Dysplasia in Barrett Esophagus

Elizabeth A. Montgomery, MD

Key Facts

Clinical Issues

No metastatic potential by itself

High-grade dysplasia (HGD)

In pooled data about 30% of patients with HGD progress to invasive adenocarcinoma

Low-grade dysplasia (LGD)

Regression to no dysplasia in about 2/3

Persistent LGD in about 20%

Progression to HGD/cancer in 13-15%

Microscopic Pathology

IFD: Uncertain whether process is reparative or neoplastic

Inflammation/erosions often a factor

Often surface maturation is present

LGD: Slightly crowded glands

Reduced surface maturation

Nuclei at surface are larger than those of nondysplastic Barrett mucosa

HGD: No surface maturation

Lost nuclear polarity, including at surface

Top Differential Diagnoses

Low-grade dysplasia

Reactive changes

IFD category has obviated some problems with this distinction

High-grade dysplasia

Intramucosal carcinoma

Somewhat subjective

Nucleoli, intraluminal necrosis, and syncytial effacement of lamina propria are features of early invasion

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations

Indefinite for dysplasia (IFD)

Low-grade dysplasia (LGD)

High-grade dysplasia (HGD)

Synonyms

Columnar epithelial dysplasia

Definitions

Neoplastic change confined to gland in which it arose

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

May have reflux symptoms but often asymptomatic

Treatment

Options, risks, complications

Esophagectomy: Reserved for HGD

Standard in 1990s but has fallen from favor with advent of newer techniques

High morbidity and mortality, especially in low-volume centers

Higher initial costs and results in more frequent minor complications

Usually curative

Mucosal ablation methods (“endotherapy”)

Photodynamic therapy

Endoscopic endoluminal radiofrequency ablation (using the Barrx device)

Cryotherapy

Laser therapy

All of these endoscopic treatments can be complicated by strictures

Associated with higher risk of tumor progression, although still uncommon

Endoscopic mucosal resection

Prognosis

No metastatic potential by itself

Risk of progression to invasive carcinoma is key and informs suggested surveillance and treatment

In pooled data about 30% of patients with HGD progress to invasive adenocarcinoma

About 6 per 100 patient-years

In patients with LGD, regression to no dysplasia about 65%, persistent LGD in about 20%, and progression to HGD/cancer in 13-15%

Follow-up: Modified from American College of Gastroenterologists guidelines

Negative for dysplasia

Confirm with 2 EGDs with biopsy within 1 year

Follow-up endoscopy every 3 years

LGD (and IFD)

Confirm: Repeat EGD with biopsies within 6 months to ensure there is no HGD

Expert pathologist confirmation

Follow-up endoscopies at 1-year intervals until no dysplasia identified on 2 consecutive endoscopies

HGD

Repeat EGD with biopsies to rule out invasive carcinoma within 3 months

Expert pathologist confirmation

Endoscopic resection

Continued 3-month surveillance or intervention based on results and patient

MACROSCOPIC FEATURES

Routine Endoscopy

Dysplastic mucosa often indistinguishable from nondysplastic Barrett mucosa

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

Key Descriptors

Predominant pattern/injury type

Neoplastic

Predominant cell/compartment type

Epithelial, glandular

Histologic features

Neoplastic appearing nuclei

No invasive carcinoma

Indefinite for Dysplasia

Uncertain whether process is reparative or neoplastic

Inflammation/erosions often a factor

Some nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia

Surface maturation is often present

Rare cases show “basal crypt dysplasia” pattern, but usually surface maturation is feature of repair

Normal to have some nuclear enlargement in deep glands of nondysplastic Barrett mucosa

Tangential embedding of such glands can be a factor and lead to overinterpretation of dysplasia

Low-Grade Dysplasia

Slightly crowded glands

“Upside down” goblet cells

Reduced surface maturation

Hyperchromatic nuclei at surface

Nuclei at surface are larger than those of nondysplastic Barrett mucosa

These features correlate well with image analysis findings

Image analysis not practical for clinical use but corroborates routine morphologic findings

Maintained nuclear polarity

Long axes of nuclei are perpendicular to basement membrane

Minimal nuclear membrane irregularity

Inflammation typically minimal

High-Grade Dysplasia

Crowded glands

No surface maturation

Lost nuclear polarity, including at surface

Nuclei have lost organized relationship to basement membrane

Nuclear membrane irregularities

More readily identified in material fixed in Bouin solution or Hollande fixative

Hyperchromatic nuclei

In most cases, internal control identified for comparison of nuclear hyperchromasia

Sometimes presents as nodule visible at endoscopy

Nucleoli not prominent

Occasional cases infiltrated by neutrophils

Possible influence of elaborated cytokines or chemotaxis factors

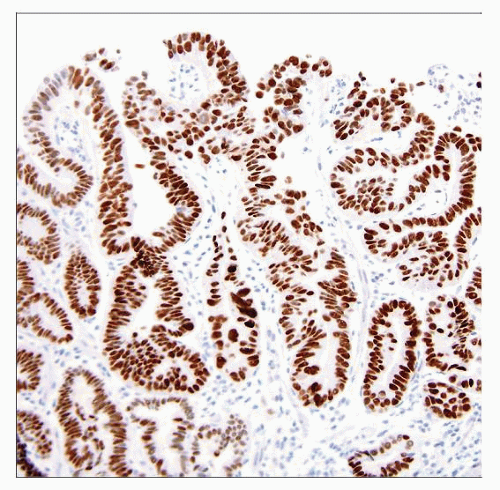

ANCILLARY TESTS

Immunohistochemistry

Usually not required for diagnosis, but many observers find p53 and Ki-67 labeling helpful

Caution: p53 labels about 90% of HGD

Subset is unlabeled

p53 in LGD has correlated with progression to HGD in some studies

Routine H&E remains best “marker” of progression to cancer

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Low-Grade Dysplasia

High-Grade Dysplasia

Distinguish HGD from intramucosal carcinoma

Somewhat subjective

Nucleoli, intraluminal necrosis, and syncytial effacement of lamina propria are features of early intramucosal invasion

On endoscopic mucosal resection samples, immunohistochemical more easily distinguished from HGD

Duplicated muscularis mucosae can result in confusion about depth of invasion

Finding ulcers associated with HGD raises possibility of unsampled invasive carcinoma

SELECTED REFERENCES

1. Rastogi A et al: Incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus and high-grade dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 67(3):394-8, 2008

2. Schembre DB et al: Treatment of Barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia: a comparison of endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 67(4):595-601, 2008

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree