puffy face; and an upper eyelid droop. Observation also reveals masklike facies, hair

loss or coarsening, and psychomotor slowing. Associated findings include hoarseness, weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, bradycardia, hypoventilation, constipation, abdominal distention, menorrhagia, impotence, and infertility.

loss or coarsening, and psychomotor slowing. Associated findings include hoarseness, weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, bradycardia, hypoventilation, constipation, abdominal distention, menorrhagia, impotence, and infertility.

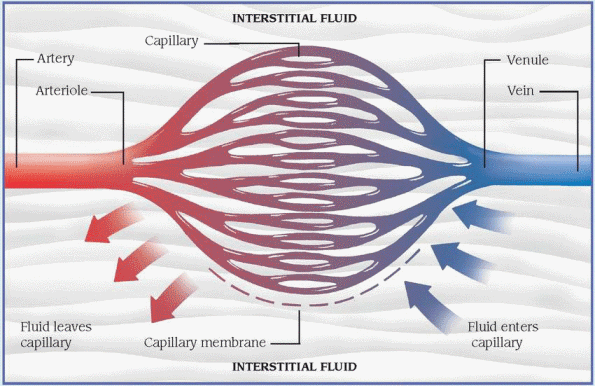

Understanding fluid balance

Normally, fluid moves freely between the interstitial and intravascular spaces to maintain homeostasis. Four basic types of pressure control fluid shifts across the capillary membrane that separates these spaces:

♦ capillary hydrostatic pressure (the internal fluid pressure on the capillary membrane)

♦ interstitial fluid pressure (the external fluid pressure on the capillary membrane)

♦ osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration within the capillary)

♦ interstitial osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration outside the capillary).

|

Here’s how these pressures maintain homeostasis. Normally, capillary hydrostatic pressure is greater than plasma osmotic pressure at the capillary’s arterial end, forcing fluid out of the capillary. At the capillary’s venous end, the reverse is true: The plasma osmotic pressure is greater than the capillary hydrostatic pressure, drawing fluid into the capillary. Normally, the lymphatic system transports excess interstitial fluid back to the intravascular space.

Edema results when this balance is upset by increased capillary permeability, lymphatic obstruction, persistently increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, decreased plasma osmotic or interstitial fluid pressure, or dilation of precapillary sphincters.

♦ Nephrotic syndrome. Although nephrotic syndrome is characterized by generalized pitting edema, the edema is initially localized around the eyes. Anasarca develops in severe cases, increasing body weight by up to 50%. Other common signs and symptoms are ascites, anorexia, fatigue, malaise, depression, and pallor.

♦ Pericardial effusion. In pericardial effusion, generalized pitting edema may be most prominent in the arms and legs. It may be accompanied by chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, a nonproductive cough, pericardial friction rub, jugular vein distention, dysphagia, and fever.

♦ Pericarditis (chronic constructive). Like right-sided heart failure, this disorder usually begins with pitting edema of the arms and legs that may progress to generalized edema. Other signs and symptoms include ascites, Kussmaul’s sign, dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, abdominal distention, and hepatomegaly.

♦ Protein-losing enteropathy. Increased albumin levels lead to progressive generalized pitting edema in this disorder. The patient may

also have a mild fever and abdominal pain with bloody diarrhea and steatorrhea.

also have a mild fever and abdominal pain with bloody diarrhea and steatorrhea.

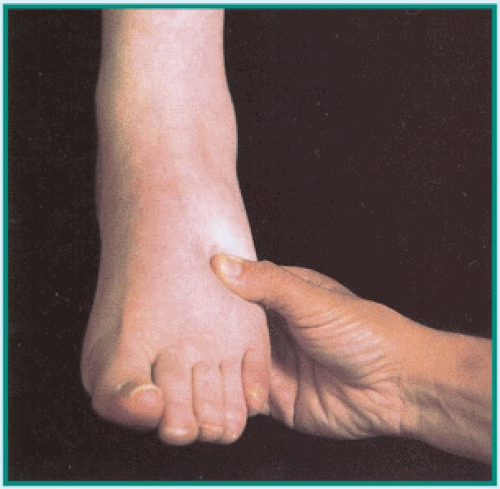

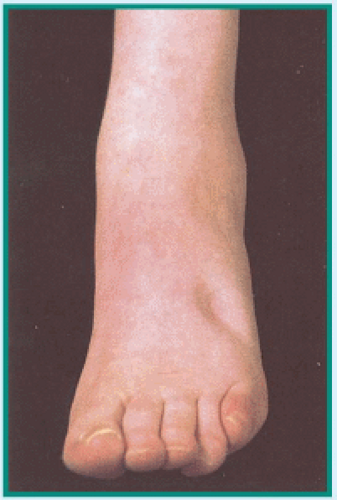

To differentiate pitting from nonpitting edema, press your finger against a swollen area for 5 seconds, and then quickly remove it.

In pitting edema, pressure forces fluid into the underlying tissues, causing an indentation that fills slowly. To determine the severity of pitting edema, estimate the indentation’s depth in centimeters:

1+ (1 cm), 2+ (2 cm),

3+ (3 cm), or 4+ (4 cm).

In nonpitting edema, pressure leaves no indentation because fluid has coagulated in the tissues. Typically, the skin feels unusually tight and firm.

♦ Renal failure. Generalized pitting edema is a late sign of acute renal failure. In chronic failure, edema is less likely to become generalized; its severity depends on the degree of fluid overload. Both forms of renal failure cause oliguria, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, hypertension, dyspnea, crackles, dizziness, and pallor.

♦ Septic shock. A late sign of this lifethreatening disorder, generalized edema typically develops rapidly. The edema is pitting and moderately severe. Accompanying it may be cool skin, hypotension, oliguria, tachycardia, cyanosis, thirst, anxiety, and signs of respiratory failure.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Any drug that causes sodium retention may aggravate or cause generalized edema. Examples include antihypertensives, corticosteroids, androgenic and anabolic steroids, estrogens, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen and naproxen.

♦ Treatments. I.V. saline solution infusions and internal feedings may cause sodium and fluid overload, resulting in generalized edema, especially in patients with cardiac or renal disease.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Position the patient with his limbs above heart level to promote drainage. Periodically reposition him to avoid pressure ulcers. If the patient develops dyspnea, lower his limbs, elevate the head of the bed, and administer oxygen. Massage areas where dependent edema has formed (for example, the back, sacrum, hips, and buttocks). Prevent skin breakdown in these areas by placing a pressure mattress on the patient’s bed. Restrict fluids and sodium, and administer a diuretic.

Monitor intake and output and daily weight. Also monitor serum electrolyte levels, especially sodium and albumin. Prepare the patient for blood and urine tests, X-rays, echocardiography, or an electrocardiogram.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Renal failure in children commonly causes generalized edema. Monitor fluid balance closely. Remember that fever or diaphoresis can lead to fluid loss, so promote fluid intake.

Kwashiorkor (protein-deficiency malnutrition) is more common in children than in adults and causes anasarca.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Elderly patients are more likely to develop edema for several reasons, including decreased cardiac and renal function and, in some cases, poor nutritional status. Use caution when giving older patients I.V. fluids or medications that can raise sodium levels and thereby increase fluid retention.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Teach patients with known heart failure or renal failure to watch for edema; explain that it’s an

important sign of decompensation that indicates the need for immediate adjustment of therapy. Also teach patients to weigh themselves every day at the same time with the same clothes on to track if they have an increase in weight, which may correspond to increased fluid retention.

important sign of decompensation that indicates the need for immediate adjustment of therapy. Also teach patients to weigh themselves every day at the same time with the same clothes on to track if they have an increase in weight, which may correspond to increased fluid retention.

Edema of the arm

The result of excess interstitial fluid in the arm, this type of edema may be unilateral or bilateral and may develop gradually or abruptly. It may be aggravated by immobility and alleviated by arm elevation and exercise.

Arm edema signals a localized fluid imbalance between the vascular and interstitial spaces. (See Understanding fluid balance, page 258.) It commonly results from trauma, venous disorders, toxins, or certain treatments.

Remove rings, bracelets, and watches from the patient’s affected arm because they may act as a tourniquet. Make sure the patient’s sleeves don’t inhibit drainage of fluid or blood flow.

Remove rings, bracelets, and watches from the patient’s affected arm because they may act as a tourniquet. Make sure the patient’s sleeves don’t inhibit drainage of fluid or blood flow.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

When taking the patient’s history, one of the first questions to ask is “How long has your arm been swollen?” Then find out if the patient also has arm pain, numbness, or tingling. Does exercise or arm elevation decrease the edema? Ask about recent arm injury, such as burns or insect stings. Also, note recent I.V. therapy, surgery, or radiation therapy for breast cancer.

Determine the edema’s severity by comparing the size and symmetry of both arms. Use a tape measure to determine the exact girth. Be sure to note whether the edema is unilateral or bilateral, and test for pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or nonpitting? page 259.) Next, examine and compare the color and temperature of both arms. Look for erythema and ecchymoses and for wounds that suggest injury. Palpate and compare the radial and brachial pulses. Finally, look for arm tenderness and decreased sensation or mobility. If you detect signs of neurovascular compromise, elevate the arm.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Angioneurotic edema. Angioneurotic edema is a common reaction that’s characterized by sudden onset of painless, nonpruritic edema in the hands, feet, eyelids, lips, face, neck, genitalia, or viscera. Although these swellings usually don’t itch, they may burn and tingle. If edema spreads to the larynx, signs of respiratory distress may occur.

♦ Arm trauma. Shortly after a crush injury, severe edema may affect the entire arm. It may be accompanied by ecchymoses or superficial bleeding, pain or numbness, and paralysis.

♦ Burns. Mild to severe edema, pain, and tissue damage may occur up to 2 days after an arm burn.

♦ Superior vena cava syndrome. Bilateral arm edema usually progresses slowly in this disorder and is accompanied by facial and neck edema. Dilated veins mark these edematous areas. The patient also complains of headache, vertigo, and vision disturbances.

♦ Thrombophlebitis. Thrombophlebitis, which can result from peripherally inserted central catheters or arm portacaths, may cause arm edema, pain, and warmth. Deep vein thrombophlebitis can also produce cyanosis, fever, chills, and malaise; superficial thrombophlebitis also causes redness, tenderness, and induration along the vein.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Envenomation. Envenomation by snakes, aquatic animals, or insects initially may cause edema around the bite or sting that quickly spreads to the entire arm. Pain, erythema, and pruritus at the site are common; paresthesia occurs occasionally. Later, the patient may develop generalized signs and symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, weakness, muscle cramps, fever, chills, hypotension, headache and, in severe cases, dyspnea, seizures, and paralysis.

♦ Treatments. Localized arm edema may result from infiltration of I.V. fluid into the interstitial tissue. A radical or modified radical mastectomy that disrupts lymphatic drainage may cause edema of the entire arm, as can axillary lymph node dissection. Also, radiation therapy for breast cancer may produce arm edema immediately after treatment or months later.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Treatment of the patient with arm edema varies according to the underlying cause. General care measures include elevation of the arm, frequent repositioning, and appropriate use of bandages and dressings to promote drainage and circulation. Provide meticulous skin care to prevent breakdown and formation of pressure ulcers.

Also, administer an analgesic and anticoagulant as needed.

Also, administer an analgesic and anticoagulant as needed.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Arm edema rarely occurs in children, except as part of generalized edema, but it may result from arm trauma, such as burns and crush injuries.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Warn the patient who has undergone a mastectomy or axillary lymph node dissection of the possibility of arm edema, and advise her not to have blood pressure measurements taken or phlebotomies performed on the affected arm. Teach the patient how to perform arm exercises after surgery to prevent lymphedema.

Edema of the face

Facial edema refers to either localized swelling—around the eyes, for example—or more generalized facial swelling that may extend to the neck and upper arms. Occasionally painful, this sign may develop gradually or abruptly. Sometimes it precedes onset of peripheral or generalized edema. Mild facial edema may be difficult to detect; the patient or someone who’s familiar with his appearance may report it before it’s noticed during assessment.

Facial edema results from disruption of the hydrostatic and osmotic pressures that govern fluid movement between the arteries, veins, and lymphatics. (See Understanding fluid balance, page 258.) It may result from venous, inflammatory, and certain systemic disorders; trauma; allergy; malnutrition; or the effects of certain drugs, tests, and treatments.

If the patient has facial edema associated with burns or if he reports recent exposure to an allergen, quickly evaluate his respiratory status: Edema may also affect his upper airway, causing a life-threatening obstruction. If you detect audible wheezing, inspiratory stridor, or other signs of respiratory distress, administer epinephrine. For patients in severe distress—with absent breath sounds and cyanosis—tracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or tracheotomy may be required. Always administer oxygen.

If the patient has facial edema associated with burns or if he reports recent exposure to an allergen, quickly evaluate his respiratory status: Edema may also affect his upper airway, causing a life-threatening obstruction. If you detect audible wheezing, inspiratory stridor, or other signs of respiratory distress, administer epinephrine. For patients in severe distress—with absent breath sounds and cyanosis—tracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or tracheotomy may be required. Always administer oxygen.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, take his health history. Ask if facial edema developed suddenly or gradually. Is it more prominent in early morning, or does it worsen throughout the day? Has the patient gained weight? If so, how much and over what length of time? Has he noticed a change in his urine color or output? In his appetite? Take a drug history and ask about recent facial trauma.

Begin the physical examination by characterizing the edema. Is it localized to one part of the face, or does it affect the entire face or other parts of the body? Determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting, and grade its severity. (See Edema: Pitting or nonpitting? page 259.) Next, take vital signs and assess neurologic status. Examine the oral cavity to evaluate dental hygiene and look for signs of infection. Visualize the oropharynx and look for any soft-tissue swelling.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Abscess, periodontal. This type of abscess, which usually results from poor oral hygiene, is commonly caused by anaerobic organisms. It can cause edema of the side of the face, pain, warmth, erythema, and a purulent discharge around the affected tooth.

♦ Abscess, peritonsillar. This complication of tonsillitis may cause unilateral facial edema. Other key signs and symptoms include severe throat pain, neck swelling, drooling, cervical adenopathy, fever, chills, and malaise.

♦ Allergic reaction. Facial edema may characterize both a local allergic reaction and anaphylaxis. A local reaction produces facial edema, erythema, and urticaria. In life-threatening anaphylaxis, angioneurotic facial edema may occur with urticaria and flushing. (See Recognizing angioneurotic edema, page 262.) Airway edema causes hoarseness, stridor, and bronchospasm with dyspnea and tachypnea. Signs of shock, such as hypotension and cool, clammy skin, may also occur.

♦ Cavernous sinus thrombosis. Cavernous sinus thrombosis is a rare but serious disorder that may begin with unilateral edema that quickly progresses to bilateral edema of the forehead, base of the nose, and eyelids. It may also produce chills, fever, headache, nausea, lethargy, exophthalmos, and eye pain.

♦ Chalazion. A chalazion causes localized swelling and tenderness of the affected eyelid, accompanied by a small red lump on the conjunctival surface.

♦ Conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis is an inflammation that causes eyelid edema, excessive

tearing, and itchy, burning eyes. Inspection reveals a thick purulent discharge, crusty eyelids, and conjunctival injection. Corneal involvement causes photophobia and pain.

tearing, and itchy, burning eyes. Inspection reveals a thick purulent discharge, crusty eyelids, and conjunctival injection. Corneal involvement causes photophobia and pain.

Recognizing angioneurotic edema

Most dramatic in the lips, eyelids, and tongue, angioneurotic edema commonly results from an allergic reaction. It’s characterized by rapid onset of painless, nonpitting, subcutaneous swelling that usually resolves in 1 to 2 days. This type of edema may also involve the hands, feet, genitalia, and viscera; laryngeal edema may cause life-threatening airway obstruction.

|

♦ Corneal ulcers, fungal. Accompanying red, edematous eyelids in this disorder are conjunctival injection, intense pain, photophobia, and severely impaired visual acuity. Copious amounts of a purulent eye discharge make the eyelids sticky and crusted. The characteristic dense, central ulcer grows slowly, is whitish gray, and is surrounded by progressively clearer rings.

♦ Dacryoadenitis. Severe periorbital swelling characterizes dacryoadenitis, which may also cause conjunctival injection, a purulent discharge, and temporal pain.

♦ Dacryocystitis. Lacrimal sac inflammation causes prominent eyelid edema and constant tearing. In acute cases, pain and tenderness near the tear sac accompany a purulent discharge.

♦ Dermatomyositis. Periorbital edema and a heliotropic rash develop gradually in this rare disease. An itchy, lilac-colored rash appears on the bridge of the nose, cheeks, and forehead. Localized or diffuse erythema, eye pain, and fever may also occur.

♦ Facial burns. Burns may cause extensive edema that impairs respiration. Additional findings include singed nasal hairs, red mucosa, sooty sputum, and signs of respiratory distress such as inspiratory stridor.

♦ Facial trauma. The extent of edema varies with the type of injury. For example, a contusion may cause localized edema, whereas a nasal or maxillary fracture causes more generalized edema. Associated features also depend on the type of injury.

♦ Frontal sinus cancer. This rare form of cancer causes cheek edema on the affected side, reddened skin over the sinus, unilateral nasal bleeding or discharge, and exophthalmos. Pain over the forehead and unilateral hypoesthesia or anesthesia may occur later.

♦ Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (shingles). In herpes zoster ophthalmicus, edematous and red eyelids are usually accompanied by excessive tearing and a serous discharge. Severe unilateral facial pain may occur several days before vesicles erupt.

♦ Hordeolum (stye). Typically, a hordeolum produces localized eyelid edema, erythema, and pain.

♦ Malnutrition. Severe malnutrition causes facial edema followed by swelling of the feet and legs. Associated signs and symptoms include muscle atrophy and weakness; anorexia; diarrhea; lethargy; dry, wrinkled skin; sparse, brittle, easily plucked hair; and decreased pulse and respiratory rates.

♦ Melkersson’s syndrome. Facial edema (especially of the lips), facial paralysis, and folds in the tongue are the three characteristic signs of this rare disorder.

♦ Myxedema. Myxedema eventually causes generalized facial edema, waxy dry skin, hair loss or coarsening, and other signs of hypothyroidism.

♦ Nephrotic syndrome. Commonly the first sign of nephrotic syndrome, periorbital edema precedes dependent and abdominal edema. Associated findings include weight gain, nausea, anorexia, lethargy, fatigue, and pallor.

♦ Orbital cellulitis. Sudden onset of periorbital edema marks this inflammatory disorder. It may be accompanied by a unilateral purulent discharge, hyperemia, exophthalmos, conjunctival injection, impaired extraocular movements, fever, and extreme orbital pain.

♦ Osteomyelitis. When osteomyelitis affects the frontal bone, it may cause forehead edema as well as fever, chills, headache, and cool, pallid skin.

♦ Preeclampsia. Edema of the face, hands, and ankles is an early sign of this disorder of

pregnancy. Other characteristics include excessive weight gain, severe headache, blurred vision, hypertension, and midepigastric pain.

pregnancy. Other characteristics include excessive weight gain, severe headache, blurred vision, hypertension, and midepigastric pain.

♦ Rhinitis, allergic. In allergic rhinitis, red and edematous eyelids are accompanied by paroxysmal sneezing, itchy nose and eyes, and profuse, watery rhinorrhea. The patient may also develop nasal congestion, excessive tearing, headache, sinus pain, and sometimes malaise and fever.

♦ Sinusitis. Frontal sinusitis causes edema of the forehead and eyelids. Maxillary sinusitis produces edema in the maxillary area as well as malaise, gingival swelling, and trismus. Both types are also accompanied by facial pain, fever, nasal congestion, a purulent nasal discharge, and red, swollen nasal mucosa.

♦ Superior vena cava syndrome. Superior vena cava syndrome gradually produces facial and neck edema accompanied by thoracic or jugular vein distention. It also causes central nervous system symptoms, such as headache, vision disturbances, and vertigo.

♦ Trachoma. In trachoma, edema affects the eyelid and conjunctiva and is accompanied by eye pain, excessive tearing, photophobia, and eye discharge. Examination reveals an inflamed preauricular node and visible conjunctival follicles.

♦ Trichinosis. This relatively rare infectious disorder causes sudden onset of eyelid edema with fever (102° F to l04° F [38.9° C to 40° C]), conjunctivitis, muscle pain, itching and burning skin, sweating, skin lesions, and delirium.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Diagnostic tests. An allergic reaction to contrast media used in radiologic tests may produce facial edema.

♦ Drugs. Long-term use of glucocorticoids may produce facial edema. Any drug that causes an allergic reaction (aspirin, antipyretics, penicillin, and sulfa preparations, for example) may have the same effect.

Ingestion of the fruit pulp of ginkgo biloba can cause severe erythema and edema and the rapid formation of vesicles. Feverfew and chrysanthemum parthenium can cause swelling of the lips, irritation of the tongue, and mouth ulcers. Licorice may cause facial edema and water retention or bloating, especially if used before menses.

Ingestion of the fruit pulp of ginkgo biloba can cause severe erythema and edema and the rapid formation of vesicles. Feverfew and chrysanthemum parthenium can cause swelling of the lips, irritation of the tongue, and mouth ulcers. Licorice may cause facial edema and water retention or bloating, especially if used before menses.♦ Surgery and transfusion. Facial edema may result from cranial, nasal, or jaw surgery or from a blood transfusion that causes an allergic reaction.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Administer an analgesic for pain, and apply cream to reduce itching. Unless contraindicated, apply cold compresses to the patient’s eyes to decrease edema. Elevate the head of the bed to help drain the accumulated fluid. Urine and blood tests are commonly ordered to help diagnose the cause of facial edema.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Normally, periorbital tissue pressure is lower in a child than in an adult. As a result, children are more likely to develop periorbital edema. In fact, periorbital edema is more common than peripheral edema in children with such disorders as heart failure and acute glomerulonephritis. Pertussis may also cause periorbital edema.

Edema of the leg

Leg edema is a common sign that results when excess interstitial fluid accumulates in one or both legs. It may affect just the foot and ankle or extend to the thigh, and may be slight or dramatic and pitting or nonpitting.

Leg edema may result from venous disorders, trauma, and certain bone and cardiac disorders that disturb normal fluid balance. (See Understanding fluid balance, page 258.) It may result from nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, acute or chronic thrombophlebitis, chronic venous insufficiency (most common), cellulitis, lymphedema, and the use of certain drugs. However, several nonpathologic mechanisms may also cause leg edema. For example, prolonged sitting, standing, or immobility may cause bilateral orthostatic edema. This pitting edema usually affects the foot and disappears with rest and leg elevation. Increased venous pressure late in pregnancy may cause ankle edema. Constricting garters or pantyhose may mechanically cause lowerextremity edema.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

To evaluate the patient, first ask how long he has had the edema. Did it develop suddenly or gradually? Does it decrease if he elevates his legs? Is it painful when touched or when he walks? Is it worse in the morning, or does it get progressively worse during the day? Ask about a recent leg injury or any recent surgery or illness that may have immobilized the patient.

Does he have a history of cardiovascular disease? Finally, obtain a drug history.

Does he have a history of cardiovascular disease? Finally, obtain a drug history.

Begin the physical examination by examining each leg for pitting edema. (See Edema: Pitting or nonpitting? page 259.) Because leg edema may compromise arterial blood flow, palpate or use a handheld Doppler device to auscultate peripheral pulses to detect any insufficiency. Observe leg color and look for unusual vein patterns. Then palpate for warmth, tenderness, and cords, and gently squeeze the calf muscle against the tibia to check for deep pain. If leg edema is unilateral, dorsiflex the foot to look for Homans’ sign, which is indicated by calf pain. Finally, note skin thickening or ulceration in the edematous areas.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Burns. Mild to severe edema, pain, and tissue damage may occur up to 2 days after a leg burn.

♦ Cellulitis. Caused by a streptococcal or staphylococcal infection that usually affects the legs, cellulitis produces pitting edema and orange peel skin along with erythema, warmth, and tenderness in the infected area.

♦ Cirrhosis. Cirrhosis commonly causes bilateral edema, which is associated with ascites, jaundice, and abdominal swelling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree