aRemainder of particle composition: protein and phospholipid.

Chol, cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); TG, triglyceride; VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Atherosclerosis and Lipoproteins

Nearly 90% of patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) have some form of dyslipidemia. Increased levels of LDL cholesterol, remnant lipoproteins, and Lp(a) as well as decreased levels of HDL cholesterol have all been associated with an increased risk of premature vascular disease.1,2

Clinical Dyslipoproteinemias

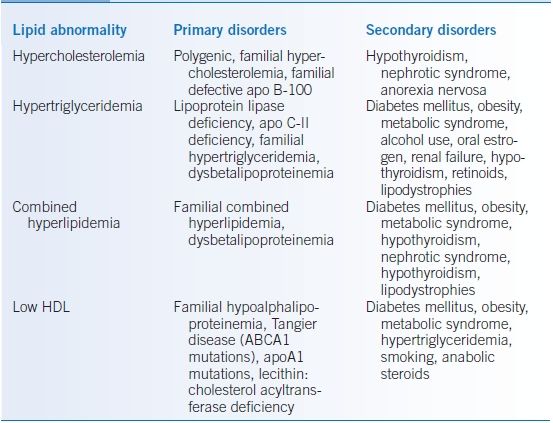

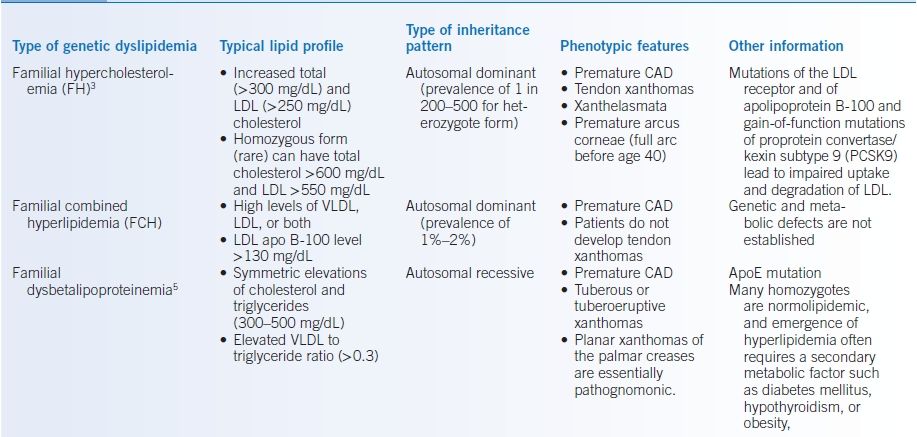

- Most dyslipidemias are multifactorial in etiology and reflect the effects of genetic influences coupled with diet, inactivity, smoking, alcohol use, and comorbid conditions such as obesity and diabetes mellitus (DM). Differential diagnosis of the major lipid abnormalities is summarized in Table 11-2. The major genetic dyslipoproteinemias are reviewed in Table 11-3.3–5

- Familial hypercholesterolemia and familial combined hyperlipidemia are disorders that contribute significantly to premature cardiovascular disease.

- Familial hypercholesterolemia is an underdiagnosed, autosomal codominant condition with a prevalence of 1 in 200 to 1 in 500 people that causes elevated LDL cholesterol levels from birth.6,7 It is associated with significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular disease when untreated.8

- Familial combined hyperlipidemia has a prevalence of 1% to 2% and typically presents in adulthood, although obesity and high dietary fat and sugar intake have led to increased presentation in childhood and adolescence.9

- Familial hypercholesterolemia is an underdiagnosed, autosomal codominant condition with a prevalence of 1 in 200 to 1 in 500 people that causes elevated LDL cholesterol levels from birth.6,7 It is associated with significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular disease when untreated.8

TABLE 11-2 Differential Diagnosis of Major Lipid Abnormalities

HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

TABLE 11-3 Review of Major Genetic Dyslipoproteinemias

CAD, coronary artery disease; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Standards of Care for Hyperlipidemia

LDL cholesterol–lowering therapy, particularly with hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (commonly referred to as statins), lowers the risk of CHD-related death, morbidity, and revascularization procedures in patients with (secondary prevention) or without (primary prevention) known CHD.10–17 Prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the primary goal of the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines. These guidelines address risk assessment, lifestyle modifications, evaluation and treatment of obesity, and evaluation and management of blood cholesterol.18–21

Diagnosis

Screening

- Screening for hypercholesterolemia should begin in all adults aged 20 years or older.18

- Screening is best performed with a lipid profile (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides) obtained after a 12-hour fast.

- If a fasting lipid panel cannot be obtained, total and HDL cholesterol should be measured. Total cholesterol ≥220 mg/dL may indicate a genetic or secondary cause. A fasting lipid panel is required if total cholesterol is ≥220 mg/dL or triglycerides are ≥500 mg/dL.

- If the patient does not have an indication for LDL-lowering therapy, screening can be performed every 4 to 6 years between ages 40 and 75.18

- Patients hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome or coronary revascularization should have a lipid panel obtained within 24 hours of admission if lipid levels are unknown.

- Individuals with hyperlipidemia should be evaluated for potential secondary causes, including hypothyroidism, DM, obstructive liver disease, chronic renal disease, nephrotic syndrome, or medications such as estrogens, progestins, anabolic steroids/androgens, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, retinoids, atypical antipsychotics, and antiretrovirals (particularly protease inhibitors).

Risk Assessment

- The 2013 guidelines identify four groups in whom the benefits of LDL-lowering therapy with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) clearly outweigh the risks:21

- Patients with clinical ASCVD

- Patients with LDL ≥190 mg/dL

- Patients with DM aged 40 to 75 with LDL between 70 and 189 mg/dL

- Patients with a calculated ASCVD risk ≥7.5%

- Patients with clinical ASCVD

- For patients without clinical ASCVD or an LDL ≥190 mg/dL, the guidelines advise calculating a patient’s risk for ASCVD based on age, sex, ethnicity, total and HDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure (treated or untreated), presence of DM, and current smoking status.18

- The ACC/AHA risk calculator is available at http://my.americanheart.org/cvriskcalculator (last accessed December 22, 2014).

- For patients of ethnicities other than African American or non-Hispanic White, risk could not be as well assessed. Use of the non-Hispanic White risk calculation is suggested, with the understanding that risk may be lower than calculated in East Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans and higher in American Indians and South Asians.

- A 10-year risk should be calculated beginning at age 40 in patients without ASCVD or LDL ≥190 mg/dL.

- Lifetime risk may be calculated in patients aged 20 through 39, and patients aged 40 through 59 with a 10-year risk under 7.5%, to inform decisions regarding lifestyle modification.

- For patients of ethnicities other than African American or non-Hispanic White, risk could not be as well assessed. Use of the non-Hispanic White risk calculation is suggested, with the understanding that risk may be lower than calculated in East Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans and higher in American Indians and South Asians.

TREATMENT

- The 2013 guidelines recognize lifestyle factors, including diet and weight management as an important component of risk reduction for all patients.19,20

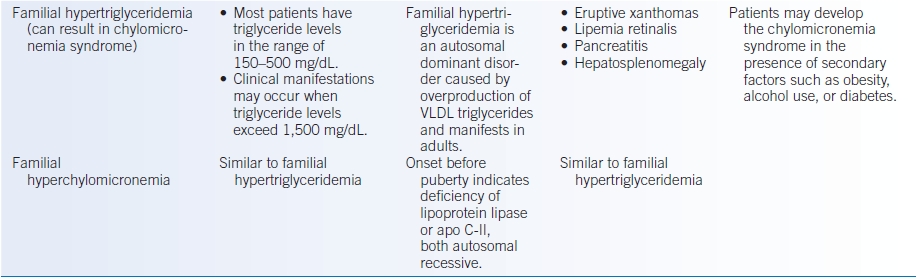

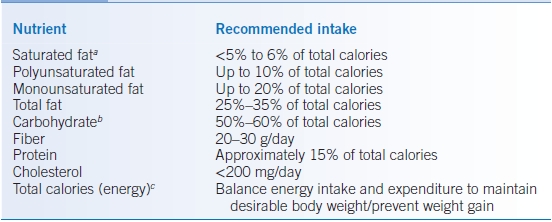

- Patients should be advised to adopt a diet that is high in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, lean meat, low-fat dairy, legumes, and nuts, with lower intake of red meat, saturated and trans fats, sweets, and sugary beverages. Saturated fat should comprise no more than 5% to 6% of total calories (Table 11-4).19

- Physical activity, including aerobic and resistance exercise, is recommended in all patients.19

- For all obese patients (BMI ≥ 30), or overweight patients (BMI ≥ 25) who have additional risk factors, sustained weight loss of 3% to 5% or greater reduces ASCVD risk.20

- Consultation with a registered dietitian may be helpful to plan, start, and maintain a saturated fat–restricted and weight loss–promoting diet.

- Prior to the start of treatment, there should be a risk discussion between the patient and the clinician. Topics for discussion include the following:

- Potential for ASCVD risk reduction benefits

- Potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions

- Heart-healthy lifestyle and management of other risk factors

- Patient preferences

- Potential for ASCVD risk reduction benefits

TABLE 11-4 Nutrient Composition of the Therapeutic Lifestyle Change (TLC) Diet

aTrans fatty acids are another low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-raising fat that should be kept at a low intake.

bCarbohydrate should be derived predominantly from foods rich in complex carbohydrates, including grains (especially whole grains), fruits, and vegetables.

cDaily energy expenditure should include at least moderate physical activity (contributing approximately 200 Kcal/day).

Data from Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:S76–S99.

Clinical Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

- Clinical ASCVD includes acute coronary syndromes, history of myocardial infarction, stable angina, arterial revascularization (coronary or otherwise), stroke, transient ischemic attack, or atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease.

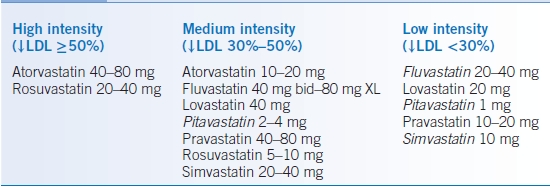

- Secondary prevention is an indication for high-intensity statin therapy (Table 11-5), which has been shown to reduce events more than moderate-intensity statin therapy.

- If high-dose statin therapy is contraindicated or poorly tolerated, or there are significant risks to high-intensity therapy (including age >75 years), moderate-intensity therapy is an option.

TABLE 11-5 Statin Therapy Regimens by Intensity

Italicized doses have not been studied in RCTs but achieve this level of LDL reduction in clinical use.

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; ↓, decreased.

Data from Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:S1–S45.

LDL ≥ 190 mg/dL

- These individuals have elevated lifetime risk because of long-term exposure to very high LDL-C levels, and the risk calculator does not account for this.

- LDL-C should be reduced by at least 50%, primarily with high-intensity statin therapy (Table 11-5). If high-intensity therapy is not tolerated, maximum tolerated intensity should be used.

- Even high-intensity statin therapy may not be sufficient to reduce LDL-C by 50%, and nonstatin therapies are often required to achieve this goal.22

- LDL apheresis is an optional therapy in patients with homozygous FH and those with severe heterozygous FH with insufficient response to medication. Lomitapide, a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor, and mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B antisense oligonucleotide, are new medications indicated for the treatment of patients with homozygous FH.7

- As hyperlipidemia of this degree is often genetically determined, discuss screening of other family members (including children) to identify candidates for treatment. In addition, screen for and treat secondary causes of hyperlipidemia.6

Patients with Diabetes, Aged 40 to 75, LDL 70 to 189

- Using the AHA/ACC risk calculator, calculate the 10-year risk of an ASCVD event in these patients (categories, ≥7.5%, or ≤7.5%).

- If the risk is ≥7.5%, consider high-intensity statin therapy (Table 11-5).

- Otherwise, these patients have an indication for moderate-intensity statin therapy.

Patients without Diabetes, Aged 40 to 75, LDL 70 to 189

- Using the AHA/ACC risk calculator, calculate 10-year risk of an ASCVD event in these patients (categories, ≥7.5%, between 5.0% and 7.5%, and ≤5.0%).

- A 10-year risk ≥7.5% is an indication for moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy. The decision between moderate- and high-intensity therapy should be made with the patient based on anticipated, individualized risks and benefits.

- A 10-year risk between 5% and 7.5% is reasonable for moderate-intensity statin therapy.

Other Patient Populations

- Some patients not described above may still benefit from statin therapy—if the decision on treatment is unclear, the guidelines offer assessment of family history, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, or arterial-brachial index (ABI) as options to further define risk.18,21

- A family history of premature ASCVD is defined as an event in a first-degree male relative before age 55 or in a first-degree female relative before age 65.

- Higher risk is also indicated by an hs-CRP ≥2 mg/L; CAC ≥300 Agatston units or ≥75th percentile for age, sex, and ethnicity; or ABI ≤0.9.

- The role of other biomarkers in risk assessment remains uncertain.

- Depending on patient preference and assessment of risks and benefits, lower LDL-C levels can be considered for treatment (particularly LDL ≥160 mg/dL).

- Patients with diabetes younger than 40 or older than 75 are reasonable candidates for statin therapy based on individual evaluation.

- A family history of premature ASCVD is defined as an event in a first-degree male relative before age 55 or in a first-degree female relative before age 65.

- Use of statin therapy should be individualized for patients older than 75. In RCTs, patients older than 75 continued to have benefit from statin therapy, particularly for secondary prevention.13,23 In addition, many ASCVD events occur in this age group, and patients without other comorbidities may benefit substantially from cardiovascular risk reduction.

- No official recommendation was made in the guidelines regarding initiation or continuation of statin therapy in patients on maintenance hemodialysis or with NYHA class II to IV ischemic systolic heart failure. Evidence from RCTs has not shown a benefit from statin therapy in these subpopulations.21

Hypertriglyceridemia

- Hypertriglyceridemia may be an independent cardiovascular risk factor.24–26

- Hypertriglyceridemia is often observed in the metabolic syndrome, and there are many potential etiologies for hypertriglyceridemia, including obesity, DM, renal insufficiency, genetic dyslipidemias, and therapy with oral estrogen, glucocorticoids, β-blockers, tamoxifen, cyclosporine, antiretrovirals, and retinoids.27

- The classification of serum triglyceride levels is as follows: Normal: <150 mg/dL. Borderline-high: 150 to 199 mg/dL. High: 200 to 499 mg/dL. Very high: ≥500 mg/dL.26 The Endocrine Society has added two further categories: severe: 1,000 to 1,999 mg/dL (greatly increases the risk of pancreatitis) and very severe: ≥2,000 mg/dL.9

- Treatment of hypertriglyceridemia depends on the degree of severity.

- For patients with very high triglyceride levels, triglyceride reduction through a very-low-fat diet (≤15% of calories), exercise, weight loss, and drugs (fibrates, niacin, omega-3 fatty acids) is the primary goal of therapy to prevent acute pancreatitis.

- When patients have a lesser degree of hypertriglyceridemia, controlling the LDL cholesterol level is the primary aim of initial therapy. Lifestyle changes are indicated to lower triglyceride levels.9

- For patients with very high triglyceride levels, triglyceride reduction through a very-low-fat diet (≤15% of calories), exercise, weight loss, and drugs (fibrates, niacin, omega-3 fatty acids) is the primary goal of therapy to prevent acute pancreatitis.

Low HDL Cholesterol

- Low HDL cholesterol is an independent ASCVD risk factor that is identified as a non-LDL cholesterol risk and is included as a component of the ACC/AHA scoring algorithm.18

- Etiologies for low HDL cholesterol include genetic conditions, physical inactivity, obesity, insulin resistance, DM, hypertriglyceridemia, cigarette smoking, high (>60% calories) carbohydrate diets, and certain medications (β-blockers, anabolic steroids/androgens, progestins).

- Because therapeutic interventions for low HDL cholesterol are of limited efficacy, the guidelines recommend considering low HDL as a component of overall risk, rather than targeting low HDL as a specific therapeutic target.

- There are no clinical trial data showing a benefit of pharmacologic methods of elevating HDL cholesterol.

Starting and Monitoring Therapy

- Before starting therapy, guidelines recommend checking alanine aminotransferase (ALT), HgbA1c (if diabetes status is unknown), labs for secondary causes (if indicated), and creatine kinase (CK) if indicated.

- Evaluate for patient characteristics increasing the risk of adverse events from statins: impaired hepatic and renal function, history of statin intolerance, history of muscle disorders, unexplained elevations of ALT >3× the upper limit of normal, drugs affecting statin metabolism, Asian ethnicity, and age >75 years.21

- A repeat fasting lipid panel is indicated 4 to 12 weeks after starting therapy to assess adherence, with reassessment every 3 to 12 months as indicated.

- In contrast to previous guidelines, therapeutic targets are not recommended, as specific targets and a treat to target strategy have not been evaluated in RCTs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree