Chapter 36 Diabetes mellitus, insulin, oral antidiabetes agents, obesity

History of insulin therapy in diabetes

Diabetes was known to ancient Greek medicine with the description of ‘a melting of the flesh and limbs into urine … the patients never stop making water but the flow is incessant … their mouth becomes parched and their body dry’.1

Many doctors, after they have developed a disease, take up the speciality in it … But that was not so with me. I was studying for surgery when diabetes took me up. The great book of Joslin said that by starving you might live four years with luck. [He went to Italy and, whilst his health was declining there, he received a letter from a biochemist friend which said] there was something called ‘insulin’ appearing with a good name in Canada, what about going there and getting it. I said ‘No thank you; I’ve tried too many quackeries for diabetes; I’ll wait and see’. Then I got peripheral neuritis … So when [the friend] cabled me and said, ‘I’ve got insulin – it works – come back quick’, I responded, arrived at King’s College Hospital, London, and went to the laboratory as soon as it opened … It was all experimental for [neither of us] knew a thing about it … So we decided to have 20 units a nice round figure. I had a nice breakfast. I had bacon and eggs and toast made on the Bunsen. I hadn’t eaten bread for months and months … by 3 o’clock in the afternoon my urine was quite sugar free. That hadn’t happened for many months. So we gave a cheer for Banting and Best.2

But at 4 pm I had a terrible shaky feeling and a terrible sweat and hunger pain. That was my first experience of hypoglycaemia. We remembered that Banting and Best had described an overdose of insulin in dogs. So I had some sugar and a biscuit and soon got quite well, thank you.3

Diabetes mellitus is classified broadly as:

• Type 1 (formerly, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, IDDM) which typically occurs in younger people who cannot secrete insulin.

• Type 2 (formerly, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, NIDDM), which usually occurs in older people who are typically (although not always) obese. Type 2 diabetes is best thought of as a group of conditions characterised by a variable combination of reduced insulin secretion and resistance to insulin’s blood glucose lowering action.

• Other causes: including gestational diabetes, disease processes affecting the liver or pancreas such as cystic fibrosis causing a ‘secondary’ diabetes, monogenic forms (maturity onset diabetes of the young, MODY).

Sources of insulin

• Bovine insulin differs from human insulin by three amino acids.

• Porcine insulin differs from human by only one amino acid.

• Human insulin is made either by enzyme modification of porcine insulin, or by using recombinant DNA to synthesise the pro-insulin precursor molecule for insulin. This is done by artificially introducing the DNA into either Escherichia coli or yeast.4

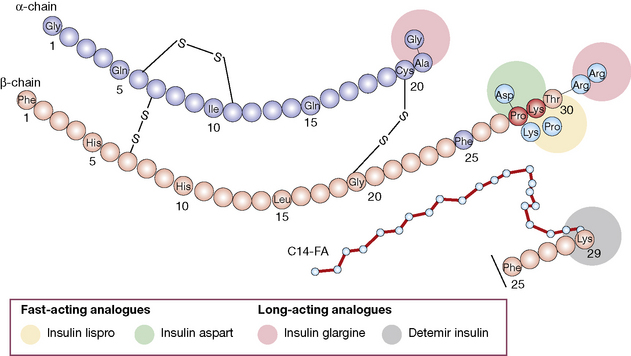

• Insulin analogues are now widely used and have modifications introduced to the A and/or B chains, which result in more rapid onset and offset of action (rapidly acting analogues), or slower offset (long acting analogues) than naturally occurring insulin.

Actions of insulin

• Reduction in blood glucose is due to increased glucose uptake in peripheral tissues (which oxidise glucose or convert into glycogen or fat), and a reduction in hepatic output of glucose (diminished breakdown/increased synthesis of glycogen and diminished gluconeogenesis).

• Other metabolic effects. Although, therapeutically, insulin is thought of as a blood glucose lowering hormone, it has a number of other cellular actions. Insulin is an anabolic hormone, enhancing protein synthesis (which has resulted in cases of misuse by bodybuilders). It also inhibits both breakdown of fats (lipolysis) and ketogenesis. Insulin also has actions on electrolytes, stimulating potassium uptake into cells and renal sodium retention (anti-natriuretic effect). Within brain, insulin may have actions to stimulate memory and act as a nutritional signal to help control appetite/food intake.

Uses

• Diabetes mellitus is the main indication.

• Insulin promotes the passage of potassium into cells by stimulating cell surface Na/K ATPase action, and this effect is utilised to correct hyperkalaemia (see p. 458).

• Insulin-induced hypoglycaemia can also be used as a stress test of anterior pituitary function (growth hormone and corticotropin and thus cortisol are released).

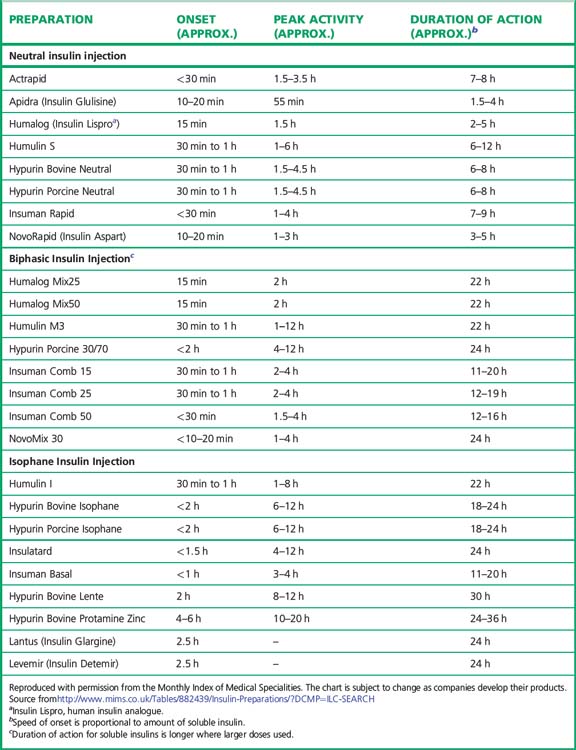

Preparations of insulin (Table 36.1)

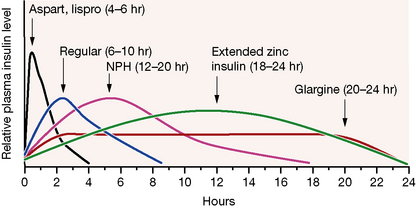

Broadly speaking, four different types of insulin with differing time-courses of action are available for treating diabetes (illustrated in Fig. 36.1):

1. Short duration of action (and rapid onset). Soluble insulin (also called neutral or regular insulin). The most recent additions to this class of insulin, lispro, aspart and glulisine, are modified human insulins with changes in the B chain resulting in more rapid absorption after subcutaneous injection and thus a faster onset and shorter duration of action.

2. Intermediate duration of action (and slower onset). Preparations in which the insulin has been modified physically by combination with protamine or zinc to give an amorphous or crystalline suspension; this is given subcutaneously and slowly dissociates to release insulin in its soluble form. Isophane (NPH) insulin, a suspension with protamine, is still widely used. Insulin Zinc Suspensions (amorphous or a mixture of amorphous and crystalline) are now rarely used.

3. Longer duration of action. Newer analogues glargine and detemir (Fig. 36.2) have become widely used, especially in type 1 diabetes. Small changes in the amino acid structure of glargine result in a significant slowing of absorption from subcutaneous depots. In contrast, detemir owes its protracted action to fatty acylation. After absorption, detemir is thus bound to circulating albumin which delays its action.

4. A biphasic mixture of soluble or short acting analogue insulin with isophane insulin.

Choice of insulin regimen

1. ‘Basal bolus’ therapy: multiple injections of short acting insulin are given during the day to mimic prandial secretion of insulin by the pancreas, combined with once or twice daily intermediate or long acting insulin to provide the background insulin. This approach aims to mimic the non-diabetic pattern of insulin release. The total insulin dose is usually apportioned to be 40–60% background and 40–60% prandial.

When choosing the short acting insulin in a basal bolus regimen, soluble insulin is given 30 min before meals. Short acting analogues may be given immediately before, during or even after the meal, although recent data suggest that even these insulins may be more effective if given 15 min prior to eating. The more rapid waning of action profile also means that the risk of hypoglycaemic reactions before the next meal may be lower with the analogues. For choice of background insulin, long acting analogues may give less risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia than NPH insulin (see Fig. 36.1) although NPH insulins offer greater flexibility if patients need to change background insulin from day to day (as with some sportsmen or pregnant women, for example).

2. Twice daily therapy involves two injections of biphasic insulin. Although less ‘physiological’ than basal bolus, it is simpler, with fewer insulin injections. The available mixtures are listed in Table 36.1. The most commonly used is 30:70 (soluble: NPH). Typically half to two-thirds of the daily dose may be given in the morning before breakfast and half to one-third before the evening meal. A combination of biphasic insulin with breakfast and fast acting insulin with evening meal and bedtime background insulin may be useful in some children with type 1 diabetes to avoid having to inject insulin at school.

3. Background or prandial insulin alone may be sufficient in type 2 diabetes when patients progress from oral therapy on to insulin. In this situation, oral therapy is usually continued in combination with insulin.