Drug Allergy, Abuse, and Poisoning or Overdose

Overview

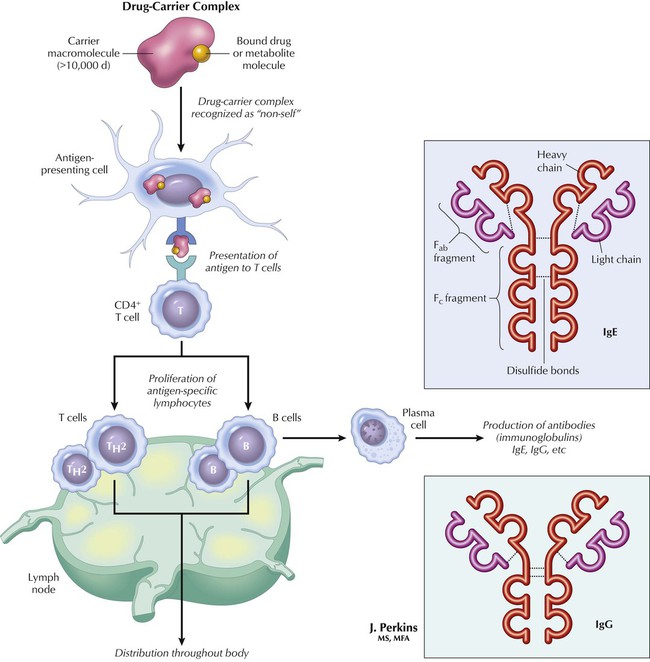

Only a few drugs have a molecular size (>10,000 d) sufficient to induce an allergic reaction by themselves. Induction of an immune response more often occurs when a small drug molecule, metabolite, or excipient (inert substance in a prescription) covalently binds to some large endogenous macromolecule (carrier), such as a protein, and becomes allergenic. The immune system becomes sensitized during the initial exposure, although the allergic response is not elicited at this time. Antigen-specific antibodies of the T- and B-cell type proliferate in lymphatic tissue, and some remain there (as memory cells) and are clinically silent until reexposure to the antigen (drug-carrier complex). The response to reexposure can be quick and severe, even to a small dose of the drug. Four types of drug allergy are generally distinguished: anaphylactic, cytotoxic, immune complex vasculitis, and cell mediated. Management generally involves treating the symptoms and supporting vital functions.

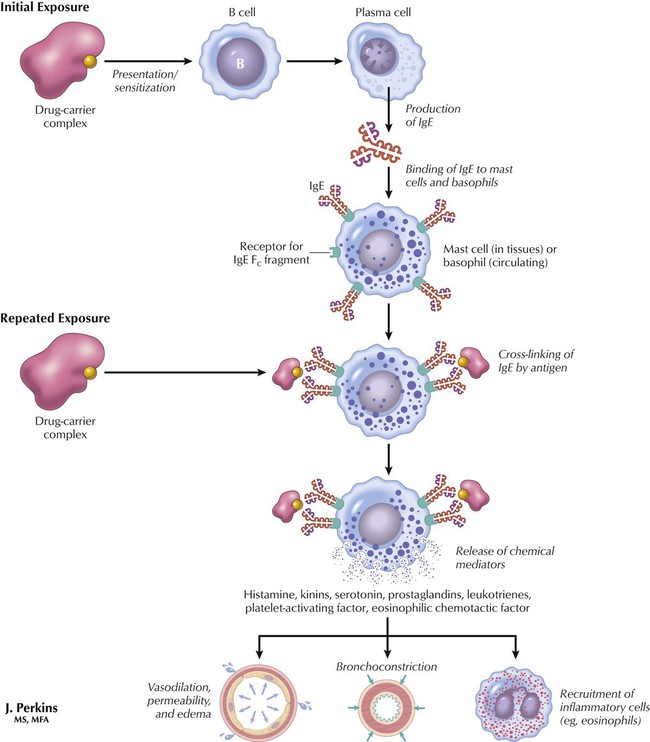

After initial exposure to drug antigen (drug-carrier complex), macrophages and interleukins convert B cells into IgE/receptor-expressing cells that circulate in blood (as basophil granulocytes) or reside in tissues (as mast cells). Reexposure to drug antigen results in binding to paired IgE receptors and release of various chemical mediators such as histamine, kinins, serotonin, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, platelet-activating factor, and eosinophilic chemotactic factor. Histamine and other bioactive substances released into the bloodstream cause blood vessels to dilate and tissues to swell. The effect may be life-threatening if airway obstruction, blood pressure decrease, or heart arrhythmias occur. Type I reactions can have a rapid onset (minutes) and are similar to those seen in hypersensitivity reactions to insect stings, extrinsic asthma, and seasonal rhinitis.

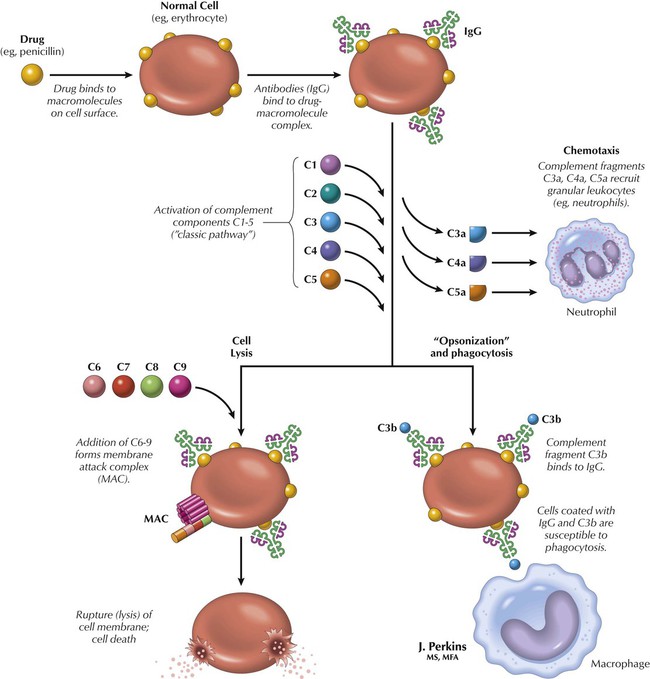

If antigen (drug)-antibody (IgG) complexes adhere to a cell surface, the immune response can damage or kill the cell. This effect occurs because the binding of the complex activates complement, which is a family of proteins that circulate in the blood in an inactive form until activated by an appropriate stimulus. Activated complement is normally directed against microorganisms, but when directed against a cell, complement causes lysis and death of the cell, promotes phagocytosis, attracts neutrophil granulocytes (chemotaxis), and stimulates other inflammatory responses. An example is allergy to penicillin. Penicillin binds to red blood cells, antibodies bind to the penicillin, complement is activated, and the cell is damaged or dies, which leads to drug-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia, agranulocytosis, and thrombocytopenia.

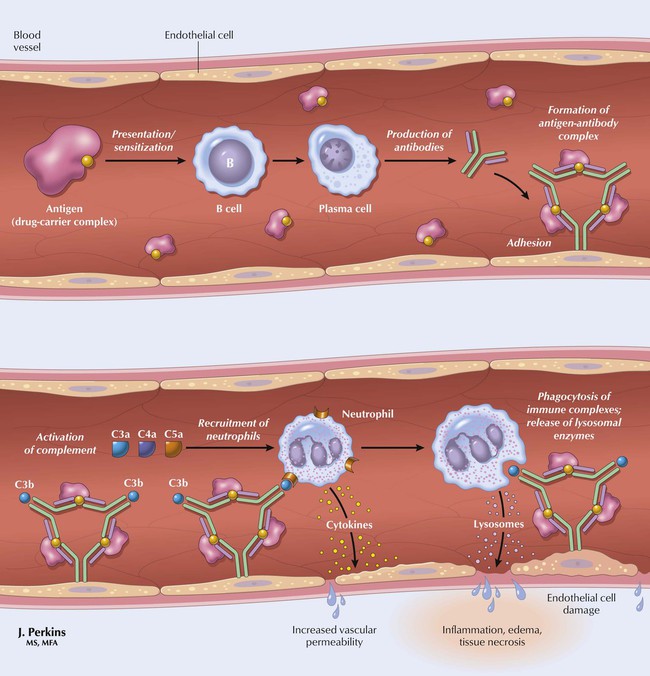

If drug antigen-antibody complexes adhere to cells of vascular tissue, the immune response can attack not only the antigen-antibody complex but also the healthy cells of the vessel to which the complex is attached. This result can cause damage or death of the vessel’s cells. Activated complement, inflammation, and vasculitis damage vessel walls and result in the symptoms of serum sickness, which include malaise, fever, rash, arthralgia (pain in a joint), lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, and characteristic rash and eruptions along the sides of the feet and hands.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree