CHAPTER

5

DISPENSING CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

Upon completing this chapter, the reader will be able to:

▶ Understand the “legitimate medical purpose” and “corresponding responsibility” doctrine and the application to pharmacy practice.

▶ Identify the dispensing requirements for each schedule of controlled substances.

▶ Describe the function and execution procedures of Drug Enforcement Administration Order Form 222.

▶ Recognize the recordkeeping requirements under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA).

As guardians of the nation’s drug supply, pharmacists have a responsibility to ensure that, among other things, controlled substances are not diverted outside the distribution system. This chapter outlines the CSA’s requirements for dispensing of controlled substances to patients, including the documentation requirements necessary to ensure accountability of dispensers for the controlled substances they have acquired and distributed.

The regulations provide specific requirements for the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substance prescriptions. A prescription is defined as

an order for medication which is dispensed to or for an ultimate user but does not include an order for medication which is dispensed for immediate administration to the ultimate user (e.g., an order to dispense a drug to a bed patient for immediate administration in a hospital is not a prescription). (21 C.F.R. § 1300.01(b)(35))

Thus a medication order in a hospital or other institution is not a prescription. Most state laws also recognize this distinction, which is very important for hospital pharmacies. If a medication order is not a prescription, then the pharmacy does not have to comply with all the strict recordkeeping, labeling, and other requirements applicable to either a controlled substance prescription or a noncontrolled substance prescription for that matter. Thus, for example, unless state law provides otherwise, medication orders do not have to be on a security prescription blank, and the order and label would not have to contain all the information required of a prescription.

The requirement that a prescription must be for an ultimate user precludes individual practitioners from writing controlled substance prescriptions for office use. If this is not clear enough, the regulations also state:

A prescription may not be issued in order for an individual practitioner to obtain controlled substances for supplying the individual practitioner for the purpose of general dispensing to patients. (21 C.F.R. § 1306.04(b))

A pharmacist who knowingly fills such a prescription would be dispensing a controlled substance pursuant to an invalid prescription and would be in violation of the law.

THOSE ALLOWED TO PRESCRIBE CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

A prescription for a controlled substance may be issued only by an individual practitioner who is both (1) authorized to prescribe controlled substances in the state in which he or she is licensed to practice and (2) registered or exempt from registration under the CSA (21 C.F.R. § 1306.03).

The definition of individual practitioners includes physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and others authorized in their appropriate jurisdiction to dispense controlled substances. The term also includes those individuals the regulations call mid-level practitioners (e.g., nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, physician assistants, pharmacists). In some states, these individuals are authorized to prescribe controlled substances. (Note: No state grants pharmacists true general prescriptive authority because pharmacists must be dependent on collaborative practice agreements.) Pharmacists in those states must know state law to determine which nurse practitioners and physician assistants can prescribe controlled substances and the scope of their prescriptive authority. Some states grant these practitioners the authority to prescribe only certain controlled drugs or only certain classes of controlled substances. Some states grant authority only in institutional settings and under protocol. Some states have other restrictions, and some states have none.

Although only an individual practitioner can issue a controlled substance prescription, an employee or agent of the individual practitioner may communicate it to a pharmacist (21 C.F.R. § 1306.03(b)). Furthermore, a secretary or agent may prepare the prescription for the individual practitioner’s signature (21 C.F.R. § 1306.05(a)).

An individual practitioner may not delegate his or her prescriptive authority to an agent unless that agent has been granted prescriptive authority under state law. In practice, pharmacists who call for refill authorization often find it difficult to determine if the individual practitioner has actually authorized the refill. Some situations are obvious, such as when the pharmacist calls for authorization and the office nurse, without hesitation, indicates the refill is permitted. Most likely the nurse has not communicated with the prescriber, and the pharmacist has a duty to ascertain who is really authorizing the refill. Most situations are not so obvious, however. When the prescriber’s agent calls the pharmacist back several minutes later to authorize the refill, for example, the pharmacist can usually assume that the individual practitioner has indeed authorized the refill. The same would apply to voice mail and fax responses from the prescriber’s office.

When confronted with a suspicious controlled substance prescription, as occasionally happens, a pharmacist may try to determine whether the prescription is fraudulent by checking the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registration number of the prescriber when the number is not known to the pharmacist. A DEA registration number is a nine-character number consisting of two alphabet letters followed by seven digits. Initially, registration numbers for practitioners registered as dispensers began with the letter A. After all registration numbers starting with A had been assigned, the DEA started new dispenser registration numbers with the letter B. Ultimately all B numbers were exhausted and new practitioner registrants then received a number starting with the letter F. More recently, the DEA also began utilizing the letter G. Registration numbers for mid-level practitioners begin with an M. Distributor registration numbers begin with a P or an R; once the R numbers are exhausted, a new initial letter will be chosen.

The second letter in the registration number is usually, but not always, the first letter of the registrant’s last name. If the registrant is a business and the business name begins with a number, the second space contains a number. The next six positions represent a computer-generated number unique to each registrant. The last and ninth position is a computer-calculated check digit and a key to verifying the number.

To check the validity of a DEA registration number, a pharmacist

1. Adds the first, third, and fifth digits

2. Adds the sum of the second, fourth, and sixth digits, multiplied by 2, to the first sum

3. Determines if the right-most digit of this sum corresponds with the ninth check digit

For example, to check the validity of hypothetical registration number AN1257218 for Dr. Bill Nash, a pharmacist adds the first, third, and fifth digits:

1 + 5 + 2 = 8

Next, the second, fourth, and sixth digits are added and multiplied by 2:

(2 + 7 + 1) × 2 = 20

The sum of 20 and 8 equals 28.

The right-most digit, 8, corresponds to the ninth digit of the registration number. Thus, the number could be valid.

In reality, many forgers are familiar with the procedure to verify a DEA registration number and can invent a number that would be plausible. Therefore, pharmacists cannot rely on this check alone to determine the validity of a controlled substance prescription. As a better alternative to verifying a DEA registration, the DEA provides a list of active DEA registrants to the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), a component of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The database of active DEA registrants may be obtained from NTIS as a single purchase or subscribed to on a monthly or quarterly basis (NTIS can be reached by calling 800-363-2068 or online at http://www.ntis.gov/products/dea.aspx.)

THOSE ALLOWED TO DISPENSE CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

Only a pharmacist who is acting in the usual course of professional practice and who either is registered individually or is employed by a registered pharmacy or registered institutional practitioner may fill a prescription for a controlled substance (21 C.F.R. § 1306.06). A pharmacist is defined as a person licensed by a state to dispense controlled substances, as well as any other person (e.g., pharmacist intern) authorized to dispense controlled substances under the supervision of a pharmacist. Whether pharmacy technicians or other ancillary personnel may engage in dispensing controlled substances under the supervision of a pharmacist depends on state law. Individual practitioners also may dispense if authorized by state law.

All controlled substance prescriptions issued by an individual practitioner must be dated as of the date of issuance; in other words, a prescriber may not predate or postdate prescriptions. In addition to the date of issuance, all controlled substance prescriptions must contain at least the following information (21 C.F.R. § 1306.05):

• The full name and address of the patient

• The name, address, and registration number of the practitioner

• The drug name, strength, dosage form

• The number of units or volume dispensed

• Directions for use

A prescription issued pursuant to the Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) must also contain the physician’s special DEA number (DATA 2000 waiver ID or “X” number) or a written notice that the physician is acting in “good faith” while waiting for the identification number to be issued. A prescription written for gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid must include the medical need of the patient written on the prescription. The regulation establishes a “corresponding liability” on the pharmacist to ensure that the prescription is prepared properly.

The prescriber must sign written controlled substance prescriptions on the day of issuance. When oral orders are not permitted, the prescription must be written in ink or indelible pencil, or typewritten, and manually signed by the prescriber. A computergenerated prescription that is printed out or faxed by the prescriber must be manually signed. If the pharmacist receives the prescription orally, the pharmacist may write in the name of the prescriber. Electronic controlled substance prescriptions must comply with DEA regulations summarized later in this chapter.

Although the prescriber’s agent may prepare the prescriptions for the prescriber’s signature, it is the responsibility of both the individual practitioner and the pharmacist to ensure that the prescriptions conform to all essential aspects of the law and regulations.

Individual practitioners exempt from registration must include on the prescriptions the registration number of the hospital or other institution at which they practice and the special internal code number assigned to them by the hospital or institution (21 C.F.R. § 1306.05(b)). Each written prescription must have the name of the physician stamped, typed, or hand printed on it, as well as the signature of the physician. Those exempt from registration because they are members of the armed services or public health service must include on each prescription their service identification number in lieu of the registration number (21 C.F.R. § 1306.05(c)).

Before filing the prescription in the pharmacy, regulations also require the prescription to contain the written or typewritten name or initials of the pharmacist dispensing the drug (21 C.F.R. § 1304.22(c)).

Correcting a Written Controlled Substance Prescription

Occasionally, pharmacies receive controlled substance prescriptions that are incomplete or that contain errors and the question becomes whether the pharmacist can legally correct the prescription. Regarding schedule III, IV, or V prescriptions, the DEA has provided a clear answer at its website: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/faq/prescriptions.htm#rx-8. If the prescription does not contain the patient’s address or contains an incorrect address, the pharmacist may add or correct the address upon verification. The pharmacist may also add or change the dosage form, drug strength, drug quantity, directions for use, or issue date after consultation with and agreement of the prescriber and after documentation on the prescription. The pharmacist is never permitted to make changes to the patient’s name, controlled substance prescribed (except for generic substitution), or the prescriber’s signature. Of course, a pharmacist may contact the prescriber and simply convert the written prescription to an oral one if any of this information does need to be changed or added. It is also important for pharmacists to keep up to date on state law or guidance on this matter and to follow state requirements if they are stricter.

Whether a pharmacist can correct a schedule II prescription has involved conflicting opinions from the DEA and has created considerable controversy. Prior to 2009, the DEA’s website had provided that a pharmacist could essentially correct a schedule II prescription in the same manner as a schedule III, IV, or V prescription. However, in the preamble to a regulation enacted in November 2007 entitled “Multiple Prescriptions for Schedule II Controlled Substances” (discussed under “Multiple Schedule II Prescriptions for the Same Drug and Patient Written on the Same Day”), the DEA stated that the “essential elements of the [schedule II] prescription written by the practitioner (such as the name of the controlled substance, strength, dosage form, and quantity prescribed) … may not be modified orally.”

In October 2008, the DEA issued a policy statement that it recognized the conflict and instructed pharmacists to follow state regulations or policy until the DEA could resolve this issue by regulation. Subsequently, some time in 2009 and without notice, the DEA withdrew its original policy statement (that permitted correcting schedule II prescriptions) from the website and replaced it with the statement from the preamble to the regulation stating that schedule II prescriptions may not be corrected. The healthcare community complained vigorously and the DEA appeared to have listened. A few months later, in 2010, the DEA again reversed its position and changed its website, instructing pharmacists to follow state law or policy regarding whether they can correct a schedule II prescription (available at http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/faq/prescriptions.htm#rx-8). However, the DEA then proceeded to further confuse the matter by issuing a letter in late 2010 to a pharmacy audit firm stating that the pharmacist is not an agent of the prescriber for the purposes of adding the prescriber’s DEA registration number on the written prescription. (Letter from Mark Caverly, Chief Liaison and Policy Section, Office of Diversion Control, to Rena Bielinski, Chief Pharmacy Officer, National Audit (Nov. 1, 2010)).

This letter raised the question of whether the DEA had again changed its mind, believing that a pharmacist is not an agent and thus cannot make any changes. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) then requested a clarification on the DEA’s policy in July 2011. In August 2011, the DEA issued a letter to NABP stating that whether it is appropriate for pharmacists to make changes in a schedule II prescription varies on a case-by-case basis; and, that a pharmacist should exercise professional judgment and knowledge of state and federal laws to make a decision. (Letter from Joseph Rannazzisi, Deputy Assistant Administrator, Office of Diversion Control, to Carmen Catizone, NABP (Aug. 24, 2011), available at http://www.nabp.net/news/assets/DEA-missing-info-schedule-2.pdf). It thus seems at this time that pharmacists can make corrections if state law or policy allows.

PURPOSE OF A CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE PRESCRIPTION

Federal regulations provide as follows:

A prescription for a controlled substance to be effective must be issued for a legitimate medical purpose by an individual practitioner acting in the usual course of his professional practice. The responsibility for the proper prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances is upon the prescribing practitioner, but a corresponding responsibility rests with the pharmacist who fills the prescription. An order purporting to be a prescription issued not in the usual course of professional treatment or in legitimate and authorized research is not a prescription within the meaning and intent of Section 309 of the Act (21 U.S.C. § 829) and the person knowingly filling such a purported prescription, as well as the person issuing it, shall be subject to the penalties provided for violations of the provisions of law relating to controlled substances. (21 C.F.R. § 1306.04(a))

Corresponding Responsibility Doctrine

The preceding regulation, referred to as the corresponding responsibility doctrine, clearly indicates that both the prescriber and the pharmacist are legally responsible for the proper prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances. Therefore, pharmacists must be particularly alert that the controlled substance prescriptions they receive and dispense are for a legitimate medical purpose and are issued by a lawful practitioner in the usual course of professional practice.

Defining “Knowingly”

The corresponding responsibility doctrine is not absolute because the regulation states that a violation occurs when the pharmacist “knowingly” dispenses an improper prescription. Thus, the definition of “knowingly” is critical because a pharmacist who does not know a prescription is not for a legitimate medical purpose cannot have violated the regulation. In other words, a pharmacist should not be accountable for filling an invalid prescription that the pharmacist could not have known was invalid.

In United States v. Hayes, 595 F.2d 258 (5th Cir. 1979), included in the case studies section of this chapter, a pharmacist challenged the constitutionality of the corresponding responsibility doctrine, contending that the doctrine imposes an unfair burden on pharmacists because they cannot prescribe and do not have the means of knowing if a prescription is really valid. The most that a pharmacist can do, argued the pharmacist, is to call the physician and seek verification of the prescription, which he did. The facts of the case indicate that the pharmacist dispensed a tremendous number of prescriptions from a single physician for massive quantities of drugs to patients who admitted selling the drugs. The court rejected the constitutional argument, essentially finding that the regulation does not impose an unattainable obligation on pharmacists. However, the court added, verification of a prescription may not in itself be enough to establish that the pharmacist has met the knowledge requirement in situations such as this where the prescriptions are obviously false. Thus, the court disagreed with the pharmacist and affirmed his conviction.

In a similar case, United States v. Lawson, 682 F.2d 480 (4th Cir. 1982), a physician who operated a diet clinic created medical records for fictitious patients and sold prescriptions written for Preludin and Tuinal for these fictitious patients to an obese patient. The patient would then present the prescriptions to the defendant pharmacist, Lawson. Initially, Lawson had contacted the physician to ascertain the validity of the prescriptions, but he subsequently dispensed the prescribed drugs without question.

Lawson was charged with dispensing schedule II drugs that he knew were not for a legitimate medical purpose. He contended that he did not know the prescriptions were not for a legitimate medical purpose. The court, however, convicted Lawson, finding that he should have known for a number of reasons. First, one person was presenting a large number of prescriptions, all written by one physician. Second, the prescriptions were uniform in dosages and quantities. Third, the sudden surge in the quantity of prescriptions for the controlled substances should have been suspect. The appellate court confirmed Lawson’s conviction.

The court’s opinion in a California case, Vermont & 110th Medical Arts Pharmacy v. State Board of Pharmacy, 177 Cal. Rptr. 807 (Cal. Ct. App. 1981), states the pharmacist’s responsibility very well. In this case, over a 45-day period, the pharmacy filled 10,000 prescriptions written by a small group of physicians for four controlled substances. All together, these prescriptions accounted for 748,000 dosage units. Many of these prescriptions were filled in consecutively numbered batches for the same prescriber and for the same person with different addresses, although many of the addresses were nonexistent. Many of the names were suspect as well (e.g., Henry Ford, Fairlane Ford, Glenn Ford, Pearl Harbor). In response to the pharmacist’s argument that he did not know the prescriptions were not valid, the court replied:

The statutory scheme plainly calls upon pharmacists to use their common sense and professional judgment. When their suspicions are aroused as reasonable professional persons by either ambiguities in the prescriptions, the sheer volume of controlled substances prescribed by a single practitioner for a small number of persons or, as in this case, when the control inherent in the prescription process is blatantly mocked by its obvious abuse as a means to dispense an inordinate and incredible amount of drugs under the color and protection of the law, pharmacists are called upon to obey the law and refuse to dispense. (177 Cal. Rptr. at 810)

These cases indicate that whether a pharmacist knew that prescriptions were not for a legitimate medical purpose can be inferred from strong circumstantial evidence. Thus, for criminal purposes, “knowingly” could be defined as when a pharmacist should have known based on obvious facts but rather consciously chose to disregard them. Stated another way, the pharmacist recognized the possibility of wrongdoing but consciously refused to conduct a proper investigation. A pharmacist is expected to exercise professional judgment when suspicions should arise and should take action to determine if the prescription is valid. In these situations, verification with the prescriber is a critical first step; this step may not be enough, however, when facts indicate that the pharmacist should have investigated further.

On the other hand, although pharmacists must be ever vigilant for invalid prescriptions, they also must guard against being overly suspicious. In the case of Ryan v. Dan’s Food Stores, Inc., 972 P.2d 395 (Utah 1998), reported in the case studies section of this chapter, a pharmacist contended that he was wrongfully discharged for questioning the validity of controlled substance prescriptions. The court, however, found the discharge to be valid because the discharge was based on the pharmacist’s behavior of being suspicious of most of the patients with controlled substance prescriptions and of being rude to those patients. The Ryan case is a good example that a pharmacist should not be suspicious of a patient unless the pharmacist has a reason to be suspicious. Without any indication to the contrary, a pharmacist should presume that a controlled substance is legitimate. The Gordon v. Frost case, 388 S.E.2d 362 (Ga. 1989), also reported in the case studies section, demonstrates the civil liability consequences of a pharmacist who was overly suspicious and “jumped to the conclusion” that a regular patient was attempting to fraudulently obtain a refill of a controlled substance prescription.

Legitimate Medical Purpose and Usual Course of Professional Practice

Only prescriptions written for a “legitimate medical purpose” in the “usual course of professional practice” are valid under the law. Although these terms are not specifically defined, at least one court has found the term to mean acting “in accordance with a standard of medical practice generally recognized and accepted in the United States” (United States v. Moore, 423 U.S. 122, 139 (1975)). Some examples of invalid controlled substance prescriptions not written for a legitimate medical purpose include

• Fraudulent or forged prescriptions written by persons not authorized to issue drug orders

• Prescriptions written by individual practitioners for office use

• Prescriptions written by individual practitioners: ° For fictitious patients

° For patients not named on the prescription

° When the individual practitioner has not performed a good-faith medical examination

° When there is no medical reason for the prescription

• Narcotic prescriptions written by individual practitioners to maintain an addiction or to detoxify an addict

• Prescriptions written by individual practitioners that exceed the usual course of their professional practice; for example, a dentist who prescribes a controlled drug for a patient’s back pain unrelated to dental diagnosis

This list clearly demonstrates that facial validity of a prescription does not in itself make a prescription valid. A controlled substance prescription must be based on a legitimate physician–patient relationship, where the prescriber has taken a patient history, conducted an assessment, developed a treatment plan, and documented these steps. As will be discussed under “Internet Pharmacy Prescriptions,” the CSA was amended to provide that when controlled substances are dispensed via the Internet, a valid prescription requires the practitioner to have conducted at least one in-person medical evaluation of the patient. This means a good-faith examination in compliance with standards of practice. Although this amendment applies to Internet pharmacy, the requirement is no less applicable to every controlled substance prescription in any practice setting. Courts will consider if a situation violates “legitimate medical purpose” and “usual course of professional practice” on a case-by-case basis. However, cases where courts have determined that violations occurred have been based upon blatant or glaring misconduct, not merely questionable legality (United States v. Rosen, 582 F.2d 1032 (5th Cir. 1978)).

The DEA has published a guide, titled A Pharmacist’s Guide to Prescription Fraud, to help pharmacists ensure that controlled substance prescriptions are being issued for a legitimate medical purpose. The guide can be found at http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/brochures/pharmguide.htm (or in Appendix D of the 2010 Pharmacist’s Manual at http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/index.html) and includes some situations that should make pharmacists suspicious, such as:

• The prescriber writes significantly larger numbers of prescription orders (or in larger quantities) compared with other practitioners in your area.

• The prescriber writes for antagonistic drugs, such as depressants and stimulants, at the same time. Drug abusers often request prescription orders for “uppers and downers” at the same time.

• Patients appear to be returning too frequently. For example, a prescription that should have lasted for a month is being refilled weekly.

• Patients appear presenting prescription orders written in the names of other people.

• A number of people appear simultaneously, or within a short time, all bearing similar prescription orders from the same practitioner.

• Numerous “strangers,” people who are not regular patrons or residents of your community, suddenly show up with prescription orders from the same physician.

The guide urges pharmacists to contact the state board of pharmacy or local DEA office if they think they may have discovered a pattern of prescription abuses.

More recently, the NABP released an educational video on May 27, 2014, entitled “Red Flags.” Red flags are considered circumstances surrounding the presentation of a controlled substance prescription that should raise reasonable suspicion about the validity of that prescription. The video was sponsored by the Anti-Diversion Industry Working Group and was produced to assist pharmacists in properly exercising their corresponding responsibility and identifying the warning signs of prescription drug abuse and diversion. Additional information about the video, including a link to it, is available on the NABP website at http://www.nabp.net/news/new-educational-video-for-pharmacists-addresses-prescription-drug-abuse.

Exercise of Clinical Judgment and the Treatment of Pain

The treatment of pain with controlled substances is unquestionably a legitimate medical purpose. Pharmacists must take care that the legitimate medical purpose rule not be misapplied to determining the appropriateness of the drug therapy. In some instances controlled substances may not be the best treatment, the amount prescribed may seem excessive, or the patient may have become addicted as a result of treatment.

For example, a frequently seen patient who complains of back pain may be using opioids to relieve that pain. There are medical alternatives, some invasive and some conservative, to the use of opioids, but the patient refuses these alternatives in favor of treatment with opioids. The patient may develop dependence to these drugs but sees the dependence as the price that must be paid to avoid the alternative treatments that do not appeal to the patient. Controlled substances are not strictly necessary for this patient because alternative treatments are available. However, the patient really does suffer pain, and controlled substances are rationally related to the control of pain. Thus, although it might not be the best medical treatment, the prescribing of controlled substances for this patient is certainly both legitimate and medical. It does not matter that some physicians may treat the patient without prescribing opioids.

If the patient in this hypothetical case receives other controlled substances not just for pain but also for anxiety and insomnia, the prescribed dosages of each drug may be extremely high. Some may say that the prescriptions then become nonlegitimate. This position is not consistent with the federal framework, however. Under federal interpretations of the legitimate medical purpose rule, the objective is to prevent the diversion of medications to the illicit market without impeding the legitimate use of medications. The DEA is a law enforcement agency that does not have the expertise to make medical judgments, and there is nothing to suggest that anyone other than the patient is using the prescribed drugs or that the drugs are being used for anything other than conditions requiring the medical treatment for which they are indicated. Even though the dosages may be high and the combination risky, the use is legitimate because patients differ in their need for drugs and in their attitudes toward risk.

This is not to say that the pharmacist should not question the prescriber’s choice of drug therapy when professional judgment warrants. For example, if one drug has been shown more effective than another for a particular type of pain, or the dosage selected raises significant safety or efficacy issues, the pharmacist should intervene as appropriate. Perhaps the pharmacist, in an extreme case, may make a decision not to dispense the medication. Decisions to intervene and/or not dispense, however, should be based upon patient safety, weighing all clinical factors. The decisions should not be based upon the legitimate medical purpose rule.

In response to comments and solicitations from professionals and professional organizations in the pain management sector, the DEA published a notice in September 2006 titled, “Policy Statement: Dispensing Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain” (70 Fed. Reg. 52716, Sept. 6, 2006; http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov:80/fed_regs/notices/2006/fr09062.htm). Although directed primarily at prescribers, the notice might help pharmacists better understand the position of the DEA on this subject.

Differentiating Treatment of Addiction from Treatment of Pain

Federal regulations specifically state that it is illegal to prescribe and dispense narcotic drugs for the purpose of maintaining an addiction or detoxifying an addict (21 C.F.R. § 1306.04(c)). The intent of the regulation is to ensure that addicts are treated for their addiction in registered opioid treatment programs. DATA does allow office-based practitioners to prescribe schedule III, IV, and V opioid drugs specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the purpose of treating addicts. Thus, it may be simply stated that, absent legal exceptions (most notably DATA), it is not a legitimate use or a legitimate medical purpose of a controlled substance prescription to maintain an addiction or detoxify an addict.

The application of this principle in pharmacy practice is not often simple. For example, assume that the patient with back pain has taken the medication for several months and the pharmacist has reason to believe that the patient really does not have pain any longer. The pharmacist suspects that the patient is addicted to the drug and that is the only reason the patient is taking the drug. In this situation, the pharmacist should try to determine if the medical condition for which the drug was prescribed still exists or if the drug is being issued for the illegal purpose of maintaining a narcotic addiction. At this point, the pharmacist has a duty to contact the prescriber and inquire. If the prescriber can substantiate that the patient still has the back pain and the use of the drug is still necessary for this purpose, the pharmacist should continue to dispense the drug. The regulations support this action because they state that a physician may administer or dispense narcotic drugs to persons with intractable pain in which no relief or cure is possible or has been found after reasonable efforts (21 C.F.R. § 1306.07(c)). On the other hand, the prescriber might share the pharmacist’s concern that the purpose of the prescription is really the addiction and not the pain. In this situation, the prescriber might seek to enter the patient into an opioid treatment program or, if qualified, treat the patient under the requirements of DATA.

Situations get even more complicated when a pharmacist receives an opioid prescription with directions to gradually taper down the dosage. This complex situation requires the pharmacist to differentiate addiction from dependence. Addiction is generally characterized as psychological dependence characterized by compulsive use of the drug despite harm, a loss of control, and a preoccupation with obtaining opioids. Physical dependence is a state of adaptation in which withdrawal occurs when the drug is stopped or quickly decreased. Physical dependence is normal and expected with long-term opioid use. Thus, if the purpose of the opioid prescription is to gradually withdraw the pain patient from dependence, the prescription is legitimate. If the purpose is detoxification of an addict, the prescription is not legitimate. If the patient has been a regular pain patient of the pharmacy, the pharmacist can likely presume the taper-down dosage is withdrawal from dependence. If, however, the patient is new or a stranger, the pharmacist would likely need to query the prescriber and learn more.

There are exceptions under federal law, other than DATA, that allow for the limited treatment of addicts outside of opioid treatment programs (OTPs). Under CSA regulations (21 C.F.R. § 1306.07(b)), it is permissible for the prescriber to administer from his or her office supply, but not prescribe, narcotic drugs to an addict for a maximum of three days for the purpose of relieving acute withdrawal symptoms while arrangements are being made for referral for treatment. Not more than one day’s medication may be administered to the person at one time. (Note that the pharmacist may not dispense the medication pursuant to a prescription, as discussed under “Treatment of Addicts Outside of OTPs (DATA).”) The regulations also permit a physician or authorized hospital staff member to administer or dispense narcotic drugs to maintain or detoxify a hospitalized patient incidental to treating a condition other than the addiction (21 C.F.R. § 1306.07(c)).

Ascertaining the Legitimacy of Opioid Prescriptions in Pain Treatment

One of the most difficult situations pharmacists encounter is when a prescriber or prescribers issue several prescriptions to chronic pain patients for very large quantities and very large doses of opioids. Large quantities and doses are sometimes necessary to treat severe chronic pain patients. Because pharmacists are held to a corresponding responsibility with the prescriber, these situations can be uncomfortable if the pharmacist fears the patient might not be a legitimate pain patient. General DEA tips on determining the validity of prescriptions were mentioned previously and should be considered. More specifically to pain treatment, pharmacists should be aware of the standards of practice for diagnosing and treating pain. One good source for pain policies and online education on this matter is the Federation of State Medical Boards (available at http://www.fsmb.org/policy-and-education/education-meetings/pain-policies). If a pharmacist is concerned about the legitimacy of a pain patient, the pharmacist should not hesitate to contact the prescriber and ascertain if he or she is complying with practice standards. Pain management physicians should have no problem sharing medical records with the pharmacy, or developing a collaborative practice arrangement with the pharmacy.

Absent medical record documentation or a collaborative practice situation when uncertainty exists, pharmacists should consider interviewing the patient when appropriate with such questions as: What causes the pain? What past treatments has the patient attempted for the pain? What is the nature and intensity of the pain? What is the duration of the pain? What effect is the pain having on the patient’s quality of life? The pharmacist should then ask the same questions of the prescriber and should receive the same answers from both the prescriber and the patient. If available, pharmacists should also utilize the state’s prescription monitoring program to evaluate a chronic pain patient’s behavior.

DISPENSING OF SCHEDULE II CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

Subject to special exceptions, a pharmacist may dispense schedule II drugs only pursuant to a written prescription, signed by the individual practitioner (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(a)). Electronic prescriptions for schedule II drugs also are permitted, as discussed under “Electronic Transmission Prescriptions,” provided all DEA requirements are met. Schedule II prescriptions may not be refilled (21 C.F.R. § 1306.12). Pharmacists must reconcile federal with state requirements, as many states have additional or stricter requirements regarding schedule II prescriptions. For example, although federal law does not have a limit on the quantity ordered or a time frame for filling schedule II prescriptions, many states have specific rules addressing these matters.

State Multiple-Copy and Security Prescription Form Programs

In the past, some states required prescribers to issue schedule II prescriptions on multiple-copy, state-issued prescription forms. Typically, only the prescriber could request and possess these forms. When the prescriber executed a multiple-copy prescription form, generally the prescriber kept one copy, the dispensing pharmacy kept one copy, and the pharmacy sent another copy to a state office. In Whalen v. Roe, 429 U.S. 589 (1977), reported in the case studies section of this chapter, New York’s multiple-copy law was challenged as unconstitutionally violating the patient’s right of privacy. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law, however, finding that the law might have the intended effect of minimizing drug misuse and deterring potential violators without substantially interfering with any privacy rights.

Electronic data transmission programs (known as prescription monitoring programs (PMPs)) have generally replaced state multiple-copy prescription programs and have been implemented in most states. State PMPs generally require the electronic reporting of all controlled substance prescription information, not just schedule II prescriptions; this topic is discussed under “State Electronic Prescription Monitoring Programs (PMPs).”

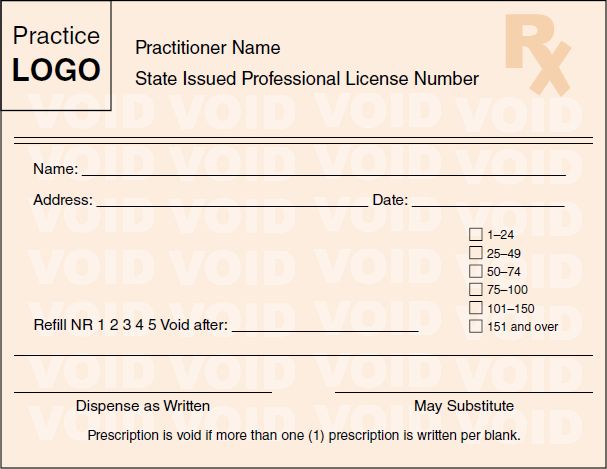

A more current effort by many states to help address fraudulent written prescriptions includes the requirement for prescribers to use security or tamper-resistant prescription pads. Typically, in order for written prescriptions for controlled substances to be filled at pharmacies in the state, the prescriptions must be written by prescribers on state-approved prescription pads only available from state-approved vendors. Approved prescription pads typically include numerous security features to prevent unauthorized copying or fraud, including watermarks and quantity check-off boxes. A template/example used by numerous states is provided here (see Figure 5-1). Federal requirements regarding tamper-resistant prescription pads are discussed under “Tamper Resistant Prescription Pads.”

Emergency Situations

Emergency situations constitute an exception to the requirement that a pharmacist may dispense schedule II drugs only pursuant to a written (or electronic) prescription. In an emergency situation, a pharmacist may dispense a schedule II drug on the oral authorization of an individual practitioner, provided that

FIGURE 5-1 Sample security/tamper-resistant prescription pad.

Courtesy of State of Indiana Professional Licensing Agency.

• The quantity prescribed and dispensed is limited only to the amount necessary to treat the patient for the emergency period. (Note: Some state regulations are stricter and provide for a numerical quantity or day supply limit that can be prescribed.)

• The prescription must be immediately reduced to writing by the pharmacist and shall contain all required information, except the signature of the prescriber.

• If the prescriber is not known to the pharmacist, the pharmacist must make a reasonable, good-faith effort to determine that the oral authorization came from a registered individual practitioner. This reasonable effort could include a callback to the prescriber using the phone number in the telephone directory, rather than the number given by the prescriber over the phone.

• Within seven days after authorizing an emergency oral prescription, the prescriber must deliver to the dispensing pharmacist a written prescription for the emergency quantity prescribed. (Note: The requirement was 72 hours before March 28, 1997.) The prescription must have written on its face “Authorization for Emergency Dispensing,” and the date of the oral order. The written prescription may be delivered to the pharmacist in person or by mail. If delivered by mail, it must be postmarked within the seven-day period. On receipt, the dispensing pharmacist shall attach this prescription to the oral emergency prescription previously reduced to writing. If the prescriber fails to deliver the written prescription within the seven-day period, the pharmacist must notify the nearest office of the DEA. Failure of the pharmacist to do so will void the prescription (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(d)). (Note: Although the regulation specifies “oral authorization,” the DEA has indicated in the Pharmacist’s Manual that a faxed prescription from the prescriber also would be acceptable.)

An emergency situation is defined as a situation in which

• Immediate administration of the controlled substance is necessary for the proper treatment of the patient.

• No appropriate alternative treatment is available.

• It is not reasonably possible for the prescribing physician to provide a written prescription to the pharmacist before dispensing. (21 C.F.R. § 290.10)

Facsimile (Fax) Prescriptions for Schedule II Drugs

DEA regulations permit the limited use of faxed prescriptions as another exception to the requirement that pharmacists may only dispense schedule II drugs pursuant to the actual written prescription from the prescriber. In general, faxed schedule II prescriptions are permitted but only if the pharmacist receives the original written, signed prescription before the actual dispensing and the pharmacy files the original (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(a)). (In essence, this general provision does not provide an exception for pharmacists because the original prescription is still required.) In three situations, however, the faxed prescription may serve as the original:

1. If the prescription is faxed by the practitioner or practitioner’s agent to a pharmacy and is for a narcotic schedule II substance to be compounded for the direct administration to a patient by parenteral, intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intraspinal infusion (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(e)).

2. If the prescription faxed by the practitioner or practitioner’s agent is for a schedule II substance for a resident of a long-term care facility (LTCF) (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(f)).

3. If the prescription faxed by the practitioner or practitioner’s agent is for a schedule II narcotic substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified by/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII, or licensed by the state. The practitioner or agent must note on the prescription that the patient is a hospice patient (21 C.F.R. § 1306.11(g)).

Note that for LTCF residents the prescription may be for any schedule II drug, in contrast to prescriptions for home healthcare and hospice patients. Pharmacists may dispense faxed prescriptions for hospice patients regardless of whether the patient lives at home or in an institution. Allowing faxed schedule II prescriptions for home healthcare, LTCF, and hospice patients has somewhat eased the burden of pharmacists, who often find it impractical to obtain the original written prescription for patients in these situations.

Partial Filling of a Schedule II Prescription

If a pharmacist is “unable to supply” the full prescribed quantity of a schedule II drug, partial filling of the prescription is permissible (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(a)). The pharmacist must make a notation of the quantity supplied on the face of the prescription, and the balance of the prescription amount must be filled within 72 hours after the partial filling. If the pharmacist is unable to fill the prescription within this time frame, the pharmacist must notify the prescriber. No further quantity may be supplied beyond 72 hours without a new prescription.

Historically, pharmacists have interpreted the phrase “unable to supply” as meaning that partial filling is permissible only if the pharmacy is out of stock. This interpretation places the pharmacist in a dilemma when the pharmacist receives a prescription for a large quantity of an opioid in a situation where validation may be necessary but not possible at the time. The pharmacist, not absolutely certain if the prescription is legitimate, must either fill the entire amount (risking possible diversion) or not dispense the prescription (resulting in the suffering of a legitimate patient). When queried about this dilemma, the DEA’s chief of the liaison and policy section replied that in such situations the pharmacist could partially fill the prescription, even if the drug is in stock, while waiting for verification. The DEA official additionally stated that a pharmacist could partially fill a prescription if the prescription was for a large quantity and the patient could not afford to pay for the entire amount or did not want the entire amount for some other reason. The response was that these situations also would fit within the definition of “unable to supply” (Brushwood, 2001).

In LTCFs, or for a patient with a medical diagnosis documenting a terminal illness, schedule II prescriptions may be partially filled to allow for the dispensing of individual dosage units but for no longer than 60 days from the date of issuance (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(b)). The total quantity of drug dispensed in all partial fillings must not exceed the quantity prescribed. If there is any question regarding whether a patient may be classified as having a terminal illness, the pharmacist must contact the prescriber before partially filling the prescription. Both the pharmacist and the prescriber have a corresponding responsibility to ensure that the controlled substance is for a terminally ill patient. The pharmacist must record on the prescription whether the patient is “terminally ill” or an “LTCF patient.” A prescription that is partially filled and does not contain the notation “terminally ill” or “LTCF patient” is deemed to have been filled in violation of the CSA.

For each partial filling, the pharmacist must record

• The date

• The quantity dispensed

• The remaining quantity authorized to be dispensed

• The identification of the dispensing pharmacist

This record may be kept on the back of the prescription or on any other appropriate record, including a computerized system. If a computerized system is used, it must have the capability to permit the following:

• Output of the original prescription number; date of issue; identification of the prescribing individual practitioner, the patient, the LTCF, and the medication authorized, including the dosage form strength and quantity; and a listing of partial fillings that have been dispensed under each prescription

• Immediate (real-time) updating of the prescription record each time that the prescription is partially filled (21 C.F.R. § 1306.13(c))

Multiple Schedule II Prescriptions for the Same Drug and Patient Written on the Same Day

The fact that the law prohibits the pre- or postdating of controlled substance prescriptions and the refilling of schedule II prescriptions can create hardships for patients who regularly require the dispensing of drugs in this schedule. Recognizing this, the DEA for years has permitted physicians to prepare multiple prescriptions on the same day for the same schedule II drug with written instructions that they be filled on different days. In 2003, the DEA issued a private letter to a physician confirming that this practice is permissible (letter from Patricia Good, DEA, to Howard Heit, physician, January 31, 2003). Subsequently, the DEA posted confirmation of the policy on its website, as well as on a pain management website. Then, without warning, the DEA reversed its position and issued a Federal Register notice to this effect in 2004 (69 Fed. Reg. 67170), causing an uproar among pain management and healthcare professional organizations. Nonetheless, the DEA reiterated its new position in another Federal Register notice in August 2005 (70 Fed. Reg. 50408), stating that this practice amounts to illegal refills.

After repeated complaints from pain specialists, in September 2006 the DEA issued yet another reversal of opinion, proposing a new regulation on the subject (http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2006/fr0906.htm) as well as an accompanying policy statement, “Dispensing Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain” (71 Fed. Reg. 52724; 71 Fed. Reg. 52715; http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/notices/2006/fr09062.htm). The policy statement is an attempt by the agency to clarify the legal requirements and agency policy regarding the prescribing of controlled substances for the treatment of pain. The DEA issued the final rule in November 2007, permitting the issuance of multiple prescriptions subject to the following restrictions (72 Fed. Reg. 64921):

• Each prescription must be issued on a separate prescription blank.

• The total quantity prescribed cannot exceed a 90-day supply.

• The practitioner must determine there is a legitimate medical purpose for each prescription and be acting in the usual course of professional practice.

• The practitioner must write instructions on each prescription (other than the first) as to the earliest date on which the prescription may be dispensed.

• The practitioner concludes that the multiple prescriptions do not create an undue risk of diversion or abuse.

• The issuance of multiple prescriptions must be permissible under state law.

• The practitioner must comply fully with all other CSA and state law requirements.

DISPENSING OF SCHEDULE III, IV AND V CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

A pharmacist may dispense a schedule III, IV, or V prescription drug pursuant to either a written, faxed, electronic, or oral order from the individual practitioner or practitioner’s agent, providing that all required information is contained on the prescription, and that electronic prescriptions conform to DEA requirements. Oral orders must be promptly reduced to writing; written and faxed prescriptions must contain the signature of the prescriber (21 C.F.R. § 1306.21(a)). Individual practitioners may administer or dispense a schedule III, IV, or V controlled substance in the course of professional practice without a prescription (21 C.F.R. § 1306.21(b)). Institutional practitioners may administer or dispense (but not prescribe) a schedule III, IV, or V controlled substance pursuant to a written, faxed, or oral prescription promptly reduced to writing by the pharmacist, as well as administer or dispense an order for medication by an individual practitioner that is to be dispensed for immediate administration to the ultimate user (21 C.F.R. § 1306.21 (c)).

Refills

No schedule III or IV prescription may be filled or refilled more than six months after the date of issuance of the prescription or more than five times, whichever comes first (21 C.F.R. § 1306.22). These restrictions do not apply to schedule V prescription drugs. After the expiration of the six-month period or the fifth refill, the prescriber must authorize a new prescription. The pharmacist may telephone the prescriber for authorization and create a new prescription.

If the prescriber who issued the original prescription initially authorized fewer than five refills, that prescriber can authorize additional refills without having to issue a new prescription. In any event, the total quantity of refills authorized, including the number on the original prescription, cannot exceed five refills. A pharmacist who obtains oral authorization for additional refills must record the refill either in hard copy form or in an automated data system. The quantity of each additional refill authorized cannot exceed the quantity originally authorized on the prescription.

If an automated system is not used, every refill must be recorded either on the back of the prescription or on another document in a way that makes the information readily retrievable. The recorded information must be retrievable by prescription number and must include

• The name and dosage form of the drug

• The date refilled

• The quantity dispensed

• The initials of the dispensing pharmacist for each refill

• The initials of the pharmacist receiving the refill authorization

• The total number of refills for that prescription

If the pharmacist merely initials and dates the back of the prescription, it is deemed that the full face amount of the prescription was dispensed.

It is not advisable that pharmacists refill controlled substance prescriptions when the prescriber is not available for authorization on the expectation that the prescriber will subsequently approve the refill. This practice is illegal, unless authorized by state law, and even in states that so authorize, refills are generally confined to emergency situations where the patient’s health would be jeopardized if the prescription was not refilled. In the case of Daniel Family Pharmacy, 64 Fed. Reg. 5314 (February 3, 1999), reported in the case studies section of this chapter, a pharmacist refilled a narcotic drug prescription for an employee believing the refill would be approved by the prescriber. The prescriber, however, refused authorization, leading the pharmacist down a path of escalating illegal activities.

Electronic Refill Records

As an alternative to the method of recording refill information previously discussed, a pharmacy may use an electronic system for the storage and retrieval of refill information for schedule III and IV prescriptions (21 C.F.R. § 1306.22(f)). Such a system must provide online retrieval of the original prescription order information and the up-to-date refill history of the prescription. The pharmacist must verify and document that the refill data entered into the system are correct.

If the system provides a hard copy printout of each day’s refill data, that printout must be provided to the pharmacy within 72 hours of the date on which the refill was dispensed. The printout must be verified, dated, and signed by each pharmacist who refilled the prescriptions listed on the printout. This document must be maintained in a separate file at the pharmacy for a period of two years from the dispensing date. In lieu of the printout, the pharmacy may maintain a bound logbook or separate file for refills in which each individual pharmacist involved in dispensing medications signs a statement verifying the prescriptions that the pharmacist refilled. The logbook also must be maintained for a period of two years.

All computerized systems must be able to print out any refill data that the pharmacy is responsible for maintaining. This includes, for example, a refill-by-refill audit trail of any schedule III or IV prescription. The printout must include

• The name of the prescriber

• The name and address of the patient

• The quantity dispensed on each refill

• The date of dispensing for each refill

• The name or identification code of the dispensing pharmacist

• The number of the original prescription order

If records are kept at a central location, the printout must be capable of being sent to the pharmacy within 48 hours.

Pharmacies with an automated system must have an auxiliary system for documenting refills in the event that the computerized system suffers downtime. The auxiliary system must maintain the same information as the automated system. A pharmacy must use either a manual or electronic system, but not both, to store and retrieve refill information.

Partial Filling of Schedule III, IV, or V Prescriptions

It is permissible for pharmacists to partially fill a prescription for a schedule III, IV, or V drug provided that

• The partial filling is recorded in the same manner as a refill.

• The total quantity dispensed in all partial fillings does not exceed the total quantity prescribed.

• No dispensing occurs six months after the date of issuance.

Pharmacy providers should not confuse a refill with a partial fill, and ensure that patients have access to their medication when appropriate. For example, consider a prescriber that orders a patient a schedule IV medication, #30 lorazepam 1-mg tablets with 5 refills, and instructs the patient to take one tablet daily as needed. The patient could obtain a total of 180 pills in six months from the issuance date of the prescription, if he or she obtained the medication each month (30 initial pills the first month, then 30 additional pills each month for the next five months). However, if the patient desires to obtain only 15 tablets at one time, the patient could return for an additional 11 partial fills of 15 tablets (the total quantity dispensed in all partial fillings (180) does not exceed the total quantity prescribed (180)). Oftentimes, pharmacy computer programs identify a partial fill as a refill and warn the pharmacist after five partial fills that the prescription has no valid refills, when actually the patient is still permitted to receive the medication.

Labeling of Schedule II, III, IV, and V Prescriptions

A pharmacist dispensing a controlled substance must affix to the container a label that shows the date of filling if it is a schedule II drug (21 C.F.R. § 1306.14(a)). The label must show the date of the initial filling if it is for a schedule III, IV, or V drug (21 C.F.R. § 1306.24(a)). The date of initial filling should be used when dispensing refills of schedule III or IV prescriptions. Technically, because the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act specifies that the label must contain the date of filling, both dates should be on the label of a refill to comply with both laws. In addition, the regulation requires the label to include

• Pharmacy name and address

• Serial number of the prescription

• Name of the patient

• Name of the prescriber

• Directions for use and cautionary statements, if any

For schedule II, III, and IV drugs, the label should also include a cautionary statement with the following language: “Caution: Federal law prohibits the transfer of this drug to any person other than the person for whom it was prescribed” (21 C.F.R. § 290.5).

These labeling requirements do not apply if the drug is prescribed for administration to an institutionalized ultimate user (medication order) (21 C.F.R. § 1306.14(c) and 21 C.F.R. § 1306.24(c)) provided that

• If the drug is in schedule II, no more than a seven-day supply is dispensed at one time. If the drug is in schedule III, IV, or V, no more than a 34-day supply or 100 dosage units, whichever is less, is dispensed at one time.

• The drug is not in the possession of the ultimate user before the administration.

• The institution maintains appropriate safeguards and records regarding the proper administration, control, dispensing, and storage of the drug.

• The system used by the pharmacist in filling the prescription is adequate to identify the supplier, the product, and the patient, and to state the directions for use and cautionary statements.

ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION PRESCRIPTIONS

After years of waiting and anticipation by practitioners, in 2010 the DEA authorized the electronic transmission of controlled substance prescriptions. (Proposed regulations were issued in June 2008 (73 Fed. Reg. 36721) and interim final regulations (IFR) on March 31, 2010 (75 Fed. Reg. 16236).) The IFR permits the e-prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances in schedules II–V.

The DEA structured the regulations to accomplish two purposes: (1) security, such that only authorized persons have access to the electronic system, and that only the authorized persons are actually using the system; and (2) accountability, such that a prescription cannot be repudiated and that violators of the law can be readily identified.

Prescriber Requirements

To ensure that only authorized persons have access to an e-prescribing system, the regulations require that prescribers must undergo identity proofing, either in person or remotely, with a federally authorized entity. Once identity is proven, the prescriber is provided an authentication credential or a digital certificate.

To sign and transmit e-prescriptions, the prescriber must use a two-factor authentication method. The prescriber must choose two of three factors for this purpose, which act as a digital signature. These factors include: (1) something you know, such as a password or PIN number; (2) something you have, a hard token separate from the computer such as a personal digital assistant, cell phone, or flash drive; or (3) something you are (biometrics).

An agent of the prescriber may enter the appropriate prescription information into the system for later approval and authentication by the prescriber. However, an agent cannot have access to the two-factor authentication to sign the prescriptions. The prescription ultimately transmitted to the pharmacy must contain all of the information required on paper prescriptions.

Pharmacy Requirements

When the electronic prescription is transmitted to the pharmacy, the first recipient of the e-prescription (either the pharmacy or its application service provider if it uses one) must digitally sign, and the pharmacy must archive the e-prescription. If a prescription transmission fails, the prescriber may write a copy of the transmitted prescription and sign it. The copy must indicate that it was originally transmitted to a specific pharmacy and that the transmission failed. The pharmacy must check to ensure that the e-prescription was not received or dispensed before it dispenses the paper prescription. Similarly, if a pharmacist receives a paper or oral prescription indicating that it was originally transmitted electronically to another pharmacy, the pharmacist must check with that pharmacy to determine whether the e-prescription was received. If it was received but not dispensed, the pharmacy that received it must void it. If the original e-prescription was dispensed, the pharmacy with the paper prescription must void it.

A pharmacy may make changes to the electronic prescription after receipt in the same manner that it may make changes to paper controlled substance prescriptions. The pharmacy must maintain a daily internal audit trail that compiles a list of auditable events (those that indicate a potential security problem). Pharmacies must back up all electronic prescription records daily and they must be kept for two years. Electronic prescriptions may be electronically transferred between pharmacies subject to the same requirements as if the transfer was by paper or oral. More information on the e-prescription requirements is available at http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/ecomm/e_rx/index.html#faq.

Audit or Certification Requirements

The DEA has strongly emphasized that both the prescriber’s and the pharmacy’s application systems must either be approved by a third-party audit conducted by a qualified person or verified and certified by a certifying organization whose process has been approved by the DEA (76 Fed. Reg. 64813, available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-10-19/pdf/2011-26738.pdf). All certifying organizations with an approved certification process are posted on the DEA’s website: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov, under electronic prescriptions. E-prescriptions may not be transmitted, received, or dispensed unless the application systems meet all DEA requirements. Thus, if doubts exist, the pharmacy should request proof from the prescriber that its system has been properly audited or certified.

TRANSFERRING OF PRESCRIPTION INFORMATION

Pharmacies may transfer information between themselves for refill purposes for schedule III, IV, and V prescriptions on a one-time basis only, if state law allows. Regulations enacted March 28, 1997, however, allow pharmacies that electronically share a realtime, online database to transfer back and forth up to the maximum refills permitted by law and the prescriber’s authorization. A transfer can take place only by means of direct communication between two licensed pharmacists (21 C.F.R. § 1306.25).

The transferring pharmacist must

• Write “void” on the face of the invalidated prescription

• Record on the back of the invalidated prescription the name, address, and DEA registration number of the pharmacy to which the prescription was transferred, as well as the name of the pharmacist receiving the information

• Record the date of the transfer and the name of the pharmacist transferring the information

The pharmacist receiving the information must

• Write “transfer” on the face of the transferred prescription

• Reduce to writing all information required on a schedule III, IV, or V prescription, including

° The date of issuance of the original prescription

° The original number of refills authorized

° The date of original dispensing

° The number of refills remaining and the date(s) and locations of previous refill(s)

° The transferring pharmacy’s name, address, and DEA number, and the prescription number

° The name of the transferor pharmacist

° The pharmacy’s name, address, DEA number, and prescription number from which the prescription was originally filled

Both the original and the transferred prescription must be kept for two years from the date of the last refill.

RETURN OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES TO PHARMACY FOR DISPOSAL

Until recently, the DEA did not permit the return of controlled substances by a non-registrant (e.g., patients, LTCFs) to a pharmacy for disposal. The basis for the DEA’s opinion was that the law did not expressly permit this practice.

The agency recognized that its strict position on returns to a pharmacy conflict with its primary concern of reducing diversion and abuse, as well as the concerns of many in society who want safe and responsible options for the disposal of controlled substances. To these ends, the agency issued an advance notice of rulemaking in January 2009, seeking comments from stakeholders regarding what should be included in a regulation that would allow ultimate users and LTCFs to dispose of controlled substances (74 Fed. Reg. 3480). Subsequently, the DEA held a series of national take-back programs from 2010 to 2014 through local law enforcement agencies to facilitate the disposal of prescription drugs.

It was Congress, however, that proposed a remedy to the problem by passing the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-273). This law permits an ultimate user (i.e., patient) who has lawfully obtained a controlled substance to deliver it to another person for disposal, if the person receiving the controlled substance is authorized to engage in disposal and the disposal takes place pursuant to regulations to be issued by the DEA. The law also directed the DEA to develop regulations authorizing LTCFs to dispose of controlled substances on behalf of their residents.

The final DEA regulations implementing the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act became effective October 9, 2014 (79 Fed. Reg. 53520; http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/rules/2014/2014-20926.pdf). The regulations expand options available to collect controlled substances from ultimate users, including: takeback events, mail-back programs, and collection receptacle locations. The new rules allow authorized manufacturers, distributors, reverse distributors, narcotic treatment programs, hospitals/clinics with on-site pharmacies, and retail pharmacies to collect pharmaceutical controlled substances from ultimate users by voluntarily administering mail-back programs and maintaining collection receptacles. In addition, the regulations allow authorized hospitals/clinics and retail pharmacies to voluntarily maintain collection receptacles at LTCFs.

Two new important DEA definitions regarding disposal include “collection” and “collector.” The DEA defines collection as

to receive a controlled substance for the purpose of destruction from an ultimate user, a person lawfully entitled to dispose of an ultimate user decedent’s property, or a long-term care facility on behalf of an ultimate user who resides or has resided at that facility. (21 C.F.R. § 1300.01(b))

The DEA defines collector as

a registered manufacturer, distributor, reverse distributor, narcotic treatment program, hospital/clinic with an on-site pharmacy, or retail pharmacy that is authorized to so receive a controlled substance for the purpose of destruction. (21 C.F.R. § 1300.01(b))

Thus, to become a collector, an eligible entity must register with the DEA. The voluntary registration as a collector requires compliance with additional DEA rules. At the time of this publication, various pharmacy organizations had expressed concerns over pharmacies voluntarily registering as a collector. American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Executive Vice President and chief executive officer, Thomas E. Menighan, commented “[w]hile APhA supports the expansion of public access to secure medication disposal options, we are concerned that issues with safety, liability and cost that may affect participation of pharmacists and pharmacies” (APhA Responds to Disposal of Controlled Substances Final Rule, Sept. 9, 2014, available at http://www.pharmacist.com/apha-responds-disposal-controlled-substances-final-rule). Therefore, how pharmacies respond to the new DEA rules allowing voluntary registration as a collector remains to be seen.

The DEA offers a variety of resources for healthcare providers and consumers regarding drug disposal at the DEA website (http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/). Similarly, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and FDA offer guidelines to consumers for disposing of medications at http://water.epa.gov/scitech/swguidance/ppcp/upload/ppcpflyer.pdf and http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm101653.htm.

CENTRAL FILLING OF PRESCRIPTIONS

A central fill pharmacy is one that fills prescriptions for retail pharmacies pursuant to a contractual agreement or common ownership. When a retail pharmacy receives a prescription and then sends it to a second pharmacy to prepare and deliver back to the first pharmacy for dispensing to the patient, the second pharmacy is engaging in a “central fill activity.” Retail pharmacy conceived of central fill pharmacies in the late 1990s as a means to assist in handling increased volumes of prescriptions. A central fill pharmacy provides pharmacists the opportunity to increase the efficiency of resources, frees pharmacists’ time for patient care activities, reduces dispensing errors, and reduces patient wait time. Most state boards of pharmacy have enthusiastically embraced central fill pharmacies, and many states have enacted laws to enable such operations.

The DEA, however, did not originally recognize central fill pharmacies, and thus the central filling of controlled substance prescriptions was not legal. In order to rectify this situation, the DEA proposed regulations in 2001 (66 Fed. Reg. 46567, Sept. 6, 2001), to allow the central filling of controlled substances, and finalized the regulations on June 24, 2003 (68 Fed. Reg. 37405, 21 C.F.R. parts 1300, 1304, 1305, and 1306). Pursuant to the final regulations, central fill pharmacies may be registered as pharmacies, as long as state law authorizes this activity. Any person wishing to register as a central fill pharmacy and dispense controlled substances must do so in the same manner as any pharmacy. A central fill pharmacy must be staffed by a licensed pharmacist and may fill both new and refill prescriptions. Any prescription dispensed by the central fill pharmacy must be transported to the retail pharmacy that initially received the prescription, which would then deliver it to the patient. The label of the dispensed drug must contain a unique identifier (i.e., the central fill pharmacy’s DEA registration number), indicating that the prescription was filled at the central fill pharmacy (21 C.F.R. § 1306.24(b)). A central fill pharmacy cannot accept a prescription directly from a patient or individual practitioner or deliver a prescription directly to the patient or individual practitioner. Both the pharmacist at the central fill pharmacy and the pharmacist who ultimately dispenses the prescription to the patient are bound by the corresponding responsibility doctrine (21 C.F.R. § 1306.05(f)).

A central fill pharmacy must have a contractual arrangement with the retail pharmacies for which it provides services, keep a list of those pharmacies, and verify the DEA registration of those pharmacies (21 C.F.R. § 1304.05). A retail pharmacy similarly must keep a list of the central fill pharmacies with which it contracts and verify their DEA registration. The information at both pharmacies must be available to the DEA upon request.

A retail pharmacy may contract with a central fill pharmacy in another state providing that both states allow this activity. A retail pharmacy may, as a coincidental activity, operate also as a central fill pharmacy without maintaining a separate registration, inventories, or records.

The retail pharmacy must write the words “CENTRAL FILL” on the original paper prescription (21 C.F.R. § 1306.15 and § 1306.27). The retail pharmacy may then transmit the prescription to the central fill pharmacy in two ways. First, the controlled substance prescription (including schedule II prescriptions) may be faxed. The retail pharmacy must maintain the original hard copy, and the central fill pharmacy must maintain the faxed prescription. Second, the prescription information may be transmitted electronically. The DEA has determined that there appears little risk of diversion in this situation and thus does not require specific security standards for transmission. Of course, both pharmacies must keep all records related to the prescriptions transmitted and comply with all federal and state patient confidentiality and recordkeeping requirements.

INTERNET PHARMACY PRESCRIPTIONS

There are generally three types of Internet pharmacies. One type is operated by legitimate pharmacies that require a valid prescription from a community prescriber before they will dispense the medications. Generally, these are brick-and-mortar or mail-order pharmacies that have created websites where patients can request refills online and where prescribers can phone or fax new prescriptions for patients. These pharmacies are generally legal and the DEA is not concerned with this type of pharmacy.

The other two types of Internet pharmacies are often termed “rogue pharmacies.” Under the more blatant type of rogue Internet pharmacy, the patient transmits a request for particular prescription medications and the Web business mails the drugs to the patient without a prescription. In the second type of rogue operation, patients also transmit requests for particular prescription medications. However, the patients are required to complete an online survey asking some basic questions such as weight, sex, if they have high blood pressure, and the like. This survey is electronically routed to a physician who has contracted with the Internet operation and usually resides in a different state from the patient. The physician reviews the survey and issues a prescription to a contracting pharmacy. The pharmacy often is a community state-licensed pharmacy in a different state than the prescriber. The pharmacy then dispenses and mails the prescription medication to the patient, who generally lives in yet a different state.