![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Recognize the role of pharmacists in diabetes management services.

2. Define diabetes.

3. Review the goals of diabetes management.

4. Identify key concepts in diabetes management.

5. Discuss ways to prepare for clinic initiation.

6. Identify aspects to consider when developing a business plan.

7. Discuss clinic design.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a devastating disease affecting nearly 25.8 million people, which corresponds to roughly 8.3% of the U.S. population.1 Of the 25.8 million affected, it is estimated that nearly 7 million are undiagnosed.1 In 2007, diabetes was labeled the 7th leading cause of death based on death certificates, which was likely underreported as a primary cause of death.1 Overall, the risk of death is doubled for patients with diabetes compared with those without.1 Complications resulting from diabetes may include heart disease, stroke, blindness, kidney disease, amputations, dental disease, and pregnancy complications.1 Notably, diabetes is the leading cause of new cases of blindness in adults 20–74 years of age, accounts for 44% of all new cases of kidney failure, and is the cause of >60% of nontraumatic lower-extremity amputations.1 According to a national survey in 2007–2009, Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanic/Latinos age 20 years or older comprised the highest percentage of the population with diabetes (13.8%, 13.3%, 12.6%, and 11.8%, respectively).1 Non-Hispanic whites made up 7.1%, while Cuban Americans and Central and South Americans each made up 7.6% of the population of patients over 20 years of age with diabetes.1 The increased prevalence in minority populations may be due to genetic factors, lower income status, or lack of access to health-care. Community pharmacist-delivered pharmaceutical care is one way to help address this disparity and increase access to care for some of these patients.

The total cost of diabetes was estimated in 2007 to be at least $174 billion, with $27 billion used to treat diabetes directly, $58 billion to treat chronic complications related to diabetes, $31 billion in excess medical costs, and $58 billion accounting for reduced national productivity.2 On average about $1 in $5 health-care dollars was spent caring for someone with diabetes, while $1 in $10 health-care dollars was attributed directly to diabetes.2 The average annual expenditures attributed to the disease were estimated at $6649 in 2007.2

When diabetes is uncontrolled there is a greater likelihood of a rise in complications, which in turn can lead to increases in costs. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 35), which was reported in 2000, found a reduced incidence of microvascular complications (including neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy) in patients with type 2 diabetes that achieved intensive glycemic control.3 For every 1% decrease in mean hemoglobin A1C (A1C), there was an associated 37% reduction in risk of microvascular complications, 14% reduction in risk of myocardial infarction, and 21% reduction in risk of any end point related to diabetes.3 Additionally, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) concluded that intensive diabetes therapy successfully slows the progression and onset of diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes.4 In 1997, Gilmer and colleagues looked at medical care charges for 3017 adults with diabetes over 4 years and found that charges increased for every 1% increase above A1C of 7%.5 As the A1C increased, the increase in charges also escalated.5 It is evident from these findings that glycemic control helps reduce both complications and costs associated with diabetes.

With the steady rise in diabetes over the past decade, it is projected that by 2050 the prevalence of diabetes will increase from 14% to between 21% and 33% of the adult population.6 This rise is expected to be at least partially due to the increasing size of high-risk minority populations and the aging of the population.6 The burden of diabetes is rapidly growing and placing a significant impact on the health-care system as well as the quality of life for these individuals.

Pharmacists in a variety of practice settings can be an integral part of managing patients with diabetes or identifying those patients at a high risk of developing diabetes. Pharmacists are exposed to rigorous curriculums that prepare them not only to be medication experts but also to effectively manage patients with chronic disease states, such as diabetes. With the increasing number of patients affected by diabetes and amount of education and attention needed to properly manage these patients, combined with shortage of primary care providers, patients may not be receiving adequate diabetes education or management. Pharmacists are well positioned and qualified to help fill this gap in care experienced by many patients. Having a pharmacist as part of the diabetes care team allows the practitioner to see more patients with acute problems while still having the large number of patients with chronic conditions managed. The Asheville Project is a prime example of how community pharmacists have positively impacted the health of employees with diabetes. In this study, pharmacists provided community-based pharmaceutical care services for self-insured employees of the City of Asheville, NC.7 Average A1C decreased overall in these patients and total direct medical costs decreased by $1200 to $1872 per patient per year when compared with baseline.7 The City of Asheville also noted an increase in productivity valued at $18,000.7 Another study showing positive results from pharmacist interventions in patients with diabetes compared 87 men with diabetes who were managed by physician-supervised pharmacists to 85 similar patients who did not receive pharmacist care, but were managed in the same health-care system between October 1997 and June 2000.8 The relative risk of achieving an A1C of ≤7% was significantly higher in the pharmacist-managed group versus the control group (RR 5.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.62–10.26).8 The average frequency of unscheduled diabetes-related visits/patient/year was also significantly higher in the nonpharmacist managed group when compared with the pharmacist-managed cohort (1.33 +/– 3.74, 0.11 +/– 0.46, p + 0.003).8 The evidence clearly demonstrates the positive impact of pharmacists’ contributions to diabetes management. Many opportunities exist for pharmacists to provide innovative diabetes management services.

THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES

THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT OF DIABETES

Categories and Goals of Diabetes Mellitus and Concomitant Disease States

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) classifies diabetes mellitus into four separate categories, including (1) type 1 diabetes, resulting from β cell destruction; (2) type 2 diabetes, resulting from progressive insulin resistance and reduced insulin secretion; (3) diabetes due to other causes, such as genetic defects in β cell function or insulin action; or (4) gestational diabetes, diagnosed during pregnancy. Because approximately 90% of all patients with diabetes in the United States have type 2, this chapter will focus on the care and management of patients in this category. However, the goal and management of patients with type 1 diabetes is the same as those with type 2. Both are chronic illnesses that require continuous medication therapy management (MTM) and medical care, along with intensive counseling and patient self-management to decrease the risk of long-term complications.9

Diagnosis

Although pharmacists are not diagnosticians, pharmacists should be aware of the diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Test results of one of the following would be diagnostic for diabetes, after a repeat test is completed for verification: (1) A1C ≥6.5%; (2) fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL; (3) oral glucose tolerance test ≥200 mg/dL; or (4) a random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL (in a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia). Point-of-care (POC) A1C assays are widely available, but the ADA cautions that these assays are not sufficiently accurate for diagnosing diabetes. However, POC can be used for diabetes screenings or to determine treatment changes.9

Overall Goals

The major goal for most patients with diabetes is to decrease A1C to <7%. This has been shown consistently in many studies to decrease microvascular complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.9 If achieved soon after diagnosis, this goal has been associated with long-term reduction in macrovascular complications as well. Macrovascular complications include cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. However, a more stringent goal of <6.5% is reasonable for selected patients, usually younger with a short duration of diabetes, long life expectancy, and no significant CVD. Hypoglycemia has been associated with an increased risk of death; thus, clinicians should be cognizant of hypoglycemia in certain populations. These are generally older patients with long-standing diabetes and/or a history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, comorbidities, and advanced micro- or macrovascular complications. For these latter patients, a less stringent goal of A1C <8% would be reasonable. Patient attitude and expected treatment outcomes are also important determining factors for the approach to hyperglycemia management. Those who are highly motivated, adherent, with excellent ability to perform self-care management and a good support system should be able to achieve more stringent goals.10

Concomitant Disease State Goals

CVD associated with macrovascular complications is a major cause of morbidity and mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes. However, controlling the concomitant disease states of hypertension and hyperlipidemia is as important as achieving the goal A1C. Both are independent risk factors for CVD in the patient with diabetes, each with their own separate goals. In particular, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) suggests that by preventing the micro- and macrovascular complications associated with diabetes, control of hypertension has the most significant impact on morbidity and mortality.11

According to ADA recommendations, blood pressure for patients with diabetes should be measured at each visit. A goal blood pressure of <140/80 mm Hg is appropriate for most patients with diabetes and concomitant hypertension. Lower goal targets (<130/80 mm Hg) may be appropriate for some, such as younger patients, if this can be achieved without significant adverse events. Lifestyle changes should be suggested if the blood pressure is > 120/80 mm Hg. If patients have a blood pressure ≥140/80 mm Hg, prompt initiation of medication along with lifestyle therapy should occur. Multiple agents may be needed to achieve significant blood pressure reduction. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) may be used as first-line agents for controlling hypertension due to the high CVD risk associated in patients with diabetes. Also, many patients with hypertension require multiple-drug therapy to reach treatment goals. A variety of antihypertensive agents are valuable in reducing cardiovascular effects, including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, β-blockers, and calcium channel blockers. Selection could be based on other comorbidities (e.g., CVD, heart failure, and post-myocardial infarctions), presence of albuminuria, potential metabolic adverse effects, pill burden, adherence, and cost.9

Fasting lipid profiles should be measured at least annually with the following goals for patients with diabetes: low-density lipoprotein (LDL) <100 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) >40 mg/dL in men and >50 mg/dL in women, and triglycerides (TG) <150 mg/dL.9 To improve the lipid profile, lifestyle modifications should be recommended as the cornerstone of therapy. In addition, for individuals under 40 years of age and without overt CVD, therapy with a statin should be started if the LDL is >100 mg/dL. A statin should be started, regardless of baseline lipid levels, for any patient with diabetes who has overt CVD.12

If the individual without overt CVD is under 40 years of age (i.e., lower risk patients), LDL cholesterol >100 mg/dL could require implementation of a statin in addition to lifestyle therapy. In patients with overt CVD, attempting to attain a more stringent LDL goal of <70 mg/dL is an option. While it is reasonable to strive for the goals of all fasting lipid profile components, LDL-targeted therapy using a statin is preferred. If target goals of therapy are not achieved with maximum statin therapy (or maximum doses cannot be tolerated), a 30 to 40% reduction in baseline LDL goal is reasonable. Combination therapy with a statin has not been shown to provide additional cardiovascular benefit in comparison to a statin alone, and is not recommended.9

Other recommendations for patients with diabetes include the use of antiplatelet agents and smoking cessation. Daily therapy with an 81 mg strength aspirin is recommended as secondary prevention for all patients with diabetes and a history of CVD. For those without CVD, primary prevention is not as clear-cut. If patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes are at increased cardiovascular risk (i.e., 10-year risk is >10%), daily aspirin therapy is recommended. These patients would include men 50 years of age or older and women 60 years of age or older with at least one other major risk factor including: hypertension, family history of CVD, smoking, dyslipidemia, or albuminuria. For younger patients without additional risk factors, the risk of bleeding will outweigh the benefits of daily aspirin therapy. For those with an allergy to aspirin, clopidogrel may be used as an alternative.9

Smoking cessation is encouraged for all patients with diabetes. Tobacco users with diabetes have an increased risk of CVD and mortality rates, and a quicker propensity to develop microvascular complications. Neuropathy, in particular, is problematic in smokers with diabetes. Smoking also may be correlated to development of type 2 diabetes. Of interest, blood glucose levels can increase in the short-term post-cessation, while reductions in A1C and mortality are benefits in the long-term.9 Smoking cessation may be particularly difficult, as patients with diabetes may view tobacco use as part of a weight-control tool. However, these patients must be assured that the long-term benefits of A1C and mortality reduction strongly favor cessation. Smoking also increases insulin metabolism, possibly increasing insulin doses required for control. Smokers with diabetes should be offered cessation medications along with support counseling, as both together are more effective than either alone. Also, combination cessation therapy may be needed in this special population. Using cessation medications that do not cause weight gain, such as bupropion SR, may also be considered.9

Primary Counseling Concepts

Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia

Patients with diabetes should know the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, and the resultant action to take, as either condition can be life-threatening.

Hypoglycemia can be a significant barrier in achieving A1C goals. When titrating insulin, sulfonylureas, or meglitinides, or when patients do not manage meals or exercise regimens properly, hypoglycemia can result. These symptoms can be especially unnerving during a first-time experience. Hypoglycemia should be discussed during an initial visit because medications will be titrated to achieve the A1C goal. Hypoglycemia is an acute circumstance that must be addressed immediately. The symptoms of hypoglycemia include shakiness, nervousness, hunger, sweating, dizziness, confusion, anxiety, or weakness. For many patients, hypoglycemia may be experienced when blood glucose levels drop <70 mg/dL, with symptoms if blood glucose is <60 mg/dL.9,10

When symptoms occur, patients should promptly check the blood glucose. The preferred form of treatment is 15 g of glucose, usually three or four tablets, depending on the brand. Other options for treatment include four ounces of juice or sugar-sweetened soda or eight ounces of low-fat milk. If the blood glucose has not increased to an acceptable level after 15 minutes, the treatment regimen should be repeated. Once blood glucose has normalized, the patient can then eat a small meal or snack containing protein and carbohydrate to prevent any recurrence. For the patient at risk for severe hypoglycemia, a glucagon kit should be prescribed and administration instructions taught to family members and caregivers. Glucagon should be administered when patients are unable to swallow or are unconscious due to hypoglycemia. Also, the pharmacist should monitor for medications that could cause hypoglycemia unawareness, such as β-blockers. This class of antihypertensives is not contraindicated for patients with diabetes, but sweating may be the only indication of hypoglycemia when a β-blocker is used. The pharmacist should ensure that such patients maintain awareness when the blood glucose runs low. If the patient has hypoglycemia unawareness, short-term allowance of higher glycemic targets is in order. After several weeks of higher blood glucose levels, counter-regulation and awareness of hypoglycemic symptoms may be improved.9

Hypoglycemia may be experienced at relatively higher blood glucose levels when A1C is greatly elevated at baseline. These patients may “just feel better” when their blood glucose levels are elevated and may be more reluctant to titrating medications. Titration may be “uncomfortable” for these patients at first, but they should be counseled to treat for hypoglycemia only when blood glucose levels are less than 70 mg/dL. They should be reassured that they will become more accustomed to this lower “set point” for hypoglycemia, and that hyperglycemic complications could occur if the medications are not titrated. Until the patients become accustomed to lower blood glucose levels, half of a usual treatment dose for hypoglycemia (e.g., two ounces of orange juice rather than four ounces) could be recommended.9,10

Another common mistake concerning hypoglycemia is when a patient withholds insulin inappropriately. Patients are often uncomfortable giving insulin injections when the blood glucose is below a certain level. This results in withholding long-acting insulin, with later glucose levels in the day being greatly elevated. Patients should be counseled to administer long-acting insulin to prevent elevated blood glucose levels later in the day—unless blood glucose levels are low (e.g., less than 50 or 60 mg/dL) and the patient is having difficulty increasing the blood glucose levels. Short-acting insulin doses should be withheld if hypoglycemia is occurring, and the hypoglycemia should be treated. Then, as the hypoglycemia is resolved, a normal schedule of insulin injections can be implemented along with a normalized meal schedule.

A patient experiencing hyperglycemia should be counseled to contact the provider. Hyperglycemia is not necessarily an acute event, unless associated with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome (HHNS) or ketoacidosis. The classic symptoms of hyperglycemia are polyuria (excessive urination), polyphagia (excessive hunger/eating), and polydipsia (excessive thirst/drinking). Other symptoms may include blurred vision, weight loss, fatigue, dry mouth, pruritus, frequent urinary tract infections, and poor wound healing. The patient should have a plan in place with their medical provider if they begin to experience these symptoms along with elevated blood glucose levels.9,10

Lifestyle Modifications—Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) and Exercise

Lifestyle modifications are the cornerstone of management for all patients with diabetes. This is often the most difficult aspect of MTM for patients with diabetes because most are overweight and will need significant behavioral modification. Achieving weight loss is an important goal; even a modest weight loss of 5–10% is associated with improved glycemic control and reduced insulin resistance. Many patients believe that this goal should be much higher and may become discouraged when the weight does not immediately respond to initial efforts. A sustained 1% weight loss per week is the most achievable goal in the long term. However, to achieve and maintain weight loss goals, patients should implement both components of lifestyle modification—MNT and exercise.9,10

For MNT, diets low in carbohydrates and fats, restricted in calories, or Mediterranean diets may be efficacious in the short term. Although a “fad” diet may be tempting, the long-term effectiveness is poor. Moreover, the long-term health effect of very-low-carbohydrate diets is unclear. Instead, dietary improvements should become a way of life. The best mix of the macronutrients carbohydrate, protein, and fat will vary according to the individual. An individualized meal plan based on population-wide dietary recommendations and the patient’s culture and preferences should be recommended. High-fiber foods (vegetables, some fruits, whole grains, and legumes) and lean meats should be a large part of the diet. Conversely, foods high in saturated fats and sugar-sweetened drinks, desserts, and snacks should be greatly minimized. Attention should be given to total carbohydrate intake, whether by counting carbohydrates, calculating carbohydrate choices, or another method. Clinical studies have documented that effective MNT programs can reduce the A1C from 0.25% to 2.9% in even short periods of time.9,10

Two common problems that many people have upon first starting lifestyle modifications are that they consume sugar-sweetened beverages and eat fewer, but larger, meals throughout the day. Many mistakenly believe that “healthy” beverages include fruit juices and sports-type drinks. Removing these completely can achieve better glycemic control. Consuming these drinks usually results from inability to read a nutrition label, so it is helpful to discuss how to read and determine the following: serving size, total carbohydrates, total number of calories, amount of sugar, and alternative forms of sugar. Helping the patient switch solely to drinks with artificial sweeteners—and optimally, water—often produces quick results. Also, patients should consume smaller, more frequent meals at specific times throughout the day. An optimal number of meals would be four to six small meals, eliminating snacks altogether. The patient should also check postprandial blood glucose levels before and after changing to a four to six small meal per day regimen to learn the effect of certain foods on glycemic control.9,10

Simple carbohydrate counting may also be effective. The patient could be counseled that women need 45–60 g of carbohydrate (or 3 to 4 choices, as 1 carbohydrate choice = 15 g carbohydrate) at each of three meals and 15 g (1 choice) for snacks. Men need 60–75 g (4 to 5 choices) at each of three meals and 15–30 g (1 to 2 choices) for snacks. Patients should calculate the total carbohydrate per serving size and divide that total number by 15. The resulting number is the number of carbohydrate choices in that particular serving size of the food item. However, these carbohydrate choice recommendations are for the average patient. If the patient is consuming many more daily carbohydrate choices at baseline, the pharmacist should recommend “small steps” to achieve the goals, as recommended above.9,10

Other helpful information for MNT includes having the patient keep up with all meals and portion sizes for a week. Then, the pharmacist can discuss how to make better food choices throughout the day. Using a sample meal plan and providing a food list for that meal plan is also effective. Other discussions could include the plate method of planning meals and estimating portion sizes based on the palm, fist, thumb, and thumb tip. The plate method involves limiting a quarter of the plate to each of the following: fruit, nonstarchy vegetables, lean meat, and starches.13 Portion sizes can be estimated according to the following: the palm equals three ounces of cooked meat, the fist equals 1 cup (30 g) of carbohydrates, the thumb equals one tablespoon or serving of salad dressing or reduced-fat mayonnaise, and the thumb tip is about one teaspoon or serving of margarine. The ADA Web site (www.diabetes.org) provides other useful tips regarding MNT.14

If time allows, the MNT discussion should be coupled with tips on increasing physical activities and exercise. Patients with diabetes should spend at least 150 minutes per week engaging in aerobic exercise of moderate intensity, designed to increase the heart rate to 50–75% of the maximum. If patients spent 30 minutes per day for 5 days a week, they would be able to adhere to this recommendation. Ideally, no more than two consecutive days should pass without increased activity in this manner. This standard recommendation, in practice, must be highly individualized to implement. The most important thing to remember is for the patient to start implementing small increments of exercise into a daily routine to work toward this goal. Many patients become frustrated with this recommendation. They feel that they are “active,” but upon further questioning the pharmacist may discover that the activity is not aerobic. Instead, patients consider “puttering in the garden” as being active. It should be emphasized that the 30 minutes (alternatively, exercise can be two separate 15-minute activities) should be a continuous activity with the goal of increasing the resting heart rate to at least half of its maximum rate. Also, many patients (e.g., patients with arthritis) have limitations for weight-bearing exercise. These patients should be encouraged to participate in activities such as swimming or swim aerobics. Even walking in place for 30 minutes can be helpful for some patients. Patients should be encouraged at each visit to increase their level of activity in order to realistically achieve their weight loss goal.9,10

Other Counseling Points for Initial Visits

In addition to the other topics of discussion, the pharmacist should be prepared to discuss the following:

![]() Proper education on medications

Proper education on medications

![]() Insulin injection technique and proper storage (if applicable)

Insulin injection technique and proper storage (if applicable)

![]() Diabetes self-management education (DSME)

Diabetes self-management education (DSME)

![]() Sick day management

Sick day management

![]() Foot care

Foot care

![]() Importance of adherence

Importance of adherence

Medication Therapy and Principles of Management

The overall aims for MTM of diabetes are to achieve individualized A1C goals and to prevent microvascular complications of diabetes while avoiding hypoglycemia, blood glucose instability, and significant quality-of-life reduction. As tools to accomplish these aims, several new classes of medications have received approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of diabetes over the past decade. Treatment guidelines and principles of medication management have changed in response to new studies and medication approvals. Although guidelines by several organizations recently have been published, all agree that treatment for patients with diabetes must be individualized.15–21

General Principles of Using Oral Agents

As stated earlier, reduction in A1C to <7% has been associated with significant reductions in microvascular complications and, if achieved early in the course of type 2 diabetes, possibly macrovascular complications as well. Thus, a main principle to consider prior to starting therapy is the baseline A1C. Patients with a high baseline A1C are not likely to achieve sufficient A1C reduction with oral therapy—even with dual or triple combination therapy.9 A recent position statement from the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) suggests that insulin therapy should be started if the baseline A1C is ≥10%. If baseline A1C is below this level, it may be reasonable to begin oral therapy according to this position statement.22 Alternatively, the most recent guideline from the AACE suggests that if the patient is symptomatic for hyperglycemia and the A1C is >9%, insulin could be started.

Most guidelines suggest that metformin, a biguanide, should be initiated for treatment of type 2 diabetes along with lifestyle interventions at the time of diagnosis. Metformin should be initiated unless (1) contraindications exist, (2) the A1C level indicates the need for insulin (at which time both insulin and metformin could be started), or (3) the A1C level is very close to goal (within 0.5% of goal) at the time of diagnosis and the patient is motivated to make appropriate lifestyle interventions. Metformin reduces hepatic glucose production, is weight neutral, and does not increase the risk of hypoglycemia when used as monotherapy. It is a cost-effective agent for glycemic control and has been shown in the UKPDS to reduce mortality in obese patients. However, it is associated with dose limiting gastrointestinal side effects and should be avoided in any patient at risk of lactic acidosis (serum creatinine ≥1.4 ng/dL for females and ≥1.5 ng/dL for male, or heart failure exacerbation), patients receiving contrast dyes, or those with significant hepatic dysfunction. Most patients can tolerate the gastrointestinal side effects if they take metformin with meals, and the dose is started at 500 mg once or twice daily. After a few weeks, it should be titrated up to the maximum effective dose, which is 1000 mg twice daily, for the maximum benefit of lowering A1C.9,10,11

Advancing to Dual Therapy

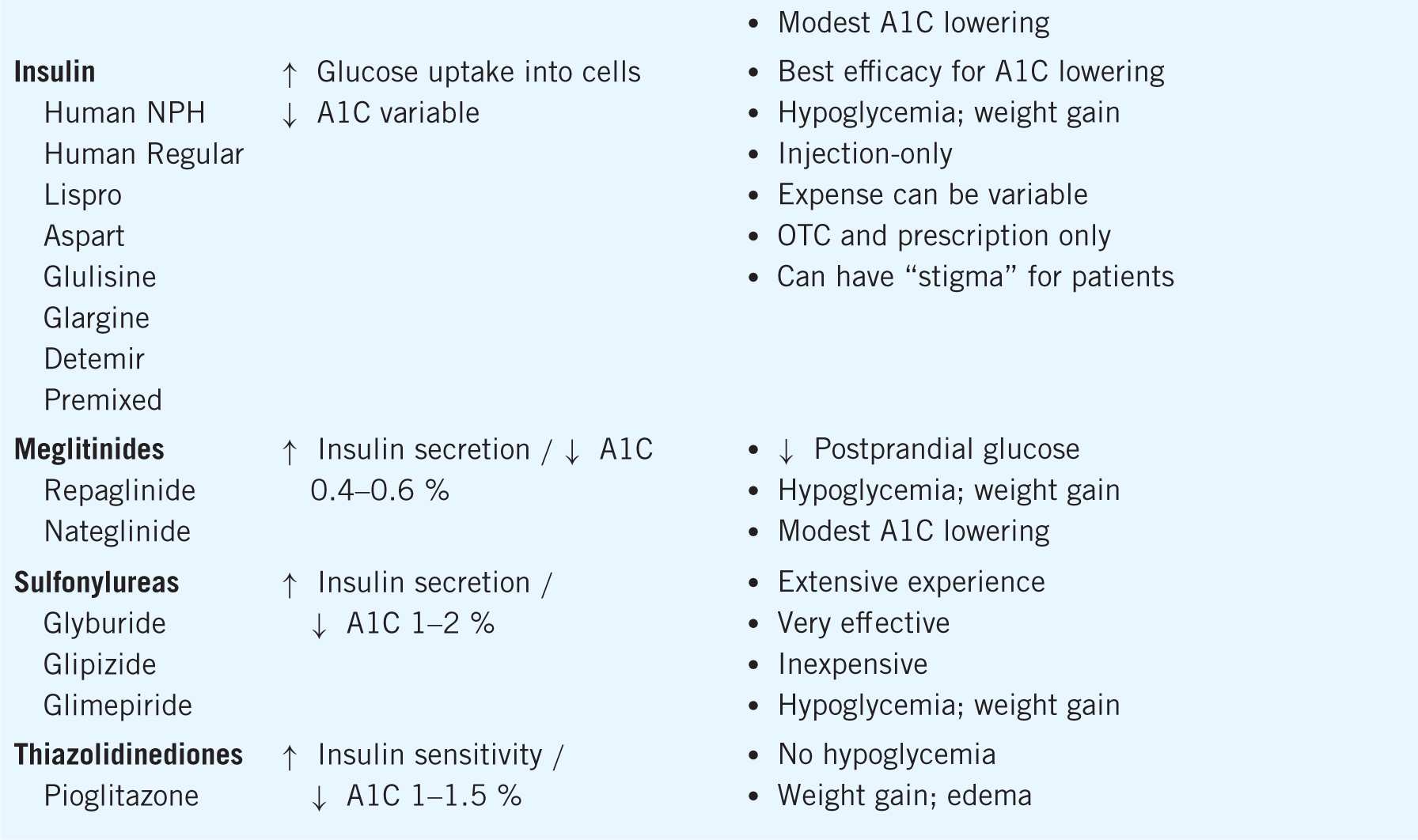

If monotherapy with the maximized dose of metformin fails to achieve the desired A1C goal within about 3 months, the following actions can be taken: (1) add a second oral agent, (2) add a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist (injection), or (3) add basal insulin. However, the choice of next oral agent to add with metformin is unclear. The choice should be individualized according to efficacy in A1C lowering, unique benefits, dosing frequency, side effect profiles, and cost. In general, the A1C lowering capacity is greatest for metformin and sulfonylureas (average 1–2%), next greatest for GLP-1 agonists and thiazolidinediones (average 1–1.5%), and least for meglitinides, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs), and colesevelam (average 0.5–1%). The mechanisms of action, A1C lowering, and advantages and disadvantages of each diabetes medication can be found in Table 11–1.9,10,11

Table 11–1. Medications for Treatment of Diabetes

However, in context of adding on any of the above oral agents to metformin, the efficacy of lowering the A1C further is only about 1%. If the patient is a “nonresponder” to an adequate trial of the additional agent (no clinically meaningful reduction in A1C), that agent should be discontinued and an alternative agent added to metformin. Achieving optimal glycemic control should be the focus to alleviate the risk of complications, and therapy should be advanced methodically to achieve this goal.9,10,11

Advancing to Triple Therapy

Some studies have demonstrated efficacy of achieving glycemic control when a third oral agent is added to two-medication therapy. The most likely patient would be one who needs a 1% or less reduction in A1C to meet glycemic goals and does not wish to start insulin. Patients should be counseled thoroughly regarding possible side effects and likelihood of achieving target goals. As discussed with dual therapy, patients should not be allowed to linger with an extended trial of triple combination therapy if efficacy is not achieved within a reasonable time frame. When considering the progression from dual oral therapy, most patients should be transitioned to insulin therapy if the degree of hyperglycemia remains elevated with a two-drug regimen (e.g., A1C ≥8.5%, for those with a goal of <7%).9,10,11

Transitioning to Insulin

Although many patients are reluctant to start insulin therapy, thorough counseling, encouragement, support, and even use of motivational interviewing tools can assist in the transition. A basal insulin is usually begun at a low dose, such as 0.1–0.2 units per kg per day. For example, glargine (10 units) is typically started for many patients. Larger amounts of basal insulin (0.3–0.4 units per kg per day) are reasonable starting doses for patients who have very poor glycemic control.

At this time, oral regimens should be evaluated for continuation with insulin initiation. Continuing metformin is usually reasonable and effective for most patients. However, oral agents that enhance insulin secretion (i.e., sulfonylureas and meglitinides) are usually stopped, or the dose decreased, to eliminate increased risk of hypoglycemia. If postprandial blood glucose levels are elevated, bolus insulin (or a GLP-1 agonist as an alternative) could be started prior to meals. The class of TZDs could increase weight gain in combination with insulin and are usually avoided when starting injections as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree