KEY TERMS

Early successes of public health, in its mission to prevent death and disability, often came from focusing on specific diseases or groups of diseases, seeking particular causes, and finding ways to interrupt the cause-and-effect relationships. This approach was validated in the early 20th century by victories over infectious diseases. Public health professionals learned to break the chains of infection, most often by removing etiologic agents (bacteria, viruses, parasites) from the environment (water, food) or by developing vaccines to immunize potential hosts.

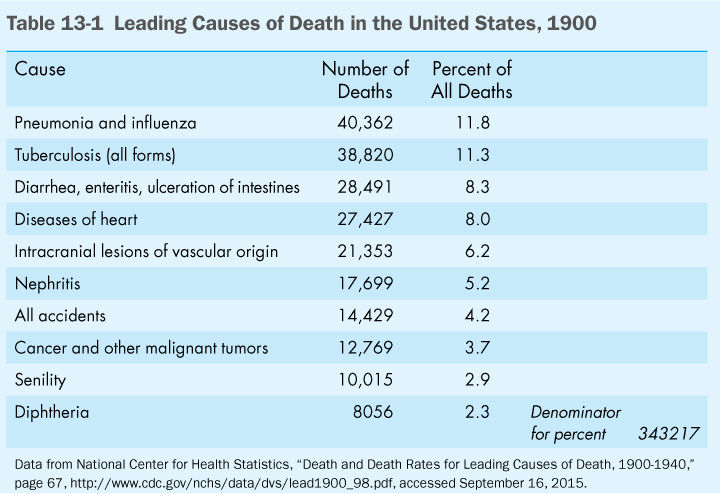

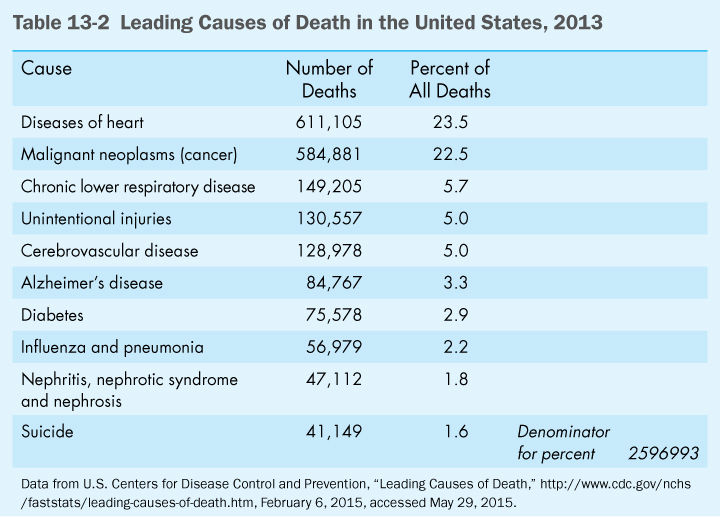

As infectious diseases were brought under control and as chronic diseases became more significant as causes of death and disability, it became increasingly apparent that the challenges faced by public health regarding chronic diseases would be more complex. Compare the leading causes of death in the United States in 1900 with those in 2013, as shown in (Table 13-1) and (Table 13-2). The top three killers of 1900, which were of infectious origin, have moved down or disappeared from the 2013 list, while heart disease has moved from fourth to first and cancer from eighth to second. The diseases at the top of the 2013 list have complex causes and most have no clear etiologic agent. Despite decades of biomedical research, there are no vaccines or environmental solutions to the problems of cancer and heart disease.

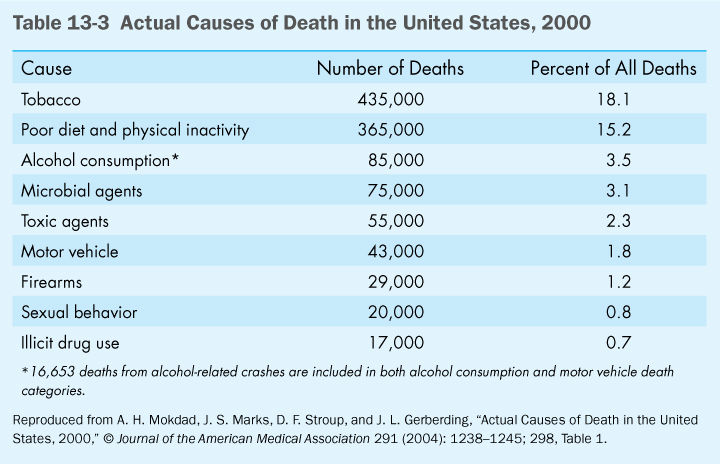

In 1990, a group of public health experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) decided that they should look at the data in a different way. They observed that the leading causes were not, in fact, root causes but were merely the diagnoses identified at the time of death. These diseases result from a combination of inborn (largely genetic) and external factors. The panel of experts undertook to identify, where possible, the underlying causes of death from each of the leading diseases. They came up with a list of nongenetic factors that they called the leading actual causes of death.1 While the mortality figures were only estimates, they were based on the best data available. These factors are highly significant for public health because they are preventable causes of death and disability and because they provide targets for public health intervention. In 2000, CDC scientists repeated the analysis with new data and found some changes, although the order of importance is almost the same.2 (Table 13-3) shows the leading actual causes of death in 2000, which are still presented as valid on the CDC’s website.3

Tobacco was found to be the leading actual cause of death in the United States. According to the study, tobacco accounts for 30 percent of all cancer deaths and 21 percent of cardiovascular disease deaths. In addition, it causes chronic obstructive lung disease, infant deaths due to low birth weight, and burns due to accidental fires. Of the 435,000 deaths attributed to tobacco smoking, 35,000 were caused by secondhand smoke.

Poor diet and physical inactivity are listed as the second most important actual cause of death. These two factors are closely related to each other, with overeating and inactivity combining to lead to obesity. Dietary fat, sedentary behavior, and obesity have all been associated with heart disease, stroke, several forms of cancer, and diabetes. The number of deaths attributed to this factor increased by 22 percent from the 1990 estimates, the largest change among all actual causes of death. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Americans increased dramatically during the 1990s and continues to increase.

In 2005, an analysis by scientists from the CDC and the National Cancer Institute found fault with the calculations of obesity as a leading cause of death.4 The new calculations, using different statistical methods, led to the conclusion that being moderately overweight was actually protective, especially in older people, although obesity still caused premature deaths. The publication of this study prompted great glee among critics of the “health police” and libertarians who object to being told what to do by the government. It is not clear why this analysis produced such different conclusions from the previous ones. In fact, the authors, troubled by the contradictions, revisited the issue in 2010, investigating several possible systematic biases that might explain them. They concluded that the differences could not be explained by illness-induced weight loss or residual confounding by smoking, and they reaffirmed the findings of the 2005 study.5 The evidence is still strong that excess weight increases risks for heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and some kinds of cancer. One possible explanation for the findings is that medical care has become increasingly effective in preventing deaths from these diseases. Despite the controversy, public health professionals continue to regard excess weight and obesity as a major threat to people’s health.

Misuse of alcohol was listed as the third actual cause of death, causing 35 percent to 40 percent of motor vehicle fatalities, as well as chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, home injuries, drowning, fire fatalities, job injuries, and 3 percent to 5 percent of cancer deaths.2 Alcohol consumption by people under 21, the legal drinking age, is associated with many health and social problems, including alcohol-impaired driving, physical fighting, poor school performance, sexual activity, and smoking. Underage drinking to excess is responsible for more than 4300 deaths in the United States each year.6

Number four on the list—microbial agents—encompasses the top three killers of 1900. The fact that mortality from infectious diseases has become so much less significant is testimony to public health’s successes. As discussed previously, however, infectious diseases have by no means been conquered, and they could move to a higher position on the list in the future.

The fact that toxic agents are listed fifth as an actual cause of death is evidence of successes in environmental health. The list’s authors call this figure the most uncertain; environmental threats may actually belong farther up the list. Certainly, environmental pollution is much more significant as a cause of death in the former Soviet Union, where environmental health has not been given the priority it has in the United States.

Firearms, sexual behavior, motor vehicles, and the illicit use of drugs round out the list. The authors, recognizing that some deaths may have multiple causes, choose what they believe to be the most significant. For example, they attribute most AIDS deaths to sexual behavior or drug use, although they recognize of course that a microbial agent is involved. The number of deaths attributed to these actual causes has declined since 1990 because of improved treatments for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Deaths from alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes have also declined since 1990, largely due to better enforcement of drunk-driving laws.2

These nine actual causes of death account for approximately 50 percent of all deaths in the United States. The other half includes genetic factors, which were specifically excluded from the analysis, and other less clearly identifiable causes. Lack of access to health care was cited as a significant factor. This problem should be alleviated by the new health care law passed during the Obama administration. Presumably, many deaths could legitimately be attributed to old age. The nine identified factors are of particular public health significance because they cause premature deaths; they are often preceded by impaired quality of life; and many could be prevented by public health measures.

In trying to prevent premature death and disability, public health must focus on these nine factors. Two of them—microbial agents and toxic agents—have traditionally been public health issues. The other seven are rooted in the behavioral choices of individuals. This is the biggest challenge now faced by public health. How can people be persuaded to behave in healthier ways in a democratic society, where every step is fraught with political, economic, and moral controversy?

There are two obvious approaches that the government has traditionally taken to promote healthy behavior: education and regulation. Both of these approaches have had successes and both have had failures. Both continue to be important components of public health’s struggle to accomplish its mission.

Education

Most simply, education informs the public about healthy and unhealthy behavior. Many people who are concerned about their health and that of their families do in fact adjust their behavior in accordance with new information. For example, the 1964 Surgeon General’s report called Smoking and Health,7 the first authoritative statement from the federal government that smoking caused cancer and other life-threatening diseases, had a significant impact on the prevalence of smoking in the United States. Many people quit the habit after learning the information, and the prevalence of smoking began to decline for the first time after 1964.

Information on healthful eating habits has traditionally been provided by the federal government. In the early 20th century, concern focused on nutritional deficiencies, and the government conducted research on requirements for various vitamins and minerals, leading to listings of recommended dietary allowances or daily values. The educational process was furthered by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements for labeling of prepared foods, which must accurately identify the percentage of the daily value provided by each serving.

While the prevention of nutritional deficiencies is still a valid concern, especially among the poor, the focus of government educational programs on nutrition has shifted to the prevention of the major killers—cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, which tend to be associated with nutritional excesses. Research over the past several decades has led to a greater understanding of the importance of overall dietary pattern in the onset of these diseases. The government’s educational efforts have stressed the importance of eating less fat (especially saturated fat), less salt, and more fruits, vegetables, and grains. The FDA has revised its labeling requirements to provide consumers with the information that will allow them to follow its guidelines. There is evidence that Americans have responded to the message that they should cut down on fat in their diet and that this behavior may have helped bring down the high rates of heart disease over the past 40 years.

Results of efforts to modify dietary and smoking behaviors, while showing some success, also illustrate the limitations of the educational approach. The impact of both messages has been limited. While the percentage of Americans who smoke has declined, almost one in five adults maintains the habit despite widespread knowledge about the dangers of tobacco.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree