Distal Splenorenal Shunts: Hemodynamics of Total Versus Selective Shunting

Atef A. Salam

This chapter can be accessed online at solution.lww.com/masteryofsurgery6e

Introduction

The goal of any portosystemic shunt is effective decompression of the gastroesophageal veins. There are two distinct types of portosystemic shunts: those that are associated with total diversion of portal blood away from the liver (i.e., total shunts), and those that maintain portal blood supply to the liver (i.e., selective shunts). Examples of total shunts include portacaval, mesocaval, and central splenorenal shunts (CSRSs). An example of a selective shunt is the distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), for which the terms selective and DSRS are often used interchangeably. The only other truly selective shunt, the coronocaval shunt, is rarely used today.

The concept of selective shunting was first introduced by Warren and his associates in 1967. These authors emphasized the increased morbidity and mortality associated with liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy after total shunting procedures. They attributed these problems to loss of liver portal perfusion. Their goal for the ideal operation for the treatment of patients with variceal bleeding was to achieve effective variceal decompression while preserving portal blood flow to the liver. The operation they devised to achieve these objectives was the DSRS.

The DSRS is created by anastomosing the splenic end of the divided splenic vein to the side of the left renal vein. The portal end of the splenic vein is oversewn. A functioning DSRS achieves variceal decompression by establishing a route for gastric venous drainage that offers less vascular resistance than the anastomotic channels between the gastric and esophageal veins. This route is sequentially made of the short gastric and splenic veins, splenorenal shunt, and left renal vein.

The second important goal of the selective shunt is to maintain portal blood flow to the liver. Because the splenorenal anastomosis is not in direct communication with the superior mesenteric or portal veins, the pressure in these vessels remains elevated. Such pressure elevation is crucial in maintaining portal blood flow to the cirrhotic liver in the face of increased vascular resistance. Portal blood flow to the liver, however, can be maintained only if the high-pressure portomesenteric venous compartment is anatomically disconnected from the low-pressure splenic venous zone. This is the rationale for combining the selective shunt with interruption of the coronary gastroepiploic and inferior mesenteric veins. Any overlooked communicating channels between these two pressure zones are likely to develop into a major conduit for diversion of portal blood away from the liver to the decompressed splenic vein.

In the early years after the introduction of the DSRS, it was the practice with my group to recommend the procedure for nearly all patients who presented with or had a documented history of variceal bleeding. The only exceptions were the patients with intractable ascites or signs and symptoms of hepatic decompensation. Increased popularity of sclerotherapy in the 1970s prompted us to conduct a prospective trial in which we compared sclerotherapy with the DSRS operation. We concluded that patients who received sclerotherapy with the DSRS as a safety net for sclerotherapy failure had better overall survival than those who received DSRS as their first line of treatment. Meanwhile, reports began to appear in the literature showing improved survival of patients with advanced liver disease treated by liver transplantation. In view of these developments, our current policy is to treat all patients initially with sclerotherapy. Patients with rebleeding after obliteration of the variceal bed are stratified according to their degree of liver function. Patients with adequate liver reserve (Child Class A or B) receive DSRS. Patients with severe liver dysfunction are evaluated for liver transplantation. Patients with intractable ascites are unsuitable for DSRS. Patients with bleeding gastric varices who are good operative candidates are considered for DSRS as initial treatment because these varices are difficult to sclerose.

Preoperative evaluation for DSRS should include liver function tests, liver serologic evaluation, splenoportography, and left renal venography. Hepatic wedge venography and pressure measurement are useful in differentiating between presinusoidal and postsinusoidal portal hypertension. An angiographic evaluation of the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins is indicated in patients with Budd–Chiari syndrome. Liver ultrasonography or computed tomographic scanning is used to determine the liver volume and to uncover nodules that may suggest hepatoma formation. Such nodules should be subjected to biopsy preoperatively for histologic verification. Liver biopsy is also indicated to determine the nature of the underlying liver disease in atypical cases and in patients with clinical evidence of active viral or alcohol-related liver disease.

It is our policy to postpone the operation until the liver function and nutritional status of the patient are maximally improved. Patients who are actively drinking alcohol are referred to appropriate centers, and the operation is deferred until there is a reasonable chance that they will abstain. Patients with ascites are treated medically until the problem is resolved. Intractable ascites is a contraindication to DSRS operation.

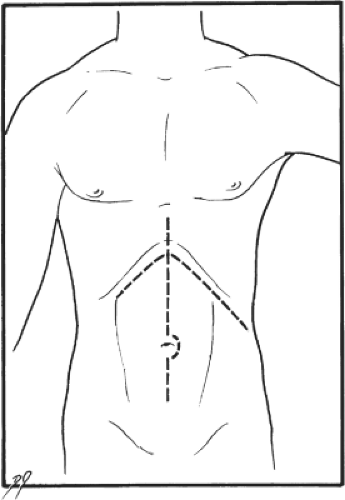

The patient is placed in the supine position. Slight hyperextension of the lumbar spine helps improve surgical exposure. The procedure is most commonly performed from a subcostal incision. The incision begins in the left midaxillary line and extends one fingerbreadth below the costal margin, across the midline, to the lateral border of the right rectus muscle. This incision provides excellent exposure, particularly to the region of the tail of the pancreas and hilum of the spleen. It may, however, weaken the abdominal wall. The midline incision (Fig. 1) is also adequate for this procedure and has, in fact, become my preference in recent years. In the patients who have previously undergone midline abdominal operations, fewer adhesions may be encountered if the subcostal incision is used. Abnormal bleeding from the skin edges and abdominal muscles is common in patients with portal hypertension. Well-developed venous collaterals are often encountered around the umbilicus and in the falciform ligament. All

bleeding should be securely controlled before proceeding with the operation. Persistent incisional bleeding can cause considerable perioperative blood loss in patients with portal hypertension. Another potential source of bleeding in these patients is the portosystemic collateral veins, which form in the adhesions between the abdominal contents and the abdominal wall. These adhesions should be meticulously divided by appropriate hemostatic techniques.

bleeding should be securely controlled before proceeding with the operation. Persistent incisional bleeding can cause considerable perioperative blood loss in patients with portal hypertension. Another potential source of bleeding in these patients is the portosystemic collateral veins, which form in the adhesions between the abdominal contents and the abdominal wall. These adhesions should be meticulously divided by appropriate hemostatic techniques.

Fig. 1. Bilateral subcostal and midline incisions, both suitable for the distal splenorenal shunt operation. |

After all the adhesions crossing the surgical field are lysed, the abdomen is explored. Any suspicious nodule in the liver is sampled and examined for malignancy. The gallbladder is palpated for stones. In patients with cirrhosis, one should avoid cholecystectomy if at all possible. The morbidity and mortality from this procedure are quite high in such patients. Enlargement of the gallbladder is common among these patients, and this finding should not be mistaken for acute obstructive cholecystitis unless there are obvious signs of acute inflammation.

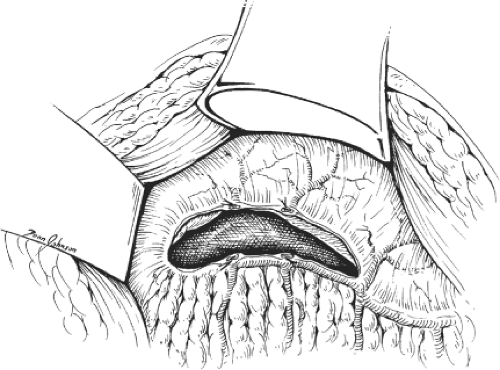

Adequate exposure is of crucial importance in the DSRS operation because of the depth of the operative field. In our experience, the Omni retractor is extremely useful for this purpose, particularly during dissection of the splenic and left renal veins. It should be remembered, however, that the tissues of patients with portal hypertension are congested and, if injured, can cause troublesome bleeding. This fact is especially true for the mesentery and spleen. Thus, it is important to use gentle retraction and to use proper padding under the retractor blades. The next step is to proceed with devascularization along the greater curvature of the stomach (Fig. 2). The gastric vessels are isolated individually, then divided between clamps and ligated according to proper surgical techniques. Devascularization is carried close to the wall of the stomach in a stretch extending from the pylorus to the first short gastric vein. The right and left gastroepiploic veins are suture-ligated for the aforementioned reasons. Next, the splenic flexure is carefully mobilized by dividing its peritoneal attachment to the lower pole of the spleen. The stomach is then retracted superiorly, and the transverse colon is retracted inferiorly, using appropriate retractor blades. This procedure brings the pancreas into view. The stage is now ready for exposure of the splenic vein.

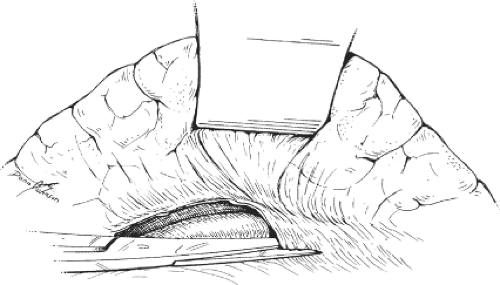

We routinely use headlight and magnifying loupes for mobilization of the splenic vein. First, the pancreas is mobilized by dividing the peritoneum along its inferior border (Fig. 3). Mobilization of this border is completed before dissection is carried deeper in the retropancreatic space. With the pancreas carefully retracted, the surgeon starts looking for the splenic vein. In most instances, it loops inferiorly as it approaches the superior mesenteric vein. It is, therefore, easier to identify the splenic vein first medially, then to proceed with its mobilization in the direction of the hilum of the spleen. The inferior mesenteric veins may be used as a guide to find the splenic vein unless it is joining the superior mesenteric vein (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. The posterior peritoneum is divided along the lower border of the pancreas. The latter is retracted gently to visualize the splenic vein. |

The splenic vein should be mobilized first inferiorly, then anteriorly, and posteriorly, leaving dissection of its superior border until adequate length of the vein has

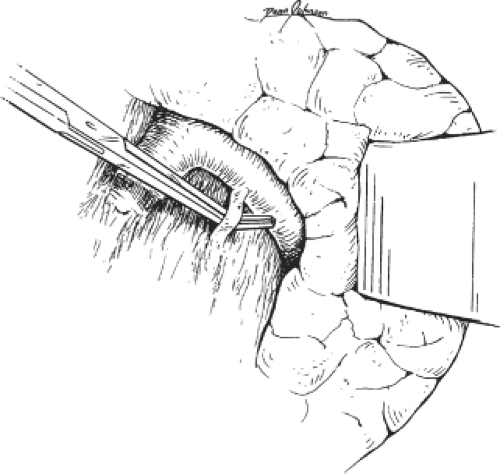

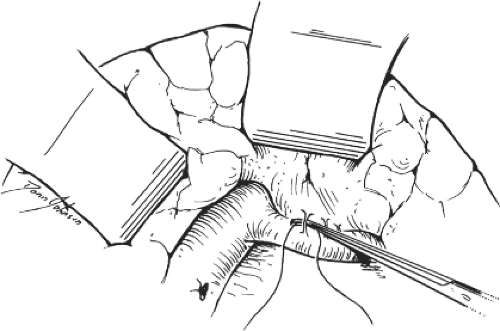

been exposed. The pancreatic veins along this border of the pancreas require special handling because they are friable and, if torn, can cause troublesome bleeding. Our technique for isolation of these veins starts with careful dissection until a sufficient length of the vein is exposed. A fine silk suture is then applied around the mobilized vein and ligated flush with the splenic vein. A fine-tip clamp is applied to the other side, and the vein is transected between the clamps. The pancreatic end of the divided vessel is then ligated using meticulous surgical technique (Fig. 5). These veins are sometimes too short to be safely controlled with simple ligatures, in which case it is safer to use 5-0 Prolene to suture the divided veins. Dissection of the pancreatic veins is the most challenging part of the DSRS operation. In my experience, the tearing of these vessels is most often caused by excessive pancreatic retraction, a premature attempt to encircle the splenic vein, or a premature attempt to encircle the pancreatic veins. Another complicating factor in this dissection is the coronary vein, which joins the upper border of the splenic vein in approximately one-fifth of the patients. In some cases, the coronary vein may be as large as the splenic vein. Tearing of the coronary vein can cause severe bleeding and may lead to irreversible damage to the splenic vein. The safest way to deal with this situation is to free the upper border of the splenic vein and encircle it on both sides of the coronosplenic venous junction. Gentle traction on the splenic vein facilitates further mobilization of the coronary vein (Fig. 6). The mobilization is continued until there is sufficient room for safe clamping and division of the coronary vein.

been exposed. The pancreatic veins along this border of the pancreas require special handling because they are friable and, if torn, can cause troublesome bleeding. Our technique for isolation of these veins starts with careful dissection until a sufficient length of the vein is exposed. A fine silk suture is then applied around the mobilized vein and ligated flush with the splenic vein. A fine-tip clamp is applied to the other side, and the vein is transected between the clamps. The pancreatic end of the divided vessel is then ligated using meticulous surgical technique (Fig. 5). These veins are sometimes too short to be safely controlled with simple ligatures, in which case it is safer to use 5-0 Prolene to suture the divided veins. Dissection of the pancreatic veins is the most challenging part of the DSRS operation. In my experience, the tearing of these vessels is most often caused by excessive pancreatic retraction, a premature attempt to encircle the splenic vein, or a premature attempt to encircle the pancreatic veins. Another complicating factor in this dissection is the coronary vein, which joins the upper border of the splenic vein in approximately one-fifth of the patients. In some cases, the coronary vein may be as large as the splenic vein. Tearing of the coronary vein can cause severe bleeding and may lead to irreversible damage to the splenic vein. The safest way to deal with this situation is to free the upper border of the splenic vein and encircle it on both sides of the coronosplenic venous junction. Gentle traction on the splenic vein facilitates further mobilization of the coronary vein (Fig. 6). The mobilization is continued until there is sufficient room for safe clamping and division of the coronary vein.

Fig. 4. The inferior mesenteric vein is identified in preparation for its division. In some cases, the inferior mesenteric vein is used as a guide for the splenic vein. |

Fig. 5. Technique for isolation and division of the pancreatic veins. These veins are encircled, ligated, and then divided using meticulous surgical technique. Laceration of these fragile veins causes troublesome bleeding.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|