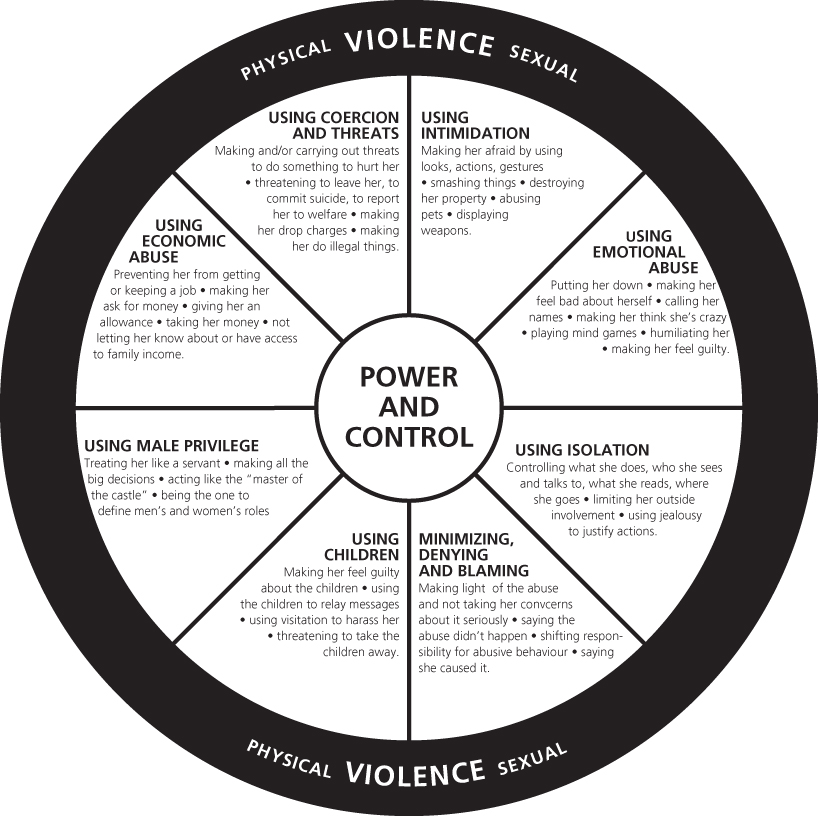

Chapter 3 Although mens are also abused, generally there is a strong relationship between DVA and female gender. For the purposes of this chapter, the domestic violence perpetrator is referred to as ‘he’ and the DVA survivor as ‘she’, in order to distinguish between them and to reflect the more typical abuser/abused. The epidemiology of gender-based violence is covered in Chapter 1. The Home Office recently amended the definition of domestic violence in light of recent discoveries of internal sex-trafficking rings in the UK and growing awareness of teenagers taking on adult roles both in partnerships and in having babies early. The new definition (Box 3.1) includes anyone aged 16 years or older, which may help to ensure that teenagers are not denied access to services for DVA survivors. While teenage survivors of DVA also come under child-protection legislation, they might not find help if they are independent of their parents. ‘Any incident of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse (psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional) between adults who are or have been intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality. This includes issues of concern to black and minority ethnic communities such as so called “honour” based violence, female genital mutilation and forced marriage, and it is clear that victims are not confined to one gender or ethnic group.’ The power–control dynamic emerged as the key driver for perpetrators in qualitative research with DVA survivors carried out by the Duluth Programme in Minnesota, USA in the 1980s. The violence and nonviolence wheels (see Figure 3.1) derived from this research have since formed the basis of training on Recognising, Responding and Referring those experiencing DVA in both the UK and the USA. Police witness statements from survivors and ongoing testimonies of abuse survivors have confirmed the validity of the model in practice. Figure 3.1 The Duluth model training wheel. ‘The Power and Control Wheel was developed in Duluth by battered women who were attending education groups sponsored by the local women’s shelter. The wheel is used in our Creating a Process of Change for Men Who Batter curriculum, and in groups of women who are battered, to name and inspire dialogue about tactics of abuse. While we recognize that there are women who use violence against men, and that there are men and women in same-sex relationships who use violence, this wheel is meant specifically to illustrate men’s abusive behaviors toward women. The Equality Wheel was developed for use with the same groups.’ http://www.theduluthmodel.org/training/wheels.html (last accessed 12 February 2014). The violence wheel’s subcategories of behaviours, as described in the segments, might be updated to include harassment, humiliation and threat via social networks, text messages and the Internet, as well as same-sex relationships and woman-on-man DVA. The underlying dynamic of power and control remains, even if the form it takes might vary across genders and cultures. Those most at risk of experiencing DVA are those with vulnerabilities. In short, bullies prefer the vulnerable because they are easier to control and isolate, giving them the sense of power they desire. Vulnerable groups in society are: women relative to men; the elderly; pregnant women; children; teenagers; the disabled; communities that are already discriminated against by others. The last include first-generation immigrants who do not speak English and those in same-sex relationships or transgender people. Already stigmatised, their isolation is greater, so revealing abusive experiences is more difficult and more dangerous (see Chapters 7 and 9). Further discussion of ‘cultural issues’ is found in Chapter 2. The vast majority of DVA research remains focused on men as perpetrators and women and children as ‘victims’ or ‘survivors’. The term ‘survivors’ is preferred to ‘victims’ because it indicates the active tenacity that those assailed must possess in order to survive daily and focuses on their strengths and assets. There is some justification for highlighting women as survivors, given that men are usually more physically powerful and the murder of women by men is much more common than vice versa. UK police audits have found that about 50% of murdered women are killed by a partner or former partner. Murder of men is more common overall, but it is much less often by their domestic partners. Women experience more sexual violence, more severe physical violence and more coercive control from their partners and are more likely to be afraid of their partners. Sexual abuse is committed by men much more commonly than by women. A woman’s physical vulnerability increases when she is pregnant (see Chapter 16). Indeed, one-third of women experiencing DVA are hit for the first time following impregnation. Those who become pregnant as teenagers are more likely than older women to be in an abusive relationship and also to have escaped DVA in their parental home. In so-called ‘honour-based violence’, the assertion of the power and control that resides in a strict, authoritarian, patriarchal culture becomes the family’s role, rather than an individual’s. This is carried out by members of the immediate or extended family, which may include women as well as men. A daughter may incur so-called ‘shame’ and ‘dishonour’ by behaving in ways that might seem usual to another culture’s eyes. Sometimes just a rumour is enough to elicit an abusive reaction (e.g. coming home late, wearing ‘inappropriate’ make-up or clothing, having relationships outside the approved group, running away or refusing an arranged or forced marriage – see Box 3.2). Women who are immigrants and are isolated by language may be unaware of available support. UK law protects the individual, but she must first escape her community to access the protection the law affords. Absolute confidentiality is paramount if this is to be achieved safely.

Domestic Violence and Abuse

OVERVIEW

Gender

Teenagers

Box 3.1 Home Office definition of domestic violence, 2012

Power and control: an explanatory psychosocial model

Who is at risk?

Women

Pregnant women

Women at risk of so-called ‘honour’-based violence and forced marriage

Box 3.2 Forced marriage

Identifying factors to look out for during consultations include patients who:

Good medical practice includes:

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine