Overview

The common feature of these conditions is uncertainty

The commonest uncertainty concerns possible causality

Uncertainty often extends to both susceptibility and treatment

Psychosomatic concepts are often relevant but are equally often rejected by those susceptible

Research is very difficult, arguable and quite often inconclusive

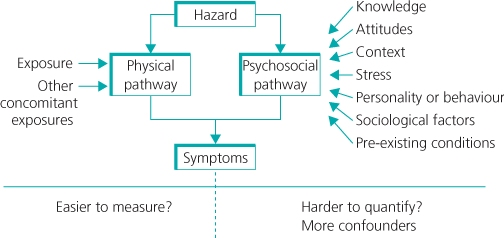

Occupational and environmental conditions, by their nature, invite and create contention. This is particularly so where causality is uncertain. Figure 14.1 seeks to explain why this might be. Individual and group beliefs, behaviours, and so on, and their social modulation seem to play as substantial a part in the experience of symptoms as does exposure to the range of putative causal agents.

The issues of causality, attitude and perception that affect approaches to these conditions are discussed first, before describing specific syndromes. From a practical point of view, there is an obvious dichotomy between the support it is proper to give to those affected and the more detached objectivity one would wish to bring to understanding their condition scientifically. This is particularly so when, as is often the case, health professionals are invited to make a commitment to a particular belief system related to the causality of the disorder under discussion. At the same time, those health professionals are all members of the public and as such are susceptible to prevalent, popular, belief systems.

Box 14.1 lists a selection of medical syndromes whose nature and aetiology are at present uncertain. They are an apparently disparate grouping, but as far as broader circumstances are concerned, they tend to reflect some common themes:

- multifactoriality (both symptoms and putative causes)

- lack of control (‘involuntary’ exposure)

- marked variation in susceptibility

- tendency to ascribe to external causes.

- Long-term conditions claimed to be associated with proximity to electromagnetic fields (for example, power lines) and nuclear installations

- Gulf war syndromes

- Multiple chemical sensitivity

- Situational syndromes: the Braer disaster and the Camelford incident

- Sick building syndromes

- Conditions claimed to be associated with proximity to landfill sites

- Long-term conditions claimed to be associated with pesticides used for sheep dipping

As such, there are resonances between these conditions and others considered elsewhere in this book or that are beyond its scope. These conditions include non-specific upper limb disorders, regional pain syndromes, fibromyalgia, stress and chronic fatigue syndrome.

To deconstruct the nature of the multifactoriality a little, in the cases of sick building syndromes, multiple chemical sensitivity and war syndromes, the factors implicated are truly extensive and highly varied, whereas in disaster/situational syndromes (for instance oil spills) they are defined by the event, although the nature of the elements of the exposure may still, to some extent, be arguable. The debates about electromagnetic fields and nuclear installations are even more unusual because they are biphasic with more or less distinct occupational and environmental modes.

Landfill and incinerator sites present another situational pattern. They are numerous, widely distributed and commonly complained of being the source of a range of effects (in time and space) and an even wider range of possible hazards and attendant risks. In contrast to all of the previous examples, the putative causal agents cited for conditions attributed to sheep dipping are highly specific—namely, organophosphate pesticides. Acute effects are well known and well characterized, but the controversy about how they might be implicated in longer term effects, continues.

Electromagnetic Fields and Nuclear Installations

Studies relating to power lines have been pursued for about 40 years and for nuclear installations, about 30 years. Their conclusions, except at the peripheries, are no longer as hotly debated as they were 10 or 20 years ago. Having come to some level of maturation as controversies, they may be taken as ‘worked examples’ of the assimilation of controversy into common or at least common scientific consensus as explained in the Box 14.2.

This consensus, as the relevant WHO monograph (No 238) explains is a ‘conceptual framework’ where the evidence ‘is not strong enough to be considered causal, but sufficiently strong to remain a concern.’

The scientific characteristics of that evidence are educative. They consist of a series of epidemiological studies published since about 1979 which have sparse data and low power. Odds ratios have been in the range 1–1.5 with wide confidence intervals often including unity. Taken together they show some consistency but the doubts noted in the Box 14.2 and other scientific cautionary factors, which include difficulties in precise measurement of exposure and lack of accountability for sources of bias and confounding, have to be recognized.

Numbers are sparse and exposure criteria poorly defined Studies on those occupationally exposed are even weaker. The difficulty in differentiating the ‘effect from background noise’ is typical of these sorts of long running debates. The rationale for continuing is nevertheless powerful because of the universality of exposure, the likelihood that exposure will increase in the future, the precautionary principle (see Chapter 22) and for reasons of risk perception.

With regard to nuclear installations, concerns have also centred around childhood leukaemia and other childhood cancers (Box 14.3). In the United Kingdom the debate was initiated by a single television programme in 1983. The putative risk factor at that time was assumed to be installation discharges of radioactive materials. However, such discharges produce doses to the general public that are very small (by several orders of magnitude) when compared with those that might be expected to produce such effects according to robust scientific risk estimations.

More generally, the risks of ionizing radiation, mainly cancer, have been studied intensively for 60 years. The pivotal cohort, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors (the Life Span Study (LSS)) to which other cohorts are always compared, is now coming to maturation with respect to definitive cancer outcomes. Such outcomes are expressed as a stochastic (statistical) excess of risk attributable to exposure.

From time to time the universal applicability of these stochastic norms are challenged in such a way as to call into question these risk predictions. This has happened recently (2005–2010) with respect to data nested in a very large international, occupational study where the so-called ‘all cancer risk’ from one participating country was at considerable odds (100–600%) to those of the others and LSS. Eventually this effect was traced to a basic ascertainment error associated with historical transfer of dosimetry data (and thus exposure) from one arrangement to another. However, it took 5 years to work this out. During that time, it permitted those who might have wished more systematically to disbelieve ‘conventional’ risk estimates to see the events described as grounds to support their views.

Such ‘challenge’ events are best regarded as a normal part of scientific activity. They are usually a consequence of statistically predictable variations in subsets of data that come to analysis but simple error occurs more frequently than one might expect. Real frameshifts in risk perception are much rarer and are usually less dramatic.

Even though the debate over scientific plausibility has subsided, these matters can still polarize scientific opinion at the extremes of construct belief.

Mobile Phones

The explosion in the global use of mobile phones applies to both occupational and public health fields in terms of hazard and risk. Their development has gone forward on the assumption that the well-understood, small, local, heating effects associated with radiofrequencies in mobile phone use are the sole risk and a negligible one.

This view has been challenged in two ways. First, by claims of association with mobile phone use of clusters of a range of illnesses, most prominently cancer. Second, that the universality of use, including by children and young people, demands both experimental reappraisal and epidemiological tracking on a large scale. As with power lines, this latter argument is persuasive as exposure is pretty universal, and so even a small adverse effect would have a significant population impact.

Recent ‘toxicological’, experimental studies have been unsuccessful in determining any new hazard. The largest cancer study to date, the Interphone Study, addressed head and neck cancers in mobile phone users in 13 countries. The official results were published in 2010 and reported ‘no overall risk’. Sub-analyses of the data, especially when adjustments were attempted for sources of possible bias, suggested both small adverse and protective effects and thus, unsurprisingly, the study has become the subject of controversy.

So far the evidence holds that any risk is small or non-existent. The Interphone Study, although large, suffered from the usual problems of case–control studies, which, in the end, means that they are better at raising issues than solving them. Only cohort studies on quite a large scale will give a more definitive answer and these could take decades to deliver.

Gulf War Syndromes

The Gulf war conflicts of 1990/91 and 2003 resulted in very low contemporaneous mortality and morbidity for the multinational forces engaged against Iraq. However, subsequent morbidity, usually described as Gulf war syndromes (Box 14.4), has been reported to be high, with quite marked variation between different countries of reporting levels, range of symptoms and persistence. For example, comparatively few French deployed alongside British and American troops developed the disorder. Unsurprisingly, this subject has generated a large amount of sometimes confusing literature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree