Chapter 17 Drugs and the skin

This account is confined to therapy directed primarily at the skin and covers the following topics:

Dermal pharmacokinetics

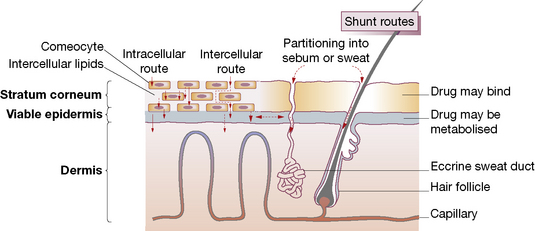

Human skin is a highly efficient self-repairing barrier that permits terrestrial life by regulating heat and water loss while preventing the ingress of noxious chemicals and microorganisms. A drug applied to the skin may diffuse from the stratum corneum into the epidermis and then into the dermis, to enter the capillary microcirculation and thus the systemic circulation (Fig. 17.1). The features of components of the skin in relation to drug therapy, whether for local or systemic effect, are worthy of examination.

• Physicochemical features: lipophilic drugs can utilise the intracellular route because they readily cross cell walls, whereas hydrophilic drugs principally take the intercellular route, diffusing in fluid-filled spaces between cells.

• Molecular size: most therapeutic agents suitable for topical delivery measure 100–500 Da.

Drugs are presented in vehicles (bases1), designed to vary in the extent to which they increase hydration of the stratum corneum; e.g. oil-in-water creams promote hydration (see below). Increasing the water content of the stratum corneum via occlusion or hydration generally increases the penetration of both lipophilic and hydrophilic materials. This may be due to an increased fluid content of the lipid bilayers. The stratum corneum and stratum granulosum layers become more similar with hydration and occlusion, thus lowering the partition coefficient of the molecule passing through the interface. Some vehicles also contain substances intended to enhance penetration by reducing the barrier properties of the stratum corneum, e.g. fatty acids, terpenes, surfactants. Encapsulation of drugs into vesicular liposomes may enhance drug delivery to specific compartments of the skin, e.g. hair follicles.

Transdermal delivery systems are now used to administer drugs via the skin for systemic effect; the advantages and disadvantages of this route are discussed on page 88.

Vehicles for presenting drugs to the skin

Solid preparations

Solid preparations such as dusting powders, e.g. zinc starch and talc,2 may cool by increasing the effective surface area of the skin and they reduce friction between skin surfaces by their lubricating action. Although usefully absorbent, they cause crusting if applied to exudative lesions. They may be used alone or as specialised vehicles for, e.g., fungicides.

Emollients and barrier preparations

Emollients

hydrate the skin, and soothe and smooth dry scaly conditions. They need to be applied frequently as their effects are short lived. There is a variety of preparations but aqueous cream, in addition to its use as a vehicle (above), is effective when used as a soap substitute. Various other ingredients may be added to emollients, e.g. menthol, camphor or phenol for its mild antipruritic effect, and zinc and titanium dioxide as astringents.3

Barrier preparations

Silicone sprays and occlusives, e.g. hydrocolloid dressings, may be effective in preventing and treating pressure sores. Masking creams (camouflaging preparations) for obscuring unpleasant blemishes from view are greatly valued by patients.4 They may consist of titanium oxide in an ointment base with colouring appropriate to the site and the patient.

Adrenocortical steroids

Actions

Adrenal steroids possess a range of actions, of which the following are relevant to topical use:

• Inflammation is suppressed, particularly when there is an allergic factor, and immune responses are reduced.

• Antimitotic activity suppresses proliferation of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and lymphocytes (useful in psoriasis, but also causes skin thinning).

• Vasoconstriction reduces ingress of inflammatory cells and humoral factors to the inflamed area; this action (blanching effect on human skin) has been used to measure the potency of individual topical corticosteroids (see below).

Uses

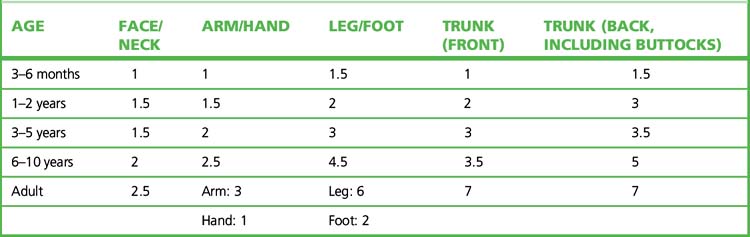

Topical corticosteroids should be applied sparingly. The ‘fingertip unit’5 is a useful guide in educating patients (Table 17.1). The difficulties and dangers of systemic adrenal steroid therapy are sufficient to restrict such use to serious conditions (such as pemphigus and generalised exfoliative dermatitis) not responsive to other forms of therapy.

Table 17.1 Fingertip unit dosimetry for topical corticosteroids (distance from the tip of the adult index finger to the first crease)

Guidelines for the use of topical corticosteroids

• Use for symptom relief and not prophylactically.

• Choose the appropriate therapeutic potency (Table 17.2), e.g. mild for the face. In cases likely to be resistant, use a very potent preparation, e.g. for 3 weeks, to gain control, after which change to a less potent preparation.

• Choose the appropriate vehicle, e.g. a water-based cream for weeping eczema, an ointment for dry, scaly conditions.

• Prescribe in small but adequate amounts so that serious overuse is unlikely to occur without the doctor knowing, e.g. weekly quantity by group (see Table 17.2): very potent 15 g; potent 30 g; other 50 g.

• Occlusive dressing should be used only briefly. Note that babies’ plastic pants are an occlusive dressing as well as being a social amenity.

• If it’s wet, dry it; if it’s dry, wet it. The traditional advice contains enough truth to be worth repeating.

• One or two applications a day are all that is usually necessary.

Table 17.2 Topical corticosteroid formulations conventionally ranked according to therapeutic potency

| Potency | Formulations |

|---|---|

| Very potent | Clobetasol (0.05%); also formulations of diflucortolone (0.3%), halcinonide |

| Potent | Beclometasone (0.025%); also formulations of betamethasone, budesonide, desoximetasone, diflucortolone (0.1%), fluclorolone, fluocinolone (0.025%), fluocinonide, fluticasone, hydrocortisone butyrate, mometasone (once daily), triamcinolone |

| Moderately potent | Clobetasone (0.05%); also formulations of alclometasone, clobetasone, desoximetasone, fluocinolone (0.00625%), fluocortolone, fluandrenolone |

| Mildly potent | Hydrocortisone (0.1–1.0%); also formulations of alclomethasone, fluocinolone (0.0025%), methylprednisolone |

Important note: the ranking is based on agent and its concentration; the same drug appears in more than one rank.

Choice

Topical corticosteroids are classified according to both drug and potency, i.e. therapeutic efficacy in relation to weight (see Table 17.2). Their potency is determined by the amount of vasoconstriction a topical corticosteroid produces (McKenzie skin-blanching test6) and the degree to which it inhibits inflammation. Choice of preparation relates both to the disease and the site of intended use. High-potency preparations are commonly needed for lichen planus and discoid lupus erythematosus; weaker preparations (hydrocortisone 0.5–2.5%) are usually adequate for eczema, for use on the face and in childhood.

Adverse effects

Used with restraint, topical corticosteroids are effective and safe. Adverse effects are more likely with formulations ranked therapeutically as very potent or potent in Table 17.2.

Other effects include:

Other complications of occlusive dressings include infections (bacterial, candidal) and even heat stroke when large areas are occluded. Antifungal cream containing hydrocortisone and used for vaginal candidiasis may contaminate the urine and misleadingly suggest Cushing’s syndrome.7

Applications to the eyelids may get into the eye and cause glaucoma.