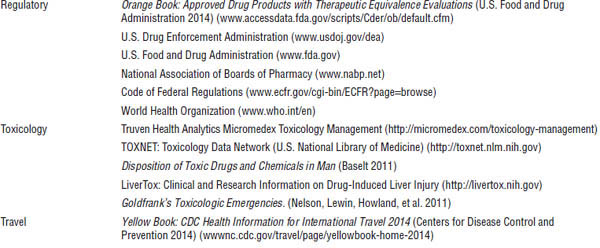

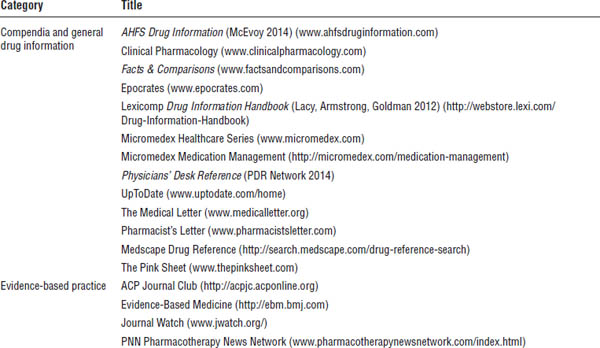

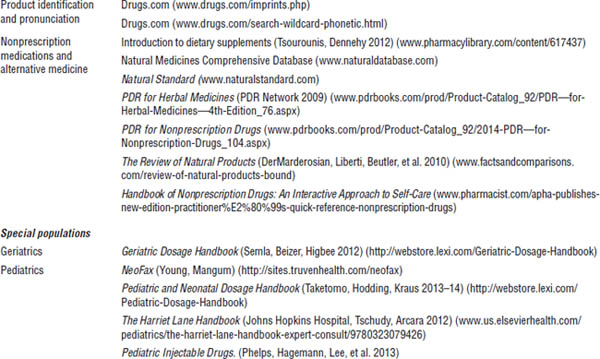

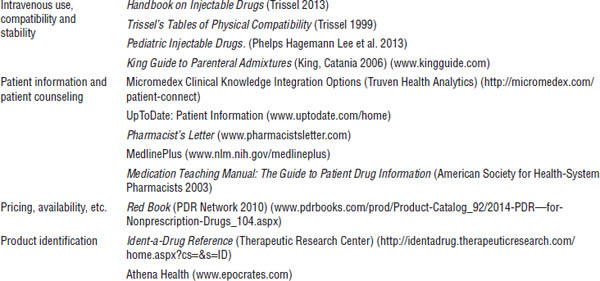

Table 10-1. Examples of Drug Information Resources by Category (Secondary and Tertiary Literature)

Disadvantages of tertiary resources include publication lag time and the potential for incomplete information as a result of space limitations or inadequate searching techniques. Because of the inherent limitations of tertiary references, a search of the secondary literature is typically appropriate to ensure identification of up-to-date primary literature.

Secondary and primary resources

Secondary references index journal article citations and abstracts, allowing retrieval of primary literature. With more than 20,000 biomedical journals published annually, appropriate search techniques are crucial to identify relevant primary literature. Electronic access to secondary databases allows the search of millions of citations through a single search with the use of keywords and linked keywords (see Table 10-2).

To be thorough and comprehensive, one should use several databases when researching a drug information question. Once relevant primary literature is identified through the secondary databases, it must be evaluated to ensure quality and relevance.

Several examples of secondary drug information services are available online, including the following:

■ Clinical Trials Information: www.clinicaltrials.gov

■ Clinical Guidelines: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines

■ National Quality Measures Clearinghouse: www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov

■ Systemic Reviews: www.systematicreviewsjournal.com

■ Evidence-Based Practice reviews: www.acponline.org/clinical_information/guidelines/guidelines

There are even Web sites to obtain medical care online (see DeJong, Santa, Dubley 2014). A Google or a Google Scholar search will identify most of those information sources.

Table 10-1 lists other examples of secondary resource databases. Secondary databases may be available for access directly or through a provider, such as Embase (www.elsevier.com/online-tools/embase) and Ovid (www.ovid.com). MEDLINE may be accessed free through PubMed (www.pubmed.gov). Primary literature consists of clinical studies and reports. Evaluation of the primary literature is discussed in Chapter 11, “Clinical Trial Design.”

Table 10-2. Examples of Secondary Literature Databases

Database | Source |

Cumulative Index to | |

Embase | |

Iowa Drug Information | |

The Cochrane Database | |

MEDLINE | |

Ovid |

10-4. Application of Drug Information Skills for Delivery of Patient Care

Pharmacists must be able not only to retrieve drug information, but also to communicate the information effectively. Effective written and oral communication skills are a fundamental component of pharmacy practice. With more complex treatment regimens, pharmacists today require more advanced problem-solving skills than previously. They must formulate answers to increasingly complex questions that necessitate a solid foundation of drug information skills. Pharmacists must remain current with pharmacy and medical literature to provide the most up-to-date drug information available. Pharmacists are expected to be the experts on medications and to use their knowledge of medications to improve drug therapy outcomes and patient care.

Drug information provided during the patient counseling session is a type of verbal drug information. When patients contact the pharmacy with questions regarding medications, pharmacists have the opportunity to communicate drug information verbally or electronically. Any verbal, printed or electronic communication of drug information to the patient must be well thought out, thorough, and complete, containing the pertinent components of medication information and tailored to the individual patient’s specific needs. During the counseling session, information regarding dosage, administration, storage, drug interactions, and side effects may need to be communicated, depending on the individual patient and situation. Each pharmacist must develop proficiency in the art of providing patient-specific drug information.

Effective patient care requires that pharmacists intervene when appropriate to advocate for the patient’s well-being. Pharmacists who effectively communicate evidence-based knowledge to physicians and other prescribers can positively influence a patient’s quality of life and care.

Pharmacists also provide written drug information. Responding to e-mail, patient medication guides, pamphlets, and handouts containing information about medications are all types of written drug information. Pharmacists may contribute to the production of newsletters and other types of publications for both patients and health care providers. Pharmacists may be involved in developing important documents that guide medical practice, such as therapeutic guidelines and formulary development.

Additionally, drug information skills include the ability to identify the true question being asked, followed by a systematic approach to searching for the answer or solutions and formulation of a thorough and appropriate response.

Systematic Approach to Answering a Drug Information Request

The successful application of drug information skills requires use of a systematic approach for searching drug information resources. The first step on receipt of a drug information question or request is to obtain pertinent background and demographic information from the requester. Next, the pharmacist must confirm the ultimate question to formulate an appropriate search strategy. The question should be categorized by the type of information requested, such as “drug interactions,” “adverse effects,” “pharmaco-economics,” or “pediatrics.” Categorizing the question is useful for deciding which drug information resources will be most appropriate to use during the search. Once the question is categorized, the pharmacist should plan how to search the literature. Finally, evaluation of the retrieved literature forms the basis for the formulation of an appropriate response to the requester.

Following the categorization of the question, a systematic approach includes a search of the tertiary and secondary literature and identifies primary literature that is relevant to the question or request. Formulating a response that has been thoroughly searched and documented and appropriately answers the initial question is a skill that is essential to the provision of drug information. One must also keep the legalities and liabilities of providing drug information in mind when formulating a response to a drug information request. For example, a pharmacist may have used a source that contained an error in dosing that was later corrected, but the pharmacist may not have seen the correction. If the patient was harmed by the information provided, the greatest liability would be on the source, but the pharmacist may share some liability. This is a reason to use multiple sources in responding to a drug information question.

Clinical decision support systems

Clinical decision support systems (CDSSs) are used to support decision making in a variety of clinical domains. These systems are computer-based programs designed to provide information support for health professionals making clinical decisions typically at the point of care and integrated in pharmacy computer systems. A CDSS system has three basic components: (1) an inference engine or artificial intelligence, (2) a knowledge base, and (3) a communication mechanism. These systems have emerged as an important part of any clinical information system, particularly in the era of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems that allow direct entry of orders and instructions for the treatment of patients by a clinician. The orders are communicated through a computer network to the hospital staff or other various departments responsible for fulfilling an order, including pharmacy, radiology, or laboratory. Used properly, CPOE decreases delays in order completion, reduces errors related to handwriting or transcriptions, allows order entry at the point of care or off site, provides error checking for duplicate or incorrect doses or tests, and simplifies inventory and posting of charges.

Literature Searching Skills and Sources

Some basic skills for searching the literature are necessary for identifying the most up-to-date, evidence-based information as well as for formulating the most comprehensive response possible. Millions of articles may be accessed through the Internet. To retrieve articles in a comprehensive and timely manner, pharmacists must be proficient at searching the secondary literature databases, keeping in mind the importance of searching different databases to ensure a comprehensive search.

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) is the world’s largest medical library and provides several bibliographic, factual, and evidence-based drug and dietary supplement information resources. PubMed is maintained by the NLM and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to provide access to millions of citations from the biomedical literature. PubMed is a database of biomedical journal citations and abstracts for thousands of journals published in the United States and worldwide. Access to the NLM’s MEDLINE service is available worldwide through the Internet at no cost. MEDLINE is a large electronic bibliographic database, containing citations from the late 1940s to the present, accessible through PubMed.

The “LinkOut” feature of PubMed allows direct access to full articles from the journal’s Web site and related Internet resources. Depending on the individual citation, a fee may be charged for access to the full text. Most medical centers and academic institutions have subscriptions to many journals, thereby allowing direct access to selected journals.

Pharmacists conducting literature searches must be able to retrieve appropriate articles that are relevant to the inquiry. Using efficient search techniques is important to avoid retrieving an overwhelmingly excessive number of irrelevant citations.

MEDLINE citations are indexed through the controlled vocabulary developed by the NLM, known as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). When conducting a search of the MEDLINE database through PubMed, the pharmacist should first use MeSH terms to ensure that all relevant information is identified through the search. Keywords may be used to conduct a search in PubMed when a search using MeSH terms does not produce relevant results or when a MeSH term is not available for the desired search term.

Boolean operators (and, or, and not) are often used to combine relevant search terms, helping to narrow and focus the search. The term and may be used to combine two or more search terms, allowing retrieval of citations containing only both concepts. The Boolean operator or will allow access to citations including either term and will, therefore, potentially produce a larger number of results in a literature search than and. The term not is used to limit a search and, therefore, will likely produce fewer results; however, a disadvantage of using this term is that relevant articles may be excluded.

Literature searches can be made more effective by combining appropriate MeSH terms and by imposing appropriate limits on the search, such as by type of publication or range of publication date. Because no single search strategy will always produce satisfactory results, conducting several searches with various combinations of search terms is important to achieve the most comprehensive search possible.

Patients and health care professionals commonly ask questions of pharmacists about current health news topics. In this case, the Internet may be an appropriate source to begin a search for the requested information; however, drug information provided by news sources should be cautiously interpreted and should always be verified by reputable sources of drug information.

Information pertaining to the U.S. government or FDA can be identified through the FDA Web site and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web site (www.cdc.gov). These Web sites also include clinical information and information about new drug approvals and FDA-required information in the labeling. For example, when a product package insert is needed, the company Web site or the FDA Web site is an appropriate starting place.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Web site (www.ashp.org) provides useful information regarding drug shortages and materials for formulary development.

Several sources provide general reviews and reports that are searchable and provide an excellent resource for many questions pharmacists receive from patients and practitioners. For example, Pharmacist’s Letter (http://pharmacistsletter.com) and Prescriber’s Letter (http://prescribersletter.com) offer print and online access to practical information, including patient information materials for subscribers. The publishers of Pharmacist’s Letter and Prescriber’s Letter also produce the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database (www.naturaldatabase.com), which provides information on supplements and is of great interest to both patients and health care professionals.

Another source is Internet Drug News.com for Pharmaceutical News & Information: Pharmaceutical News Harvest (www.coreynahman.com), a free service updated daily that focuses on recent news and pharmaceutical manufacturers activities.

For investigational drugs and pharmaceutical manufacturer’s information, First Word Pharma (www.firstwordpharma.com/#axzz2tPDNXpnN) is a free source of information.

Medscape Drug Reference (http://firstwordpharma.com) is a general drug information database that may be freely accessed through the Internet. The drug information contained in this reference is considered to be broad in scope and depth and relies on authoritative sources of drug information.

Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.org) is a free online resource that is edited by its users. Although consumers may use this source for drug information, potential problems include errors in information, lack of referenced documentation, and omissions of information. Wikipedia may be a useful source for providing information supplementary to other more reliable sources, but pharmacists should be cautious of user-edited sites as a definitive source of drug information.

Many journals and textbooks are now available electronically through the Web, allowing greater ease of use and increased availability. They are usually available online sooner than they are available in print. Many of these sources also have apps for smartphones and tablets.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree