Diagnostic tasks in epilepsy management include establishing a seizure diagnosis and an etiologic diagnosis and identification of precipitating factors. This is accomplished by a combination of history taking, physical examination, electroencephalography (EEG), and laboratory examinations. Common differential diagnostic problems are reviewed at the end of this chapter.

I. SEIZURE DIAGNOSIS

The first step in managing a patient for whom a diagnosis of epilepsy is possible is establishing definitively whether the patient has epilepsy. Patients who are erroneously diagnosed with epilepsy will be unnecessarily subjected to many inconveniences, including medication that may produce serious side effects, expensive laboratory tests, loss of a driver’s license, and possible loss of employment. Specific differential-diagnostic entities that must be differentiated from seizures are discussed in

section IX.

If a patient has epilepsy, accurately determining which type(s) of epileptic seizure the patient has is crucial, so that he or she can be given correct therapy. The diagnosis of seizure type should be made according to the International Classification of Epileptic Seizures, reviewed briefly in

Chapter 1 and in detail in

Chapter 2. The specific epilepsy syndrome should also be identified, as treatment of a given seizure type may vary among the specific epilepsy syndromes. For example, tonic-clonic seizures as part of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy are often treated differently from tonic-clonic seizures as part of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy.

II. ETIOLOGIC DIAGNOSIS

Epilepsy is a symptom, not a disease. A seizure can be a symptom of old or recent cerebral trauma, a brain tumor, a brain abscess, encephalitis, meningitis, a metabolic disturbance, drug intoxication, drug withdrawal, and many other disease processes. It is imperative that the underlying cause of a patient’s seizure be identified and treated, so that a reversible cerebral disease process is not overlooked, and seizure control can be facilitated.

III. PRECIPITATING FACTORS

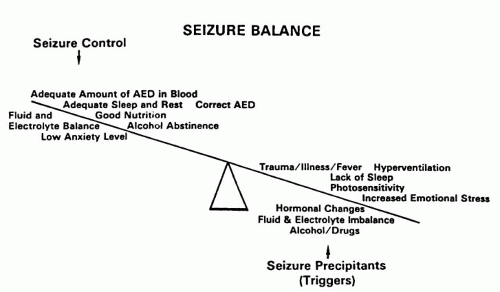

In addition to determining the underlying cause(s) of a patient’s seizure disorder, identifying and managing factors that precipitate seizures in a given individual, such as anxiety, sleep deprivation, and alcohol withdrawal (

Fig. 9-1), also are important. Management of such precipitating factors reduces seizure frequency and the patient’s need for medication.

IV. HISTORY

The best way to diagnose which type of seizure a patient has is actually to observe a seizure, although the physician usually does not have the opportunity to do so. Often, the most important differential-diagnostic information is contained in the history gathered from the patient, reliable observers, or both. Family members and friends of the patient should be encouraged to try to videotape the events, when possible.

The history for seizure diagnosis should include exact details of events before, during, and after the seizure, obtained from the patient and observers. Partial seizure symptoms and signs (motor, sensory, autonomic, psychic); alteration of consciousness; automatisms; tonic movements, clonic movements, or both; tongue biting; incontinence; and postictal behavior are important details. The duration, time of occurrence (e.g., on awakening, when drowsy, during sleep), and frequency of seizures also are important. For example, tonic-clonic seizures occurring during the first few hours of sleep are usually secondarily generalized, whereas tonic-clonic seizures occurring on awakening are usually primarily generalized. Past or current occurrence of other seizure types (especially myoclonic or absence) often is not volunteered by the patient and should be specifically solicited. Specific questions regarding entities that may be confused with seizures are discussed later, in

section IX.

The history for etiology should include questions regarding family history of epilepsy, head trauma, birth complications, febrile convulsions, middle ear and sinus infections (which may erode through bone and cause cerebral focus), alcohol or drug abuse, and symptoms of malignancy.

The history for precipitating factors should include factors such as fever, anxiety, sleep deprivation, menstrual cycle, alcohol, hyperventilation, flickering lights, or television (

Fig. 9-1).

V. PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Although neuroimaging has supplanted the neurologic examination in the eyes of some, the value of the examination should not be underestimated. A detailed physical and neurologic examination can frequently point to the etiology of the epilepsy. The physical examination should be directed toward uncovering evidence of past or recent head trauma; infections of the ears and sinuses; congenital abnormalities (e.g., hemiatrophy, stigmata of tuberous sclerosis); focal or diffuse neurologic abnormalities; stigmata of alcohol or drug abuse; and signs of malignancy. Subtle but “hard” findings may be useful in uncovering evidence of focal brain dysfunction indicative of symptomatic focal epilepsy. Such findings include facial asymmetry, asymmetry of thumb size (indicates contralateral cerebral damage during infancy or child-hood), drift or pronation of outstretched hands, dystonic posture when walking on sides of feet, or naming difficulty (left temporal dysfunction). Finally, 3 minutes of vigorous hyperventilation usually produces absence seizures in untreated absence seizure patients.

VI. ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

The EEG is a helpful diagnostic tool in the investigation of a seizure disorder. It confirms the presence of abnormal electrical activity, gives information regarding the type of seizure disorder, and discloses the location of the seizure focus. Both routine (paper tracing) and digital recording techniques are in regular use. In some instances, the routine EEG is normal, although the patient has seizures or is suspected of having them. Under these circumstances, the study is repeated after the patient is deprived of sleep (4 hours or less of sleep the night before the study), and special (e.g., temporal or sphenoidal) leads also may be used. This procedure is helpful in bringing out the abnormality in many cases, especially if discharges arise from the temporal lobe.

If the history unequivocally points to a seizure disorder, the patient should be treated despite normal waking and sleep-deprived EEGs. The usual EEG study samples only roughly 1 hour of time and is normal in a significant percentage of patients with epilepsy. In cases in which whether a patient has seizures is uncertain or the seizure type cannot be determined despite a careful history, physical examination, and routine waking and sleep-deprived EEGs, the diagnosis often can be established by prolonged monitoring of the EEG.

VII. LABORATORY EXAMINATION (INCLUDING NEUROIMAGING)

Usually, the following laboratory tests should be performed in evaluating the cause of a newly diagnosed seizure disorder: metabolic screen, EEG recording in waking and sleep states, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomographic (CT) scan. MRI is preferred over CT because of its greater sensitivity and specificity for identifying small lesions. A toxic screen should be performed if alcohol or drug abuse or withdrawal is suspected. A lumbar puncture (for opening pressure, cell counts,

protein, glucose, cytology, culture, and serology) should be performed if infection or malignancy is suspected.

The American Academy of Neurology has published practice parameters for neuroimaging (NI) studies (MRI, CT) of patients having a first seizure. Emergency NI (scan immediately) should be performed when a health care provider suspects a serious structural lesion. Clinical studies have shown a higher frequency of life-threatening lesions in patients with new focal deficits, persistent altered mental status (with or without intoxication), fever, recent trauma, persistent headache, history of cancer, history of anticoagulation, or suspicion of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Urgent NI (scan is included in the disposition or is performed before disposition when follow-up of the patient’s neurologic problem cannot be ensured) should be considered for patients who have completely recovered from their seizure and for whose seizures no clear-cut cause (e.g., hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, tricyclic overdose) has been identified to help determine a possible structural source. Because adequate follow-up is needed to ensure a patient’s neurologic health, urgent NI may be obtained before disposition when timely follow-up cannot be ensured.

Additionally, for patients with first-time seizure, emergency NI should be considered if the patient is older than 40 years or has had partial-onset seizures.

MRI and CT are the two imaging techniques used in routine diagnosis and management of epilepsy. A number of specialized imaging studies are used for localizing seizure-producing lesions for purposes of surgical resection. These studies include single-photon emission CT (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and magnetoencephalography (MEG). These specialized tests are discussed in

Chapter 10.

VIII. SYNTHESIS OF DATA

By combining history, physical examination, and EEG information, the health care provider should be able to determine (a) whether the patient’s events are seizures and (b) the patient’s seizure type(s) according to the International Classification of Epileptic Seizures (see

Chapter 2, Table 2-1). If this cannot be done, additional history (e.g., additional witnesses) or additional EEG (e.g., long-term EEG monitoring) information, or both, should be obtained. If all possible information has been gathered and the diagnosis remains uncertain, the health care provider usually is forced to act on the basis of available history. If the history strongly suggests a recurrent seizure type, a therapeutic trial of antiepileptic medication appropriate for the seizure type is usually begun. If the history does not strongly suggest recurrent seizures, observation without medication is the usual plan. Management of a patient having a single seizure is discussed in

Chapter 10.

Seizure type combined with additional information from history, physical examination, EEG, and laboratory tests often allows determination of the patient’s specific epilepsy syndrome according to the International Classification of Epilepsies and

Epileptic Syndromes. This determination assists with selection of therapy and counseling regarding prognosis and familial occurrence.

IX. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF EPILEPSY

The common differential diagnostic problems associated with epilepsy at various ages are shown in

Table 9-1.

A. All Ages

1. Epilepsy Versus Migraine

A. COMMON FEATURES.

Episodic occurrence, headache, sensory (visual, paresthesias) or motor (weakness) aura, loss of consciousness (basilar migraine), and focal slowing on EEG are all common features of both epilepsy and migraine. Both disorders are common, and they can occur in the same patient.

B. FEATURES SUGGESTING EPILEPSY.

Absent or less severe headache, bilateral and nonpulsatile; paroxysmal activity on interictal and ictal EEG (spikes, sharp waves, spike-waves); and persistent slowing on interictal EEG are features suggesting epilepsy.

C. FEATURES SUGGESTING MIGRAINE.

Severe unilateral, pulsatile headache; nausea and vomiting; photophobia; family history of migraine; and EEG slowing only during or immediately after an attack are features suggesting migraine.

D. OTHER.

The neurologic auras of migraine may occur with or without headache. A large and conflicting literature exists on the EEG in migraine. Patients with only migraine may have paroxysmally abnormal EEGs. Abdominal epilepsy and abdominal migraine are discussed in

section IX.B.6.

E. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS.

The differential diagnosis is listed in

Table 9-2.

2. Epilepsy Versus Syncope

A. DEFINITIONS.

Syncope, or fainting, is the sudden loss of muscle tone, collapse of posture, and loss of consciousness associated with a decrease in systemic blood pressure. Syncopal attacks begin with a clouding of consciousness accompanied by vertigo, nausea, and a waxy pallor of the skin. The attack usually lasts approximately 10 seconds.

Syncope can occur because of one of two mechanisms: autonomic failure and neural mediation. In autonomic failure, sympathetic efferent activity is chronically impaired, so that vasoconstriction is deficient. On standing, blood pressure always decreases (i.e., orthostatic hypotension), and syncope or presyncope occurs. In neurally mediated syncope, the failure of symptomatic efferent vasoconstriction traffic (and hypotension) occurs episodically in response to a trigger. Between syncopal episodes, the patients have normal blood pressure and orthostatic responses.

Convulsive syncope has an onset similar to that of a typical syncopal attack. However, the onset is followed by a tonic spasm in which the back, head, and lower limbs are bent backward and the fists are clenched. This is often accompanied by mydriasis, nystagmus, drooling of saliva, and incontinence. The patient may bite his or her tongue, although this is rare.

The patient who falls to the floor quickly recovers from a faint when the blood pressure is reestablished. If the person is unable to reach the supine position, as when fainting occurs in a chair or in a phone booth, cerebral circulation is reestablished more slowly. Under these conditions, convulsive syncope is more likely to occur.

B. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS.