Drugs Used in Infectious Disease

Overview

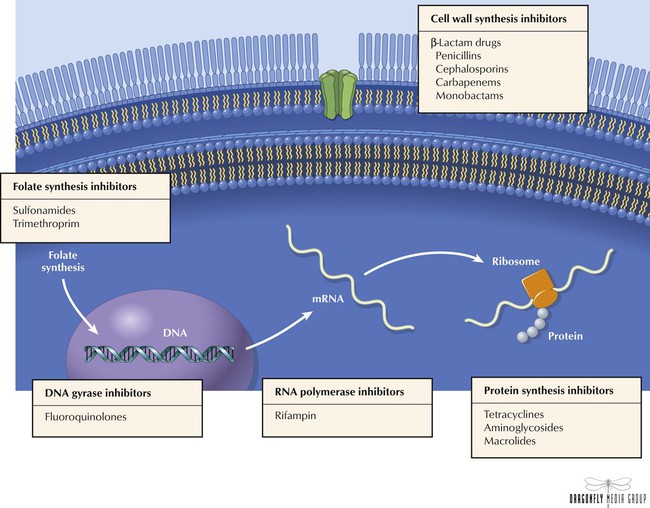

The clinical utility of antimicrobials is based on their ability to selectively kill or inhibit replication of invading organisms without causing significant harm to host cells. Designed to interfere with a phase of cell physiology that is unique to the pathogen, antimicrobials essentially make use of inherent structural differences among human, bacterial, viral, and fungal cells. Antibiotics are typically classified according to mechanism of action, chemical structure, and spectrum of activity against particular organisms. Drug classes include cell wall synthesis inhibitors (β-lactam drugs such as penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, monobactams); protein synthesis inhibitors (eg, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, macrolides); DNA gyrase inhibitors (fluoroquinolones); RNA polymerase inhibitor (rifampin); and folate synthesis inhibitors (eg, sulfonamides).

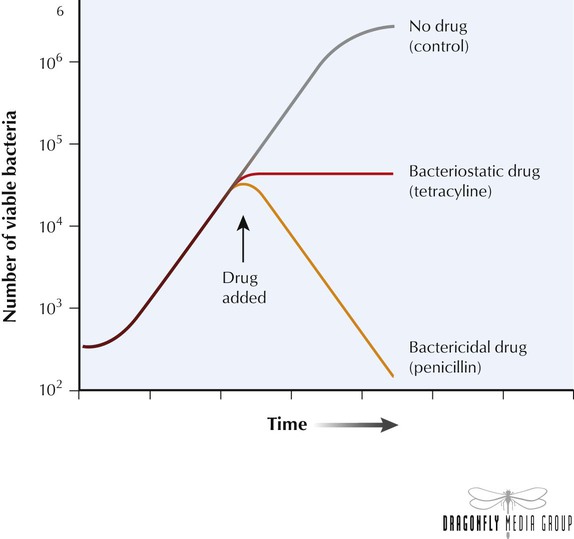

When characterizing the mechanism of action of an antibiotic, it is important to establish whether the agent is bacteriostatic or bactericidal. Bacteriostatic antibiotics arrest microbial growth and replication, which limits the spread of infection while the host’s immune system naturally eliminates the pathogens. If therapy ends before the immune system completely eliminates the organisms, a second cycle of infection may begin. Bactericidal agents kill bacteria, which leads directly to a reduced total number of viable pathogens in the host. Bactericidal agents are preferred for patients with neutropenia because these individuals have compromised immune systems and may not be able to eliminate remaining pathogens. Life-threatening infections such as endocarditis and meningitis should also be treated with bactericidal agents.

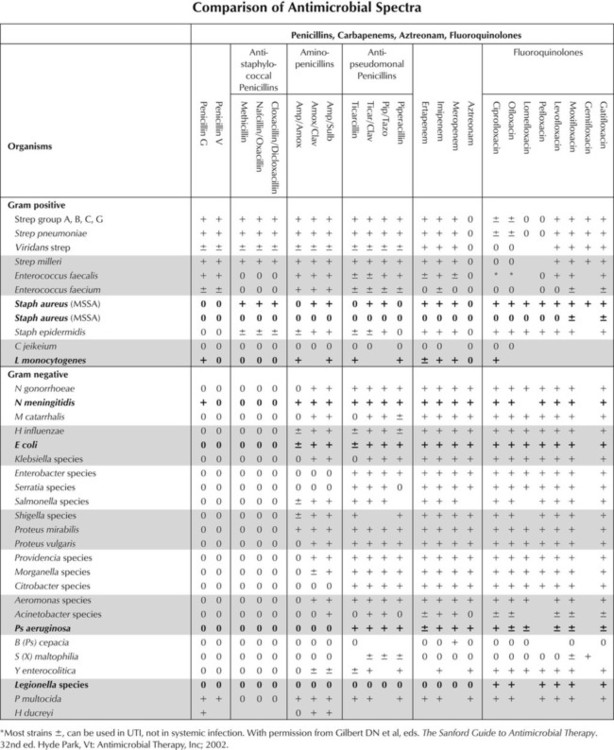

An antibiotic’s spectrum of activity refers to the range of pathogenic organisms affected by that drug. Antibiotics with a narrow spectrum of activity act on a single organism or a few groups of organisms; broad-spectrum agents such as fluoroquinolones are effective against a wide variety of microbes. Extended-spectrum antibiotics such as ampicillin-sulfbactam have an intermediate range of activity and target gram-positive organisms and some gram-negative species. Because broad- and extended-spectrum antibiotics eliminate a wide variety of microbial species, these agents can alter the nonpathogenic bacterial flora that normally colonizes the host and result in superinfection by organisms (eg, Candida, Clostridium difficile) whose growth would otherwise be suppressed.

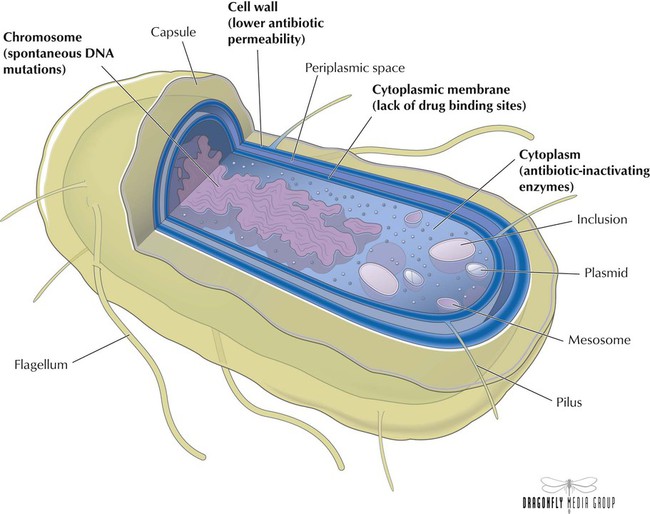

Bacteria such as Staphylococcus strains are resistant if their growth is not halted by the maximal level of an antibiotic that is tolerated by the host. Organisms develop into more virulent strains through mechanisms such as spontaneous DNA mutations. Main mechanisms of resistance are lower permeability of the antibiotic through the cell wall (eg, ampicillin), presence of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes (eg, β lactamases), and lack of drug-binding sites (eg, penicillin). Various factors contribute to the emergence of resistant strains, one of which is overprescribing of antibiotics in the community setting. Diagnostic uncertainty may be responsible: rapid diagnostic testing is available for only a few infections, so community physicians often distinguish between viral and bacterial infections on the basis of symptoms alone. For an uncertain diagnosis, physicians tend to use antibiotics. Other factors include inappropriate or indiscriminate drug use and patients’ not completing courses of treatment.

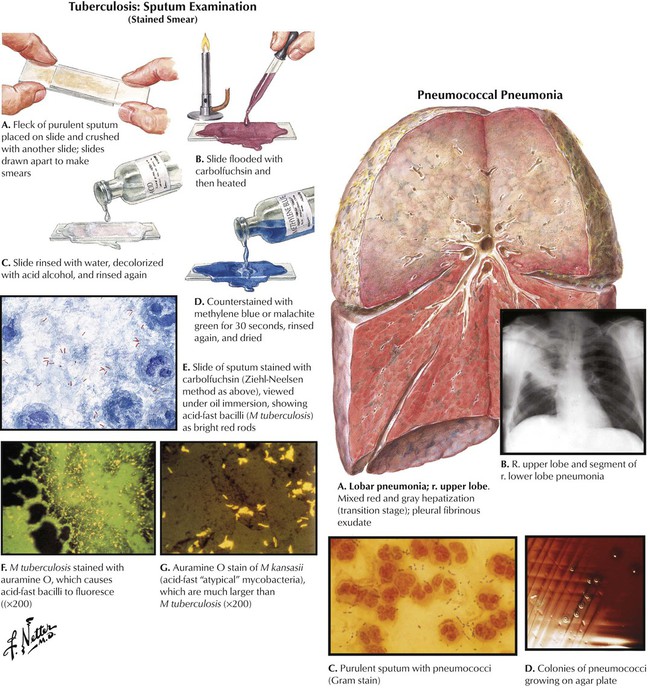

Increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics in the outpatient setting now seems to affect hospitals. Second- or third-generation cephalosporins, with or without a macrolide, are often given to patients who stay in the hospital for multidrug-resistant pneumococcal infections. However, overprescribing of these cephalosporins in communities has left hospitals with few options for patients who are already using these agents and present with such resistant infections. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains are increasingly found (now in 20% of all pneumococcal infections), with growing numbers of strains resistant to multiple drug classes, including macrolides and β-lactam antibiotics. Vancomycin is the fallback for therapy in such cases, but the utility of this drug may be limited because other bacteria such as Enterococcus and Staphylococcus aureus now have resistant strains. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains can now evade many drugs, so this disease has become difficult to treat.

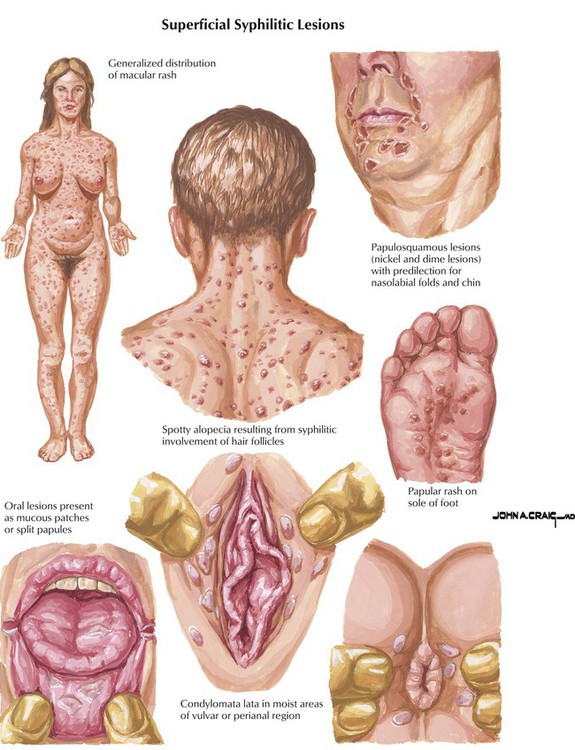

Originally obtained from fermentation of the mold Penicillium chrysogenum, penicillins are the oldest and still the most widely used of all antibiotics. These agents exert bactericidal activity by interfering with the last step of bacterial cell wall synthesis, which causes rapid cell lysis. Therefore, penicillins are ineffective against organisms that lack a cell wall, such as mycobacteria, protozoa, fungi, and viruses. Natural penicillins target gram-positive and gram-negative cocci, gram-positive bacilli, oral anaerobes, and spirochetes. These drugs have been the cornerstone of therapy for a diverse group of infections including pneumococcal pneumonia, syphilis, meningitis, tetanus, and gonorrhea. Penicillin G and penicillin V have similar spectra of activity, with the latter agent being more acid stable and thus better absorbed by the oral route, whereas penicillin G is administered via injection.

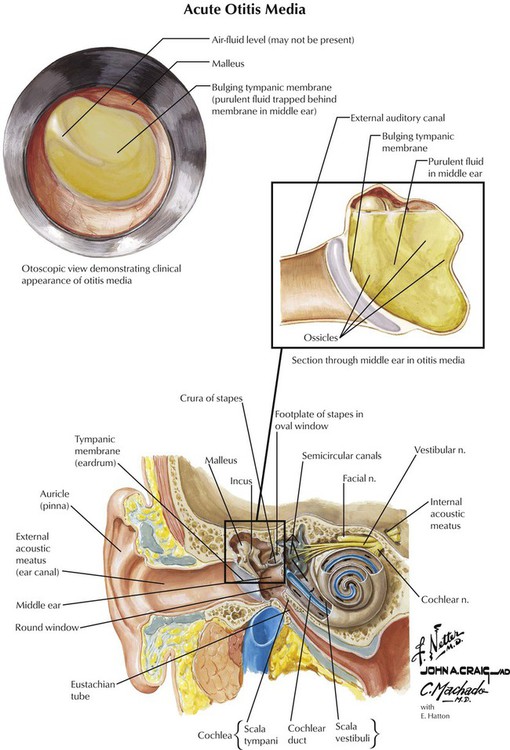

Aminopenicillins are similar to natural penicillins in spectrum of activity but are also active against many gram-negative organisms (eg, Helicobacter pylori) and against Listeria. These drugs are used for septicemia; gynecologic, skin, and soft tissue infections; and urinary, respiratory, and GI tract infections. Because these drugs have become inactivated by β lactamase–producing bacteria (eg, Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae), their use has declined. However, the CDC still indicates amoxicillin as the drug of choice for uncomplicated acute otitis media, despite the presence of drug-resistant S pneumoniae (DRSP) and H influenzae. The CDC urged use of a high-dose regimen to give amoxicillin a better chance to eliminate DRSP for very young patients with recent exposure to antimicrobials. If amoxicillin fails, antibiotics with activity against DRSP (eg, cefuroxime) or β lactamase–producing strains (ie, amoxicillin-clavulanate) should be tried.

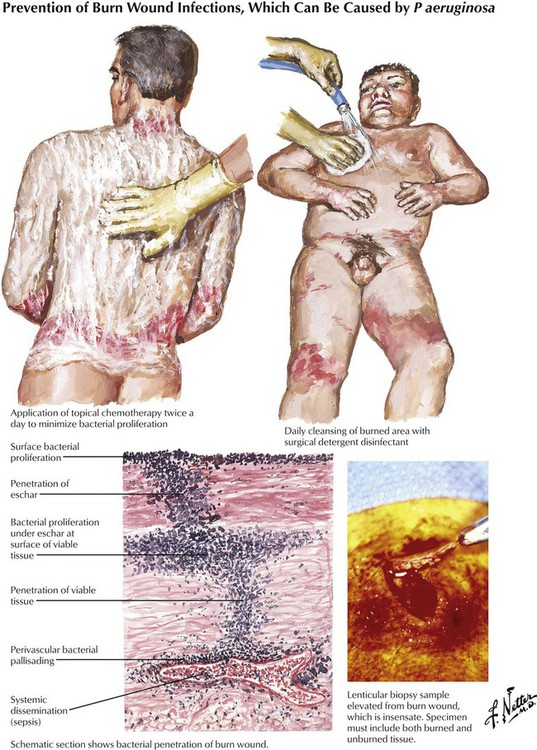

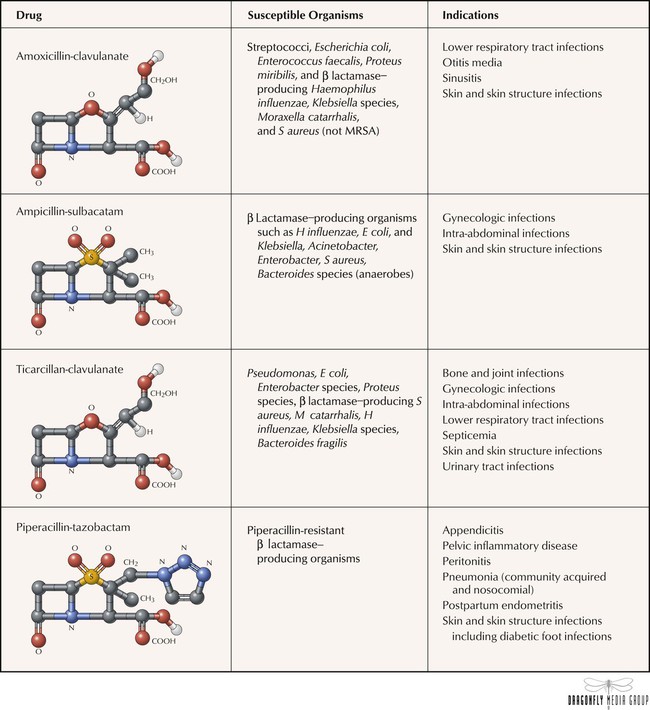

Antipseudomonal penicillins (carbenicillin, piperacillin, and ticarcillin) display improved activity against gram-negative organisms and are usually used in combination with aminoglycosides in patients with febrile neutropenia and in those with hard to treat nosocomial infections caused by strains of Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, Serratia, Bacteroides fragilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The antibacterial effects of all β-lactam antibiotics are synergistic with aminoglycosides because the former inhibit cell wall synthesis, which enhances diffusion of the latter into the bacterium. These drugs should never be placed into the same IV bag because positively charged aminoglycosides can form a precipitate with negatively charged penicillins. Like other penicillins, antipseudomonal agents can be inactivated by β lactamase and are therefore commonly used together with β-lactamase inhibitors (see Figure 10-9).

The structures of penicillins and other β-lactam antibiotics have in common a β-lactam ring that is essential to stability and antibacterial activity. After years of exposure to β-lactam antibiotics, a large number of bacterial organisms have developed resistance to the drugs by producing β lactamase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes the β-lactam ring and inactivates the antibiotics. β-Lactamase inhibitors—clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam—were developed to address this problem. With no antibacterial activity of their own, these inhibitors are used only in combination with β-lactam antibiotics, which creates a product that has extended activity against β lactamase–producing strains.

β Lactamase–resistant penicillins are semisynthetic penicillins that have the same coverage as natural penicillins but are designed to remain stable in the presence of β lactamase–producing staphylococcal organisms. Cloxacillin is used for treatment of septic arthritis; dicloxacillin is used for treatment of skin and soft tissue infections; oxacillin is used for treatment of sepsis, toxic shock syndrome, and infections of wounds and vascular catheters; and nafcillin is used for treatment of endocarditis, osteomyelitis, skin and soft tissue infections, and encephalitis. Unfortunately, many strains of S aureus have developed the ability to inactivate methicillin, leading to the increase of methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA). This pathogen is considered a serious source of nosocomial infections and produces diseases that are usually treated with vancomycin.

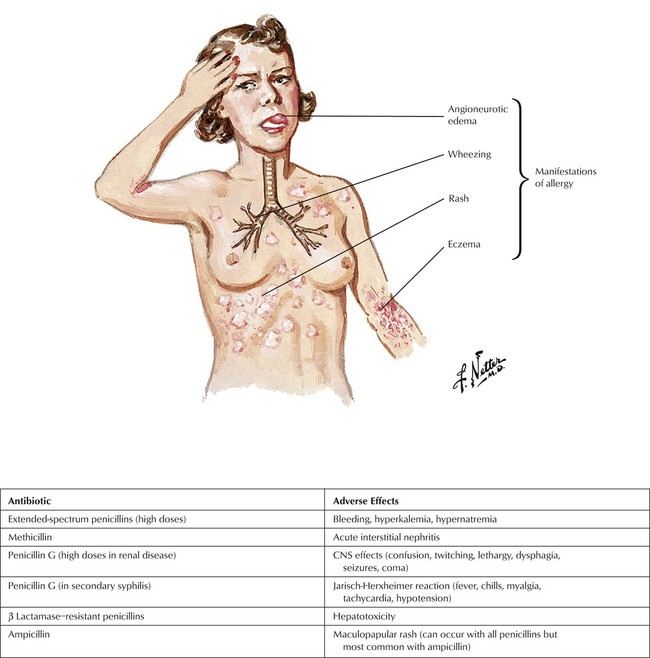

Although considered the safest of all antibiotics, penicillins can still cause significant adverse effects, with hypersensitivity reactions being most notable. Approximately 5% of patients experience some kind of reaction, which is actually an immune response to the penicillin metabolite penicilloic acid and can range from a maculopapular rash to angioedema and the more significant anaphylaxis. Cross-allergic reactions occur among all β-lactam antibiotics. Other reactions that pertain to specific agents are given in the table.

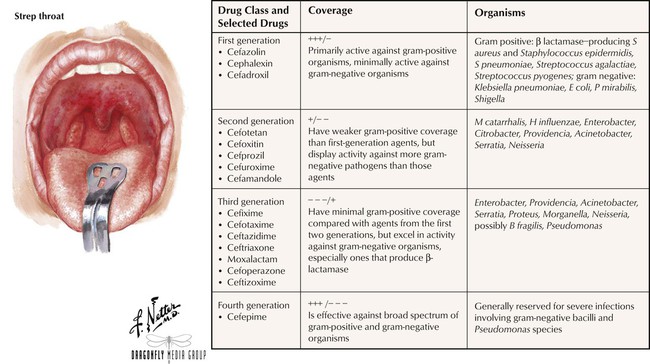

Chemically and pharmacologically similar to penicillins, cephalosporins inhibit cell wall synthesis and cause rapid cell lysis. These antibiotics are classified into first, second, third, and fourth generations on the basis of spectrum of activity and susceptibility to β lactamases. Agents in the first generation tend to have excellent gram-positive coverage but minimal gram-negative coverage, whereas agents in the higher generations tend to possess the reverse spectrum of activity. Also like penicillins, all cephalosporins can produce hypersensitivity reactions, ranging from a mild rash and fever to fatal anaphylaxis. Patients who are allergic to penicillins should avoid these agents because of cross-sensitivity of 5% to 15% between the 2 classes. Other adverse effects include GI disturbances and hematologic reactions including positive Coombs test results, thrombocytopenia, transient neutropenia, and reversible leukopenia.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree