Drugs Used to Affect the Autonomic and Somatic Nervous Systems

Overview

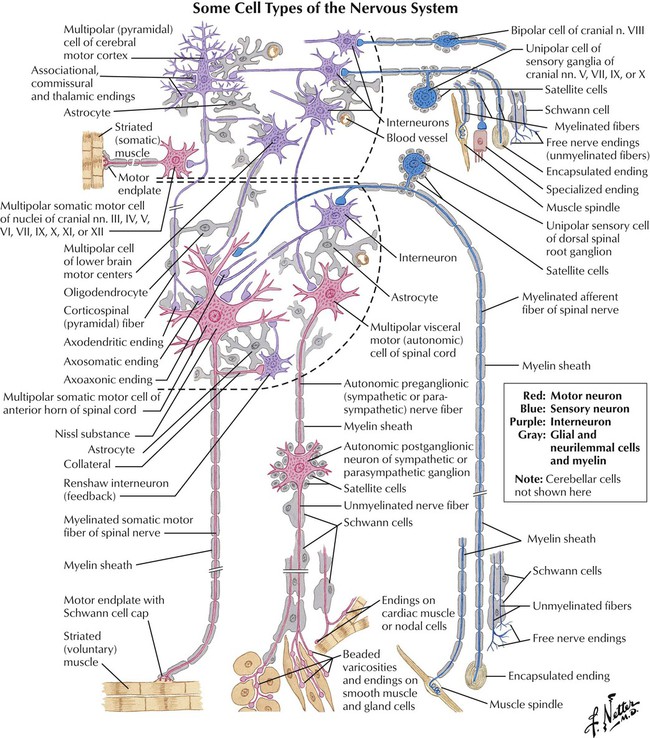

The actions of many drugs can be understood as the modulation of the nervous system’s control of physiologic processes. The CNS and PNS communicate via afferent and efferent neurons. As a result of this anatomical organization, drugs can affect sensory input (eg, local anesthetics for pain), skeletal muscle activity (eg, muscle relaxants for surgery), or autonomic output (eg, drugs that act on blood vessels or the heart to reduce high blood pressure).

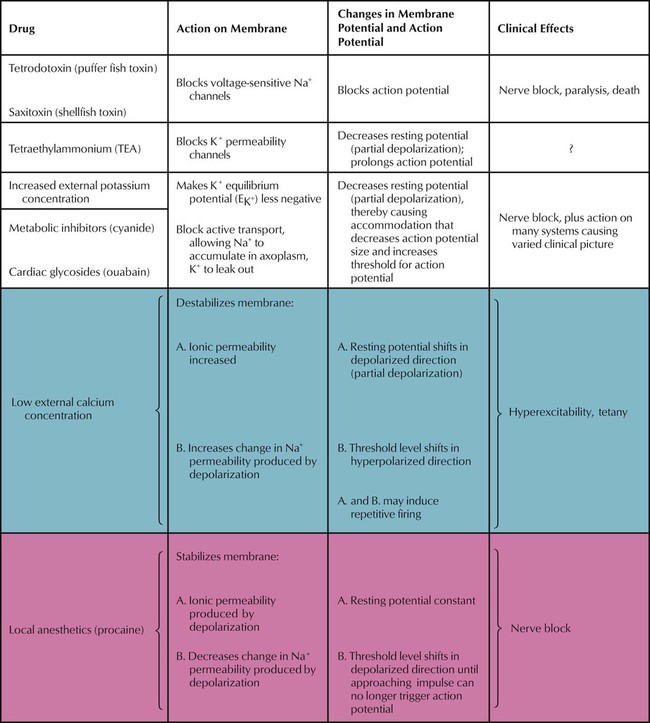

Efficient and effective transmission of neuronal action potentials relies on the unequal distribution of positive (primarily Na+ and K+) and negative (primarily Cl−) ions across the axonal membrane. Selective, voltage-sensitive permeability of the membrane to these ions establishes the unequal distribution of the ions according to the Nernst equation and gives rise to a resting transmembrane potential difference. Drugs that alter the ion flux affect the resting transmembrane potential difference. The larger this difference, the further the neuron is from its firing threshold and the less likely that it will fire (ie, initiate an action potential). The smaller the transmembrane potential difference, the more likely it is that the neuron will reach this threshold and fire.

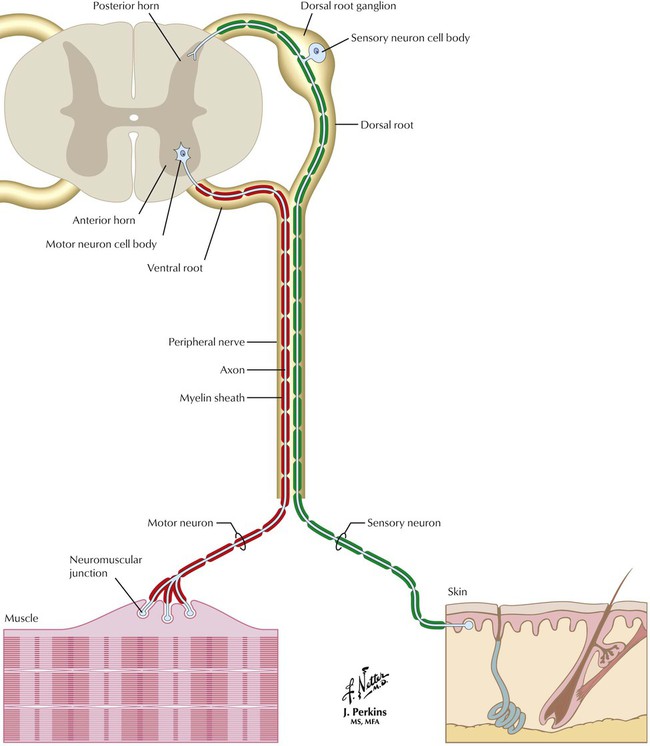

Spinal nerve pairs enter and exit along segmented caudal, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral portions of the spinal cord and distribute throughout the body. Somatic afferent neurons transmit sensory information about normal status (eg, proprioception) or pathologic states (eg, heat and mechanical damage) to the spinal cord and brain. Efferent neurons carry motor signals from the spinal cord and brain to the somatic (striated or skeletal muscles: effectors) and autonomic (smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, glands) divisions of the PNS. Drugs can selectively modulate the activity of afferent or efferent pathways: those that excite afferent nociceptive neurons produce pain; those that inhibit afferent nociceptive neurons are analgesic. Those that excite efferent, or neuromuscular, junctions produce tetanus; those that inhibit these junctions cause paralysis.

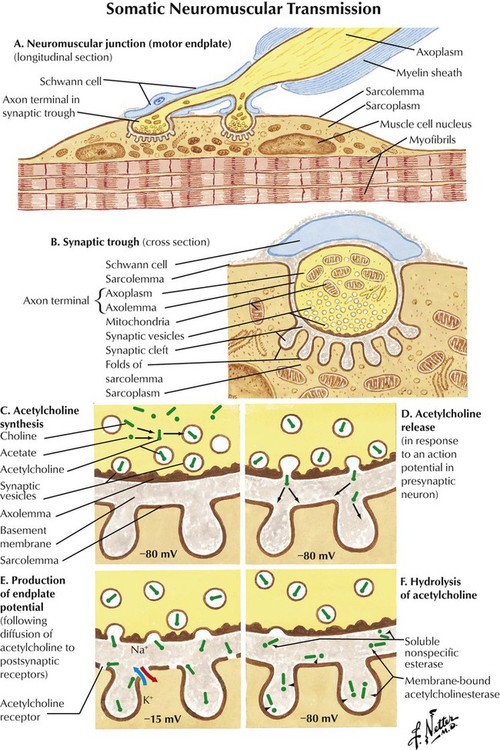

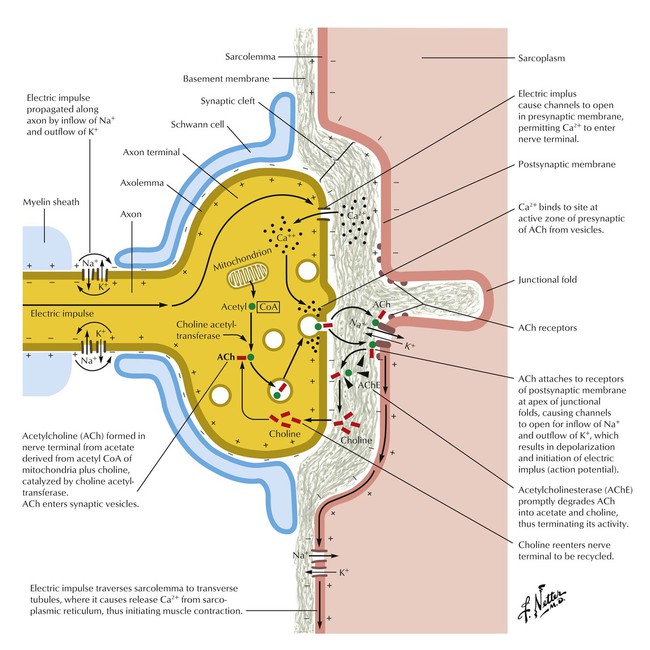

Neurons innervate skeletal muscles at the neuromuscular junction (A). The axon-muscle interface forms at a synaptic trough, which has extensive foldings that increase the surface area of exposure to a neurotransmitter (B). ACh, the neurotransmitter at neuromuscular junctions, is synthesized in the presynaptic neuron from mitochondrial acetyl-CoA and extracellular choline via an enzyme-catalyzed reaction. ACh is stored in presynaptic vesicles (C) until release in response to an action potential in the presynaptic neuron (D), a Ca2+-dependent process. ACh diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds reversibly to specific receptor sites on the postsynaptic membrane. Ion flux then increases and the postsynaptic membrane depolarizes (E), which triggers an action potential that leads to muscle contraction. Released ACh is eliminated from the synapse by cholinesterase action (F).

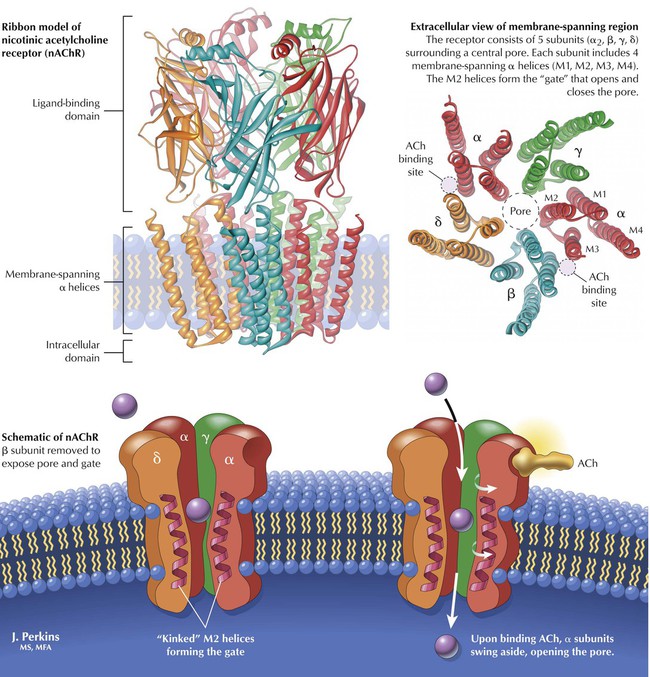

Drugs that block cholinesterases prolong the ACh residency time in the synapse and enhance the effect of ACh. Receptors at neuromuscular junctions are termed nicotinic cholinergic receptors (nAChRs) because nicotine is a relatively selective agonist at these sites. In an nAChR, 5 subunits (α2, β, γ, σ) form a cluster around a central cation-selective pore. Two ACh-binding sites are in the extracellular part of the receptor between α and the other subunits. When ACh binds to the sites, the receptor conformation changes: α subunits swing out, and the channel opens. Charged amino acids lining the pore select ions that can pass into the cell.

As Loewi demonstrated in the 1920s, a gap (synapse) exists between an ANS neuron’s axon terminal and the adjacent neuron or effector cell. Information is transmitted across this gap via chemical transmitters (neurotransmission). Neurotransmitters are commonly stored in presynaptic vesicles; arrival of an action potential stimulates a Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release into the synapse. The neurotransmitter crosses the gap and binds to highly selective receptor molecules on the postsynaptic cell, thereby modifying the activity of the postsynaptic cell. Neurotransmission provides fidelity of signal transmission. ANS neurotransmitters are simple organic molecules, and exogenous chemicals (drugs) can modify (mimic or antagonize) the action of the endogenous ANS neurotransmitters.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree