, Tsunehisa Kaku2, Toru Sugiyama3 and Steven G. Silverberg4

(1)

Matsue City Hospital, Matsue, Shimane, Japan

(2)

Department of Health Sciences, Department of Health Sciences Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Fukuoka, Fukuoka, Japan

(3)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, Morioka, Iwate, Japan

(4)

Department of Pathology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

As mentioned earlier in this volume, a very small number of the more than 600 cases submitted to our study as clear cell carcinoma (CCC) of the ovary were rejected for inappropriate histopathologic documentation, suggesting that the differential diagnosis of CCC is not a major cause of concern for most diagnostic pathologists. Of course, we have no way of knowing how many cases were not submitted because they were incorrectly diagnosed as something else, but we suspect that (at least in Japan, where CCC is a fairly common ovarian tumor and the index of suspicion is therefore high) not many cases were missed in this manner. In other countries where high-grade serous carcinoma may be ten times more common than CCC, the tendency certainly might be for an indeterminate case to be assigned to the serous rather than the clear cell category or to be called “mixed serous and clear cell” type, a term that is no longer recommended [1].

From a review in both of our own cases and of the literature, the differential diagnosis of ovarian CCC is predominantly with (in no particular order) (1) benign and borderline clear cell tumors; (2) other primary ovarian epithelial tumors, mainly carcinomas but occasionally borderline tumors; (3) ovarian germ cell and sex cord-stromal tumors; and (4) metastatic tumors in the ovary. These will be discussed in the order listed.

Although we have chosen to list and discuss benign and borderline clear cell tumors first, it is certainly not because these are either particularly common or particularly problematic. In fact, the current World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs states that clear cell cystadenoma and adenofibroma “are very rare tumors, with only a few cases reported in the literature” and that clear cell borderline tumors “comprise less than 1 % of borderline/atypical proliferative tumours” [2]. We believe that clear cell borderline tumors are even rarer than benign clear cell tumors, perhaps because we use the term “atypical clear cell cystadenoma/adenofibroma” for noninvasive clear cell tumors with focal or diffuse cytologic atypia only (Fig. 7.1). In any event, the important fact to remember is that benign-appearing clear cell tumor foci with or without (Fig. 7.2) atypia are seen frequently within CCC; it is not known whether in this situation these foci are biologically benign or malignant. On the other hand, when an ovarian tumor consists exclusively of clear cell cystadenoma, adenofibroma, or borderline tumor on initial sections, it is certainly recommended to submit additional sections to rule out CCC manifested by stromal invasion.

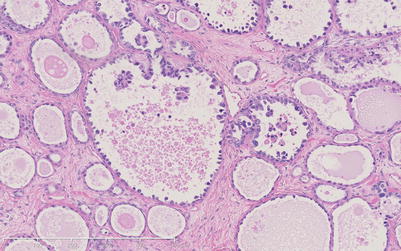

Fig. 7.1

Atypical clear cell adenofibroma focus within a clear cell adenocarcinoma. Some of the cystic glandular spaces are lined by hobnail cells with large atypical nuclei, some of which form cellular micropapillary projections within lumina. There is no evidence of stromal invasion

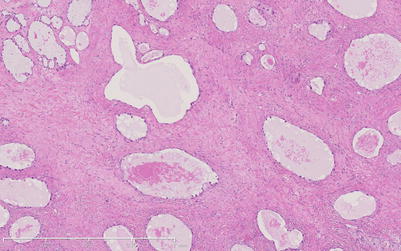

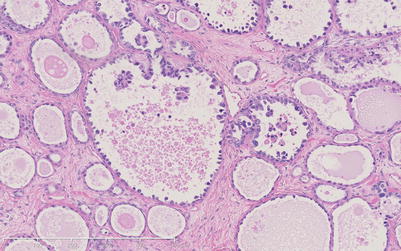

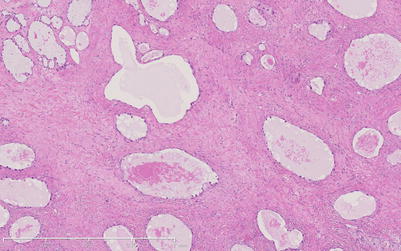

Fig. 7.2

Clear cell adenofibroma without atypia, also found as a focus within a clear cell carcinoma (CCC)

A much more common differential diagnostic problem is the distinction of CCC from other ovarian epithelial tumors, particularly high-grade serous carcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, and serous borderline tumor. As mentioned above, when an ovarian carcinoma appears to contain areas of both serous and clear cell type, it is currently considered appropriate to classify this as a serous carcinoma [1]. A few legitimate CCCs in our series, on the other hand, did contain foci which superficially resembled serous borderline tumor (Fig. 7.3). Closer examination revealed that at higher magnification, the papillary structures were lined by the usual clear and hobnail cells and hyalinization of the stroma within the papillae was also typical for CCC. Endometrioid carcinoma was a more frequent cause of exclusion from our CCC series. These two carcinomas both often originate in endometriosis and often occur together as mixed carcinomas. We allowed small amounts of endometrioid carcinoma in a clear cell carcinoma but excluded those cases with major endometrioid components. In some excluded cases, the main problem was different initial and review assessments of the relative proportions of these two elements, but in others, it appeared that secretory endometrioid foci (Fig. 7.4) or squamous components with clear cytoplasm (Fig. 7.5) had been misinterpreted as CCC. It is important to search carefully for typical areas of CCC or of endometrioid carcinoma (Fig. 7.6) within such tumors in order to make the correct diagnosis.

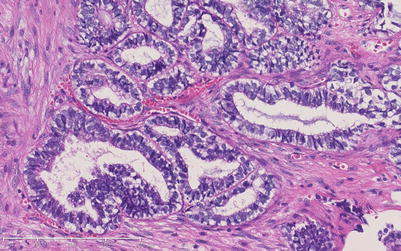

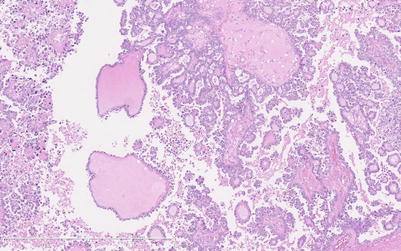

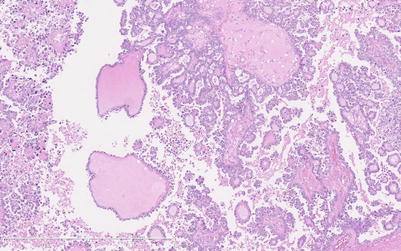

Fig. 7.3

Region within an otherwise typical CCC which resembled serous borderline tumor at low magnification, as seen here. Prominent stromal hyalinization seen here, as well as clear and hobnail cell lining of the micropapillae (better noted at higher magnification), indicates that this is a growth pattern of this CCC