Overview

Overview

“Dermatitis” is a nonspecific term describing numerous dermatologic conditions that are generally characterized by erythema. The terms “eczema” and “dermatitis” are used interchangeably to describe a group of inflammatory skin disorders of unknown etiology. Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, relapsing skin disorder that typically begins during infancy or early childhood and often lasts into adulthood. Atopy is a genetically predisposed tendency to exaggerated skin and mucosal reactivity in response to environmental stimuli. Atopic dermatitis is part of the “atopic triad,” along with asthma and allergic rhinitis; asthma and allergic rhinitis occur in 30%–80% of cases of atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis often is the initial clinical manifestation of an allergic disease.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

- Atopic dermatitis is considered the most common dermatologic condition of children, with >5% of children affected by age 6 months.

- Atopic dermatitis is more common in boys, whites, higher socioeconomic classes, and urban areas.

- The incidence of atopic dermatitis may be increasing, from 3% of children after World War II to 10%–15% today. This may be due in part to increased exposure to pollutants, irritants, and indoor allergens (particularly house-dust mites), as well as a decline in breast-feeding.

- Atopic dermatitis persists or recurs in about 60% of affected individuals.

Etiology

Etiology

- Atopic dermatitis has a genetic basis, but its expression is modified by a broad spectrum of exogenous manifestations.

- There is a family history of atopy in the majority (70%) of cases of atopic dermatitis.

- Common exacerbating factors for atopic dermatitis include foods, soaps, detergents, fragrances, chemicals, temperature changes, dust, pollens, certain bacteria, and emotional changes.

- Compared with the general population, patients with atopic dermatitis may be more sensitive to irritants.

- Allergens—typically plant or animal proteins from food, pollens, or pets—may aggravate atopic dermatitis.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

- Atopic dermatitis is diagnosed according to clinical criteria (see Table 1).

- The primary sign of atopic dermatitis is intense pruritic papules (solid, circumscribed, elevated lesions <1 cm in diameter) and vesicles (sharply circumscribed, elevated lesions containing fluid).

- Pruritus is the hallmark symptom of atopic dermatitis.

- Atopic dermatitis sometimes is referred to as “the itch that rashes.”

- Scratching and lichenification (increased epidermal markings) can produce a vicious cycle and lead to excoriation (abrasion of the epidermis by trauma).

- Atopic dermatitis sometimes is referred to as “the itch that rashes.”

- The areas commonly affected depend on the patient’s age (see Table 2). Lesions are typically symmetric in patients with atopic dermatitis.

- Although atopic dermatitis often appears initially in infancy, it rarely is present at birth. If atopic dermatitis does develop early in life, it typically occurs within the first year (beginning at age 2–3 months) in approximately 80% of the cases.

- Atopic dermatitis initially appears as redness and chapping of the infant’s cheeks, which may continue to affect the face, neck, and trunk.

- At times, this dermatitis may progress to become more generalized, with crusting developing on the forehead and cheeks. Crusts consist of dried exudate containing proteinaceous and cellular debris from erosion or ulceration of primary skin lesions.

- Remission usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 4 years, with recurrences often diminishing in intensity or even disappearing as the child approaches adulthood.

- Atopic dermatitis initially appears as redness and chapping of the infant’s cheeks, which may continue to affect the face, neck, and trunk.

- Patients with atopic dermatitis react more readily and more persistently to pruritic-inducing stimuli.

- Patients with atopic dermatitis often are intolerant of sudden and extreme changes in temperature and humidity.

- High temperature may enhance perspiration, leading to increased itching.

- Low humidity, often found in heated buildings during the winter, dries the skin and increases itching.

- High temperature may enhance perspiration, leading to increased itching.

TABLE 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis

An itchy skin condition, plus three or more of the following criteria:

Onset at <2 years of age

Onset at <2 years of age

History of skin crease involvement (including cheeks in children <10 years of age)

History of skin crease involvement (including cheeks in children <10 years of age)

History of generally dry skin

History of generally dry skin

Personal history of other atopic disease (or history of any atopic disease in first-degree relative in children <4 years of age)

Personal history of other atopic disease (or history of any atopic disease in first-degree relative in children <4 years of age)

Visible flexural dermatitis (or dermatitis of cheeks/forehead and other outer limbs in children <4 years of age)

Visible flexural dermatitis (or dermatitis of cheeks/forehead and other outer limbs in children <4 years of age)

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Atopic Dermatitis by Age

Age | Location | Signs |

2 months | Chest, face | Red, raised vesicles; dry skin; oozing |

2 years | Scalp, neck, and extensor surface of extremities | Less acute lesions; edema; erythema |

2–4 years | Neck, wrist, elbow, knee | Dry, thickened plaques; hyperpigmentation |

12–20 years | Flexors, hands | Dry, thickened plaques; hyperpigmentation |

Complications

Complications

- Secondary or associated cutaneous infections (especially bacterial) can be common and difficult to prevent. Infections present as yellowish crusting of the eczematous lesions.

Treatment

Treatment

- Although atopic dermatitis cannot be cured, most patients’ symptoms can be managed satisfactorily.

- Patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis usually are candidates for self-treatment with a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies.

- Self-treatment is directed at stopping the itch–scratch cycle, maintaining skin hydration, avoiding or minimizing factors that trigger or aggravate the disorder, and preventing secondary infections.

- Successful treatment of atopic dermatitis requires a systematic, multipronged approach that incorporates (1) skin hydration; (2) the identification and elimination of flare factors such as irritants, allergens, infectious agents, and emotional stressors; and (3) the use of topical and sometimes systemic therapy.

General Treatment Measures

General Treatment Measures

- Errors in bathing and moisturizing are by far the most common factors in persistent atopic dermatitis.

- The stratum corneum in patients with atopic dermatitis contains less moisture than that of normal skin.

- To avoid dehydration, patients should bathe or shower for only 3–5 minutes using fragrance-free bath oils. Some commercially available bath oils include colloidal oatmeal in an attempt to provide better relief of itching.

- The preferred frequency of bathing or showering is every other day (to minimize removal of natural oils), with tepid rather than hot water. The water should not be more than 3°F above body temperature.

- Whenever possible, patients should substitute sponge baths for full-body bathing.

- Common bar soaps often are too drying and irritating for patients with atopic dermatitis. Mild nonsoap cleansers (e.g., Cetaphil) are recommended.

- After bathing or showering, the skin should be allowed to air dry or patted dry gently, leaving beads of moisture. A fragrance-free moisturizer should be applied within 3 minutes while the skin is still damp to trap the moisture.

- Patients often benefit from reapplying moisturizers liberally three to four times daily, at least to the most affected areas.

- The stratum corneum in patients with atopic dermatitis contains less moisture than that of normal skin.

- Excessively dry areas of skin may be covered with a lubricating ointment (e.g., petrolatum, Absorbase, or Aquaphor). However, sweating after the application of heavy ointments may add to the propensity for itching.

- Patients should be instructed to rub a very small amount of product into the affected area.

- Adjunctive measures may be used to minimize scratching and the damage it produces.

- Fingernails should be kept short, smooth, and clean.

- Because scratching may increase at night, even while the patient is sleeping, wearing cotton gloves or socks on the hands at night may lessen scratching.

- Fingernails should be kept short, smooth, and clean.

- Patients with atopic dermatitis should minimize their exposure to irritants, allergens, and any other factors known to exacerbate the condition.

- Patients should be encouraged to use hypoallergenic cleansers and cosmetics.

- Patients should avoid wearing tight, occlusive clothing.

- Patients should be encouraged to wear nonirritating fabrics such as cotton and to launder and rinse all new clothing thoroughly with unscented laundry detergent. Fabric softeners are best avoided; if used, liquids are preferred over dryer sheets.

- If possible, patients should remain in moderate temperature settings and moderate relative humidity conditions. Use of humidifiers in dry environments will provide some benefit.

- Patients should be encouraged to use hypoallergenic cleansers and cosmetics.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

- Astringents (e.g., aluminum acetate) retard oozing, discharge, or bleeding of dermatitis lesions. When applied as a wet dressing or compress, astringents cool and dry the skin through evaporation; they also cleanse the skin of exudates, crust, and debris.

- Aluminum acetate solution (Burow’s solution) contains approximately 5% aluminum acetate. The solution must be diluted 1:10 to 1:40 with water before use.

- Patients may soak the affected area 15–30 minutes two to four times daily.

- Alternatively, patients may soak clean white compresses (washcloths, cheesecloth, or small towels) in the solution, wring them gently so they are wet but not dripping, and apply them to the affected areas. The dressings should be rewetted and applied every few minutes for 20–30 minutes, four to six times daily.

- Any remaining solution should be discarded and a fresh solution prepared for each application.

- Less expensive alternatives to aluminum acetate include isotonic saline solution (1 teaspoon salt in 2 cups of water), tap water, diluted white vinegar (one-fourth cup per pint of water), and plain water.

- Aluminum acetate solution (Burow’s solution) contains approximately 5% aluminum acetate. The solution must be diluted 1:10 to 1:40 with water before use.

- Urea in concentrations of 10%–30% is mildly keratolytic and increases water uptake in the stratum corneum, giving it a high water-binding capacity. It is considered safe and has been recommended for use on crusted, necrotic tissue.

- Lotion and cream formulations containing urea may be better at helping to remove scales and crusts, whereas urea in emollient ointments (e.g., urea in a hydrophilic ointment base) may be better at rehydrating the skin.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmacologic Therapy

- Hydrocortisone 0.5% or 1% is the primary nonprescription pharmacologic agent used to decrease inflammation and relieve itching associated with atopic dermatitis.

- Hydrocortisone should be applied sparingly to the affected area three or four times a day.

- Hydrocortisone cream is the preferred formulation for most patients with atopic dermatitis.

- An ointment formulation may be useful if a patient’s skin is particularly dry and scaly.

- Hydrocortisone should be applied sparingly to the affected area three or four times a day.

- Excessive scratching can result in open sores that may need to be treated with a topical antibiotic preparation. Use of bacitracin/polymyxin B ointment (Polysporin) may be preferred over bacitracin/polymyxin B/neomycin ointment, given that some patients may be sensitized to neomycin.

- Topical anesthetics can help to relieve itching as well as pain. However, because local anesthetics can cause systemic adverse effects, they should not be used in large quantities or over long periods of time, particularly if the skin is raw or blistered.

- Nonprescription topical anesthetics that appear to be safe and effective are benzocaine, lidocaine, and pramoxine.

- Topical anesthetics may be applied to affected areas three or four times daily, but caution should be used because these agents have a sensitizing effect in a small number of people.

- Nonprescription topical anesthetics that appear to be safe and effective are benzocaine, lidocaine, and pramoxine.

- Counterirritants such as camphor and menthol, in concentrations of 0.5%–1%, are available in (or can be added to) lotions and creams to serve as an inexpensive antipruritic.

- Because itching in atopic dermatitis may be mediated by various endogenous substances (including histamine), topical antihistamines such as diphenhydramine can be effective antipruritics. However, because of their significant sensitizing potential, the Food and Drug Administration does not recommend the topical use of such agents for more than 7 consecutive days, except under the advice and supervision of a primary care provider.

- Oral antihistamines have been used to treat the itching of dermatologic disorders with variable results. Some researchers claim that the antipruritic effect is a result of the sedative effects of first-generation agents; others claim the efficacy is caused by antihistaminic activity, although with a delayed onset of several days. (Consult the “Allergic Rhinitis” chapter for more detailed information about oral antihistamines.)

- Oral antihistamines may facilitate sleep in patients who otherwise might be kept awake by itching.

Complementary Therapy

Complementary Therapy

- Oral preparations containing bifidobacteria or lactobacillus and topical application of rice bran are considered possibly effective at decreasing the severity of atopic dermatitis in some patients.

- Insufficient evidence exists to determine whether products containing grapefruit seed extract, licorice, puncture vine, schizonepeta, or vitamin B12 provide any benefit to patients with atopic dermatitis.

- Products containing evening primrose oil, borage, gamma linolenic acid, zinc, or tea tree oil have failed to demonstrate any benefit in the treatment of atopic dermatitis to date.

Cautions and Contraindications

Cautions and Contraindications

- All children <2 years of age with suspected atopic dermatitis should be referred to a primary care provider or dermatologist for evaluation and treatment.

- Patients should be counseled to seek medical attention promptly when signs of bacterial or viral skin infection such as pustules (circumscribed, elevated lesions <1 cm in diameter containing pus), vesicles (especially exudative or pus-filled), or crusting (dried exudate) are noticed.

- Topical hydrocortisone rarely produces systemic complications because its systemic absorption is relatively minimal (approximately 1%).

- Local adverse effects such as skin atrophy occur rarely with nonprescription concentrations.

- Because response to topical corticosteroids may decrease with continued use owing to tachyphylaxis, intermittent courses of therapy are advised when possible.

- Local adverse effects such as skin atrophy occur rarely with nonprescription concentrations.

- Hydrocortisone ointment should not be used on weeping lesions. All hydrocortisone products should be avoided if the skin is open or cracked.

- Many nonprescription hydrocortisone products also contain aloe. Because aloe is an irritant for some patients with atopic dermatitis, these products should be avoided.

- Bath oils and colloidal oatmeal products can make the tub and floor slippery, creating a potential safety hazard (especially for older patients and children). Placing a rubber mat in the tub and a dry rug or towel on the floor will help prevent falling.

- Petrolatum should not be applied over puncture wounds, infections, or lacerations because its high occlusive ability may lead to maceration and further inflammation.

- Urea preparations can cause stinging, burning, and irritation, particularly on broken skin.

- Patients with a previous history of allergic reactions to lanolin generally should avoid lanolin-containing products. However, products containing refined lanolin generally are less likely to be sensitizing and may even be tolerated by patients with a history of allergic contact reactions to unrefined lanolin.

Clinical Pearls

Clinical Pearls

- When applied as wet compresses, bath oils (1 teaspoon in ¼ cup warm water) help lubricate dry skin and may allow a decrease in the frequency of full-body bathing.

- Patients with atopic dermatitis should avoid sunscreens containing zinc and titanium.

- The role of food allergies in exacerbating atopic dermatitis is unclear. Restricting offending foods, especially in children, creates overwhelming compliance problems, and complete resolution of the condition is unlikely. Therefore, it is probably best to reserve dietary management for patients who have severe symptoms and are unresponsive to other treatments.

Follow-Up

Follow-Up

- Patients with atopic dermatitis should be reevaluated in 7 days.

- A scheduled follow-up visit is preferred because visual assessment is the best method of determining treatment response.

- If a patient’s symptoms have not improved or have worsened (continued or additional itching, redness, scaling, lesions, or tissue breakdown) after 7 days of self-treatment, the patient should see a primary care provider.

Contact Dermatitis

For complete information about this topic, consult Chapter 34, “Contact Dermatitis,” written by Kimberly S. Plake and Patricia L. Darbishire, and published in the Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs, 17th Edition.

This subchapter discusses the following types of contact dermatitis:

- Irritant contact dermatitis

- Allergic contact dermatitis

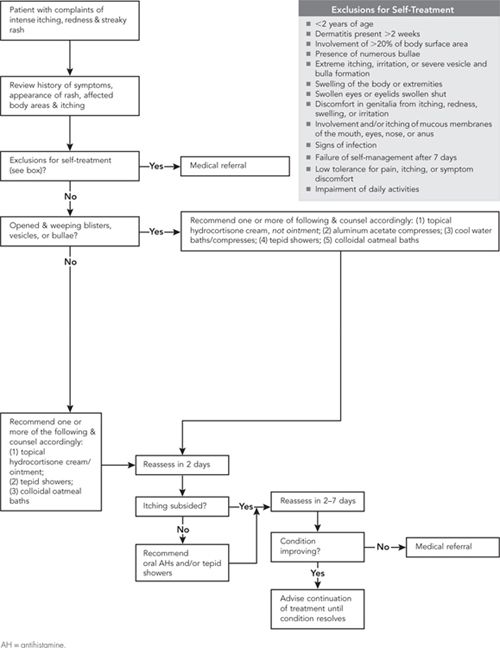

The treatment algorithm pertains to allergic contact dermatitis only.

Self-Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Overview

Overview

Contact dermatitis is a skin condition characterized by redness, itching, burning, stinging, and formation of vesicles and pustules.

Irritant contact dermatitis is an inflammatory reaction of the skin caused by exposure to an irritant (e.g., chemicals, solvents, or detergents). Most cases of irritant contact dermatitis are related to occupational exposures.

Allergic contact dermatitis is an immunologic reaction of the skin caused by exposure to an antigen. Members of the Toxicodendron genus—poison ivy, oak, and sumac—are the principal cause of allergic contact dermatitis in the United States.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

- Irritant contact dermatitis accounts for the majority (80%–90%) of cases of contact dermatitis.

- Allergic contact dermatitis accounts for approximately 10%–20% of cases of contact dermatitis.

Etiology

Etiology

- Most cases of irritant contact dermatitis are job-related, especially in occupations that involve frequent exposure to water or to irritant substances.

- Common irritants associated with contact dermatitis include strong acids and bases, detergents, epoxy resins, ethylene oxide, fiberglass, flour, oils (e.g., lubricating oils), solvents, oxidizing or reducing agents, plasticizers, and wood dust and products.

- Chemical irritants, acids, and alkalis are likely to produce immediate and severe inflammatory reactions. Mild irritants, such as detergents, soaps, and solvents, often require successive exposures before the dermatitis appears.

- Common irritants associated with contact dermatitis include strong acids and bases, detergents, epoxy resins, ethylene oxide, fiberglass, flour, oils (e.g., lubricating oils), solvents, oxidizing or reducing agents, plasticizers, and wood dust and products.

- Poison ivy, oak, and sumac are the most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis in the United States. As much as 80% of the U.S. population is sensitive to urushiol, the oleoresin in poison ivy/oak/sumac that causes the dermatitis.

- The release of urushiol from plants can occur only through damage to some portion of the plant itself. Plants may be damaged directly by individuals who bruise the plant by lying, sitting, kneeling, or stepping on it. Plants also may be damaged indirectly by natural causes (e.g., wind, rain, insects, or animals that eat or damage the plants).

- Urushiol can remain active for long periods of time on inanimate objects. Patients who present with poison ivy dermatitis in midwinter or off-season periods may have recently used an object contaminated with urushiol, such as footwear, clothing, garden or work tools, or sports equipment.

- Although urushiol is not a volatile substance, it has been implicated in dermatitis when plants in the Toxicodendron genus are burned. Urushiol carried by smoke particulates is capable of affecting body surface areas ordinarily viewed as protected (e.g., genitals, buttocks, anus, and lungs).

- The release of urushiol from plants can occur only through damage to some portion of the plant itself. Plants may be damaged directly by individuals who bruise the plant by lying, sitting, kneeling, or stepping on it. Plants also may be damaged indirectly by natural causes (e.g., wind, rain, insects, or animals that eat or damage the plants).

- Metal allergy—most often caused by nickel—is the second most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis (after poison ivy/oak/sumac).

- Latex, fragrances, cosmetics, and skin care products also can cause allergic contact dermatitis.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

See Table 1 for a summary of the key signs, symptoms, and characteristics of irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. Additional information is provided in the following sections.

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Irritant Contact Dermatitis

- Irritant contact dermatitis may appear after a single exposure to an irritant or following multiple exposures to the same agent.

- Irritant contact dermatitis presents primarily as dry or macerated, painful, cracked, inflamed skin.

- Itching, stinging, and burning are common symptoms.

- The dermatitis may crust after a few days.

- Itching, stinging, and burning are common symptoms.

- Irritant contact dermatitis usually develops on exposed or unprotected skin surfaces, especially the face and dorsal surfaces of the hands and arms.

- Resolution of the dermatitis depends on the patient’s ongoing exposure to the irritant.

- If the patient avoids further contact with the irritant, the dermatitis generally resolves in several days.

- In patients exposed to an irritant chronically, the affected areas of skin will remain inflamed, develop fissures and scales, and may become hyperpigmented or hypopigmented. Some patients chronically exposed to irritants recover completely, whereas others improve but continue to have recurrences. Some patients continue to have an inflammatory process comparable to or worse than the original insult.

- If the patient avoids further contact with the irritant, the dermatitis generally resolves in several days.

TABLE 1. Differentiation of Irritant and Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Symptom or Characteristic | Irritant Contact Dermatitis | Allergic Contact Dermatitis |

Mechanism of reaction | Direct tissue damage | Immunologic reaction |

Substance concentration at exposure | Important | Less important |

Appearance of symptoms in relation to exposures | Single or multiple exposures | Delayed |

Location | Primarily hands, wrists, forearms | Anywhere on body that comes in contact with antigen |

Presentation | No clear margins | Clear margins based on contact of offending substance |

Itching | Yes, later | Yes, early |

Stinging, burning | Early | Late or not at all |

Erythema | Yes | Yes |

Vesicles, bullae | Rarely or no | Yes |

Papules | Rarely or no | Yes |

Dermal edema | Yes | Yes |

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- Allergic contact dermatitis represents a two-step process: initial antigen exposure and sensitization (induction phase), followed by a delayed, cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that develops with subsequent exposures to the antigen.

- Initial exposure to urushiol or other antigens usually does not produce dermal symptoms.

- Subsequent exposures to the antigen produce a rash and related symptoms any time between 2 and 48 hours following exposure.

- Initial exposure to urushiol or other antigens usually does not produce dermal symptoms.

- Signs and symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis vary depending on the allergen, site, duration of exposure, and host factors.

- Allergic contact dermatitis usually presents with papules, small vesicles, and sometimes large bullae over inflamed, swollen skin.

- Significant itching is a prominent feature of allergic contact dermatitis.

- Allergic contact dermatitis usually presents with papules, small vesicles, and sometimes large bullae over inflamed, swollen skin.

- A common patient presentation that strongly suggests urushiol exposure is linear streaks of vesicles that correspond to the points of contact with the plant. Specks of black, oxidized urushiol may be apparent on the skin and clothing.

- The initial dermal reaction in urushiol-induced dermatitis is an intense itching of the exposed skin surfaces, followed by erythema. Itching may be more intense in older patients than in younger adults.

- If the urushiol is not washed from the skin, scratching the area may transfer the urushiol to other unexposed skin surfaces. Unwashed, contaminated hands and fingernails are the primary sources of rash on protected areas of the body.

- As the dermatitis progresses, vesicles or bullae form, depending on the patient’s sensitivity. The vesicles/bullae may break open, releasing their fluid. Vesicular fluid does not contain any antigenic material to further spread the dermatitis.

- Oozing and weeping of the vesicular fluid continues to occur for several days, until the affected area develops crusts and begins to dry.

- The initial dermal reaction in urushiol-induced dermatitis is an intense itching of the exposed skin surfaces, followed by erythema. Itching may be more intense in older patients than in younger adults.

- Allergic contact dermatitis resolves within 10–21 days, with or without treatment, as a result of the patient’s own immune system.

Treatment

Treatment

Treatment of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

Treatment of Irritant Contact Dermatitis

- Treatment of irritant contact dermatitis is directed at removing the offending agent; preventing future exposure to the irritant; and reducing inflammation, dermal tenderness, and irritation.

- Educating patients about ways to reduce risk of exposure to known irritants is fundamental.

- Protective clothing, gloves, or other equipment should be worn at all times.

- Patients should limit the time skin areas are occluded by making frequent changes in coverings.

- The barrier products Hydropel and Hollister Moisture Barrier Cream claim to prevent irritant contact dermatitis if they are applied before contact with an irritant.

- Protective clothing, gloves, or other equipment should be worn at all times.

- Immediately washing exposed areas will reduce contact time with the irritant and help to localize symptoms if a dermal response occurs.

- Exposed areas should be washed with copious amounts of tepid water and cleansed with a mild or hypoallergenic soap (e.g., Dove or Cetaphil).

- Colloidal oatmeal baths may be helpful in relieving associated itching.

- Liberal application of emollients to the affected area will help restore moisture to the stratum corneum and serve as a protectant from further exposure to the effects of a wet working environment.

- Topical corticosteroids have questionable efficacy in the treatment of irritant contact dermatitis and are generally not considered optimal therapy.

- The use of topical “caine”-type anesthetics (e.g., benzocaine) should be avoided because of their ability to cause allergic contact dermatitis.

Treatment of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Treatment of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- Treatment of allergic contact dermatitis is directed at removing the offending agent when possible; reducing inflammation; relieving itching and preventing excessive scratching; and removing the accumulation of debris associated with oozing, crusting, and scaling of vesicles.

- The first several days following the initial appearance of allergic contact dermatitis usually are associated with greatest patient discomfort.

- Removing the known antigen from the skin as soon as possible may reduce the chance and/or severity of the immune response

- Whenever possible, areas of contact should be washed immediately using mild soap and tepid water.

- In cases of poison ivy/oak/sumac dermatitis, initial cleansing or rinsing of the affected area must take place within the first 10 minutes of exposure to reduce the immune response. However, washing within 30 minutes after exposure still is useful in removing any unreacted urushiol that remains on the skin’s surface and has not entered the dermal layers.

- “In the field” washing is difficult, but rinsing the area with large volumes of water will assist in removing much of the oleoresin.

- At the earliest convenience after the initial rinsing, patients should take a shower (rather than a bath) using mild soap and water. Tub baths should be avoided right after exposure because oleoresin may remain in the tub and affect unexposed areas.

- Thorough handwashing, including meticulous cleansing under the fingernails, is necessary to avoid transferring trapped urushiol to uncontaminated skin surfaces.

- “In the field” washing is difficult, but rinsing the area with large volumes of water will assist in removing much of the oleoresin.

- Tecnu Outdoor Skin Cleanser is marketed specifically as a cleanser for urushiol. It contains mineral spirits, water, soap, and a surface-active agent; it was originally developed as an agent to wash away radioactive matter from the skin surface of exposed individuals.

- Tecnu Outdoor Skin Cleanser is used after exposure. It should be rubbed into the affected area as soon after exposure as possible but can be used up to 8 hours after exposure. The patient should cleanse the contaminated area for a minimum of 2 minutes.

- No water is required for the initial cleansing. The cleanser may be wiped away with a cloth if rinsing with cool water is not possible.

- Tecnu should be used before eating, smoking, or using the bathroom to minimize transfer of urushiol to uncontaminated skin.

- Tecnu Outdoor Skin Cleanser is used after exposure. It should be rubbed into the affected area as soon after exposure as possible but can be used up to 8 hours after exposure. The patient should cleanse the contaminated area for a minimum of 2 minutes.

Nonpharmacologic Treatments for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- The primary nondrug measure for relieving symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis is taking cold or tepid soapless showers to temporarily relieve pruritus.

- A tepid shower is approximately 90°F (32.2°C) or cooler. Hot showers (temperatures >105°F [40.5°C]) can intensify the pruritus.

- Patients should avoid using harsh soaps or vigorously scrubbing areas where rash is present.

- A tepid shower is approximately 90°F (32.2°C) or cooler. Hot showers (temperatures >105°F [40.5°C]) can intensify the pruritus.

- Fingernails should be trimmed to minimize scratching and possible injury to the affected area.

- Bathing in tepid water containing colloidal oatmeal is an option for cleansing and soothing larger areas of nonweeping lesions. However, this measures is considered to have limited efficacy for reducing pruritus.

- Patients use one packet (30 grams) of colloidal oatmeal or 1 cup of finely milled oatmeal per tub of water.

- The oatmeal should be sprinkled into fast-running water to allow for good mixing. Stirring the bath water occasionally helps to prevent lumps from developing.

- Patients should soak in an oatmeal bath for 15 or 20 minutes at least twice per day.

- The skin should be patted dry (not wiped) to leave a film of colloidal oatmeal on the skin.

- Colloidal oatmeal makes the bathtub extremely slippery. Placing a rubber mat in the tub and a dry rug or towel on the floor will help prevent falling.

- Patients use one packet (30 grams) of colloidal oatmeal or 1 cup of finely milled oatmeal per tub of water.

- The astringents aluminium acetate (Burow’s solution) and witch hazel (hamamelis water) retard oozing, discharge, or bleeding from dermatitis; they also cleanse the skin of exudates, crust, and debris.

- A 1:40 dilution of Burow’s solution is prepared from prepackaged tablets or powder by adding one tablet or the contents of one packet to 1 pint of cool tap water.

- Patients may soak the affected area in the solution two to four times daily for 15–30 minutes.

- Alternatively, patients may loosely apply a compress of washcloths, cheesecloth, or small towels; the compress is prepared by soaking the materials in the solution and then gently wringing them so that they are wet but not dripping. The dressings should be rewetted and applied every few minutes for 20–30 minutes, four to six times daily.

- Any remaining solution should be discarded and a fresh solution prepared for each application.

- A 1:40 dilution of Burow’s solution is prepared from prepackaged tablets or powder by adding one tablet or the contents of one packet to 1 pint of cool tap water.

Pharmacologic Treatments for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- Hydrocortisone cream 1% is the most effective form of topical therapy for treating symptoms of mild-to-moderate allergic contact dermatitis that does not involve edema and extensive areas of the skin.

- Ointments may intensify itching during the early stages of allergic contact dermatitis. They also may trap bacteria beneath the oleaginous film, leading to secondary infections.

- Hydrocortisone should not be applied to the eyes or eyelids.

- Although hydrocortisone cream usually is applied twice daily, frequent showering or use of cold water or Burow’s solution compresses may necessitate application up to four times daily.

- Ointments may intensify itching during the early stages of allergic contact dermatitis. They also may trap bacteria beneath the oleaginous film, leading to secondary infections.

- Oral antihistamines with sedating effects (e.g., cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, and diphenhydramine) can be used to help relieve itching. Bedtime administration is especially useful for itching that interferes with patients’ sleep. (Consult the “Allergic Rhinitis” and “Insomnia” chapters for more detailed information about sedating oral antihistamines.)

- If itching is not alleviated by nonprescription antihistamines, patients should be referred to their primary care provider for a prescription product. Hydroxyzine, cyproheptadine, and doxepin are all highly effective for itching.

- Topical ointments and creams containing anesthetics (e.g., benzocaine), antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine), or antibiotics (e.g., neomycin) should not be used to treat allergic contact dermatitis. These agents are known sensitizers and can cause a drug-induced dermatitis on top of the existing allergic contact dermatitis.

Preventive and Protective Measures for Urushiol-Associated Allergic Contact Dermatitis

- Preventive and protective measures for patients at risk for poison ivy/oak/sumac dermatitis are listed in Table 2. Additional information about bentoquatam is provided here.

- IvyBlock Lotion is a barrier product approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to provide protection against exposure to poison ivy, oak, and sumac. It contains 5% bentoquatam—a nonsensitizing and nonirritating organoclay—in an alcohol-based lotion. Bentoquatam is believed to physically block urushiol from being absorbed into the skin.

- The lotion should be shaken vigorously and applied generously to clean, dry skin likely to be exposed to poison ivy, oak, or sumac. The lotion leaves a smooth, wet film of lotion where it is applied; patients should check for a faint white coating that appears when the lotion has dried.

- The lotion should be applied at least 15 minutes before exposure to Toxicodendron plants. It should be reapplied once every 4 hours or as needed after the initial application to maintain effective protection.

- After the period of exposure has ended, the patient may remove the lotion by washing with soap and water.

- IvyBlock Lotion is a barrier product approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to provide protection against exposure to poison ivy, oak, and sumac. It contains 5% bentoquatam—a nonsensitizing and nonirritating organoclay—in an alcohol-based lotion. Bentoquatam is believed to physically block urushiol from being absorbed into the skin.

TABLE 2. Preventive and Protective Measures for Poison Ivy/Oak/Sumac Dermatitis

Preventive Measures

Learn the physical characteristics and usual habitat of Toxicodendron plants.

Learn the physical characteristics and usual habitat of Toxicodendron plants.

Eradicate Toxicodendron plants near your residence either by mechanically removing the plant and its roots, or by applying a herbicide recommended by the state farm bureau or the USDA extension services.

Eradicate Toxicodendron plants near your residence either by mechanically removing the plant and its roots, or by applying a herbicide recommended by the state farm bureau or the USDA extension services.

Apply bentoquatam on exposed areas of the body to reduce the risk of contamination before visiting an outdoor site. Repeat application every 4 hours until your potential exposure has ended. This application should be followed by flushing the area with water to remove bentoquatam and any urushiol deposited on the skin surface.

Apply bentoquatam on exposed areas of the body to reduce the risk of contamination before visiting an outdoor site. Repeat application every 4 hours until your potential exposure has ended. This application should be followed by flushing the area with water to remove bentoquatam and any urushiol deposited on the skin surface.

Survey the area of an outdoor visit, identify surrounding plants, and assess potential risk for exposure to Toxicodendron plants.

Survey the area of an outdoor visit, identify surrounding plants, and assess potential risk for exposure to Toxicodendron plants.

Protective Measures

Wear protective clothing to cover exposed areas.

Wear protective clothing to cover exposed areas.

Cover the nose and mouth with a protective mask when removing or eradicating Toxicodendron plants.

Cover the nose and mouth with a protective mask when removing or eradicating Toxicodendron plants.

Remove all clothing worn during exposure, and place the clothing directly into a washing machine. Wash this clothing separately from other clothes using ordinary detergent. If clothes must be dry cleaned, warn cleaning personnel of the possible contamination. Put contaminated clothing in a plastic bag for transport.

Remove all clothing worn during exposure, and place the clothing directly into a washing machine. Wash this clothing separately from other clothes using ordinary detergent. If clothes must be dry cleaned, warn cleaning personnel of the possible contamination. Put contaminated clothing in a plastic bag for transport.

As soon after use as possible, thoroughly wash with soap and water—or with water alone—any shoes, gloves, jackets, or other protective garments; sports equipment; garden and work tools; and any equipment that is capable of carrying urushiol. Wear vinyl gloves when washing contaminated objects.

As soon after use as possible, thoroughly wash with soap and water—or with water alone—any shoes, gloves, jackets, or other protective garments; sports equipment; garden and work tools; and any equipment that is capable of carrying urushiol. Wear vinyl gloves when washing contaminated objects.

Cleanse the fur of pets after known or suspected exposures to poison ivy plants.

Cleanse the fur of pets after known or suspected exposures to poison ivy plants.

USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Complications

Complications

- Patients who continue to scratch areas of contact dermatitis can excoriate the surface dermal layer, leading to open lesions and the potential for secondary wound infections.

- On rare occasions, various other diseases have been associated with exposure to Toxicodendron plants and the development of allergic contact dermatitis. These diseases have included eosinophilia (ordinarily seen with exposure to poison ivy), secondary mania, erythema multiforme, acute respiratory distress syndrome (caused by inhaling urushiol particles carried in smoke), renal failure, dyshydrosis of the hands and feet, and urethritis.

Cautions and Contraindications

Cautions and Contraindications

- Patients who present with a rash that causes edema of the eyelids, closes the eyelids, affects the external genitalia or anus, or produces massive areas of body rash or edema should be referred to a primary care provider.

Pharmacologic Treatments

Pharmacologic Treatments

- Hydrocortisone cream or ointment should not be applied to the eyes or eyelids.

- Systemic absorption of hydrocortisone is nominal when it is applied to intact skin. However, use of topical hydrocortisone over large surface areas, prolonged use, use with an occlusive dressing, or use when skin integrity is compromised can lead to systemic absorption.

- Patients should not use topical hydrocortisone on areas of dermatitis that (1) persist for longer than 7 days or (2) clear and then reappear in a few days, unless such use has been approved by a primary care provider.

Special Populations

Special Populations

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric Patients

- Treatment of contact dermatitis in pediatric patients is similar to the approach in adults.

- Pharmacologic products should not be used in children <2 years, except as directed by a primary care provider.

- Use of bentoquatam lotion is not recommended for children <6 years of age, except as directed by a primary care provider.

Follow-Up

Follow-Up

- Patients with contact dermatitis should see a slow but steady reduction in itching, weeping, and dermatitis after 5–7 days of therapy. Complete remission may take up to 3 weeks.

- Pharmacists may choose to follow up with patients after several days of self-treatment. Alternatively, they may encourage patients to call for additional advice if pruritus has not subsided significantly within 5–7 days.

- If follow-up reveals that the patient’s rash has increased significantly in size, affects the eyes or genitals, or covers extensive areas of the face, the patient should be encouraged to consult with a primary care provider.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree