Dysuria and Vaginal Discharge

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Nearly 5% of patients seen in emergency departments present with complaints related to the genitourinary system. Dysuria (painful urination) and vaginal or urethral discharge are the most common complaints. There are three major causes of dysuria: vaginitis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and urinary tract infections (UTIs). Pharmacists are often asked for advice regarding potential self-care of dysuria and vaginal discharge with nonprescription medication. Therefore, understanding major causes and how to determine if the patient’s symptoms are appropriate for self-care are important skills. In addition, when counseling patients on the use of medications, understanding the symptoms and complications of the disease allows the pharmacist to provide necessary information. Finally, to evaluate the appropriateness of therapy or to advise a prescriber on appropriate therapy, the pharmacist needs to understand the process of differential diagnosis for dysuria and vaginal discharge.

• GENERAL APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH DYSURIA

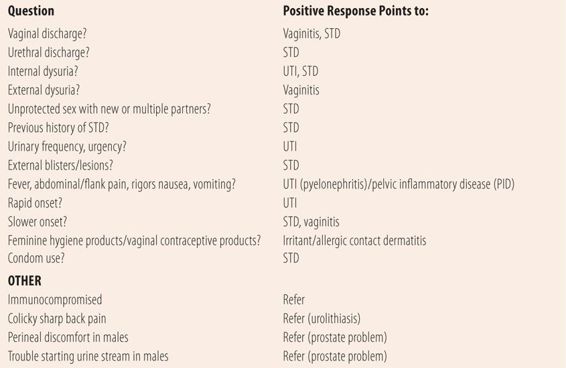

Since dysuria is a prominent symptom of three separate disorders, providers (including pharmacists) need to take a structured approach to assessing which disorder is the most likely cause of the patient’s dysuria. There are some key initial questions that will help the provider narrow his/her diagnostic focus and make the decision whether the patient is a candidate for self-treatment or needs to be referred (Table 16.1). Unfortunately, other than vaginitis, there are few genitourinary disorders that lend themselves to self-treatment, so positive responses to most questions require referral. For example, if a patient has a vaginal discharge and dysuria, it is possible, but unlikely that they have a UTI, and further questioning as to the specific cause of the vaginal discharge is warranted. Similarly, urethral discharges are usually representative of STDs. Dysuria, plus urinary frequency or urgency point to lower tract UTIs, whereas dysuria, plus systemic signs (nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal or flank pain, and rigors) point to an upper UTI (acute pyelonephritis). A vaginal discharge plus systemic symptoms point to possible pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Positive answers to these questions do not automatically make the diagnosis, but point to a diagnosis more likely than a UTI. Multiple positive answers frequently force the diagnostician to do a complete workup for all three common causes to arrive at a diagnosis.

| TABLE 16.1 | Initial Questions for Patients With Chief Complaint of Dysuria |

• VAGINITIS/VAGINAL DISCHARGE

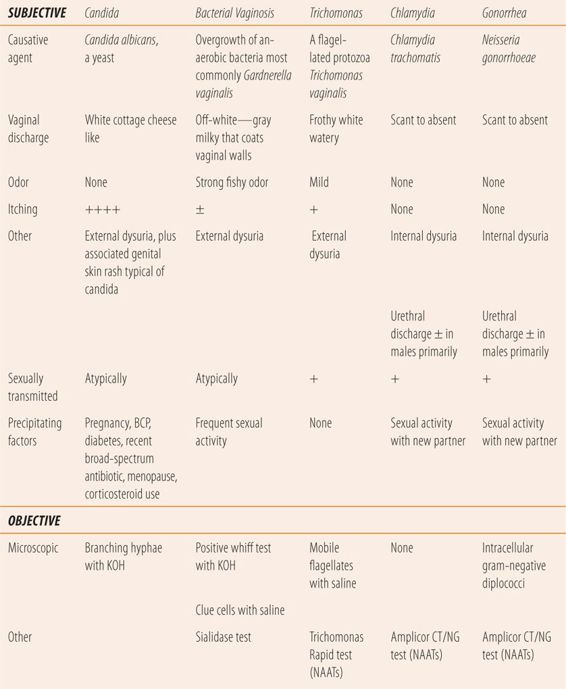

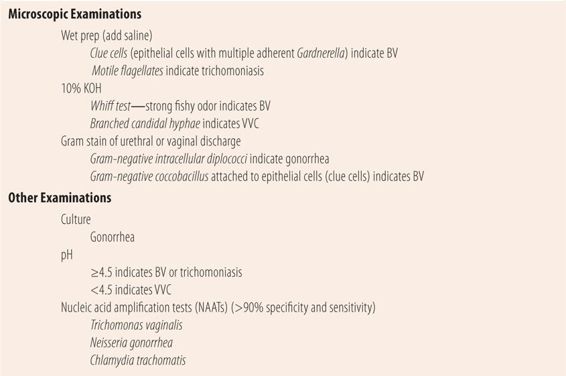

Classically, vaginal infections are characterized by the presence of an excessive or unusual vaginal discharge. Other vaginal symptoms can include odor, vulvovaginal irritation, pruritus, and painful intercourse. The primary urethral symptoms that can accompany a vaginal discharge are dysuria and urethral discharge. With a careful history, dysuria can be described by patients as internal or external. Internal dysuria is described as occurring at the beginning of voiding (where the urethra meets the bladder) and throughout the length of the urethra, due to inflammation and infection of the bladder and/or the entire urethra. Patients with UTIs and STDs tend to describe their dysuria as internal. Patients with vaginitis tend to describe their dysuria as external, e.g., not occurring until the labia or the outer 25% of the urethra. While not in itself diagnostic, it can be a valuable clue to distinguishing between causes of dysuria. While women with one of the common causes of vaginitis often present with dysuria and vaginal discharge, a large percentage may be asymptomatic initially. High-risk women (new or multiple sex partners or previous history of STD) require screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea, which usually requires a pelvic examination. While males who present with gonorrhea or chlamydia typically have a purulent urethral discharge, women may present with cervicitis as a primary finding in chlamydial and gonococcal infections or PID. Cervicitis is a purulent or mucopurulent discharge or bleeding after gentle passage of a cotton swab into the cervical os, during examination with a vaginal speculum. There are three common causes of vaginitis: bacterial vaginosis (BV), vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC), and trichomoniasis. Table 16.2 lists the subjective and objective characteristics used in the differential diagnosis of vaginal discharge. Classically, one drop or sample of the vaginal discharge, from the pelvic examination, is placed on two slides for microscopic examination. Next, to one slide a drop of saline is added and to the other a drop of 10% KOH is added (Table 16.3). Today there are newer and more accurate office diagnostic tests available. However, they are more expensive than the classic approach and most recommend their use, if the diagnosis is not clear.

| TABLE 16.2 | Differential Diagnosis of Vaginal Discharge |

| TABLE 16.3 | Testing Vaginal/Urethral Discharge Samples |

Bacterial Vaginosis

BV is not an STD, but there can be an association with sexual activity. Also, technically BV is not a vaginitis. However, it is the most frequently diagnosed cause of vaginal discharge in sexually active women. While the exact pathophysiology is not clearly understood, it appears that it is a disruption in the normal bacterial flora caused by the secretions and/or ejaculates of normal sexual activity raising vaginal pH. This leads to a predominance of several species including Gardnerella vaginalis, as well as Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides species. Fifty percent of women with BV are asymptomatic. The most common symptom is a fishy odor. The lack of odor makes BV unlikely, as does a normal pH, both of which are more typical of VVC. Upon pelvic examination, there is an off-white or gray vaginal discharge that adheres to the vaginal wall. The pH of the discharge is always above 4.5 and a normal pH (3.8 to 4.2) virtually eliminates BV as a cause. When a sample of the discharge is mixed with a 10% KOH solution, it gives off a strong fishy odor (whiff test). Microscopically, more than 20% of the epithelial cells have gram-negative coccobacillus (Gardnerella vaginalis) attached, i.e., clue cells. There is a more specific test that measures vaginal fluid sialidase activity that has >90% specificity and sensitivity, but due to its cost it may be reserved for situations where a specific diagnosis cannot be made by traditional methods.

Candida

VVC is the second most common cause of vaginal discharge. More than 75% of women will experience one episode of VVC in their lifetime. Intense itching is the predominant symptom and the lack of itching makes the diagnosis of VVC unlikely. Typically, there is a lot of inflammation and redness internally and externally on the labia. Red satellite lesions that are pathognomonic of candidal skin infections may be seen on the external genitalia and surrounding areas. While the discharge is typically described as white and cottage cheese like, many times it does not have the typical appearance, but may be seen as white plaques or patches on the vaginal wall. Microscopically, a sample of the discharge when mixed with 10% KOH will reveal branched hyphae typical of Candida species. Vaginal fluid pH is usually normal, but not greater than 4.5. Patients usually have one or more predisposing factors present. Since estrogens increase the susceptibility to VVC, women who are pregnant or on oral contraceptives are at increased risk. Similarly, high levels of glucose in vaginal fluid and urine promote the rapid growth of candida, so suboptimally controlled diabetes mellitus predisposes women to VVC. Candida albicans is normal vaginal flora, but their growth is held in check by the low vaginal pH created primarily by Lactobacillus species. Broad spectrum antibiotic therapy markedly reduces the number of Lactobacillus and allows the pH to rise, creating a vaginal environment that encourages candidal proliferation.

Since VVC is the only vaginitis that is amenable to self-care, the pharmacist needs to question the patient carefully before recommending any product. Patients amenable to self-care will present with several of the following symptoms: external dysuria, intense itching, red, irritated external genital area with potential satellite lesions, and have one or more of the predisposing factors. The patient with a vaginal discharge is best referred if there is a fishy or musty odor, internal dysuria or an absence of itching.

Recurrent VVC or VVC that does not respond to self-care products should prompt a referral. Many times VVC is the first sign of diabetes seen in women. In addition, while the vast majority of VVC is caused by Candida albicans, recurrence or resistance may represent VVC caused by nonalbicans Candida species such as Candida glabrata, which are historically more resistant to imidazole-containing vaginal products.

Trichomoniasis

Trichomonas vaginitis (TV) is caused by a motile flagellate protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, and is the least frequently seen cause of vaginitis. It is seen more commonly in women over 40 years of age and in women of African American descent. The signs and symptoms are not as specific as with BV or VVC, and many women are asymptomatic. The discharge is described as frothy, thin and watery, and white with occasional yellow or greenish tinges. Generally, the odor is mild to nonexistent and the pH of the discharge is greater than 4.5. Microscopically, a wet prep (saline) reveals motile flagellates slightly larger than a leukocyte. Microscopically examining a spun urine sample increases the identification of Trichomonas vaginalis compared with the wet prep alone. There is a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for Trichomonas vaginalis that, due to cost, may be reserved for situations where the diagnosis is unclear.

Chlamydia

Chlamydial genital infections are the most frequently reported infectious diseases in the United States. Chlamydia is most prevalent in patients 25 years of age and under, and it is commonly asymptomatic. Since complications in women include PID, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility, both CDC and USPSTF recommend that all sexually active women 25 years of age and under and older women with new or multiple sex partners be tested annually. Concomitant infection with gonorrhea is common; therefore, patients diagnosed with chlamydia and their partners should be treated for both diseases. Diagnosis is made using NAATs that are specific for Chlamydia trachomatis. The test is accurate for urine, urethral discharge, plus endocervical, vaginal, and rectal swabs. Patients testing positive for C. trachomatis should also be tested for gonorrhea, syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B.

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is the second most common bacterial STD. A majority of infections caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae are diagnosed in males because the painful urethral discharge causes them to seek medical attention. Among women, gonorrhea can be asymptomatic. Complications of gonorrhea are similar to chlamydia in women. While gram-negative diplococci, found within neutrophils, are diagnostic in male urethral discharge, the yield in women is much lower. Negative Gram stains, however, do not rule out gonorrhea. Like in chlamydia, NAATs are the diagnostic test of choice in women. They are accurate using urine, plus vaginal, endocervical, rectal and urethral swabs. Concomitant infection with chlamydia is common; therefore, patients diagnosed with gonorrhea and their partners should be treated for both diseases. Patients testing positive for N. gonorrhoeae should also be tested for chlamydia, syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B.

Noninfectious Causes

There are other noninfectious causes of vaginal discharge that make up roughly 10% of patients seen with vaginal discharges. Leukorrhea, a small amount of serous discharge containing vaginal debris, is not unusual and is normal particularly during pregnancy and in women on oral contraceptives. Allergic or irritant contact dermatitis to feminine hygiene products, latex condoms, or topical contraceptive creams/foams can cause vaginal symptoms including discharge. In perimenopausal women atrophic vaginitis should be considered. Retained tampons or other foreign bodies can also be a cause of vaginal odor, discomfort, and discharge.

• URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

UTI is the most common bacterial infection in women, accounting for 8.6 million ambulatory care visits annually in the US. Half of all women will experience at least one UTI in their lifetime. UTIs are classified in a variety of ways. First is to use anatomical locations. Lower tract UTIs are those primarily involving the bladder and urethra. Cystitis is the term most frequently used to describe lower tract infections. Upper tract UTIs are infections in the kidney(s), and pyelonephritis is the term commonly used to describe upper tract UTIs. UTIs can also be described as complicated and uncomplicated. An uncomplicated UTI is one that occurs in healthy premenopausal women who are not pregnant and have no functional or structural abnormalities in their urinary tract. All others, in addition to pregnant women and patients with functional urinary tract abnormalities, are termed complicated. Other complicated UTIs are those in children, males, patients with diabetes, and patients with indwelling catheters. Recurrent infections and relapsed UTIs are also termed complicated. Complicated infections require longer antibiotic therapy or prophylactic measures. Recurrent UTIs are defined arbitrarily as two infections within 6 months or three to four in 12 months, and each episode is caused by a different organism. Relapsed UTIs are recurrent infections, usually with the same organism, and typically occur in patients with structural abnormalities in their urinary tract.

Eighty to ninety percent of UTIs occur in sexually active females. The short, straight urethra plus the trauma of sexual intercourse force motile coliform bacteria from the introitus (labia and entrance to vagina) into the urethra and bladder. From there, the bacteria may migrate up the ureters and into the kidneys, causing an upper tract UTI. There are multiple other predisposing factors for UTIs. During pregnancy, as the uterus enlarges, it creates temporary structural abnormalities in the urinary tract, predisposing pregnant women to upper and lower tract UTIs, which can lead to miscarriage and other complications. Also as the uterus grows, the pressure on the bladder increases urinary frequency and urgency, potentially masking signs of a UTI. In addition, upper tract disease is frequently asymptomatic in pregnancy. Detection of asymptomatic pyelonephritis is the rationale for pregnant women to have urine cultures done at the first prenatal visit, at 12 to 16 weeks and in the third trimester. Sub-optimally controlled diabetes mellitus is a risk factor because higher plasma glucose levels increase glucose in the urine, which provides stimulus for bacterial growth. In addition, plasma glucose levels ≥ 200 mg/dL reduce neutrophil activity, reducing the ability to fight bacterial infections. Urinary tract instrumentation, especially indwelling catheters, facilitate invasion of bacteria. Males with prostate problems may not fully void, leaving residual urine in the bladder that promotes bacterial growth.

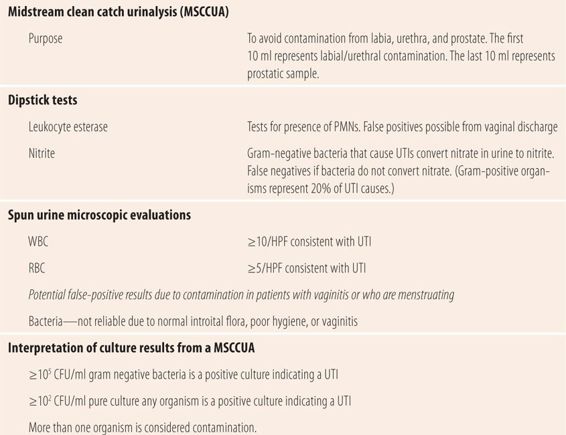

Diagnosis of a UTI requires a careful history and some laboratory testing (Table 16.4). It is sometimes difficult to accurately diagnose a UTI based on symptoms alone. Patients with cystitis present with dysuria (internal), frequency, urgency and possibly hematuria and may have suprapubic pain near completion of voiding. In the absence of a vaginal discharge, these symptoms are 90% predictive of a UTI. As previously discussed, the provider needs to rule out STDs and common causes of vaginal discharge, usually by history. While the symptoms of cystitis point to a bladder infection, 50% of cystitis patients also have what is called silent pyelonephritis or an asymptomatic upper tract UTI. Classical pyelonephritis presents with fever, nausea, vomiting, flank pain, and/or abdominal pain with or without cystitis symptoms. However, large percentages of pregnant women and children may be asymptomatic and still have upper tract disease. The causative bacteria in UTIs are usually normal GI flora that contaminate the introitus due to its close proximity to the anus and fecal matter. In 75% to 85% of uncomplicated UTIs, the infecting organism is a gram-negative coliform bacteria, Escherichia coli. Staphylococcus saprophyticus, the second leading cause of UTIs, is a gram-positive organism and is found in 10% to 20% of cultures. The remaining causative organisms are also fecal flora, usually other coliforms or enterococcus.

| TABLE 16.4 | Urine Testing for Urinary Tract Infections |

Classically, all patients got a midstream clean catch urinalysis with culture and susceptibility (MSCCUA with C&S) if a UTI was suspected. Now, with newer technology and increased clinical evidence, the culture and susceptibility portion is limited to specific situations, which will be discussed later. The purpose of the MSCCUA is to avoid contamination from the labia, urethra, and prostate. The first 10 to 20 ml of urine flow contains any bacteria in the urethra and on the labia. The last 10 ml in males potentially has bacteria from the prostate. The method for the MSCCUA is very specific. Wash the labia with soap and water, rinse with water, and pat dry with sterile 4 × 4 gauze pads. While holding the labia apart, start the urine stream, stopping after 10 to 20 ml. Place the sterile collection container in front of the urine stream and collect 20 to 100 ml of urine. Stop the stream and remove the cup from the stream, then finish emptying the bladder into the toilet. During the study that established parameters for interpreting the MSCCUA culture, nurses’ aides went into the restroom with the patient, washed the external genitalia with Tincture of Green Soap, rinsed it off with a squeeze water bottle, and ensured the process was done correctly. In actual practice not all of those steps are followed correctly, so most specimens are not true MSCCUAs. Today, patients are given a kit and frequently, with little or no instruction, are asked to go into the restroom and urinate into the jar found in the kit. Not surprisingly, there have been multiple problems with interpreting MSCCUA culture results. The gold standard for diagnosing a UTI is >105 CFU/ml (colony-forming units) and was developed from the study where the clean catch process was religiously followed. However, at the time, coliform bacteria were thought to be the only cause of UTIs, so pure cultures of gram-positive organisms, such S. saprophyticus or enterococcus, were considered contamination! If unable to process the urine sample quickly, the standard procedure is to place the urine container in a refrigerator to prevent coliform bacteria from overgrowing at room temperature and invalidating the sample. Unfortunately, gram-positive pathogens are fastidious and may die with exposure to cold, so cultures from infections due to gram-positive organisms were many times mislabeled as no growth. Also in cystitis, the frequent emptying of small amounts of urine from the bladder does not allow the bacteria any time to reproduce, resulting in counts of less than 105 CFU/ml. More recent studies, comparing cultures from sterile needle suprapubic aspiration of infected urine from the bladder to those obtained with an MSCCUA clearly demonstrated that any culture of a single organism with ≥102 CFU/ml was diagnostic for a UTI. Cultures with multiple organisms regardless of the count are considered contamination, and the specimen and analysis needs to be repeated with proper instruction or assistance.

In addition to culturing the urine specimen, it is spun down and several drops of the sediment are examined under the microscope. The remaining urine is tested for the presence of glucose, ketones, and protein. The most important part of the microscopic examination is counting the number of red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells (WBCs), and epithelial cells per high power field (hpf). The number of epithelial cells per hpf is indicative of the “cleanness” of the MSCCUA. Less than five or a few epithelial cells confirms that the correct procedure for the MSCCUA was followed. Results that list TNTC (too numerous to count) or greater than 10/hpf suggest procedures were poorly followed and results need to be interpreted in that light. In a well-collected MSCCUA, greater than 10 WBCs/hpf is consistent with a UTI. Similarly, inflammation in kidney tissue and the bladder may result in hematuria. More than 5 RBCs/hpf is consistent with a UTI. Finally, the finding of any bacteria in an unspun urine specimen is consistent with >105 CFU/ml and is diagnostic for a UTI.

Currently, the laboratory diagnostic gold standard in suspected UTI is still the MSCCUA with microscopic analysis of the spun specimen. The availability of dipstick diagnostic strips for the presence of leukocyte esterase (LE) and nitrite and evidence from clinical studies has markedly reduced the indication for the use of culture and susceptibility testing of the MSCCUA. Urine dipsticks for office use are now available that test for both LE and nitrite. LE is produced by neutrophils that release esterases as part of their defense against bacterial infections. They are also used to detect bacteria in amniotic and ascites fluids. Most common gram-negative bacteria that cause UTIs convert nitrate to nitrite. Positive LE and nitrite tests in a urine sample are diagnostic of a UTI in a patient with typical UTI symptoms. However, each test has its limitations. Since 20% of UTIs are caused by gram-positive organisms, the nitrite test will be negative in those cases, as will UTIs caused by Pseudomonas species. LE can give false-positive results especially if a vaginal discharge is present and MSCCUA procedures are not carefully followed. Both may be negative in a patient who has severe frequency and urgency since the levels of bacteria and WBCs in the small volumes of urine may not be high enough to detect either nitrite or LE.

Urine cultures are used to confirm UTIs and provide specific information about their antibiotic susceptibility. When should urine be cultured? Most guidelines and experts agree. All patients with complicated UTIs should have culture and susceptibility testing on their MSCCUA (children, males, structural abnormalities, pregnancy). Also included are patients suspected of acute pyelonephritis, those with diabetes mellitus or who are immunosuppressed, patients with suspected relapse or treatment failures, and those with an unclear diagnosis from the history and physical examination. The main problem with urine cultures and susceptibilities is that it takes 48 hours to get the results, so regardless of the results almost all antibiotic therapy of UTIs is initially empiric.

Given our knowledge of the limitations of laboratory diagnostic testing, two basic approaches to the diagnosis and treatment are used in healthy sexually active women with symptoms of uncomplicated acute cystitis. First, empiric antibiotic therapy, usually short course (3 to 5 days), is implemented after a careful history eliminates other causes. Several studies have shown that in women with recurrent cystitis self-diagnosis and treatment with an on-hand antibiotic is highly effective and reduces the need for laboratory tests. Second, in addition to a careful history, an MSCCUA is obtained and dipstick testing for LE and nitrite is done to confirm the presence of a UTI before short-course antibiotics are prescribed. Finally, if the history does not point to a more specific cause, then a complete pelvic examination accompanied by testing for STDs and vaginitis plus MSCCUA are required to accurately diagnose the cause of dysuria.

In patients with a UTI, if the causative bacteria are susceptible to the empiric antibiotic therapy that is prescribed, the symptoms of dysuria, frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain will quickly abate in as little as several hours. Systemic symptoms of acute pyelonephritis may take 24 hours to markedly improve. When counseling patients on antimicrobial medication for a UTI, the pharmacist should advise them that if the symptoms are not much better within 24 hours or totally gone by 48 hours, they should call the provider. Similarly, if a patient has been given oral antibiotics for a UTI, the pharmacist should inquire about potential nausea and vomiting due to acute pyelonephritis, which might interfere with oral therapy. Patients with nausea and/or vomiting are usually given a single injection of a long-acting antibiotic and instructed to wait for 24 hours before starting the oral therapy. If the patient received an antibiotic injection, the pharmacist should verify that the patient is to wait 12 to 24 hours (until the nausea disappears) to begin oral therapy. In patients with nausea and vomiting who have not received an injection, the provider should be notified of the potential problem before dispensing.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Bremnor JD, Sadovsky R. Evaluation of dysuria in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1589-1596.

2. Hainer BL, Gibson MV. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:807-815.

3. Ilkit M, Guzel AB. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidosis: a mycological perspective. Critic Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:250-261.

4. Donders G. Diagnosis and management of bacterial vaginosis and other types of abnormal vaginal flora: a review. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2010;65:462-473.

5. McClosky CR. Updated office testing skills for vaginal infections. Nurse Pract. 2010;35:46-52.

6. Mylonas I, Bergauer F. Diagnosis of vaginal discharge by wet mount microsopy: a simple and underated method. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2011;66:359-368.

7. Borhart J, Bimbauer DM. Emergency department management of sexually transmitted infections. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:587-603.

8. Anonymous. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59:1-109, RR-12.

9. Lane DR, Takhar SS. Diagnosis and management of urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:539-552.

10. Hooton TM. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree