Drugs Used to Affect Renal Function

Overview

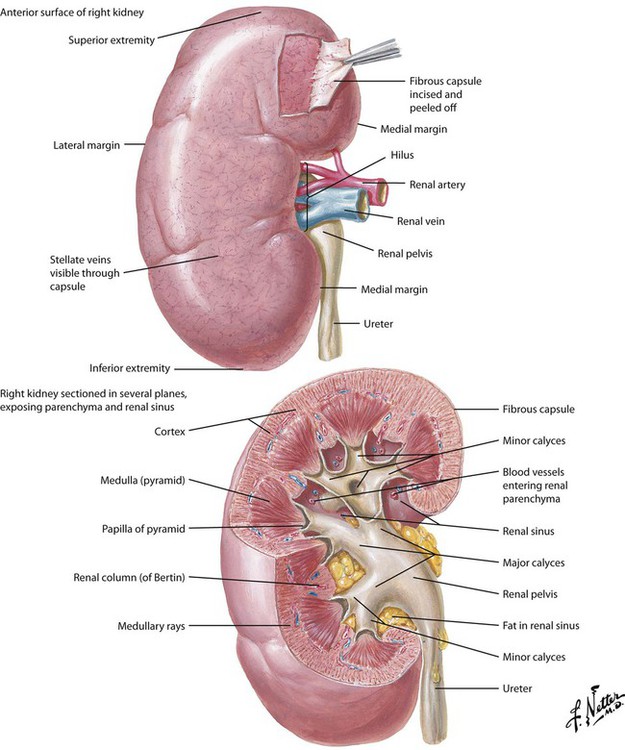

The kidneys are a pair of specialized, retroperitoneal organs located at the level between the lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae. Each kidney is reddish brown and has a characteristic shape: a convex lateral edge and concave medial border with a marked depression or notch termed the hilus. Each adult kidney is approximately 11 cm long, 2.5 cm thick, and 5 cm wide and weighs 120 to 170 g. Kidneys contribute to several important processes, including regulation of fluid volume; regulation of electrolyte balance; excretion of metabolic wastes; and elimination of toxic compounds, drugs, and their metabolites. It also acts as an endocrine organ. Each kidney is divided into a cortex and a medulla, both parts containing nephrons (approximately 1.25 million per kidney). The fluid that exits a nephron flows out the papilla of a pyramid (8-15 per medulla), enters a minor calyx, joins effluent of other minor calyces in the major calyx, and is eliminated as urine through the ureter.

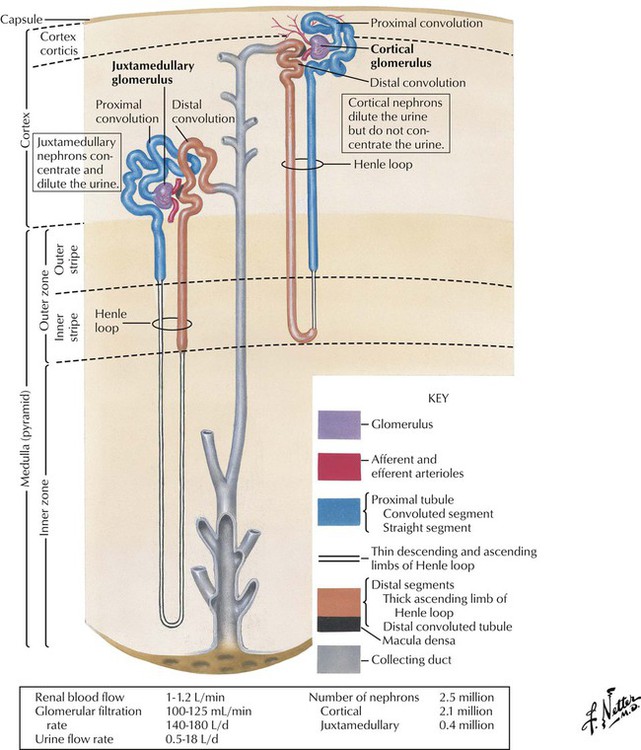

Each kidney contains approximately 1 to 3 million tubular nephrons (Greek nephros, meaning kidney). A nephron originates in the glomerular apparatus. The part adjoining this corpuscle is termed the proximal convoluted tubule because of its tortuous course that remains close to its point of origin. The tubule then straightens in the direction of the center of the kidney and forms the Henle loop, by making a hairpin turn and returning to the vascular pole of its parent renal corpuscle. The loop extends to the distal convoluted tubule and then to the collecting tubule. Collecting tubules unite to form larger collecting ducts. Most nephrons originate in the kidney cortex, are short, and extend only to the outer medullary zone. Other nephrons originate close to the medullary level (juxtamedullary glomeruli) and extend deep into the medulla, almost as far as the papilla. Each part of the nephron acts in physiologic processes that affect or are affected by metabolism of drug molecules (or their metabolites).

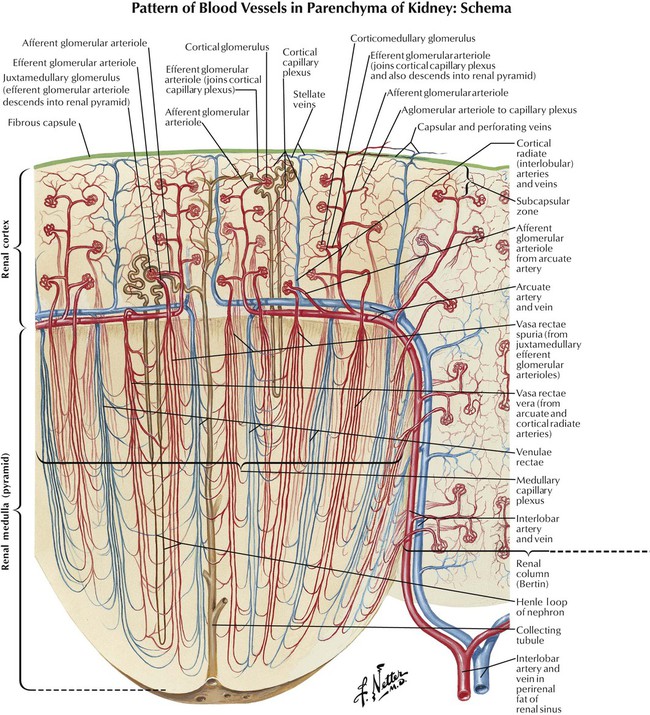

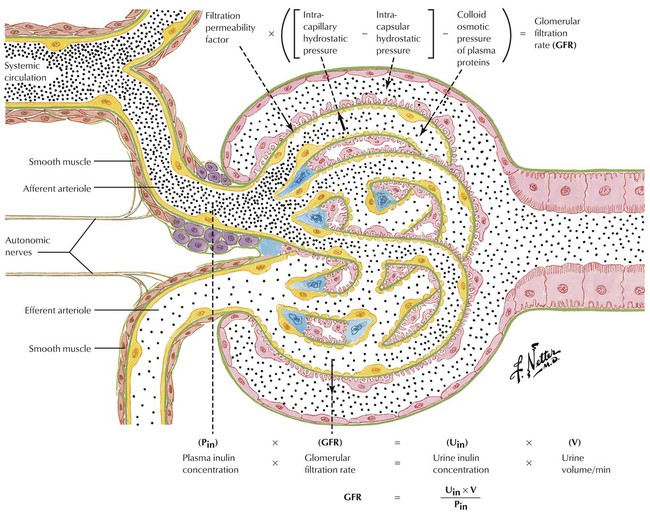

Critical to multiple kidney functions is close association of nephrons with blood vessels, in that water and other substances pass from nephron to blood and vice versa. Kidneys have a great influence on volume and composition of plasma and urine, so the architecture of renal vasculature reflects functions other than tissue oxygenation. In the outer renal cortex, each afferent arteriole enters a glomerulus, divides, forms a capillary network, becomes an efferent arteriole, and exits the glomerulus. Neurotransmitters, drugs, and environmental factors that relax the afferent arteriole or constrict the efferent arteriole increase the GFR; those that constrict the afferent arteriole or relax the efferent arteriole reduce the GFR. Blood vessels surround and outnumber tubular segments of each nephron and form a peritubular network of capillaries that allows exchange of water, electrolytes, and other substances. This exchange is the target for actions of many drugs, especially diuretics.

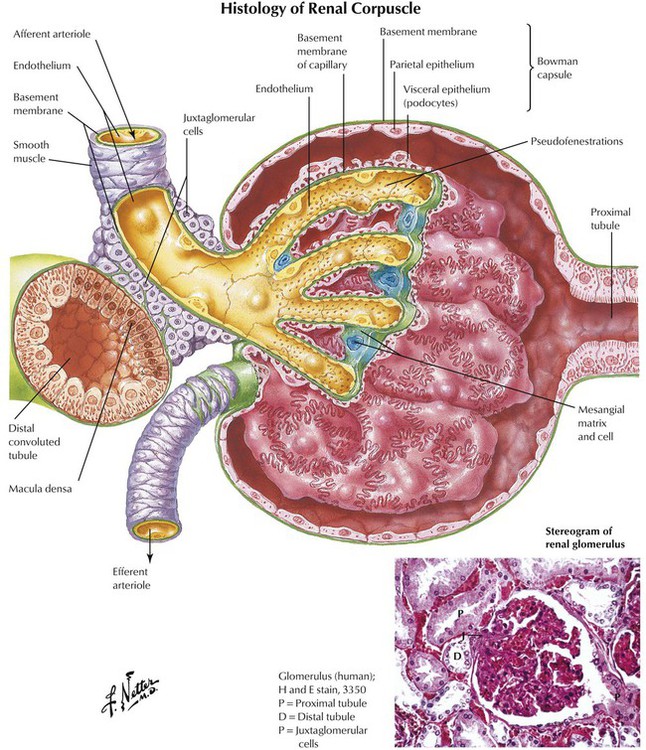

The glomerulus is an important interface between afferent arteriolar blood flow and the nephron. The glomerulus filters plasma, and the fluid, minus cells, enters the nephron as an ultrafiltrate. The glomerulus is also a barrier to molecules larger than approximately 5 kd (eg, plasma proteins). Thus, plasma proteins and drug molecules bound to them do not pass into nephrons of a healthy kidney; only smaller free drug or metabolite molecules do so. However, damaged glomeruli allow passage of plasma proteins, and the presence of these proteins in the urine indicates a renal disorder. In renal disease, drugs enter the nephron and are excreted at a rate greater than normal, which is noted as a shorter plasma half-life of drugs (or metabolites). Hormones and hormone-mimetic drugs that alter the GFR include angiotensin II (constricts afferent arterioles and thereby reduces the GFR) and atrial natriuretic peptide and prostaglandin E2 (dilate afferent arterioles and thus increase it).

The GFR is an important characteristic of kidney functioning and an important variable in elimination of drugs and their metabolites. In general, the greater the GFR is, the greater the rate of elimination is. The GFR can be measured noninvasively by determining the rate at which a substance is removed from plasma (or appears in urine), which requires the use of a substance that is freely filtered by the glomerulus and is neither reabsorbed nor secreted within the nephron. These criteria are fulfilled by the 5-kd fructose polysaccharide inulin. For the assay, after a uniform blood level of inulin is established, measurement of the concentration of inulin in plasma (Pin), the concentration of inulin in urine (Uin), and urine flow rate (V) yields the GFR from the equation: GFR = (V × Uin)/Pin. The GFR of a healthy adult kidney is approximately 120 mL/min. Decreased clearance, which is common in the elderly, usually results in slower drug elimination and requires an appropriate dosage adjustment.

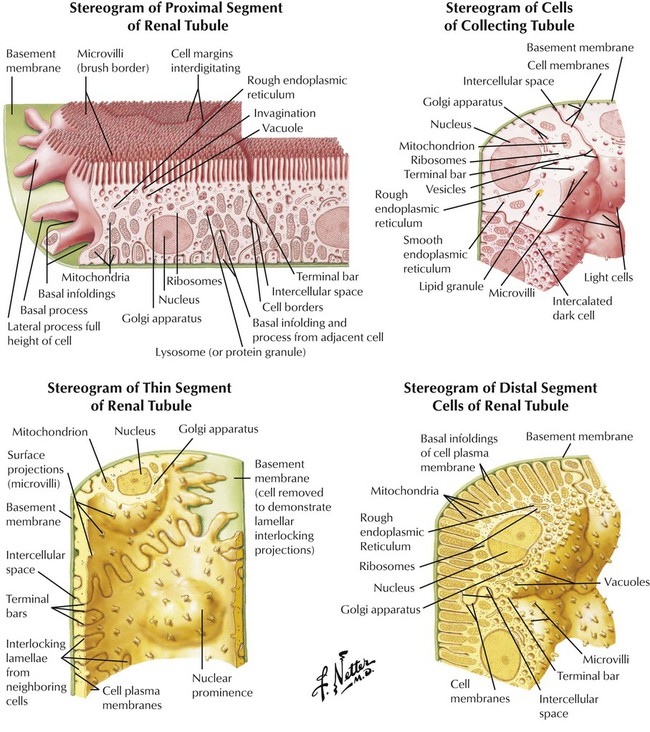

The structure and function of tubular segments are important for understanding drug effects on the kidney. The proximal portion and thick segment of the descending limb have a similar structure (slight variation in cell size and shape). Tight junctions between cells prevent escape of material in the tubular lumen. Proximal segment cells act to reabsorb water and other substances. The proximal segment’s brush border is replaced in the thin tubular segment by fewer short microvilli. Permeability to water and position of descending and ascending limbs of the Henle loop create a countercurrent multiplier for urine concentration. The distal segment of the nephron consists of the thick ascending limb of the Henle loop and the distal convoluted tubule. The ultrastructure and large surface area of the distal segment serve the energy requirements of active Na+ transport from luminal fluid, formation of ammonia, and urine acidification. Drug action in each segment alters kidney function in specific ways.

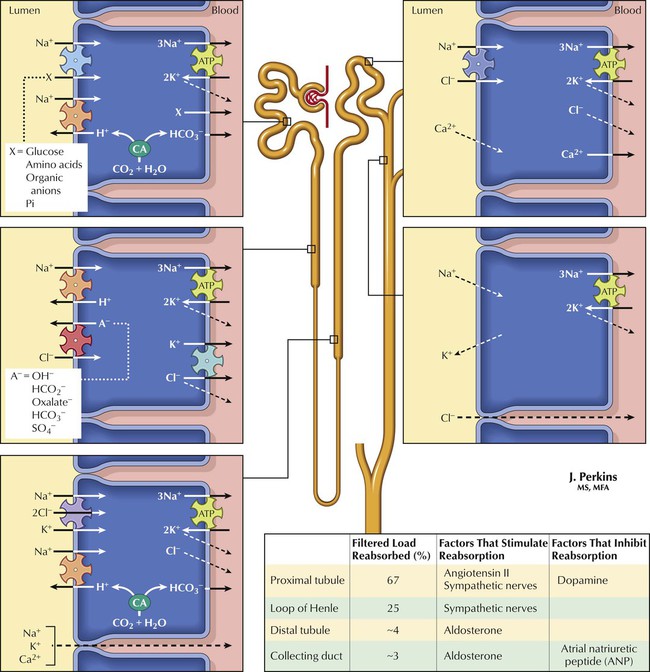

More than 99% of glomerular ultrafiltrate is reabsorbed from the tubular lumen. The kidney is thus more an organ of retention than of elimination. The driving factor for water and Na+ reabsorption in the nephron is active Na+ transport. Drugs affecting Na+ transport can alter urine flow and composition. Na+ reabsorption occurs against concentration and electrical potential gradients (the lumen is electrically negative compared with peritubular fluid) and is an active process requiring energy (supplied by ATP). The active uptake mechanism (pump) for Na+ involves a cotransporter that exchanges Na+ for K+, an important factor for drugs that affect Na+ transport. Cl− and other ions move by cotransport with Na+ or other ions or by passive diffusion. The osmotic gradient (established by ion transport) drives water out of the lumen. Hormones and drugs that decrease ion transport or the osmotic gradient reduce ion and water reabsorption and thus increase urine flow (diuresis) and ion content.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree