Chapter 20 Disorders of pigmentation

Disorders of hypopigmentation

Vitiligo

Clinical features

Vitiligo is a common acquired disease of unknown etiology characterized by loss of melanocytes resulting in macular areas of leukoderma that progressively enlarge and often become confluent.1–4 The incidence has been calculated as between 1% and 2% of the population.5,6 It affects all races but appears to be more common in people with dark skin. However, the latter may represent an overestimate, as the disease tends to be more noticeable in patients with darker skin. The sex incidence is equal, with a peak incidence between the ages of 10 and 30 years (up to 50% of cases). The disease is also seen in the very young and the elderly.7–10 In children, the mean age of onset is 6 years and there appears to be a slight predilection for females.9 Between 25% and 40% of patients have a positive family history of the disease; inheritance is non-mendelian, multifactorial, and polygenic.6,11,12 In patients with a positive family history the disease usually appears earlier in life.6 The frequency of the disease in siblings of affected patients is about 18 times that encountered in the general population.6 Vitiligo affects monozygotic twins concordantly in about 23% of cases.6

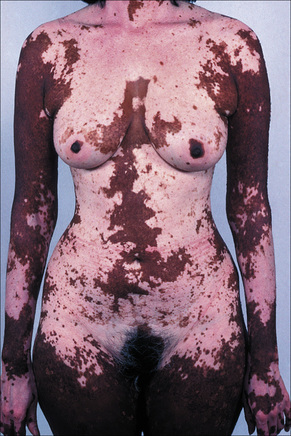

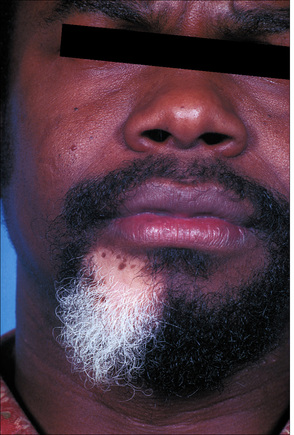

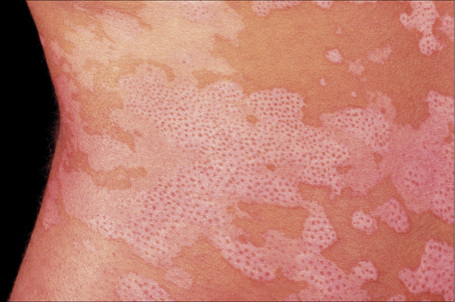

The progression of vitiligo is slow and it is common for lesions to start on sun-exposed skin and usually with a symmetrical distribution (Figs 20.1, 20.2).13,14 Stress has been suggested as a precipitating event in vitiligo in a number of patients.15 In a minority of cases involvement is unilateral. Segmental involvement with a dermatomal distribution is seen in some cases.16 Commonly, the skin over bony prominences is affected, suggesting that repeated trauma may play a role. Involvement of flexural areas, genitalia, and the skin around the eyes and mouth is also frequently seen (Fig. 20.3). Premature graying of the hair is a common event and occurs even in children. Affected areas are prone to sunburn and the Koebner phenomenon may be seen (Fig. 20.4). Early lesions can have an erythematous ’inflammatory’ border and in a minority of cases focal peripheral hyperpigmentation is a feature. Some patients describe mild pruritus in the early stages of the disease. The hairs within affected areas tend to remain pigmented but may lose the pigment in late stages (Fig. 20.5). A tanned zone between pigmented and completely nonpigmented skin is detected in some patients with darker skin. Known as trichrome vitiligo,17,18 it tends to indicate the presence of active disease.17 An unusual variant of inflammatory, figurate papulosquamous vitiligo has been documented.19 Vitiligo can also develop in individuals exposed to phenolic compounds, particularly in cleaning solutions.20 Patients may develop halo nevi (see Fig. 20.4) or vitiligo may develop after the development of halo nevi.21,22 Generalized complete depigmentation is exceptional. Spontaneous repigmentation may be seen but it is patchy and tends to concentrate in perifollicular skin (Fig. 20.6). A case of repigmentation of vitiligo after a beetle dermatitis has been documented.23 Patients with the disease occasionally have uveitis, and an association with deafness has also been reported.24,25

Fig. 20.1 Vitiligo: symmetrical involvement of the upper limbs.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 20.3 Vitiligo: genital involvement is often seen in vitiligo.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 20.5 Vitiligo: development of gray hair in a longstanding patch of vitiligo.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 20.6 Vitiligo: repigmentation in vitiligo frequently has a perifollicular distribution.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Some patients with vitiligo develop actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinomas on sun-exposed areas affected by the disease.26,27 This occurrence is, however, not as high as might be expected and may be due to inadequate sun protection. Patients treated with PUVA may be more prone to develop skin cancer in the involved skin.28

Polymorphic light eruption lesions limited to areas of skin involved by vitiligo has been described.29 Allergic contact dermatitis may exceptionally present as vitiligo.30

Vitiligo can be associated with numerous diseases, particularly (but not exclusively) those with a clear or suspected autoimmune basis. Autoimmune diseases may be seen in up to a third of patients with vitiligo. Patients with generalized vitiligo are more likely to have autoimmune disease The latter associations include thyroid disease (hypo- and hyperthyroidism and Hashimoto’s disease), diabetes mellitus, Addison’s disease, and (much less commonly) alopecia areata, acanthosis nigricans, dermatitis herpetiformis, pernicious anemia, spondyloarthritis, and pemphigus vulgaris (Fig. 20.7).31–41 The most frequent associations are with thyroid autoimmune disease, autoimmune gastritis, and alopecia areata.42 Patients with Grave’s disease or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis have a risk of more than 10-fold of developing vitiligo.43 Other reported associations of vitiligo include sarcoidosis, Crohn’s disease, morphea, lichen sclerosus, actinic granuloma, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, twenty-nail dystrophy, chronic actinic dermatitis, psoriasis, lepromatous leprosy, AIDS, MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes syndrome), frontoethmoidal meningoencephalocele, dysgammaglobulinemia, phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIa, and idiopathic CD4+ T-cell lymphocytopenia.39,44–60 Unilateral involvement in association with trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia has also been described.61 The vitiligo–spasticity syndrome seems to be a distinctive syndrome, mainly described in Arab patients but recently documented in a patient of North European extraction.62 Vitiligo may rarely occur at the site of radiotherapy.63,64 A single case of Baboon syndrome (systemic contact dermatitis as a result of inhalation of mercury vapor) with segmental vitiligo has been reported.65 Patients with melanoma rarely develop areas of leukoderma, not only around the tumor but also away from it and in association with metastasis.66–70 Poliosis may also occur. Of note, it has been suggested that the prognosis is better in patients with leukoderma and melanoma.68 It is controversial whether the depigmentation seen in patients with melanoma represents vitiligo.67

Fig. 20.7 Vitiligo: coexistence of vitiligo and alopecia areata.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Rarely, a number of drugs have been associated with vitiligo. These include chloroquine, ganciclovir, interferon-alpha (IFN-α), tolcapone, levodopa, PUVA, and imiquimod.68–79 Vitiligo has also occurred following narrow-band TL-01 phototherapy for psoriasis, at a site of allergic contact dermatitis to nickel, and after intense pulsed light treatment.80–82 The disease has also been induced by a lymphocyte infusion in a patient with relapsed leukemia and there is a report of an exceptional case of transfer of vitiligo after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.83,84

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of vitiligo remains obscure and there are a number of theories as to why the epidermal melanocytes are destroyed. It is likely that the disease is multifactorial, has an autoimmune basis and, in a number of cases, involves a genetic predisposition. Several of the mechanisms proposed are probably involved simultaneously.85,86 They are likely to be inter-related and often, genetic predisposition possibly plays a role. Susceptibility to generalized vitiligo and related autoimmune diseases is associated with variants of NALP1, which encodes NACHT leucine-rich repeat protein 1, a regulator of the innate immune system.87,88 It has been suggested that the gene encoding DDR1, which is the collagen IV receptor, is a susceptibility gene for vitiligo, perhaps by defective cell adhesion.89

Neurogenic hypothesis

One of the oldest hypotheses is termed the neurogenic hypothesis.90 This theory proposes the production of a neurochemical mediator by the nerve endings in the skin, leading to inhibition of melanogenesis and destruction of melanocytes. There is little experimental evidence to prove this but it has been suggested that neuropeptide Y may have a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.91 However, the neurogenic hypothesis does not have much weight and it is only mentioned for the sake of completeness.

Self-destruction theory

The second hypothesis is referred to as the self-destruction theory.92 This proposes that melanocytes are destroyed by toxic melanin precursors such as free radicals.93 It is not clear, however, why these toxic melanin precursors affect the melanocytes in some individuals and not in others but it may be that the mechanism for their disposal is faulty in patients who develop vitiligo. Experimental evidence is based on the fact that a number of chemicals induce pigmentary changes indistinguishable from vitiligo. It has also been demonstrated that death of melanocytes in vitiligo results from increased sensitivity to oxidative stress.94 The group of enzymes known as glutathione transferases is involved in protecting cells against toxic chemicals. Interestingly, it has been shown in a Chinese population that patients with GSTT1 and GSTM1-null genotypes have increased risk of developing vitiligo as compared to those that exhibit GSTP1 polymorphisms.95 It has been proposed that an alteration in the membrane lipids of vitiligo cells after stress leads to mitochondrial damage and production of reactive oxygen species.96 Thioredoxin domain containing 5 (TXNDC5) polymorphisms has been associated with the development of nonsegmental vitiligo in Korean patients.97 TXNDC5 is a member of the thioredoxin family and its function resides in protein folding and chaperone activity against endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by oxidative stress.

Autoimmune hypothesis

The third and favored theory is the autoimmune hypothesis which is based on the observation that patients with vitiligo have an associated autoimmune disease in up to between 15–30% of cases.15,31 Affected patients are also frequently found to have autoantibodies to gastric parietal, thyroid, and adrenal cells.98 Antibodies to normal melanocytes have been reported in patients with vitiligo.99–101 The level of these antibodies in the serum appears to correlate with disease activity.100,102 Important links have been shown between generalized vitiligo and single-nucleotide polymorphisms at several loci associated with autoimmune diseases.103 Interestingly, one of these associations is with a locus containing TYR which encodes tyrosinase. A mutually exclusive relationship between the tendency to develop vitiligo and susceptibility to melanoma has been suggested.103 Both antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity and direct destruction of melanocytes by antibodies have been proposed as mechanisms by which melanocytes are destroyed.102,104 Although it was initially suggested that the antibodies in the serum of patients are directed against tyrosinase, this view has been challenged.105–108 The activation of natural killer (NK) cells by antibodies does not seem to play an important role in some studies.109,110

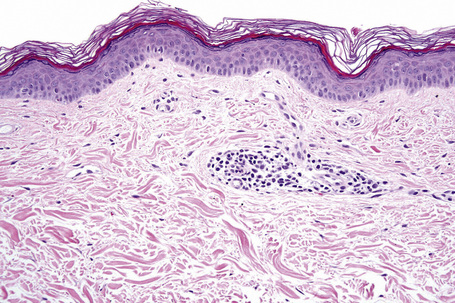

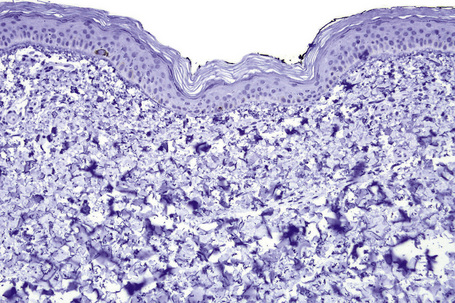

Histological features

Microscopic examination of involved skin in vitiligo shows complete absence of melanocytes in association with total loss of epidermal pigmentation (Fig. 20.8). Biopsies from the periphery of lesions with a clinically inflammatory border show lymphocytes and histiocytes in the papillary dermis. Some inflammatory cells may also be found at the periphery, even in the absence of a clinically inflamed border. A prominent mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate is exceptional.111 Degenerative changes have been documented in keratinocytes and melanocytes, not only from the border of lesions but also from adjacent skin.112,113 Degenerative changes in nerves and sweat glands have also been documented.114 Absence of Merkel cells in lesional skin was found in one study.115 Other reported changes include increased numbers of Langerhans cells, epidermal vacuolization, and thickening of the basal membrane.116 The loss of pigment and melanocytes in the epidermis is highlighted by a Masson-Fontana stain and by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 20.9). To avoid confusion with Langerhans cells (which are also S-100+) another melanocyte marker such as Melan-A may be used. Although both CD4- and CD8-positive cells are found within the infiltrate in active lesions, CD8-positive cells seem to predominate and appear to be associated with the damage at the dermoepidermal junction.117,118 This has been shown both in generalized and segmental vitiligo.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

Clinical features

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) (uveoencephalitis) disease is characterized by bilateral uveitis, poliosis, vitiligo, alopecia, dysacousia, and aseptic meningitis.1–5 It is more common in females (2:1), particularly from Latin America, Asia, Africa, and in Native Americans. It shows a predilection for adults, occurring only rarely in children. The initial phase of the disease usually starts with neurological symptoms and this is followed by ocular manifestations. In the acute phase, exudative retinal detachment is quite specific.6 As the disease progresses, patients develop cutaneous manifestations with focal or diffuse alopecia areata, vitiligo (mainly head and trunk), and poliosis (eyebrows, lashes, and hair) in the chronic stage of the disease. In the latter phase, sunset glow fundus is often found.6 It has been suggested that VKH disease is part of the spectrum of vitiligo with manifestations in other melanocyte-containing organs.1 Not every patient displays all the manifestations of the syndrome. Ocular complications consist mainly of glaucoma and cataracts.2,3 Rarely, the patches of depigmentation have an inflammatory edge.7,8 The disease is exceptionally preceded by erythroderma.9

VKH disease has been described in association with diabetes, hypothyroidism, melanoma, ulcerative colitis, Graves’ disease, psoriasis, and brainstem encephalitis.10–15 A possible association with combination therapy with IFN-α 2B/ribavirin has been documented.16

Pathogenesis and histological features

As with vitiligo, the pathogenesis of the disease remains unknown. An autoimmune basis is favored; however, it is likely that the etiology is multifactorial. This is based on the occurrence of the disease in identical twins and after cutaneous injury.17,18 An infectious etiology – particularly a virus – has been suggested in the past and this is supported by the recent simultaneous onset of the syndrome in a group of six patients living and working together.19 An association with HLA-DR53, HLA-DQ4,HLA-DR1, HLA-DR *0405 in Saudi Arabian patients, and HLA- DR4 in Brazilian patients suggests a genetic predisposition.20,21 A similar disease has been induced in rats by tyrosinase-related proteins TRP1 and TRP2, suggesting a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.22

The histopathology of the areas of cutaneous depigmentation is identical to that seen in vitiligo. In a single case report of a patient presenting with inflammatory vitiligo, filamentous masses and amyloid were described.8 The histological findings in areas of alopecia are identical to those seen in alopecia areata.23 However, more prominent release of melanin has been described, suggesting that the prime targets are the melanocytes within the hair follicle rather than the keratinocytes, as in classic alopecia areata.23

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis

Clinical features

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is a common asymptomatic dermatosis first described in 1951.1 It is characterized by a few to numerous white macules developing on sun-exposed skin, particularly the forearms and legs of middle-aged to elderly patients, with no sex predilection (Fig. 20.10). 2–4 Presentation in early life is exceptional and only rarely do lesions occur on the face and trunk.5,6 Most lesions are 5 mm or less in diameter. The condition affects all races and there is some suggestion of an increased familial incidence.7 Spontaneous repigmentation does not tend to occur. Lesions identical to those seen in this disease may also be a feature of Darier’s disease and develop following PUVA therapy.8,9

Pathogenesis and histological features

The exact pathogenesis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis remains unknown. It is likely that the cause of the disease is multifactorial. Factors that have been involved in its causation include inheritance, ultraviolet light, and loss of melanocytes due to aging in addition to autoimmunity.4–7,10–12 An association with HLA-DQ3 was found in a group of renal transplant patients with the disease while a similar group of renal transplant patients without the disease had HLA-DR8, suggesting that the latter may have a protective effect.13

The main histological feature consists of variable loss of melanin granules in epidermal keratinocytes. This is sometimes associated with epidermal atrophy and flattening of the rete ridges. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis in a basket-weave pattern has also been documented.7 A Masson-Fontana stain is useful to highlight the loss of epidermal melanin, and a dopa oxidase reaction reveals a patchy reduction in the number of melanocytes.2 However, complete loss of melanocytes is not a feature.

Electron microscopy studies confirm the reduction in the number of melanocytes. Changes described in melanocytes include cytoplasmic vacuolization and decrease or loss of mature melanosomes.5,6,11,14 Although the number of Langerhans cells is normal, a reduction in the number of Birbeck granules has been documented.10

Oculocutaneous albinism

The term ‘albinism’ is used to refer to a heterogeneous group of autosomal recessive conditions resulting from diverse genetic abnormalities that cause absent or reduced production of melanin pigment (Fig. 20.11).1,2 The genetic abnormality may result in eye involvement only (ocular albinism) or may combine involvement of the eyes, hair, and skin (oculocutaneous albinism). Here, only the different types of oculocutaneous albinism will be discussed.

At least 12 different gene mutations leading to different types of albinism have been identified.3 The clinical manifestations of oculocutaneous albinism depend on the type of biochemical abnormality. In all types of albinism, the lack of melanin in the developing eye results in hypoplasia of the fovea and abnormal routing of the optic nerves. As a result, all patients have variable strabismus, nystagmus, and reduced visual acuity.4 Affected patients often have an increased risk of skin cancer (Figs 20.12, 20.13). Based on clinical features alone, it is not always possible to separate the different types of oculocutaneous albinism.

Fig. 20.12 Oculocutaneous albinism: numerous actinic keratoses on sun-exposed skin.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Fig. 20.13 Oculocutaneous albinism: an early squamous cell carcinoma on sun-exposed skin.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

The most common types of albinism are oculocutaneous albinism types IA and II. Most types are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and affect all races.5,6 Prenatal diagnosis of oculocutaneous albinism is possible.7,8 Rare variants of albinism are associated with systemic manifestations and include the Hermansky-Pudlak and the Chédiak-Higashi syndromes (see below). The different types of oculocutaneous albinism and the histopathology of all variants are discussed briefly.

Oculocutaneous albinism type IA

Type IA oculocutaneous albinism is the most severe variant and is characterized by complete absence of tyrosinase activity in melanocytes. It is seen in all races but it is very rare in blacks. The prevalence is 1 in 40 000. At birth, patients have white hair, white or pink skin, and the eyes are blue or gray. Visual acuity is severely reduced. Patients usually do not have nevi or, if present, they are amelanotic and develop dark-brown freckles with sun exposure. Sun exposure leads to severe skin damage with an increased risk of skin cancer, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and (rarely) melanoma.9–13 A case of leukodystrophy and oculocutaneous albinism type IA has been documented.14

Pathogenesis

In all variants of albinism melanocytes and melanosomes are normal. The reduction or absence of melanin results from a biochemical abnormality in the synthesis of the pigment. The gene for tyrosinase has been cloned to chromosome 11q14.3. Numerous different mutations in the gene lead to absence of tyrosinase activity and the manifestations of the disease.4,15–18

Oculocutaneous albinism type IB

Oculocutaneous albinism type IB (yellow mutant) is uncommon and characterized by greatly reduced tyrosinase activity. It appears to be more common in Amish communities living in the United States.19 The hair of affected patients is white at birth and becomes yellow after a few months and light brown by the end of the second decade. The skin is milky white and becomes slightly tanned after sun exposure. The irises are gray. Visual acuity is better than in type IA disease and there is a lower incidence of skin cancer.

Type I variants

Other type I variants of oculocutaneous albinism include type I (temperature sensitive) and type I (minimal pigment). Each of these variants is thought to result from different mutant alleles at the tyrosinase locus.20

Type II oculocutaneous albinism

Type II oculocutaneous albinism (tyrosinase positive) is the most common type of oculocutaneous albinism. The color of the hair varies according to the race of the individual. All races have white skin but in black patients skin is brown and the irises are gray. The hair in Caucasian individuals is white or light yellow at birth and turns dark yellow during the first two decades of life.5 In individuals of African origin, the hair is yellow at birth and becomes dark yellow in the first two decades. Patients often develop nevi, lentigines, and freckles, which are particularly prominent on sun-exposed skin.

Pathogenesis

Oculocutaneous albinism type II is caused by mutations in the gene OCA2 (previously known as P-gene), which has been mapped to chromosome 15q11-q12.21–24 The OCA2 protein is important in the formation of melanosomes and in transport of melanosomal proteins TYR and TYRP1.24 It has been demonstrated that mutations in the melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) gene modify the classic phenotype seen in oculocutaneous albinism type II.25

Type III oculocutaneous albinism

Type III oculocutaneous albinism (rufous albinism) is also referred to as red oculocutaneous albinism. It is mainly seen in patients from Africa and New Guinea and exceptionally in patients from Pakistan.26 A single Caucasian patient has been reported.27 It results in red or ginger hair and red/brown skin.28,29 Visual anomalies are not always present.

Pathogenesis

Affected individuals are tyrosinase positive. The disease is caused by mutations in the tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TRP1) an important enzyme in melanin synthesis.30 The mutation results in delayed maturation and early degradation of tyrosinase. Electron microscopy examination reveals smaller melanosomes, aggregates of melanosomes within keratinocytes and increase in pheomelanin synthesis.31

Oculocutaneous albinism type IV

Oculocutaneous albinism type IV (brown) is a very rare variant of oculocutaneous albinism and is mainly seen in patients of African or Japanese origin.5,32 It is very rare in Europeans. Clinically, it is not possible to distinguish it from oculocutaneous albinism type II. Lentigines and freckles are rare. The hair is light brown and there is slight increase in pigmentation with age.

Pathogenesis

Oculocutaneous albinism type IV is caused by mutations in the membrane-associated transporter protein gene (MATP) in chromosome 5p13.3.33,34 The function of the protein is unknown but it probably acts as a membrane transporter in melanosomes.34

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome are described below.

Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome

Clinical features

Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is a very rare heterogeneous disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. It is characterized by partial tyrosinase positive oculocutaneous albinism, platelet storage deficiency with bleeding diathesis, and the accumulation of ceroid in the cytoplasm of macrophages.1–6 These macrophages are found in various organs including the skin and lung; pulmonary fibrosis is a frequent complication and leads to death.1,2 Additional manifestations include frequent infections, granulomatous colitis and (more rarely) renal involvement leading to renal failure.2–7 Other cutaneous features include trichomegaly, dysplastic nevi, actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinomas, and lesions resembling acanthosis nigricans.8 The phenotypic range of the disease is wide. The disease has mainly been described in Puerto Rico and people of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage and is exceptional in Europe.

Pathogenesis and histological features

There are eight variants of the disease involving the following genes: HPS1, AP3B1 (HPS2), HPS3, HPS4, HPS5, HPS6, DTNBP1 (HPS7), and BLOC1S3 (HPS8). Mutations in these genes give rise to the HPS subtypes 1 to 8, respectively.9–11 The syndrome is thought to be due to abnormal trafficking to lysosomes and related organelles, including melanosomes and platelet dense granules. It also affects T cells, neutrophils, and lung type II epithelial cells. Some variants of the disease are due to mutations in the adaptor-related code complex (AP-3) subunits.12 The role of the latter is to facilitate transport of vesicles from the Golgi apparatus and endosomal compartments. It has been demonstrated that the gene defects causing the disease in mice block melanosome biogenesis.13 The mechanisms of hypopigmentation demonstrated in mice consist of:

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome

Clinical features

Chédiak-Higashi syndrome is an uncommon autosomal recessive multisystem disorder characterized by partial oculocutaneous albinism, severe immunological dysfunction resulting in recurrent bacterial infections, a bleeding tendency, progressive neurological dysfunction, particularly peripheral neuropathy, and severe periodontitis.1–9 Characteristically, many cells (including melanocytes, myeloid cells, and lymphocytes) contain peroxidase-positive giant granules. The majority of patients die early in childhood as a result of either bacterial infection or an accelerated phase characterized by diffuse infiltration of organs (e.g. liver, spleen), lymph nodes, and bone marrow by lymphocytes and histiocytes.1,3 The accelerated phase is only rarely the first manifestation of the disease.10

Hemophagocytosis is common, as are hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia. About 10% of patients survive into adulthood but usually succumb to progressive neurological disease. Bone marrow transplant has a dramatic effect in preventing recurrent infections; it also prevents the accelerated phase of the disease but not the progressive neurological deterioration.11

The defect in pigmentation may affect skin, hair, and eyes. Affected individuals usually have light hair, and speckled hyper- and hypopigmentation of exposed areas may be seen.12

Pathogenesis and histological features

The tendency to develop recurrent infections is due to impaired chemotaxis and abnormal NK-cell function. Chédiak-Higashi syndrome and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (see above) are regarded as disorders of vesicle formation and trafficking.3,4,13–15 The gene for Chédiak-Higashi syndrome has been mapped to chromosome 1 and has been designated CHS1/LYST. The gene encodes a cytosolic protein of 430 kD. The exact function of this protein in vesicle trafficking is as yet unknown.3,4

A biopsy from involved skin shows marked reduction in the amount of melanin present in the epidermis and hair follicles. Giant melanosomes may be seen. These – and the giant granules found in other cells – are the result of giant lysosomes formed during fusion and phagocytosis.13,16

Giant melanosomes and smaller granules can be demonstrated in melanocytes by electron microscopy. Giant cytoplasmic granules have also been documented in Langerhans cells.17

Griscelli syndrome

Clinical features

Griscelli syndrome is a rare disease inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion and characterized by skin hypopigmentation, silver–gray hair, neurological abnormalities, and recurrent infections secondary to immunodeficiency (Fig. 20.14).1–3 Other features include hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, hypoproteinemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. Many of the manifestations of the disease are secondary to the presence of hemophagocytic syndrome, and these patients are classified as Griscelli syndrome type 1.1,4 Patients with neurological manifestations but no immunologic problems are classified as Griscelli syndrome type 2. The two phenotypes of the disease correlate with the type of genetic mutation (see below). A third type of the syndrome presents only with hypopigmentation: Griscelli syndrome type 3.5 Examination of hair shafts reveals prominent accumulation of melanin. An association with myelodysplastic syndrome has also been documented. Most clinical manifestations occur between the age of 4 months and 4 years. Unless bone marrow transplant is performed early in the course of the disease in patients with Griscelli syndrome type 1, death invariably occurs.6

Fig. 20.14 Griscelli syndrome: cutaneous hypopigmentation and silvery hair.

By courtesy of M. Canningavan, MD, University of Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree