While these domains and subdomains provided categories on which to focus educational activities and assessment methods, they lacked a developmental perspective necessary to encompass the timeframe of the TIME initiative, spanning from high school graduation to medical school graduation. The task force adapted developmental descriptions from the professionalism competencies of the Pediatrics Milestone Project, which include five levels of professional identity milestones.9 The first three levels are relevant to learners in the TIME initiative:

- Phase I:

Transition – participates as an interested but passive observer

- Phase II:

Early developing professional identity – appreciates the professional role but does not take primary responsibility

- Phase III:

Developed professional identity – understands the professional role with a genuine sense of duty and responsibility

The fourth and fifth phases (mature professional identity and broadened professional identity) are relevant to graduate medical education and professional practice, indicating that PIF continues to evolve following medical school graduation.10

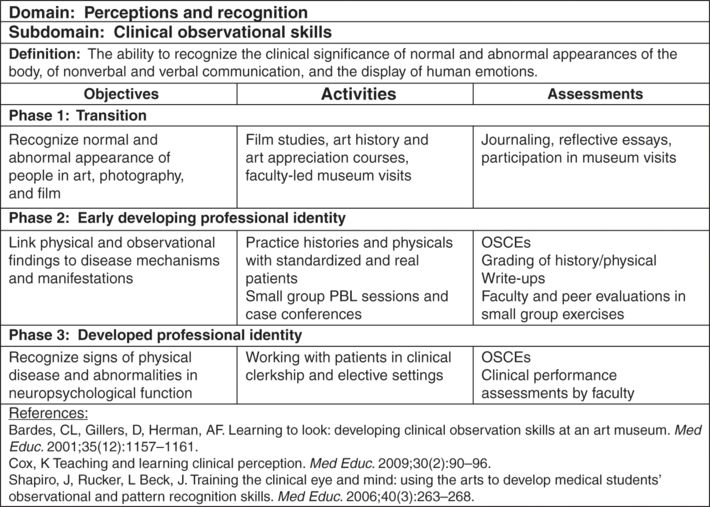

Incorporating this longitudinal trajectory, the task force constructed a framework of educational activities and assessment strategies for each domain and sub-domain across the three developmental phases. The framework also includes phase-specific objectives, definitions, background references, and resources for educators and learners (Figure 16.2). To enhance the utility of the framework, the task force worked with technology experts to convert the contents into a searchable web-based tool configurable by domain, subdomain, phase, and key word.3,8

While the framework does not incorporate competency-based education, it does map many of the subdomains to the TIME initiative competencies. The PIF framework serves as a longitudinal thread alongside the TIME competencies, as advocated by Jarvis-Selinger.11 This parallel construction is particularly important because the institutions in the TIME pilot program partnerships vary significantly in their individual academic curricula and approaches. The PIF framework provides a menu of options for each subdomain along the three-phase continuum, allowing individual institutions to incorporate the most appropriate, useful, and efficient aspects as they focus on PIF within their curricula.

Rationale for recommended methods to promote professional identity formation

Convergent with the writings of others, four guiding principles informed the development of recommendations for educational activities to foster and support PIF.7,11,12,25 First, activities targeting PIF should encompass existing pedagogical strategies when possible and have an explicit focus on PIF. Second, activities should promote a way of being, not only a way of doing. Third, activities should target psychological growth at the individual level and socialization at the collective level. Lastly, the curricular approach should be longitudinal and build increasing responsibility for patient care.

Educators will recognize most of the activities listed on the task force framework website in support of each phase of PIF.3 Grounding the framework and its phases in existing activities provided concrete references to the domains, drawing everyday relevance to potentially elusive identity constructs. This approach facilitated application of the PIF framework to curricular and extracurricular development. In addition to being familiar and integral to medical education, many activities span multiple domains and subdomains in the framework, allowing for efficient integration of students’ PIF with existing formal and informal curricula.13–15 The framework includes extracurricular activities in recognition that identity formation is a complex process encompassing learning in the formal, informal, and hidden curricula. The recommended activities utilize existing pedagogical strategies with an explicit emphasis on PIF, thus facilitating integration with other components of the curricula.

The recommended activities target deep personal transformation associated with identity change. The progression of activities includes adopting professional behaviors and practicing being in the role of physician while the underlying principles are internalized. Changes in behavior can influence attitudes as well as the reverse.16 Instruction regarding professionalism is an essential and logical starting point and can be integrated with instruction regarding humanism.

The progression of PIF activities from transition to developed phases complements students’ progression from the curious observer exploring professional opportunities to the engaged learner internalizing the knowledge and values of the profession consistent with other frameworks for personal and professional development.17–20 The PIF phases of transition, early developing, and developed identities may require changes in attitudes, habits, and relationships. Psychological growth and professional socialization must be fostered in ways that emphasize their comparable importance to the mastery of scientific content and clinical skills.

Educational activities fostering the deep transformation associated with PIF should be longitudinal and cumulative in nature and include a clear focus on the patient as PIF occurs primarily in the context of patient care. The framework recommends engagement in authentic, situated learning early in the educational process. Transformation through PIF experiences arises from feedback and self-reflection, leading to insight into the potential congruence of personal and professional identities.22–25 The PIF experiences listed in the framework derive from the practices, standards, and ethics of medicine as a science, an art, a profession, and a culture.25 For PIF experiences to be relevant, students’ work should relate closely to patients and patient care.24,26 More broadly stated, PIF experiences appear grounded in the human condition, human interactions, humanism, and, ultimately, humanity.

Recommended pedagogic strategies

Reflection

For experiences to inform students’ core values, self-reflection, especially regarding dissonances, provides necessary respite to discern the personal relevance.22,27–32 Reflective writing as well as discussions of books and movies are included in the PIF framework as recommended activities. Both introspection and consideration of the reflections of others can foster personal growth.33–35 Reflective writing may take the form of assigned essays with specific topics or routine personal journaling regarding the impact of experiences on personal growth. Recommended topics for reflection include critical incidents, clinical encounters, and ethical dilemmas.

Clinical experiences and clinical skills training

Patient-centered experiences can enhance students’ PIF.36 In the context of the framework described above, student experiences provide increasing proximity to patient care, for the patient encounter represents the epicenter of physician practice, as described by Verghese.37 A physician must also effectively present explanations to patients and peers to effect high quality, compassionate, and safe patient care.38–41 The necessary communication skills develop through a variety of simulated and authentic interactions in formal and informal curricula.26,42,43 Early clinical experiences may occur through shadowing, volunteering, and longitudinal clerkship experiences to support developing PIF.44

Experiences of the profession

Professional standards, statutes, and credentialing regulate a physician’s practice. PIF experiences relative to this realm enable students to gain insight into the official parameters of practice.45–47 Medical student education in professionalism, including e-professionalism, remains a tenet of physicianhood.48 Brody and Doukas point out that professionalism education for medical students falls under two precepts: trust-generating promise from physician to patient and application of virtue to practice.49 The Physicianship curriculum at the McGill University Faculty of Medicine provides an exemplar of such education.50 Such experiences may mitigate factors that result in future impairment and disruptive conduct.51–53

Experiences in the arts, history, and wellness

The academic separation of sciences and humanities in medical education arose from historical roots resulting in greater emphasis on scientific equanimity over humanistic practice.54 In the mid twentieth century, the introduction of humanities into American medical education came in response to a growing need to train holistic physicians with broad backgrounds and experiences.54–55 Elective humanities experiences provide medical students with creative, reflective, and safe media to explore the human condition and to hone observational skills as well as metacognitive skills.55–56 Examples of such opportunities include medicine in literature, cinema, history, and arts. Deliberately created to weave mindfulness, humanism, and healing, Remen’s “Healer’s Art” elective allows medical students and faculty to connect their education and practice with their humanity and to develop resilience against professional identity deformation.57–60

Mentoring and advising

Guidance provided by mentors, teachers, and role models, including peers, enables students to consider their personal growth with relative safety24 exerting powerful influence on students’ perception of the profession and the professional61–62 often within the context of the hidden curriculum.25 Opportunities for positive role modeling and mentorship may be established via learning communities and programs, including student organizations, for career exploration and formal advising opportunities.

Additional pedagogies

Learning communities harness the collective expertise, experiences, and energy of students to create and sustain an active culture of education and life on and off campus63 offering longitudinal and regular touchpoints for PIF through experiences that bring together faculty and students.64 Learning communities serve as a tool for teaching and learning professionalism65 and may provide a focus on student career counseling and wellness in synergy with formal curricula.66

Interprofessional experiences positively support students’ individual PIF and may give rise to tension in team dynamics when individuals strongly identify with their profession over the team.67 Strategies to mitigate such tension include awareness of affective conflict emergence, commitment to shared goals, and exploration of shared values.67 Interprofessional experiences focusing on common patient-care goals are effective.67–69 Key ingredients for programmatic success include administrative support, faculty and student commitment, and interprofessional infrastructure.70

Extracurricular opportunities such as summer camps for children with medical conditions, student organizations and government, community service, and global health electives enrich students’ education and better prepare them for practice in a multicultural, interprofessional, and patient-centered environment advancing their PIF through contextual exploration and application.71 Students calibrate their moral compasses and affirm their future role in society through service learning experiences.71 International medical missions and global health experiences immerse medical students in cross-cultural settings that can strengthen and challenge their PIF.72,73

The societal expectation that physicians will serve as leaders has been the subject primarily of informal, extra-, and hidden curricula.74–76 Formal leadership training in the medical curriculum, including dual-degree programs, could more effectively prepare medical students to be positive change agents in the healthcare environment.76–80 Research opportunities for medical students, including quality improvement studies, introduce them to scholarly aspects of the profession, hone their scientific literacy and critical thinking skills,81–82 and can integrate reflection, self-improvement, and mentorship necessary to support PIF.83

Rationale for recommended strategies to assess professional identity formation

The complex nature of PIF presents formidable challenges to the assessment of students. Contemporary understanding of the process as multifaceted, nonlinear, and largely noncognitive led to careful examination of the assumptions and frameworks the task force employed to develop strategies for assessment.

The first consideration was the purpose of assessing PIF. The approach of the task force was to construct assessments for learning rather than assessments of learning.84 Assessment for development (formative) identifies current status of students for the purpose of planning a future course of action. Assessment of development (summative) identifies current status in order to identify progress from a past position or to compare to standards. Different domains or subdomains may develop at different rates as a result of experience. In addition, new identities arise cyclically throughout the educational process, e.g., from student observer of care to student provider of care to upper-level-student role modeling provision of care. The lack of an expectation of common trajectories or benchmarks renders an achievement paradigm associated with summative assessment rarely applicable. The process of PIF currently has insufficient explication to allow standard setting.8 Assessments of PIF are information to be utilized by learners, mentors, and advisors to select and shape next steps in students’ personal and professional growth and learning. The recommendation of the task force to the TIME partnerships is that assessment be designed and implemented formatively.

A second broad principle guiding the strategies for assessment of PIF is that such assessment should be programmatic by design.85,86 This approach strengthens the validity of assessment by employing multiple methods from multiple perspectives over multiple occasions. Assessments specifically targeting development within subdomains are important building blocks to a broader view of PIF. No single assessment sufficiently captures the breadth and depth of PIF. For example, within a given time period, students might engage in reflective writing providing insight about their service orientation; participate in an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in which the standardized patients evaluate their professionalism; and be evaluated by preceptors on cultural competence in their patient encounters. Such a combination of assessments would provide a rich descriptive quilt of students’ development within the attitudes domain in the framework. Careful planning or blueprinting facilitates programmatic assessment that encompasses the complexity of PIF. The task force recommends that responsibility for planning programmatic assessment be explicitly incorporated into curriculum design for PIF. Portfolios are also recommended for capturing the combined assessments and providing a longitudinal perspective.

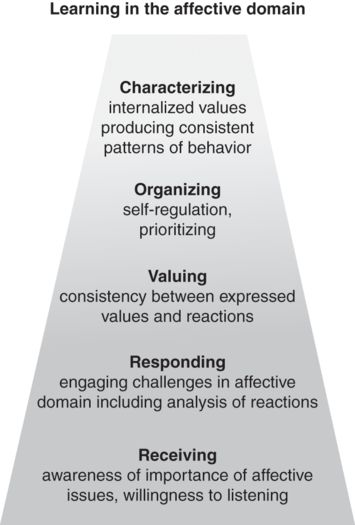

The third guiding principle of the task force in approaching assessment of PIF was that it is a form of learning primarily in the affective domain as identified in Bloom’s taxonomy of affective learning, rather than the more commonly used cognitive taxonomy.87 Bloom’s levels of learning in the affective domain, as outlined in Figure 16.3, provide a useful framework for planning formative, contextual assessment of the domains and subdomains of PIF.

Assessment of professional identity formation development may consider levels attained in Bloom’s taxonomy87

Students in the transition and early developing identity phases may be expected to exhibit an awareness of the importance of the values and habits of the profession. Through their continued PIF development, students would likely be able to respond critically to cases or literary representations of physicians facing challenging situations. Eventually, students would develop a consistency between their perception of who a physician should be and the reality of who they actually are. For example, students may believe that physicians should be empathic and, therefore, practice empathy with patients and colleagues. Eventually, they are able to self-regulate in ways that allow them to behave consistently with their physicianhood in the face of competing emotions or values. At this level, students would demonstrate empathy even as they process feelings such as anger or dislike that might otherwise be directed at the patient. Eventually students achieve a level of consistency across domains to serve as role models for the attitudes, habits, and values fundamental to being humanistic physicians.

An assessment system for PIF requires sufficient flexibility to accommodate development at different rates across subdomains. Students may respond to a sense of duty and value cultural competency in their acceptance of peers with different backgrounds, thus attaining different levels on Bloom’s affective taxonomy. Considering the progression of development in Figure 16.3 helps move assessments away from dichotomous approaches toward more complex strategies examining the quality of development in a domain or subdomain. Such information can then become the focus of mentoring sessions or personal growth plans.

Because PIF develops within the context of learning and practicing, assessment also needs to be contextual. Therefore the task force recommended, where possible, to embed assessment of identity formation within existing assessments, adding elements specifically targeting PIF. Such opportunities are present in the application of reflective writing, OSCEs, faculty evaluations, peer evaluations, surveys, and portfolios. Reflective writing is a curricular activity thought to deepen the learning experience and promote PIF.33–35 Adding an assessment element may range from having the written products as a topic of discussion with mentors to having students answer essay questions about what they need to facilitate their growth into the next phase of development. OSCEs and faculty evaluations as well as peer evaluations provide external formative touchpoints for learners. Adaptation of existing assessments may include adding questions regarding perceived development in a specific subdomain or more broadly about areas of strength or challenge in developing identity. Similarly, medical students regularly complete surveys for a variety of purposes. Inclusion of questions about professional identity in course evaluations or standardized survey instruments targeting specific subdomains can yield rich PIF information for learners and mentors. Portfolios designed to capture evidence of competency attainment can include a section for information about identity development. The aggregation of information into a portfolio would provide a longitudinal perspective allowing for a broader view of students’ developmental trajectory not readily available from more narrow or discrete pieces of information.

The triangulated strategies described thus far constitute an overall approach to the assessment of PIF, measuring multiple aspects from multiple perspectives at multiple points in time. Development of assessment blueprints, at least at the pilot program partnership level, was endorsed by the task force as a strategy to ensure that all domains are assessed across time. This raises the question of whether there is a gestalt to PIF that will be missed by such a granular approach. The task force encouraged medical educators at all partnerships to explore opportunities for global assessment, having found no well-developed approaches for global assessment of professional identity to recommend prior to implementation of the TIME initiative.

Implementation of the recommendations

Promotion of professional identity formation

The TIME initiative institutions have incorporated multiple methods to enhance the development of professional identity, based on the rationale previously discussed. These methods include early, authentic clinical and immersion experiences, reflection, community service learning, learning communities, and mentoring and advising, in addition to structured courses incorporating foundational concepts in ethics, humanities, and professionalism. Undergraduate and medical school campuses of the four pilot program partnerships incorporate these strategies for different levels of students in various ways based on local curricula, resources, and preferences. We will summarize several examples in which these strategies have been integrated into curricula at undergraduate and medical school campuses.

Summer experiences

At many undergraduate campuses, students enter the TIME initiative in the summer immediately following high school graduation. During the initial summer, students are introduced to the program, expectations, active learning modalities, competency-based education, and the concept of PIF. Subsequent summer sessions include community service learning, clinical skills development, preceptorships with community practitioners, global health immersion experiences, and travel to medical school campuses. These diverse experiences integrate reflection, role modeling, mentorship, teamwork, and authentic clinical encounters, all of which are reinforced throughout their fall and spring semester courses and extracurricular activities, in part by medical school faculty who conduct workshops at the undergraduate campuses.

Longitudinal educational patient-centered medical home

The implementation of a longitudinal clinical experience in one medical school is characterized as an educational home for the students. Students begin this experience at matriculation to medical school and have longitudinal experiences with and increasing responsibility for a panel of patients. Students also have longitudinal membership in the interprofessional team and access to faculty and peer mentors. Weekly team meetings include review of cases and relevant clinical topics, as well as opportunities for reflection and presentations related to self-care and communication. Students complete reflective writings on a regular basis, with feedback from faculty mentors. These complex and challenging clinical experiences provide rich opportunities for reflection, development of clinical skills, role modeling, and mentoring.

Doctoring courses

The medical school campuses include doctoring courses of various designs. At one school, students participate in doctoring courses across all four years. These courses, taught mainly in small groups by clinical faculty, incorporate clinical skills development, simulated and real clinical encounters, ethics, professionalism, medical humanities, theater, reflective writing and discussions, and mentoring and advising. Students also discuss topics such as self-care, burnout, impairment, professional dilemmas, awe in medicine, career options, and humanism.

These activities and content topics are very pertinent to the development of professional identity and are included in the PIF framework.

Courses at another pilot partnership medical school and some undergraduate campuses use The Brewsters: An Interactive Adventure in Ethics for the Health Professions.88 As students work through this fictional story, they select characters and make decisions in ethically and professionally charged situations, while incorporating the foundations of professionalism and ethics. Other programs incorporate art observation experiences or creative expressions projects. Integrated into these various activities are multiple opportunities for reflection and feedback.

Student learning communities

Several UT System medical schools have developed learning communities. At one school, all students are placed into learning communities on entry into medical school. These groupings are utilized for small-group class assignments during the first two years. The learning communities promote community service learning, socialization, social support, role modeling, and faculty and peer mentoring.65 Some undergraduate campuses have also developed learning communities for their TIME students, promoting teamwork, mentoring, and social support.

Scholarly concentrations

Medical school curricula routinely provide students with opportunities for concentrated study in an area of interest. These are integrated over the duration of medical school and include elective courses and extracurricular experiences. They include learning communities, meetings of faculty and students with similar interests, opportunities for mentoring, and professional socialization. Some areas of concentration are specialty-related, e.g., aerospace medicine or geriatrics. Others allow students to deepen their exploration of subjects that receive minimal attention within traditional medical curricula, e.g., medical humanities or translational research. A third category of concentrations relates to cultivating the values of a competent, humanistic physician. These include programs in global, rural, and bilingual health in which students’ experiences prepare them to address the needs of patients who often experience barriers to healthcare.

At one pilot partnership medical school, a scholarly concentration has been designed and implemented with the explicit purpose of supporting students’ PIF. Small groups of six to eight students and two faculty members meet for dinner throughout medical school. These meetings include reflective discussions of assigned experiences as well as regular written reflections including journaling and essays. The small groups and eight-week preceptorship after the first year of study provide sustained mentoring within a learning community. The first year of the track focuses on personal development topics, e.g., stress management and mindfulness. The second year focuses on being authentic in interactions with others, e.g., experiencing and expressing empathy, cultural understanding, and delivering bad news. In the third and fourth years, these topics are revisited with an emphasis on application in a clinical context. Elements of this cohesive, longitudinal program are being adapted for use with all students.

Extracurricular activities

Students at medical and undergraduate campuses have access to a variety of extracurricular activities that promote PIF. These include clinical shadowing, research projects, student-run free clinics, partnerships with local schools for health education and coaching, faith-based volunteering, and community services. These diverse experiences provide rich opportunities for personal and professional growth.

Assessment of professional identity formation

Assessment activities vary widely across pilot program partnerships. Integration into other assessment activities has been challenging on the undergraduate campuses where there is little to no precedent for assessing professionalism or identity development. Appropriately for learners in the initial phases of identity development, most assessments focus on the receiving and responding levels of Bloom’s hierarchy of affective learning.

One common activity among partnerships is reflective writing about movies or literature, highlighting the affective qualities that impact the success of physicians, or writing about the emotional impact of early clinical experiences, such as volunteering with health providers in resource-limited regions. Through these activities, mentors are able to assess the extent to which students develop an awareness of the importance of affective issues in physician identity and are willing to analyze their own affective reactions. For many students in this phase, learning the science necessary for entry into medical school overshadows the importance of affective development. Feedback on required reflections provides an important mechanism for introducing students to the importance and need for continuing development.89,90 Integration of reflective writing is both a curricular strategy for developing reflective practice and an assessment strategy for assessing students’ ability to critically reflect and their development in other content-dependent domains. For example, students’ reflections on volunteer experiences provide insight about students’ reflective capacity and about the nature of the volunteering activities and their contribution to students’ PIF.

All campuses have developed some mechanism for identifying lapses in professionalism and providing feedback to students as issues arise. This type of assessment increases student awareness of the importance of affective issues and helps them engage in the process of identifying and addressing challenges. It is necessary to identify student lapses in professional development in order to identify students’ needs for support and opportunities for remediation.91 It may be challenging to maintain a culture of positive, constructive feedback necessary for growth if this is the primary form of assessment.

Another common strategy is the inclusion of PIF in end-of-semester or end-of-year evaluation meetings. These meetings between students and mentors or advisors include consideration of both competency achievement and PIF. During undergraduate years, the discussion around PIF at these meetings centers on issues of self-direction, self-assessment, ability to use feedback, and accepting responsibility for meeting obligations.

Peer evaluation has been identified in some partnerships as a transformational assessment strategy. Students who are trained to give specific, constructive feedback can communicate effectively with peers about their perceptions of one another’s development in domains of interest. Students could discern whether and how the habits of their peers are those that would contribute to the effectiveness of being a physician, e.g., critical thinking, self-care, or self-directed learning. Such items can be included alongside more traditional evaluations of team members, e.g., punctuality, cooperation, or listening skills. For example, one summer course uses a team professionalism contract in which student teams agree to abide by professionalism principles in the course. Students are held accountable for the professional conduct and actions of the entire team. Thus, students learn to observe peer behavior, provide feedback, and devise corrective strategies. This moves the learning from the responding level of Bloom’s affective taxonomy, in which students would analyze cases presented to the class, into the valuing level, in which they examine their own and others’ behavior for consistency with clearly articulated values.

Several partnerships use individual professionalism contracts. These have been used as learning strategies as well as assessment tools. These contracts provide clear expectations, structure experiential learning of professional habits, and serve as a basis for self-assessment to be compared with the perspectives of other assessments as a topic for discussions with mentors, advisors, and peers.

Surveys designed specifically for students in the TIME program as well as standardized instruments have been used as part of programmatic assessment. One partnership has adapted a professionalism self-assessment originally designed for students in physician-assistant training. Standardized instruments of empathy that we have used include the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) and the Jefferson Scale of Empathy.92,93

Data from numerous sources appear in portfolios and can be considered as indicative of PIF. Cognitive assessments of the fundamentals of professionalism and ethics also serve as formative assessments of development when used as the basis for discussion of the implications for the process of becoming a physician. Evaluations and letters from clinical faculty whom students shadow and supervisors at sites where students volunteer often contain comments about responsibility, professionalism, and opportunities for addressing additional domains and subdomains of the PIF framework.

Management of assessment information provides significant additional challenges. The need for longitudinal assessment that reflects growth over time requires accumulation and coordination of assessment data. Some partnerships maintain databases dedicated to track all PIF information and feedback for students. Others utilize portfolios to compile evidence of PIF in addition to targeting evidence of competency-based achievement. Integrated approaches of combining curricular experiences and formative assessment, e.g., reflection, professionalism contracts, and self-assessments, including aspects of the learner’s identity development, ease the management and implementation burdens. At the UT System level, an effort is underway to develop a common database format to serve as both portfolio and data repository.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree