(1)

Department of Pathology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Keywords

Temporomandibular JointHistopathology12.1 Introduction

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) allows the mobility of the mandible. The joint consist of the mandibular condyle, the fossa in the skull base and the intervening disc that ventrally is connected with the tendon of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Disorders of the mandibular joint are mostly recognized by their impairment of normal jaw mobility, leading to difficulties in chewing and mouth opening.

Pathologic tissue alterations of the joint may involve bone and cartilage, the disc or the lining synovial membrane. A surgical specimen from this area mostly consists of the mandibular condyle – partly of completely removed -, sometimes together with the disc, parts of the synovial membrane and with attached capsular fibrous tissue.

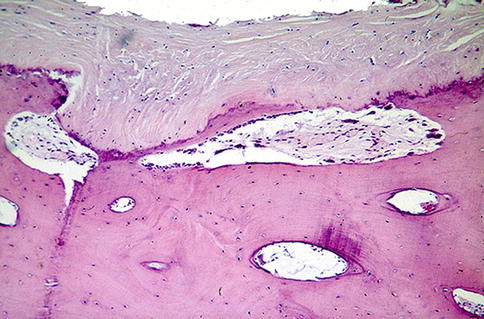

To appreciate the morphological basis of the diseases that may occur in these structures, a concise outline of their histomorphology will be given. The mandibular condyle consists of a core of cancellous bone with an outer cortical layer. The articular surface is different from most of other joints as it lack a covering layer of hyaline cartilage. Instead, the surface is formed by a fibrous layer. Between the superficial fibrous layer and the underlying bone, remnants of cell-rich mesenchyme and calcified cartilage can be observed but with increasing age, these components disappear (Fig. 12.1). Alterations in the TMJ can be classified as reactive, degenerative, inflammatory and neoplastic [1, 2].

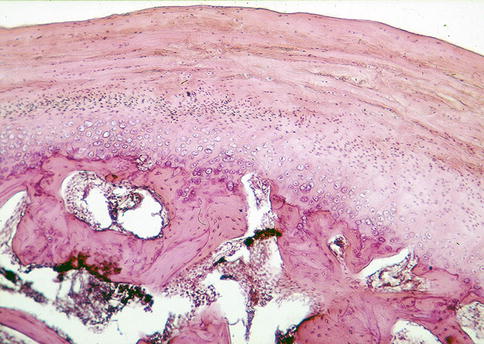

Fig. 12.1

Normal histology of the mandibular condyle. The surface is composed of fibrous cartilage. The next layer is the undifferentiated mesenchyme that is the source of cells for the fibrous cartilage above and the hyaline cartilage below. With advancing age, the undifferentiated mesenchyme disappears and the hyaline cartilage may show some calcification

12.2 Reactive Changes

The mandibular condyle is able to adapt itself to changing spatial dimensions by changing its contour through either regressive or progressive remodeling. In case of regressive remodeling, resorption cavities develop at the interface of bone and covering soft tissues, thus creating interruptions in the subchondral bone plate. The overlying soft tissue cap thus suffers from lack of support in that particular area and a concavity in the articular surface at that site is established (Fig. 12.2). In case of progressive remodeling, the superficial soft tissue layer increases and to re-establish its original thickness, a new subchondral bone plate is formed. In combination with the pre-existent subchondral bone plate, a double layered border between bone and covering tissues will develop (Fig. 12.3). When the changes in spatial dimensions are too excessive to be counteracted by remodeling, osteoarthritis develops.

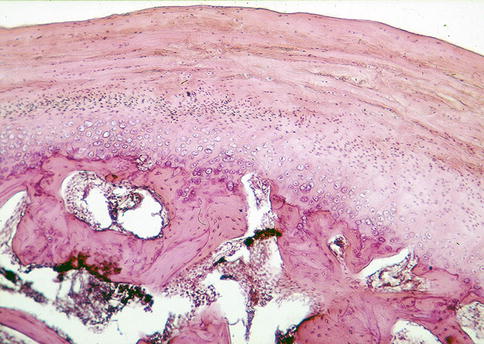

Fig. 12.2

Occurrence of regressive remodeling can be recognized by the presence of resorption cavities at the interface between bone and overlying condylar cartilage. This causes a depression in the condylar surface overlying this area

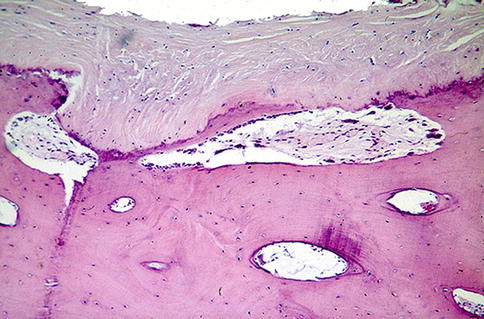

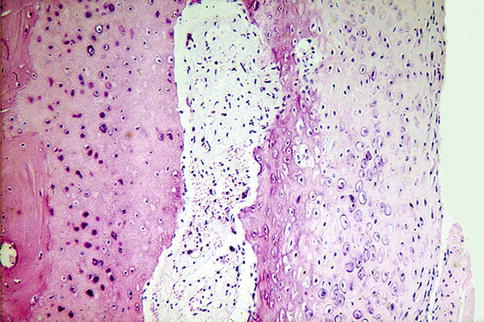

Fig. 12.3

Occurrence of progressive remodeling can be recognized by a duplication of the osteochondral junction

12.3 Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis in the TMJ does not show any changes different from those present in the hip or knee with advancing age. The fibrous tissue covering fragmentates and the exposed bone shows eburnation. Moreover, irregular proliferations of cartilage and bone may occur as a futile attempt to re-establish an intact articular surface. Through cracks in the surface, synovial fluid is squeezed into the marrow cavities and creates cavities lined by granulation tissue, also sometimes surrounded by bone resulting in the radiologically well-known subchondral bone cysts typical for degenerative joint changes (Figs. 12.4, 12.5 and 12.6).

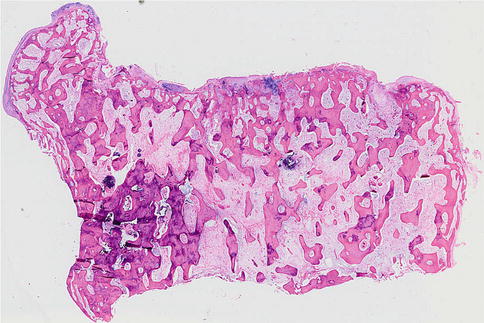

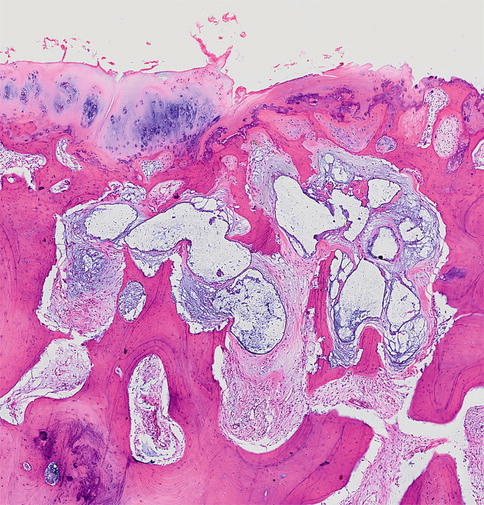

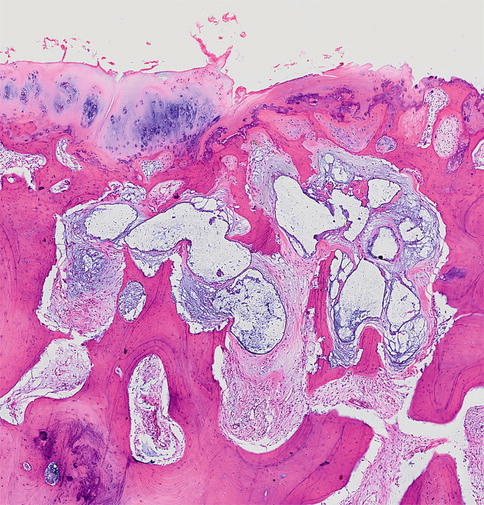

Fig. 12.4

Low power view of a mandibular condyle showing osteoarthritis. The exposed bony surface shows sclerosis and there are also remnants of cartilage. At the left side, an osteophyte covered with a cartilaginous cap is shown

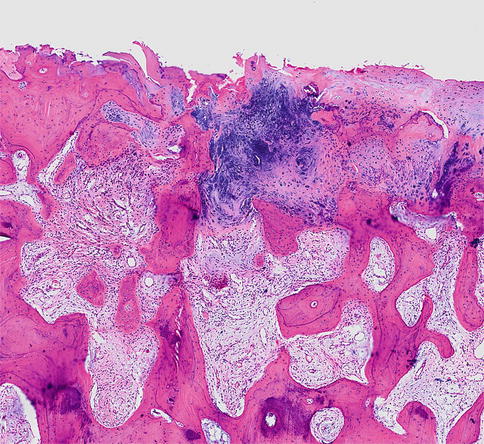

Fig. 12.5

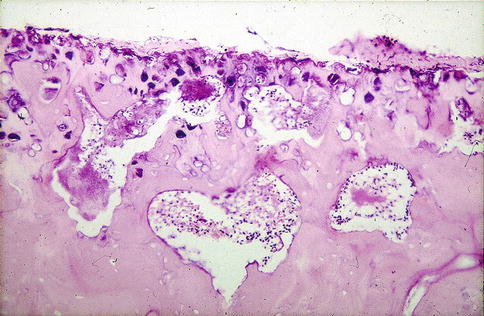

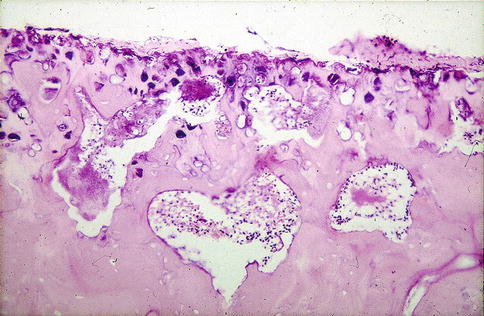

Detail of surface with osteoarthritic changes, sclerosis of subchondral as well as underlying cancellous bone and reactive proliferation of cartilaginous remnants

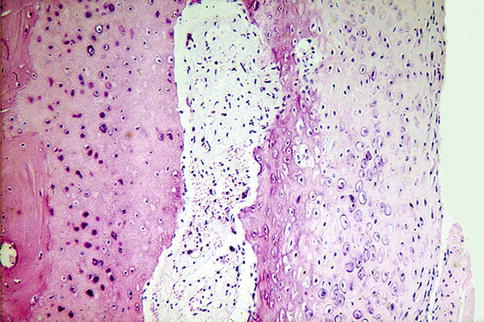

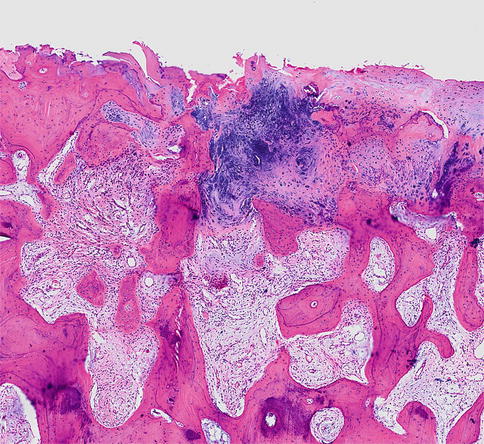

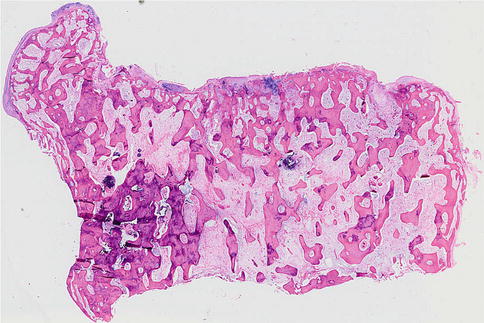

Fig. 12.6

Synovial fluid enters into the bone marrow through cracks in the articular surface; walling off through subsequent reactive changes including bone remodeling forms intramedullary pseudocysts known as subchondral bone cysts by the radiologist

12.4 Inflammatory Disorders

As any other joint, the TMJ may be afflicted by generalized joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, M. Bechterew, gout and pseudogout. More typical for the TMJ is joint disease due to continuous spread from mandibular osteomyelitis (Fig. 12.7). In case of extensive urate deposits, gout may mimic tumor (Fig. 12.8) but the presence of feathery extracellular material bordered by inflammatory cells on histological examination offers no support for a diagnosis of neoplasia (Figs. 12.9, 12.10 and 12.11). Gout and pseudogout may however evoke hypertrophic cartilaginous proliferations that can be mistaken for chondrosarcoma (Figs. 12.12 and 12.13).

Fig. 12.7

Mandibular condyle changed into a sequestrum due to osteomyelitis. Overlying soft articular layers have disappeared completely

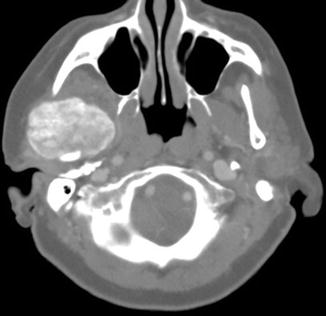

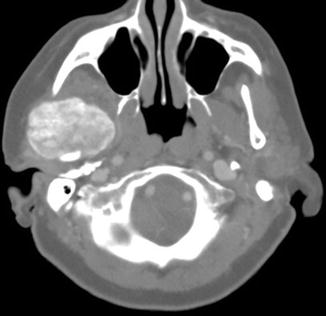

Fig. 12.8

Case of gout in the temporomandibular joint. Radiography shows space occupying lesion due to extensive deposition of urate crystals suggesting neoplasia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree