Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to drugs used in common mental health problems. The chapter examines three key areas of mental health intervention:

- anxiety;

- depression;

- psychosis.

Mental health issues extend into all aspects of nursing and an appreciation of the range of medications and how they work is essential for today’s nurses. One in four adults in the UK experience at least one diagnosable mental health problem in any one year, and one in six experiences this at any given time (Office for National Statistics 2001). It is estimated that approximately 450 million people worldwide have a mental health problem (World Health Organization 2001).

Anxiety

Anxiety is a fairly common, normal and usually self-limiting emotion, with which we are all familiar. For some people however, feelings of anxiety can be intolerable and can become disabling. This level of anxiety is considered to be pathological and requires prompt diagnosis and active treatment to help the sufferer regain and maintain their previously normal lifestyle. At this level, anxiety can manifest with wide and varied symptoms, both physical and psychological.

Anxiety is not simply one illness but a group of disorders characterized by psychological symptoms such as diffuse, unpleasant and vague feelings of apprehension, often accompanied by physical symptoms of autonomic arousal such as palpitations, light-headedness, perspiration, ‘butterflies’ and, in some patients, restlessness.

There are six main classifications of anxiety disorders:

1. panic disorder;

2. social phobia;

3. generalized anxiety disorder;

4. obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD);

5. post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD);

6. mixed anxiety and depressive disorder.

An understanding of the physiological mechanisms thought to be involved in the development of pathological anxiety is vital to ensure appropriate treatment of anxiety disorders. First it is important to understand that two brain systems appear to be involved in the generation of anxiety.

The defence system

The defence system controls our responses to danger. It receives stimuli related to the threat of danger and the brain interprets these stimuli and responds as required. The defence system is responsible for the so-called ‘fear, fight or flight’ responses. It can be a protective mechanism, whereby we can respond to threats or perceived threats and prepare the body to defend itself or to flee from the danger. It can also be activated by things which are not real threats, but are perceived as real by the anxiety sufferer and can become pathological.

The behavioural inhibition system

This system prevents a person from getting into danger and is responsible for avoidance behaviour. It is also involved in learning not to do dangerous things, therefore allowing future avoidance of anxiety-provoking situations. This can lead to anxiety sufferers withdrawing from real life situations because of the fear of being placed in danger, leading to agoraphobia, claustrophobia and social isolation.

Neurotransmitters in anxiety

The brain is a complex organ and with respect to anxiety many different neurotransmitters are involved. These include the following monoamines:

- noradrenaline (NA);

- 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) or serotonin;

- gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

The exact role these neurotransmitters play in anxiety is not fully elucidated, but using drugs that act on these systems can be beneficial in the management of anxiety.

Medicine management of anxiety

Although there is much commonality within the various anxiety disorders, it would be unwise to try to treat them all in the same way as they have important differences which necessitate variances in treatment. Anxiety management can be broken down into the following categories:

- non-pharmacological: psychological;

- pharmacological: single and combined psychotropic and non-psychotropic treatments;

- combinations of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments;

- surgical.

In reality the mainstay of anxiety treatment is pharmacological. Anxiolytic treatment should ideally be effective and quick-acting for rapid relief from the disabling symptoms. The treatment should not be too sedative as this can be as detrimental as the anxiety itself. This is achievable in the current pharmacological climate, but can often come at a price. The following drugs have all been used at one time to treat the symptoms of anxiety; many are still in use today:

- barbiturates;

- benzodiazepines;

- beta blockers;

- azaspirodecanediones;

- antipsychotics;

- antidepressants.

Barbiturates

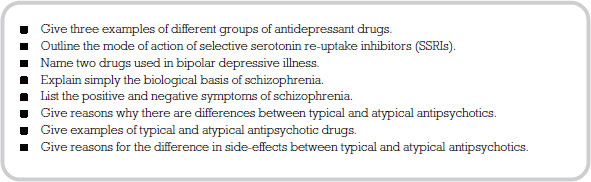

Barbiturates are potentiators of the GABA-A receptor which has a pentameric structure. It has five sub-units which surround an ion channel which conducts chloride (Cl-) ions (see Figure 8.1). It is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and central nervous system. Therefore potentiation of an inhibitory transmitter channel leads to increased inhibition, or reduced activity at the receptors the chloride ion acts on. This causes a ‘dampening down’ effect for all neuronal activity. When the Cl- ion channel is opened by GABA, the barbiturate drug molecule can enter the channel and causes it to remain open for a longer period of time than GABA alone would. This allows for more chloride from outside the neurone to enter it, so reducing the chance of an action potential being generated. This means that the barbiturate drugs cause a potentiation of GABA transmission and a reduction in neuronal activity.

There are downsides to using barbiturate drugs such as amobarbital (formerly amylobarbitone). They have a narrow therapeutic index, which means that the blood level of the drug needed for a beneficial effect is very close to the blood level which is toxic. This in turn means that it is easy to take too little and have no drug effect, or too much and reach toxicity. They also have addictive properties and patients can easily become dependent on them. They can also cause problems if taken with alcohol as it can increase their effects. For this reason they are very rarely used in anxiety management in modern times.

Benzodiazepines

For many years, the commonest and first-line pharmacological treatment for anxiety disorders was the prescription of a benzodiazepine drug. More recently this approach has changed with increased knowledge of the addictive and dependence problems and the abuse potential associated with benzodiazepines such as Diazepam and Temazepam. The use of these drugs has been related to significant long-term problems. The CSM issued the following advice which can be found in the BNF (2008: 55):

Benzodiazepines are indicated for the short-term relief (2–4 weeks only) of anxiety that is severe, disabling or subjecting the patient to unacceptable distress, occurring alone or in association with insomnia or short-term psychosomatic, organic or psychotic illness. The use of benzodiazepines to treat short-term ‘mild’ anxiety is inappropriate and unsuitable . . . benzodiazepines should be used to treat insomnia only when it is severe, disabling, or subjecting the individual to extreme distress.

All things considered however, benzodiazepines are still one of the most effective treatments for acute, transient anxiety. Like barbiturates, these drugs potentiate the effects of GABA but do so by a different mechanism. They bind to a specific benzodiazepine binding site (or receptor) which is situated on one of the sub-units of the GABA-A receptor. Their mechanism of action is to increase the affinity of GABA which leads to an increased ability and frequency of GABA to open the Cl- channel. Unlike barbiturates, benzodiazepines need GABA to be present all the time the channel is open, not just at activation, for them to have their effect. This makes them safer than barbiturates because they have a wider therapeutic index and less chance of toxicity and accidental overdose.

For use in anxiety, doses tend to be low, with higher doses being reserved for use in insomnia. This means that the side-effect of sedation should occur at a lower incidence although for some people drowsiness is a problem.

Another major side-effect of benzodiazepines is respiratory depression, and this should be monitored on initiation of therapy.

Beta-adrenergic blockers

These drugs are used not to treat the central nervous system transmitters thought to be involved in anxiety, but to treat the physical symptoms that are often manifest in anxiety such as palpitations, tremors, sweating and shortness of breath. They will not affect the psychological aspects of anxiety, so the patient will still feel anxious.

There are many beta-blocking drugs, but only propranolol and oxprenolol are licensed for use in the management of anxiety. The use of these drugs may help people with mild anxiety to function in situations where before their symptoms would have proved problematic.

Azaspirodecanediones

Buspirone is the only drug in its class available for the treatment and management of anxiety symptoms. Its mechanism of action is not fully elucidated but it is known to affect the serotonergic receptors, inhibiting serotonergic transmission. This effect develops quickly but the anxiolytic effect does not typically occur for two to three weeks. This can be problematic in anxiety treatment as patients often cannot tolerate the delayed onset of action.

Buspirone is not associated with addiction or dependence, but is only licensed for short-term use, although it can be used for several months under specialist supervision.

Antipsychotics

There is evidence that certain antipsychotic drugs have positive benefit in the treatment and management of anxiety. The method by which they relieve anxiety is not known, but these drugs are associated with emotional changes and effects on symptoms such as agitation. In anxiety management they are used in doses much lower than would be needed for their antipsychotic effects. Drugs such as haloperidol, flupentixol and tri-fluoperazine can be used as anxiolytics and have a quick onset. They are especially useful if the patient has a diagnosis of psychosis, as their anxiety may be related to this.

Like barbiturates and benzodiazepines, some of the side-effects of antipsychotic drugs can be compounded by alcohol.

Antidepressants

The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have a positive effect in generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder, although many of these drugs are not licensed for such indications. TCAs have been used in the past for mixed anxiety/depressive disorders but they do not appear to have a significant specific anxiolytic activity.

It may be that their anxiolytic effect is related to their sedative properties. It takes two to three weeks for the anxiolytic and antidepressant effect to develop, suggesting that the mechanisms for both are related.

Another type of antidepressant, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can appropriately be used in chronic anxiety of longer than four weeks’ duration. Their mechanism of action is fully explained in the section on depression. The anxiolytic action takes two to three weeks to develop which is concurrent with the onset of antidepressant effect, again suggesting that the mechanisms are related. Some SSRIs have associated increased anxiety until the antidepressant effect occurs, and for this reason concomitant use of a benzodiazepine for the first two or three weeks is often recommended in anxiety, with a low starting dose of SSRI building up as tolerated.

Treatment is usually long term and often doses are at the higher end of the dosage scale for full effect. Examples of SSRIs in common use for anxiety are:

- fluoxetine and sertraline, licensed to treat anxiety symptoms accompanying depression and for OCD;

- fluvoxamine, licensed for the treatment of OCD;

- citalopram, licensed for the treatment of panic disorder;

- paroxetine, licensed for the treatment of social phobia, panic disorder, OCD and mixed anxiety and depression.

Depression

Depression is one of the most common serious psychiatric illnesses. Depressive or affective disorders involve a disturbance of mood or affect (cognitive and emotional symptoms), which are frequently associated with changes in behaviour, energy levels, appetite and sleep patterns (biological and physiological symptoms). Depression sufferers report a poor quality of life or morbidity. This often extends to their carers and can be detrimental to their close relationships. Depression has a high incidence of mortality which can often be due to suicide.

Depression can be:

- Unipolar, where the mood or affect is always low. This is characterized by misery, malaise, despair, guilt, apathy, indecisiveness, low energy and fatigue, changes in sleep patterns, loss of appetite and thoughts of suicide. It can be either reactive or endogenous. Reactive depression implies that the cause of the illness is brought about by severe stress. Endogenous depression on the other hand occurs when no obvious external causative factor can be identified.

- Bipolar, where the mood or affect and behaviour swing between depression and mania. This type of depression has a greater tendency to include an inherited component.

For a diagnosis of depression the patient must have certain key symptoms and also exhibit some ancillary symptoms. This assists the diagnosis and categorization of the depression.

Key symptoms

- Depressed mood.

- Inability to experience pleasure from normally pleasurable life events such as sex (anhedonia).

- Lack of energy.

Ancillary symptoms

- Changes in weight and appetite.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Low self-esteem.

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation.

- Guilt or self-reproach.

- Difficulty in concentrating.

- Suicidal thoughts.

Depression can be defined as mild, moderate or severe based on the number and incidence of these symptoms.

The aetiology of depression is still unclear. The biological theories relating to the disease would suggest that there are many factors in the development of depressive disorder including psychological, genetic, biological and neurochemical.

Psychological factors

These are known to play a part in the development of many types of depression and can be categorized as follows:

- Childhood and developmental experiences that are seen as negative, such as abuse, be it physical, mental or sexual; separation from one or both parents with maternal separation being particularly traumatic; breakdown of the relationship between parents and/or problems with the parent/child relationship.

- An unusually high number of what are termed as ‘significant life events’. These are often ranked according to their perceived impact, with bereavement, especially of a spouse, topping the list. Surprisingly, ‘positive’ life events such as getting married or the birth of a baby also have a significant impact. This may be due to a major change in lifestyle.

- Stress which can be deemed as unusual or continual such as stress at work or in a relationship.

- The absence of a secure or confiding relationship. This can be particularly relevant to the elderly and those who have lost a loved one, and may also explain why those who live alone have a higher tendency to become clinically depressed.

These are implicated in many areas of mental and physical health. Although no individual genes have yet been identified in depressive disease, there is a strong suggestion from family and twin studies of a genetic basis for a vulnerability to depression. A number of genes may be related to the function of known neurotransmitters and receptors, suggesting a biological effect. Other genes may be involved in influencing how a person perceives and responds to a certain kind of event or stressor, which may lead to depression in certain people but not in others.

Biological factors

Biological factors have become a major focus for research into depression and antidepressant drugs. Two distinct areas are implicated:

- hormonal influences;

- the monoamine hypothesis.

Hormonal influences

Cortisol, a corticosteroid, is known as the ‘stress hormone’ and has been linked to depression. Many people go on to develop depression if they are subjected to repeated and prolonged stress. Ongoing research is linking corticosteroids with monoamines to try to complete the picture.

The monoamine hypothesis

Many monoamines have been implicated in depression. Monoamines are, as their name suggests, organic compounds with a single (mono) amine group. They have the biological function of being neurotransmitters and neuromodulators and exert their effects at receptors located predominantly on neurones. They were first implicated as having a role in depression in the 1960s. This was due to the fact that the main antidepressant drugs used at that time (the TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, MAOIs) both have chemical actions on monoamines. It was suggested that reduced levels of monoamines could be a causative factor in depressive illness, although this hypothesis can be argued both for and against. Hence the monoamine hypothesis could explain why:

- drugs that deplete levels of monoamines are depressant in their nature (e.g. reserpine, methyldopa);

- drugs that increase the availability of monoamines can improve mood in depressed patients (e.g. TCAs and MAOIs);

- the concentration of some monoamines is notably reduced in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of depressed patients.

But equally the hypothesis does not explain why:

- drugs that increase the availability of mono- amines have no effect on mood in depressed patients (e.g. amphetamines, cocaine).

- some older antidepressants have no effect on monoamine systems (e.g. iprindole);

- there is a therapeutic delay of two weeks for the full effects of monoamine antidepressants to be seen.

Medicine management of depression

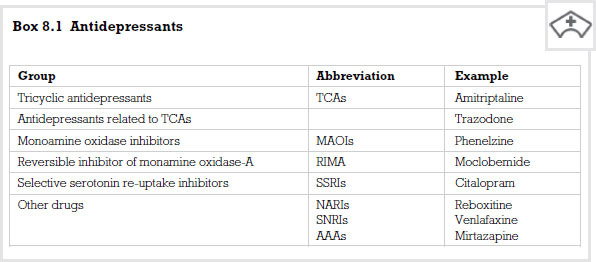

The BNF describes the main antidepressant drugs as shown in Box 8.1. We can now look at the mechanism of their action.

Tricyclic antidepressants

TCAs are powerful drugs which block the re-uptake of two major monoamines, noradrenaline and serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT). This means that there is more of the monoamine available to the receptors and this has an antidepressant effect. However, drugs in this class, such as amitriptyline, act at other receptors which can lead to side-effects such as:

- sedation, which can be useful if the drug is taken at night and insomnia is a problem. Sedation can be increased if the drugs are taken with alcohol and this can be problematic;

- cardiac rhythm problems, which can be severe in overdose;

- anticholinergic effects produced by action at muscarinic receptors, such as urinary retention and constipation;

- more seizures in epileptic patients.

- anticholinergic effects produced by action at muscarinic receptors, such as urinary retention and constipation;

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) exists in two forms, MAO-A and MAO-B, and both are responsible for chemically breaking down monoamines to render them inactive. MAOIs block this breakdown, and phenalzine is an example. The blocking leads to an increase in the availability of the monoamines which, as with TCAs, leads to an antidepressant effect.

These drugs are used infrequently due to their high risk of drug interactions, especially with other antidepressants. They are also able to interact negatively with some foodstuffs containing tyramine and dopamine (e.g. some cheeses, red wine, pickled herring and others). This interaction can cause blood pressure to increase to a dangerous level and patients on these medications are warned to avoid these foods.

MAOIs bind irreversibly but there is a reversible MAOI, moclobemide, which is also used.

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors

This group of drugs act selectively at serotonin (5-HT) neurones to produce their antidepressant action. They have very similar profiles regarding their antidepressant effects and the main differences between them lie in their abilities to cause drug interactions and effects.

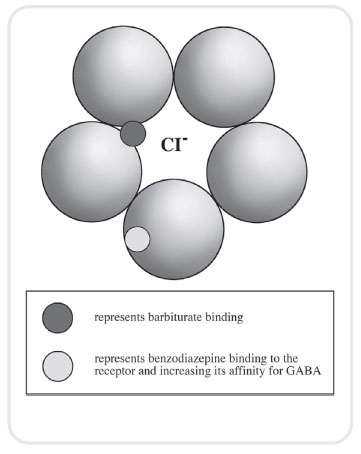

5-HT is released from the neurone into the synapse to have its action on receptors (see Figure 8.2). After release it is taken back up into the neurone that released it by a transporter located in the neuronal membrane. SSRIs inhibit the re-uptake of 5-HT from the synapse after it has been released. This leads to an increase in the amount of 5-HT present in the synapse available for action at receptors which respond to 5-HT and has an antidepressant effect (see Figure 8.3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>