This chapter presents the current status of dysphagia management in acute-care hospitals, focusing on the speech-language pathologist’s (SLP’s) involvement from the time of the initial consultation until the patient is discharged from the hospital. The types of screening and assessment tools utilized by the SLP are described in the context of cost containment and the integration of treatment into the diagnostic procedure for swallowing disorders (dysphagia). The SLP’s involvement with other professionals in the management of dysphagia in the acute-care setting is described. The competencies needed by the SLP at each stage of involvement with the dysphagic patient are outlined. In addition, protocols are presented for the screening, assessment, and treatment of the oropharyngeal dysphagic patient. Case studies are used to illustrate several critical points.

10.1 Nature of the Dysphagic Population in the Acute-Care Setting

Cost containment is driving every aspect of patient care in the acute-care setting, as in most other levels of health care. This translates to a relatively short stay in an acute-care setting for most patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia. The population of patients with dysphagia typically seen in acute care are those who have suffered a stroke, head injury, or spinal cord injury; those with progressive neurologic disease, such as Parkinson’s disease, motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, etc.; and patients receiving treatment for head and neck cancer, systemic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and dermatomyositis, etc. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 SLPs in acute care also often see patients on an outpatient basis who are referred for complaints of swallowing difficulty and have no known medical diagnosis. For this type of patient, the SLP often serves as a triage officer who assesses the patient’s oropharyngeal swallow function as well as speech, voice, and respiratory function and makes the appropriate referrals to a physician for a final diagnosis of the underlying cause of the dysphagia. Our data show that, in most cases, patients with complaints of oropharyngeal dysphgia most often have had neurologic damage or have undiagnosed neurologic disease, including brainstem stroke, motor neuron disease, Parkinson’s disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, multiple sclerosis, or brainstem tumor. 9

Numerous clinical anecdotes and experiences indicate that the most cost-effective care plan for the patient with a complaint of oropharyngeal dysphagia is a referral to an SLP for a modified barium swallow or videofluoroscopic (VFS) study of oropharyngeal swallow. Following this study, the SLP can make a referral to a particular specialty physician, usually neurology, for further diagnostic work-up. Unfortunately, many patients with a complaint of oropharyngeal dysphagia are referred for VFS studies only after they have already been seen by several physicians and have had numerous medical tests at a high cost to the health care system.

10.1.1 Case Study 1

A 94-year-old woman was referred by the gastroenterology service because she had a chronic bronchial infection of no known etiology. She had been treated for bronchitis for 6 months by a pulmonologist but no antibiotics were clearing the infection. The pulmonologist, becoming frustrated, referred her to an otolaryngologist for assessment to determine whether there might be some otolaryngologic reason for the bronchitis. The otolaryngologist, after examining her, referred her to gastroenterology for possible reflux disease. The gastroenterologist, after talking with her and her family, thought that dysphagia might be the reason for her bronchitis and referred her to speech-language pathology for swallowing assessment. An informal interview with the patient and observation of her behaviors revealed some degree of thoracic rigidity, a shuffling gait, and a masked facies, all typical of Parkinson’s disease. VFS examination (the modified barium swallow) revealed swallowing problems typical of Parkinson’s disease, including a repeated tongue-pumping action making oral transit 10 to 15 seconds per swallow, a delay in triggering the pharyngeal swallow, and residue in the valleculae after the swallow, indicating poor tongue-base action. This residue was chronically aspirated after the swallow. With the patient’s chin down, the aspiration was eliminated. The patient was counseled that her swallowing problem might be of a neurologic origin and she was referred to a neurologist familiar with swallowing disorders associated with neurologic disease. She was hospitalized for an in-depth work-up and was found to have Parkinson’s disease. Throughout her hospitalization, she was fed using the chin-down compensatory posture to facilitate her tongue-base motion and to improve the clearance of the valleculae and thus reduce or eliminate the aspiration. She was placed on antiparkinsonian medications, which resulted in improvement of the pharyngeal aspects of her swallowing problem and in elimination of the aspiration as revealed by repeat VFS study. Her bronchitis cleared up when the aspiration was eliminated.

If the patient had been initially referred to an SLP in an acute-care setting, the costs for numerous unnecessary referrals would have been saved and the patient would have had an earlier medical diagnosis. The competencies needed by the SLP to serve in this capacity include knowledge of neurologic disease processes and damage and their characteristic swallowing disorders at various points in recovery or degeneration, and skills in conducting and interpreting VFS studies.

10.2 Screening the Initial Referral

The SLP’s initial contact with a dysphagic patient is often a 10- to 15-minute bedside screening designed to determine whether the patient is exhibiting signs of an oral or a pharyngeal dysphagia or both, because the in-depth assessment procedures for the two dysphagia loci are quite different. 9, 10 The screening procedure typically assesses the following patient characteristics: (1) general level of alertness; (2) general secretion levels in the mouth, throat, and chest; (3) awareness of secretions, as exhibited by attempts to wipe away drooling, throat clearing, or coughing and attempts to clear chest secretions; (4) vocal quality (i.e., hoarse or gurgly); (5) history of any pneumonias; (6) obvious reduction in oromotor control; (7) history of neurologic insult or other neurologic or structural damage; and (8) medical diagnosis. With this information from an initial screening, the SLP may immediately recognize that the patient is at high risk for pharyngeal dysphagia because of a disorder in the triggering of the pharyngeal swallow or in any one of the neuromotor aspects that comprise the pharyngeal swallow itself, and that the patient requires an in-depth physiologic assessment to identify the physiologic or anatomical disorder responsible for the dysphagia. Usually this assessment is a modified barium swallow. If the screening identifies the patient’s dysphagia focus as in the oral cavity, then a detailed bedside examination will be completed to identify the nature of the problem and to enable the clinician to initiate the therapy as well as to develop a compensatory diet plan to enable the patient to return to oral intake as quickly as possible. At times, the screening cannot determine the locus of the dysphagia to the SLP’s satisfaction, and a modified barium swallow is recommended to define the patient’s swallow physiology.

10.2.1 Case Study 2

A 93-year-old woman with Alzheimer dementia was referred for a VFS study of oropharyngeal swallowing because she had begun to refuse to eat and to spit food from her mouth. The pre-radiographic screening revealed a patient with severe dementia, unable to follow any instructions, and only variably alert. The clinician observed that the patient refused placement of any food in her mouth when nursing attempted to feed her. If any food did enter her mouth, she would immediately spit it out and turn her head away. Observing this behavior, the clinician timed the attempts at food placement and found that each attempt took 2 to 3 minutes and then was unsuccessful as the patient pushed out anything that entered her mouth. The clinician then talked with the patient’s referring physician about the patient’s need for nonoral nutrition and also indicated that a radiographic study would be inappropriate because the patient would not get adequate nutrition or hydration even if her swallowing physiology was normal because of the behavioral and neurologic issues involved in the dementia. After this discussion, the referral for the modified barium swallow was canceled and the patient’s family was counseled regarding the need for nonoral nutrition.

10.2.2 Case Study 3

A 35-year-old man who suffered a brainstem stroke was referred to a speech-language pathology service 2 days after his stroke for screening for dysphagia. The chart revealed that the stroke was a large medullary lesion, that the patient had indicated complaints of dysphagia, and that the nursing staff had observed coughing during attempts to feed the patient. The diagnosis of brainstem stroke in the presence of patient complaints and observable symptoms is adequate to refer for a modified barium swallow. Brainstem stroke, particularly medullary, almost always involves damage to the timing of pharyngeal triggering and laryngeal elevation, as well as unilateral pharyngeal wall paresis and sometimes a vocal fold adductor paresis. In this case, the medical diagnosis is enough to immediately refer for a radiographic study because of the extremely high incidence of pharyngeal problems after medullary stroke. Even if the clinician could predict the types of pharyngeal problems that are present, the severity of these problems varies tremendously from patient to patient, requiring radiographic study to define them and to examine the effects of compensatory and other rehabilitation procedures on the swallow. Some of these patients can immediately return to at least partial oral intake using compensatory procedures.

The competencies needed by the SLP to screen for dysphagia include knowledge of signs and symptoms of dysphagia and medical diagnoses frequently causing dysphagia, and skill in observation of patient behavior and oromotor control.

10.3 In-Depth Clinical/Bedside Examination

Once the SLP has identified the general locus of the patient’s dysphagia (i.e., oral or pharyngeal) the clinician proceeds with an in-depth bedside/clinical assessment.

10.3.1 Review of the Patient’s Medical Chart

Prior to entering the patient’s room, the clinician should carefully review the patient’s medical chart, focusing particularly on the medical diagnosis, any prior or recent medical history of surgical procedures, trauma, neurologic damage, etc., as well as the patient’s current medications. There is a growing body of literature on the nature of swallowing disorders that result from particular medical diagnoses. Therefore, after defining the medical diagnosis, the clinician should immediately consider what physiologic or anatomical swallowing disorders are typical of that diagnosis. Unfortunately, the swallowing dysfunction of the vast majority of the patients seen by SLPs in the acute-care setting is not the result of a single diagnosis. Instead, their swallowing ability reflects all of the neurologic and structural damage they have sustained over the years, chronic medication, and other factors influencing the patient’s medical status. However, knowing the medical diagnosis and recalling the particular swallowing disorders that are characteristic of that diagnosis can alert the clinician to watch for those possible swallowing problems. If a consultation was obtained with a neurologist or otolaryngologist, the assessment report should be reviewed. History of any respiratory problems should also be identified, including the need for mechanical ventilation or a tracheostomy tube, the conditions under which it was placed (emergency or planned), and the length of time it was present. In general, any emergency procedure, such as emergency tracheostomy or intubation, will tend to cause more scar tissue than a planned procedure. Any history of gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction should be noted. A prior history of dysphagia from an earlier stroke or head injury, for example, should be highlighted even if the patient or family indicates that the patient returned to oral intake with no apparent difficulty after the prior dysphagia. Very few patients return to entirely normal swallowing after having had a prior dysphagia. Most dysphagic patients become functional swallowers, meaning that they exhibit no aspiration, but they have a slightly slower swallow with more residue than normal subjects their age and gender. Thus, it should be anticipated that a second injury causing dysphagia will result in more significant swallowing disorders than single first-time damage.

Medical chart review should also reveal the patient’s current nutritional status and the presence of any nonoral nutritional support, such as a nasogastric tube, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) (placed under local anesthetic), a surgical gastrostomy, or a jejunostomy (both surgical procedures requiring general anesthesia). Intravenous feeding (e.g., total parenteral nutrition), as well as any other nutritional supplements, should also be noted in the patient’s chart. The clinician should also be able to identify the patient’s general progress as well as prognosis from this chart review. The presence of any advance directives should also be identified. An advance directive may be a living will or a durable medical power of attorney. In either case, patients are generally stating their wishes regarding their care at a time of severe illness when no recovery is deemed possible.

10.3.2 Bedside Clinical Assessment

The bedside clinical assessment addresses the appearance and function of the patient’s lips, tongue, velopharyngeal region, pharyngeal walls, and larynx, as well as the patient’s awareness of sensory stimulation. 9 The physiology of some of these structures can be easily assessed at the bedside, whereas others can be examined accurately only in a radiographic or other instrumental study. The clinical assessment typically begins with an examination of the anatomical structure of the oral cavity, including its symmetry, and the presence of any scar tissue indicating surgical or traumatic damage. The oral examination should also note the presence and status of any oral secretions, especially the pooling of secretions or excessive, dried secretions. In general, the locus of excess secretions in the oral cavity indicates areas of lesser lingual control or injury.

The clinician’s oromotor assessment should then progress to examination of strength, range of motion, and coordination of the lips, tongue, and palate for speech and nonspeech tasks, as well as observation of lingual function and lip closure while the patient produces any spontaneous swallows. The clinician also notes the frequency of spontaneous swallowing. There is some initial evidence that the frequency of spontaneous swallows is significantly lower in patients who are hospitalized, have dysphagia, and aspirate than in those who do not aspirate. 11 The clinician should count swallows in a 5-minute period by observing or feeling the laryngeal motion in the patient’s neck. Normal saliva swallowing occurs at the rate of about one or two per 5-minute period in awake normal adults. ▶ Table 10.1 lists the voluntary tasks to be elicited from the patient during the bedside/oromotor assessment. In general, at the bedside, the clinician’s goals should be to assess swallow physiology without placing the patient at increased risk of food entering the airway (aspiration). Assessment of chewing and lingual control of material in the mouth can be tested safely at the bedside utilizing cloth rather than food. To this end, the clinician can bring four taste stimuli: lemon juice (sour), bitters (bitter), saline solution (salty), and sugar water (sweet). In addition, the clinician should bring 4 × 4 gauze squares as well as 4 × 4 squares of satin and burlap. The three types of cloth represent three food consistencies (burlap, rough food; satin, smooth food; and gauze, intermediate texture). By wrapping each 4 × 4 square of cloth around a flexible, disposable straw, the clinician can dip one end of the 4-inch roll into one of the flavors (making it as cold as desired), squeeze out the excess liquid from the cloth, and place the dampened end of the cloth containing the desired texture, flavor, and temperature into the patient’s mouth. Then the clinician can observe the patient’s reaction to the various combinations of stimuli and identify those particular stimuli that result in the most normal oromotor activity, such as chewing, lateralizing, lifting the tongue tip, etc. Whatever combination of textures, tastes, and temperatures elicits the most normal motor activity is the one that should be introduced in any radiographic or other instrumental study to follow.

Labial |

Range of motion |

Lip spread (/i/) |

Lip rounding (/u/) |

Asymmetry: right _____ left _____ |

Lip closure at rest |

Lip closure on rapid repetitive /pa/ |

Lip closure during sentence repetition “Please put the papers by the back door.” |

Lingual |

Range of motion |

Protrusion |

Elevation of tip (mouth open widely) |

Elevation of back (mouth open widely) |

Point to right side |

Point to left side |

Retraction |

Asymmetry: right _____ left _____ |

Rapid repetitive lateralization |

Rapid repetitive elevation |

Tip alveolar contact on repeated /ta/ |

Tip alveolar contact during sentence repetition “Take time to talk to Tom.” |

Fine lingual shaping during sentence repetition “Say something nice to Susan on Sunday” |

Back velar contact on rapid repetitive /ka/ |

Back velar contact during sentence repetition “Can you go get the garbage cans?” |

Chewing: ability to lateralize gauze, chew on it, return it to midline, and move it to the other side |

Velar function |

Elevation on prolonged /a/ |

Retraction on prolonged /a/ |

Symmetry of motion |

Oral sensitivity—patient awareness of: |

Light touch—tongue tip |

Light touch—left side |

Lateral margin of tongue |

Light touch—right side |

Lateral margin of tongue |

Posterior tongue |

Anterior faucial arch |

Cheek |

Laryngeal examination |

Vocal quality on prolonged /a/ (hoarse, gurgly) |

Strength of voluntary cough |

Strength of throat clearing |

Clarity of /h/ and /a/ during repetitive /ha/ |

Pitch range (slide up and down scale) |

Loudness range (say name soft, conversational, loud) |

Respiratory assessment |

Duration of phonation (prolong /o/ as long as you can) |

Duration of comfortable breath-hold needed to use swallow maneuvers (1 s, 3 s, 5 s, 10 s) |

Coordination of respiration and swallowing: Does the patient interrupt inhalation or exhalation to swallow? Does the patient inhale or exhale after the swallow? |

In the same way, the cloth can be used to test the patient’s chewing ability by placing the damp end of the 4-inch gauze roll onto the center of the patient’s tongue and asking the patient to lateralize to each side and chew on the roll of cloth. If the patient is unable to control the cloth in the mouth for mastication, and the cloth becomes “stuck” (for example, two-thirds of the way toward the teeth on one side), the clinician can simple pull the dry end of the gauze from the patient’s mouth, replace the damp end in the middle of the tongue, and the patient can return to the task. This eliminates the need to clean the patient’s mouth of food that may have gotten stuck, were food to be used in this task, and requires that the patient use all of the oromotor control needed for chewing. The risk of potentially losing food in the mouth and having it fall into the pharynx and into the open airway is eliminated. The task can be made more difficult by using chewing gum once the clinician is sure the patient will not accidentally swallow the gum. This becomes a therapy exercise then, as well as an evaluation strategy.

Respiratory Support

Respiratory support should be assessed by counting the rate of breaths per minute and by observing any obvious stressful or rapid respiration. Patients should be asked to hold their breath for a total of 1 second, then 3, 5, and 10 seconds, and the clinician should observe whether this behavior creates any respiratory distress. The duration of breath hold should be increased as tolerated by the patient. One important reason for assessing breath-hold ability is to determine whether the patient can tolerate swallow maneuvers, or other therapy procedures that increase the duration of the apneic or airway closure period during the swallow. Generally, patients need to be able to hold their breath for at least 5 seconds to use swallow maneuvers comfortably. The patient’s coordination of respiration and swallowing should be examined. Most often, normal adults interrupt the exhalatory phase of the respiratory cycle to swallow and return to exhalation after the swallow. 12 This coordination is thought to be a safer coordination than interrupting or returning to inhalation after the swallow, which might encourage inhalation of residue after the swallow.

Prolonged Phonation

Prolonged phonation on the vowel /o/ should also be examined in terms of both vocal quality and the respiratory control used. Is the patient able to take an easy inhalation followed by a slow drop of the chest and inward motion of the abdomen to produce a prolonged vowel on sustained phonation of at least 10 seconds?

Gag Reflex

The gag reflex should be tested, not to determine its presence or absence as an indicator of ability or inability to swallow, but rather to examine the pharyngeal wall motion as part of the motor response for the gag. The pharyngeal wall motion during the gag should be symmetrical. Any asymmetry may indicate a unilateral pharyngeal wall paresis. There is no evidence of a relationship between the presence and normalcy of a gag and the presence and normalcy of a swallow. 13, 14 The gag reflex is triggered from surface tactile sensory receptors by a noxious stimulus that does not belong in the posterior oral cavity or pharynx, such as vomit or reflux. The motor response of a gag is for the pharynx and larynx to elevate and close/contract to push out any foreign body. In contrast, the swallow is triggered from deeper proprioceptive receptors as well as surface receptors, and the motor response of a swallow is a coordinated set of muscle contractions designed to carry food from the mouth through the pharynx and into the esophagus, essentially the opposite of a gag motor response. In addition, several studies have shown that the gag reflex can be eliminated by topical anesthetic, whereas the swallow remains entirely intact. If the deeper proprioceptive receptors are anesthetized, however, then the swallow will be eliminated. Thus, there is no reason to hypothesize that the gag and swallow in any way predict each other, other than to say that if a patient sustains significant neurologic damage, it is quite likely that both the gag and the swallow will be affected because of the extent of damage. Despite the lack of relationship between gag and swallow, both neurologically and physiologically, many physicians learn in their residency that the gag reflex in some way is predictive of swallow normalcy. Case four emphasizes this point.

10.3.3 Case Study 4

A 53-year-old man was referred for a modified barium swallow because he had an asymmetrical uvula and an absent gag reflex. In discussing this test with the patient and taking a brief history prior to the X-ray study, the clinician determined that the patient had no swallowing complaints and had no nasality or any other indication of velopharyngeal insufficiency or incompetence for speech. Oral examination did reveal an asymmetrical uvula but good upward-backward motion of the soft palate and visible inward motion of the lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls. Because the patient insisted, the videofluoroscopic study was completed and showed an entirely normal oropharyngeal swallow. In this case, the patient had been referred because the physician thought that an absent gag reflex indicated a swallowing problem and, in combination with an asymmetrical uvula, might indicate neurologic disease. In the report of the radiographic study to the physician, the differences in the gag reflex and swallow were emphasized, as was the high incidence of absent gag in normal individuals. The physician indicated that he was extremely grateful for this information.

Laryngeal Function

Laryngeal function should also be assessed by the series of voluntary tasks listed in ▶ Table 10.1, with the clinician assessing vocal quality and respiratory support during each task. Increasing loudness and increasing phonation time require coordination between respiratory and phonatory control.

Throughout all of the oromotor testing, the clinician also assesses the patient’s general behavioral level, ability to discipline his or her own behavior and focus on the tasks, impulsiveness, and other cognitive and language characteristics that interact with swallow physiology to facilitate the eating situation. Successful eating requires functional swallowing (no aspiration and some manageable residue), behavioral control, and language ability. Two patients may exhibit the same swallow physiology, but the one with behavioral problems and an inability to focus on tasks will generally exhibit longer recovery to oral intake than the patient who is capable of focusing, following directions, and monitoring one’s own performance.

If the patient is taking oral nutrition, the clinician should observe the patient at bedside during a meal to identify the typical postures used, the placement of the food in the mouth, the patient’s general awareness of food and reaction to food, and the presence of any behavior that might indicate food entering the airway (aspiration), such as coughing, throat clearing, periods of difficulty breathing, gurgly voice, etc. 15 Also, an apraxia of swallow should be noted. Generally, apraxia of swallow is characterized by searching motions in the oral cavity as food is being placed there, or simply no motion in the oral cavity in response to placement of food there.

Once the clinician has collected data on oromotor control, the patient’s behavior and language levels, and any symptoms of an oropharyngeal dysphagia, the clinician may attempt some intervention strategies at the bedside. The difficulty, of course, is that with pharyngeal dysphagia, the effects of any treatment strategies, as well as the identification of the actual anatomical or physiologic abnormality causing the patient’s symptoms, cannot be accurately determined at the bedside. Therefore, the clinician may believe that a therapy procedure works because the patient doesn’t cough or clear any material from the airway, but in fact, food may be collecting in the pharyngeal recesses formed by the natural attachment of structures to each other, such as the piriform sinuses or the valleculae. The patient may appear to be “swallowing” when in fact food is simply resting in these recesses, waiting for a swallow, or may be left in these recesses after an inefficient swallow.

At this point, all of the data the clinician has collected from the patient’s medical chart and history, as well as from direct examination, combine to identify the patient’s risk level for a pharyngeal dysphagia and the need for a VFS or modified barium swallow study of the pharyngeal stage of swallowing. As a general guideline, if the patient has any of the behaviors or diagnoses listed in ▶ Table 10.2, the clinician should recommend a modified barium swallow or other physiologic assessment to directly examine pharyngeal physiology during swallows of various bolus types, as described below. Treatment for oral-stage problems can be initiated in parallel with conducting the VFS study of the pharyngeal stage of swallowing.

Diagnosis at Highest Risk for Pharyngeal Dysphagia | Symptoms Indicating High Risk for Pharyngeal Disorders |

Parkinson’s disease | Gurgly voice |

Motor neuron disease | History of pneumonia |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Difficulty managing secretions |

Postpolio syndrome | Increased secretions in chest |

Brainstem stroke | Coughing or throat clearing during eating |

Head and neck cancer patients treated with surgery/radiotherapy | Patient report of food “sticking” in throat |

Myasthenia gravis | |

Guillain-Barré syndrome | |

Multiple sclerosis (if complaining of swallow problems) | |

Dermatomyositis | |

Scleroderma | |

Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy | |

Myotonic dystrophy |

The bedside clinical assessment of oropharyngeal dysphagia is a screening test for the pharyngeal stage of swallowing, but not a definitive diagnostic test for the oral stages of swallowing in patients with neurologic lesions in the brainstem or below, that is, the final common path, and for patients with peripheral structural damage, such as surgery or radio-therapy for head and neck cancer, gunshot wounds, other trauma, etc. 16 For patients with cortical or subcortical neural damage, the effects on oral control may be different for speech and swallowing because these higher neural structures, although involved in both speech and swallowing, are utilized differently for the two functions. Performance on voluntary speech tasks may not reflect performance of the same structures during swallowing. 16

10.3.4 Other Bedside Screening Tests

The clinician may wish to introduce other screening tests at the bedside to gain further evidence of the potential for a pharyngeal-stage swallowing problem. These include the blue dye test in tracheostomized patients, cervical auscultation, and the videoendoscopic assessment of pharyngeal swallow known as the fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES). Each of these procedures defines symptoms of swallowing disorders.

Blue Dye Test

The blue dye test involves presenting blue-dyed foods to a patient with a tracheostomy and suctioning after each swallow attempt to identify the presence of any food in the airway below the larynx. 17, 18 This test has been found to have both a negative and positive error rate, that is, it misidentifies patients as aspirating who are not and misidentifies patients who are actually aspirating as not aspirating. There is no set protocol for this procedure. Generally, clinicians using it prefer to introduce thin liquids, thick liquids, pureed foods, and mechanical soft foods, all dyed blue, to distinguish the foods from bodily secretions. If the patient loses food out the tracheostomy during or after a swallow or for a period of time after eating, aspiration is indicated and the need for VFS or definitive diagnostic study is identified.

Cervical Auscultation

Cervical auscultation involves placing a stethoscope against the patient’s neck and listening to the sounds of swallow and respiration. 19, 20 The inhalatory and exhalatory phases of the respiratory cycle can generally be identified with auscultation. Also the clinician can define the phase of respiration during which the patient swallows. Unfortunately, the sounds of swallowing have not yet been completely identified so that the meaning of the sounds heard by the clinician during the swallow is undetermined. Also, we do not know if clinicians can detect normal from abnormal sounds. In any case, the outcome of auscultation is the identification of a patient’s risk for pharyngeal-stage dysphagia and its major symptom, aspiration. A definitive diagnostic procedure is needed to identify the exact nature of the dysphagia, to plan treatment, and to evaluate effects of treatment procedures.

Fiberoptic Endoscopic Examination of Swallowing

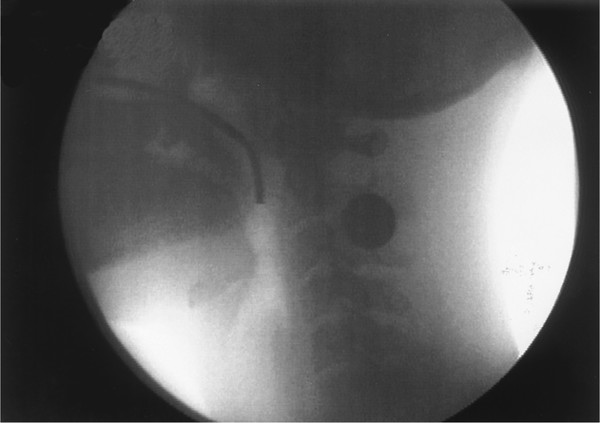

Fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES) involves nasal placement of a fiberoptic laryngoscope (generally 3.5-mm in diameter) so that the tip of the laryngoscope is positioned posterior to the uvula, as seen in ▶ Fig. 10.1. In this position, the endoscope visualizes the pharynx from above, including the valleculae, the airway entrance, and the posterior and lateral pharyngeal walls. 21, 22, 23 During the swallow, the oral stages are not visible. The bolus becomes visible as it comes over the base of the tongue and into the pharynx. When the pharyngeal swallow triggers and the pharyngeal motor response begins, laryngeal and pharyngeal elevation is partially visualized, followed by a period of “white out” when nothing can be seen as the pharynx closes around the endoscopic tube. When the swallow ends and the pharynx relaxes, the pharynx can be visualized again. Any residual food left in the pharynx can be seen. Thus, the swallow itself is not visualized. Instead, FEES examines the pharynx before and after the swallow. FEES can provide information on anatomical changes in the pharynx resulting from surgery or trauma, which can be helpful to the clinician trying to understand the patient’s altered anatomy. FEES can also be used to provide biofeedback for airway closure maneuvers described later, specifically the supraglottic and super-supraglottic swallow maneuvers.

Fig. 10.1 Lateral videofluorographic view of the oropharyngeal region showing the placement of the fiberoptic endoscope through the nose and over the soft palate, with the tip of the endoscope at the approximate level of the inferior tip of the uvula.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree