![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Establish documentation practices that can be easily integrated into a community pharmacy’s workflow.

2. Utilize the assistance of ancillary staff, student pharmacists, residents, and staff pharmacists in documenting clinical services within the community pharmacy setting.

3. Develop a method for documenting pharmacist interventions and patient outcomes within the community pharmacy setting that abide by state and federal law.

4. Report these outcomes to other members of the pharmacy team, other health-care providers, and third-party payers in support of the value of clinical pharmacist services within the community pharmacy setting.

5. Apply these outcomes to improve clinical practice within the community pharmacy setting.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

“If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen,” is a statement that resonates with many pharmacists and other healthcare professionals. Whether it was during a pharmacy law class or during clinical rotations, the first time a pharmacist hears this quote marks the beginning of a dedication to documentation. From product verification to narcotic inventories, documentation is required for most activities performed by a pharmacist. For years, the act of documentation by pharmacists served as a means to assign ownership. Documenting that a bottle of Oxycontin® (oxycodone ER) was double counted or placing initials on a work log assigned liability and protects both the pharmacist and the patient in the event of unexpected adverse effects or achievement of optimal therapeutic response.

The livelihood of a pharmacist continues to rely largely on documentation practices as the profession expands clinical services in outpatient practice settings, namely community pharmacies. As pharmacists’ authorities expand beyond providing vaccinations and therapeutic drug-level monitoring, documentation practices have become more intricate, most cases requiring more that just initials to not only establish ownership but payment for services as well.

Proper documentation is required by state and federal law for pharmacists to be reimbursed for the provision of clinical services, such as immunizations and medication therapy management (MTM) services. Documentation is mandatory to operate any patient care practice.

Cipolle, Strand, and Morley have defined documentation in the following manner: “Documentation refers to all patient-specific information, the clinical decisions, and the patient outcomes that are recorded for use in practice. This includes everything written down in long-hand, or entered into a computer program that becomes data and is used to facilitate the care of patients.”1 Pharmacy as a profession has come a great distance in terms of documentation of patient care services, but the profession lacks a uniform method of documentation and billing of clinical services.2 Key stakeholders within the health-care system have recognized that as a limiting factor, and while this chapter will not solve the problem of a universal electronic health record (EHR), it will highlight the importance of documentation and describe key components that will be required for the documentation of patient care services.

WHY DOCUMENT?

WHY DOCUMENT?

Documentation is necessary for a spectrum of patient care services provided in a pharmacy, and the level and breadth of documentation will vary depending on the patient care service(s) provided. While not universally required by law, any intervention that a pharmacist makes during the process of dispensing should be documented accordingly for several reasons. Details of that intervention such as a statement of the problem, process to resolve, and a dated resolution will not only enhance the continuity of care and allow for compensation of services when contracted but also provide some level of protection for the pharmacist in the event of legal ramifications. For example, if a drug–drug interaction is identified during the dispensing process, the resolution of that problem (i.e., educating the patient) should be documented electronically in the dispensing system. Any communication with other health-care providers regarding a patient’s care should be appropriately documented, such as accepted or rejected pharmacist recommendations for changes in the patient’s medication regimen.

Continuity of Care

Proper documentation requires the pharmacist to capture information about a patient encounter. Whether the patient was being seen for an immunization or a comprehensive MTM session, the information shared through documentation establishes a record of that service. A pharmacist must be aware of the information essential to the continuity of that patient’s care and include information necessary for the next health-care provider to further assist the patient in their health-care management.

Professional Liability

Documentation serves as official record of service provision and allows for maintenance of patient records according to legal standards. To this point, documented information must be accurate and consistent with practice and institution policies and standards. For example, if during a session, the pharmacist provides the patient with names of over-the-counter medications that can be used for a rash, the names of those agents must be documented. If those agents are listed and the pharmacist did not note that the patient was instructed on how to use and administer those agents, the pharmacist may be considered at risk for liability should the patient experience an adverse event.

Some state boards of pharmacy have established regulations to manage clinical services provided within community pharmacy settings. These regulations currently address documentation requirements for pharmacists providing vaccinations. However, as MTM services continue to establish a niche within the community setting, more states will look to require additional documentation standards.

Regulatory Policy

In addition to what is currently expected for clinical practice, documentation has legal implications as well. Thorough and consistent documentation practices protect the word and work of the pharmacist from liability when the presence or quality of services rendered is in question. Additionally, some third-party payers may require very specific pieces of information, and pharmacists must adhere to these requirements to prevent infarctions upon an audit.

For example, in New York State, where a pilot program for MTM is being implemented, program guidelines state that each Medicaid MTM-designated pharmacy must retain a hard copy of the MTM Consultation Form, signed enrollee Consent for Release of Medicaid Information to Health-Care Providers form, and other documentation pertinent to the visit for a minimum of 6 years.3

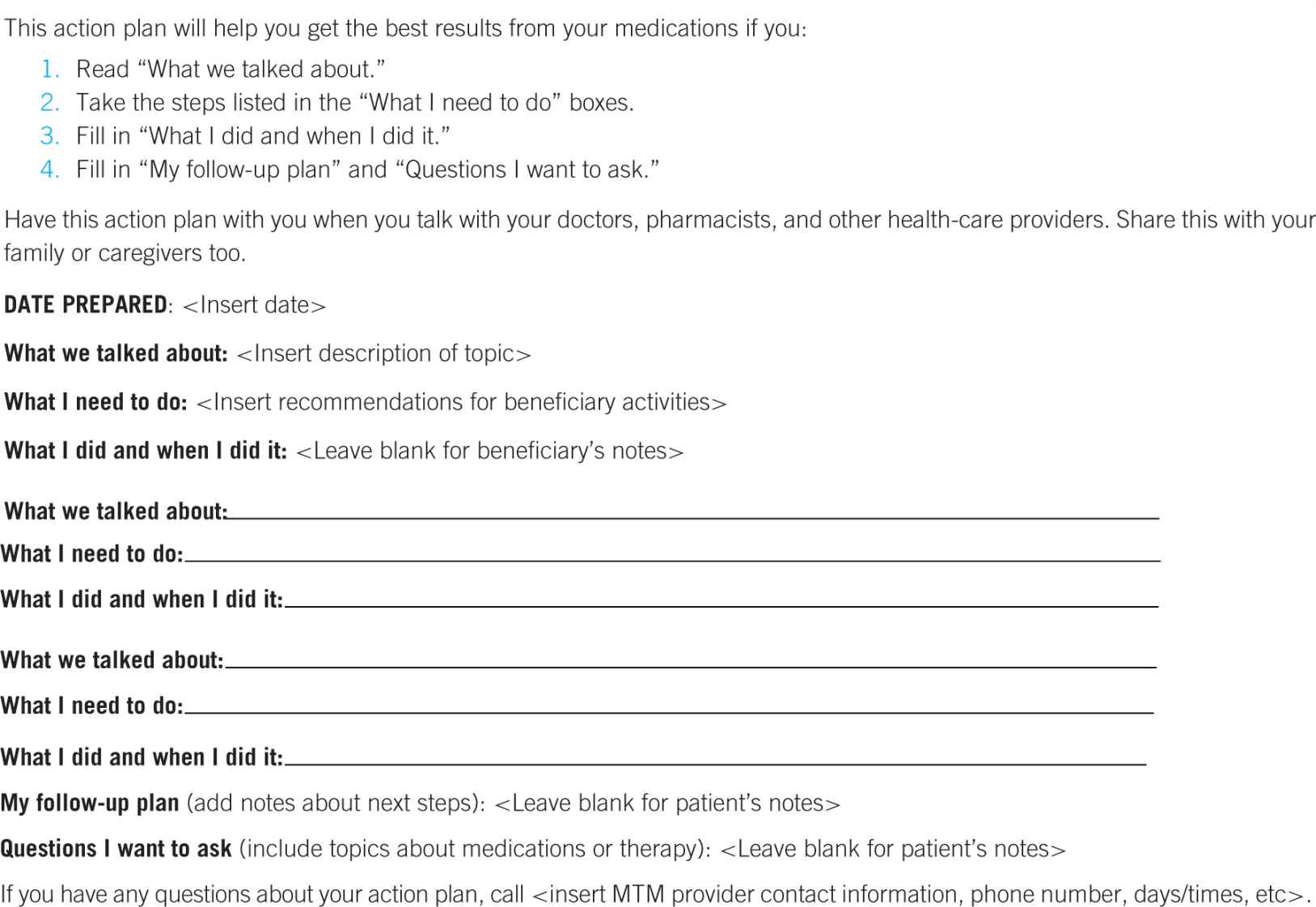

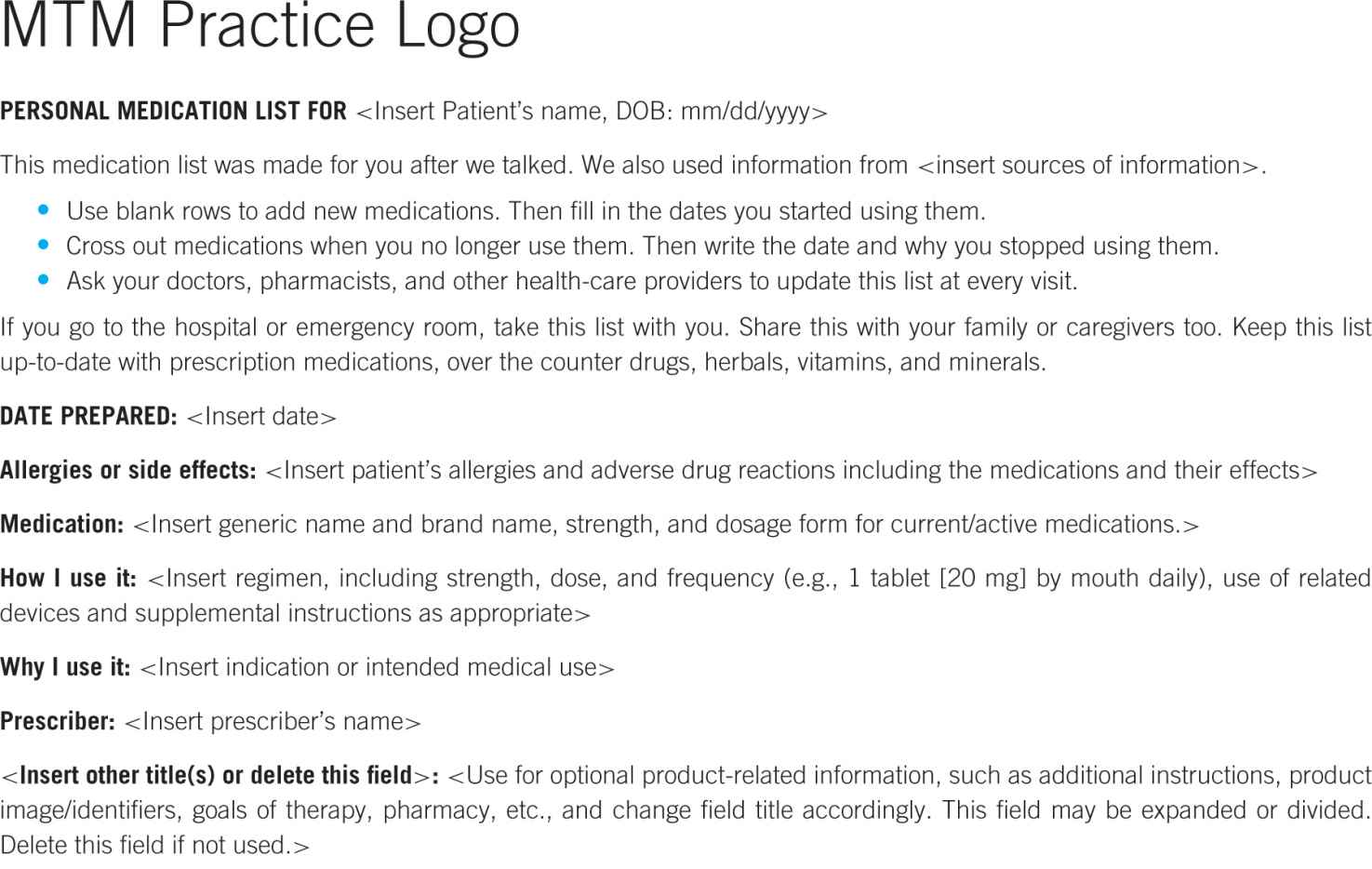

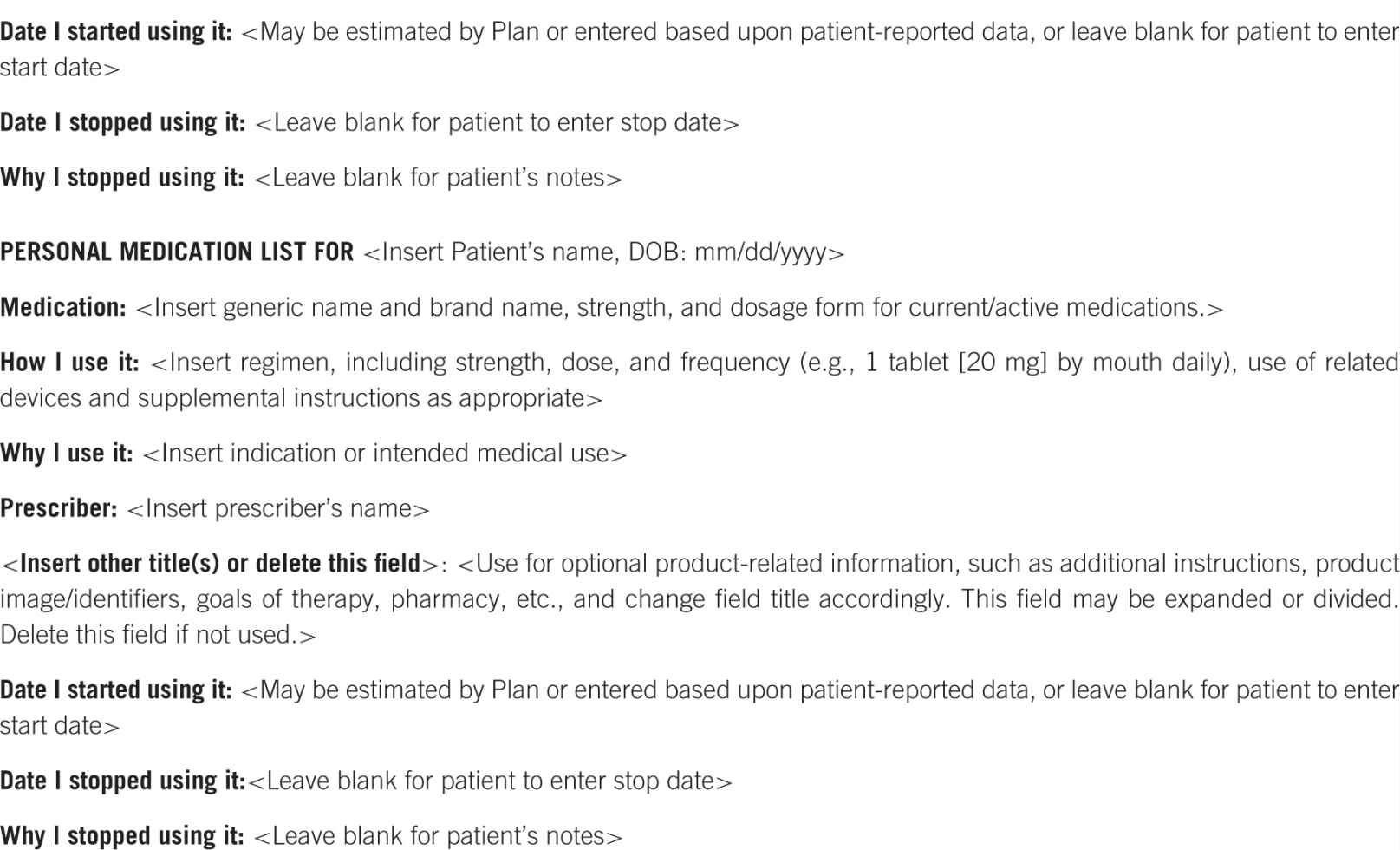

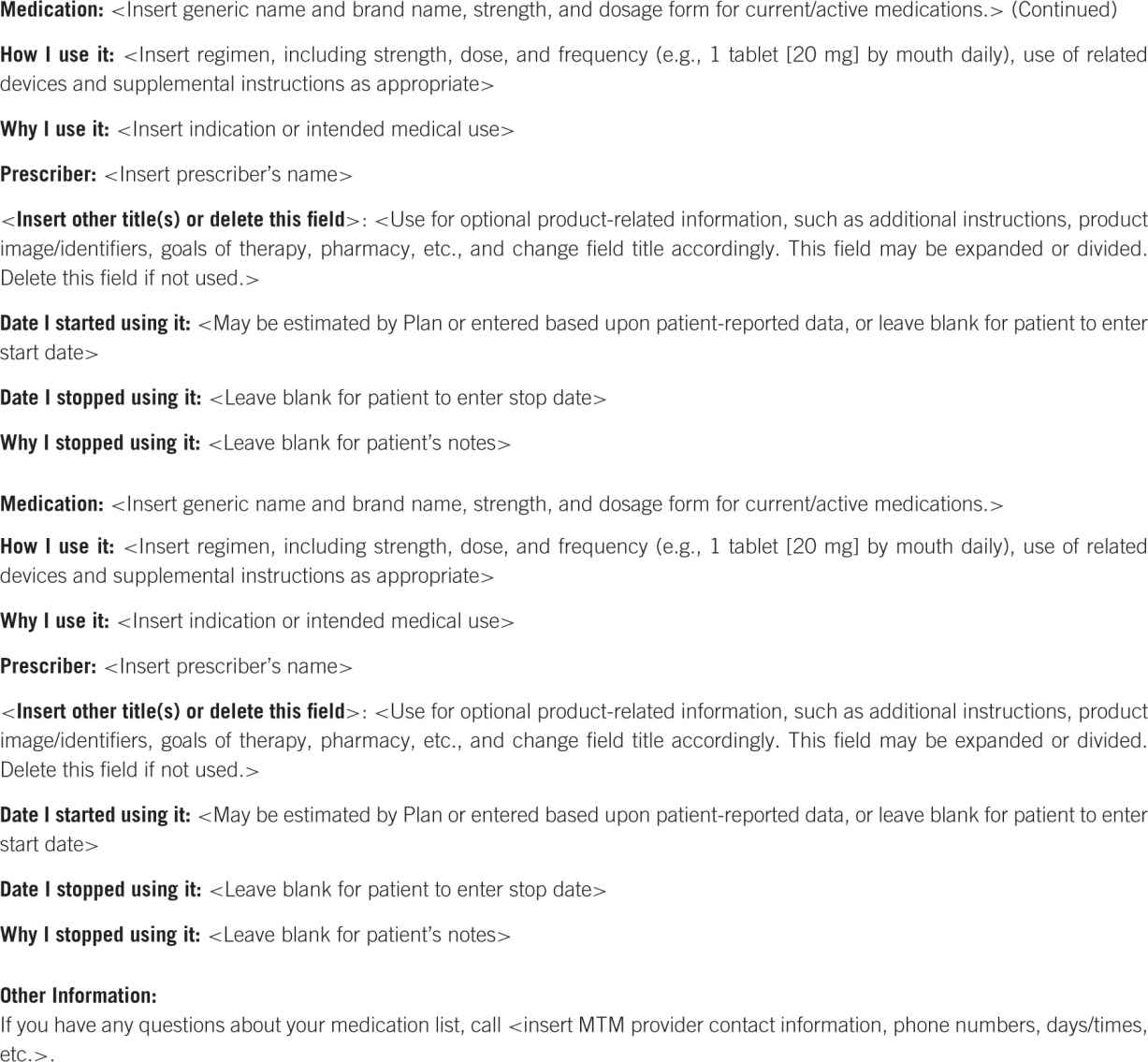

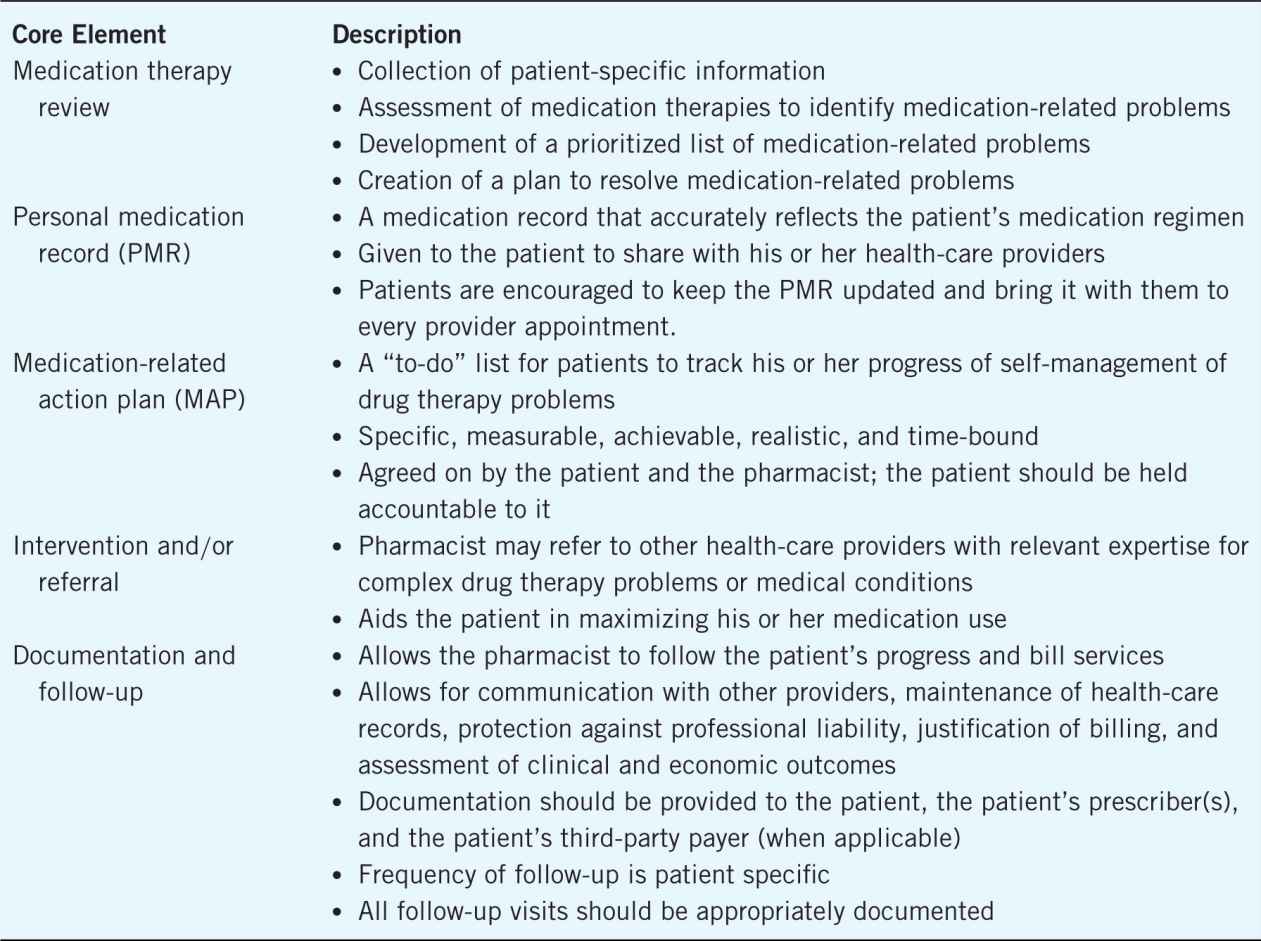

Each patient must have his or her own “chart” or record of care. This record may be integrated in to the pharmacy’s current dispensing software, or exist in a stand-alone capacity that is dedicated to the documentation of pharmaceutical care. The type of patient care service may dictate the extent of documentation. For example, state regulations very clearly dictate the patient-specific components required to be documented in a patient’s chart when pharmacists administer vaccines. Such regulations vary from state to state, but may include information about the vaccine (i.e., lot number and expiration date) in addition to demographic information of the patient and details of the service provided. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has established a standardized format for documentation for MTM programs to be enacted in January 2013.4 Examples of these formats are provided in Figures 2–1 and 2–2. Providers of MTM must provide documentation in the format dictated by CMS, and must therefore stay abreast of evolving regulations and make the necessary changes to their documentation practices.

Figure 2–1. Medication action plan (MAP) adapted to CMS requirements.4

Figure 2–2. Personal medication record (PMR) adapted to CMS requirements.4

COMPONENTS OF DOCUMENTATION

COMPONENTS OF DOCUMENTATION

In 2004, 11 associations, representing various practice niches within the profession of pharmacy, collaborated to establish a consensus definition of MTM. In this definition, entitled “Medication Therapy Management in Pharmacy Practice: Core Elements of an MTM Service Version 1.0,” components essential to an MTM encounter were defined. In 2008, version 2.0 of this guidance document was released to further assist pharmacists in executing MTM services. The core elements described serve to facilitate patient understanding of appropriate drug use, improve adherence, and detect and/or prevent adverse drug events.5

While traditional patient counseling meets expectations of licensed pharmacists, MTM services exceed expectations of licensed pharmacists by focusing on the complete medication profile of each individual patient.6,7

The core elements of an MTM service model provide guidance for pharmacists to focus on the patient as a whole through five components of care (Table 2–1).5

Table 2–1. Core Elements of MTM4

Identifying Outcomes to Track Through Documentation

The pharmacist’s role in patient care is through the identification and resolution of drug therapy problems.1 Those drug therapy problems have been classified in four categories: indication, efficacy, safety, and compliance (Table 2–2).

Table 2–2. Classification of Drug Therapy Problems1

Additionally, an estimated cost avoidance (ECA) may be assigned to the resolution of these drug therapy problems.8,9 This ECA may range from improving the quality of a patient’s care through educating them on the proper use of their medication, to avoiding a hospital admission by identifying and resolving an adverse

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree