The number of Iranians exposed to chemical weapons during the war

1,000,000 people

The number of Iranians who received medical care during their exposures to chemical gases

100,000 people

Iranians killed by the immediate effects of chemical agents

5500 (3500 people by nerve agents and 2000 people by mustard gas)

Total Iranian mortalities due to chemical warfare agents during the war

25,000

Iranians veterans who exposed to chemical agents (registered and not registered)

40,000–70,000 people

Iranian civilians who exposed to chemical agents (registered and not registered)

35,000 people

Despite passing 25 years after the ceasefire, the chemical war victims are one of the main health challenges in Iran that unfortunately leads to deaths due to complications of SM poisoning. An estimate of the number of Iranian morbidities and mortalities due to chemical exposures during Iran-Iraq war are presented in Table 5.1 (Ghanei et al. 2003a; Salamati et al. 2013).

5.3 Delayed Complications of SM Poisoning

5.3.1 Distribution of Delayed SM Complications in Various Organs

Effects of SM on body organs are divided into acute and chronic/delayed phases. While the term “chronic” complications is referred to occupational exposure, “delayed” or “late” complications seems to be more suitable for long-term SM effects following battle-field exposure (Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006).

In delayed phase of SM intoxication, incidence of organ involvement, have been reported differently in various Iranian soldiers and also at different time intervals. As the first report of delayed toxic effects of SM poisoning, Balali-Mood (1984) evaluated 236 Iranian SM victims 2–28 months after exposure and delayed SM complications were as follows: respiratory complications in 78 %, CNS in 45 %, dermatologic complications in 41 % and eye complications in 36 % of cases (Balali-Mood 1984). Balali-Mood (1992) evaluated delayed toxic effects of SM on different organs of 1428 Iranian chemical victims 3–9 years after exposure and reported the most SM complications in the respiratory tracts (90 %), skin (88 %), the eyes (78 %), neural system (71 %), gastrointestinal system (55 %), genitalia (52 %) and hematopoietic system (38 %) (Balali-Mood 1992). Holisaz et al. (2003) in a study on 100 Iranian chemical victims, reported dermatologic and ophthalmic complications in 94 %, pulmonary in 75 %, hematologic complications in 10 % and GI complications in 5 % of the victims (Holisaz et al. 2003). According to Khateri and co-workers (2003), the pulmonary, dermatologic and ophthalmic complications were the most common organ delayed complications among 34,000 SM victims (including from mild to severe intoxication). Balali-Mood et al. (2005a) described late toxic effects of SM poisoning in a group of 40 severely intoxicated Iranian veterans 16–20 years after exposure. The most commonly affected organs were lungs (95 %), peripheral nerves (77.5 %), the skin (75 %) and the eyes (65 %) (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a). More recently, Namazi and colleagues (2009) studied 134 patients with delayed complications of SM poisoning and reported the lungs (100 %), the skin (82.84 %) and the eyes (77.61 %) as the most frequent affected organs (Namazi et al. 2009). Distribution of SM delayed complications in different organs were listed in Table 5.2, according to several studies in Iran.

Table 5.2

Distribution of delayed complications of SM poisoning in various organs based on several studies in Iran

Author(s) | Publication year | Population | Case numbers | Distribution of complications | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Balali-Mood et al. | 1984 (2–28 month after exposure) | Veterans | 236 | Respiratory tract (78 %), CNS (45 %), skin (41 %), eyes (36 %) | Balali-Mood (1984) |

Shirazi and Balali-Mood | 1987 (2 years after exposure) | Veterans | 77 | Lungs (58 %), eyes (46 %), skin (38 %) | Shirazi and Balali-Mood (1988) |

Balali-Mood | 1992 (3–9 years after exposure) | Veterans | 1428 | Lungs (90 %), skin (88 %), eyes (78 %), neural system (71 %), gastrointestinal system (55 %), hematopoietic system (38 %) | Balali-Mood (1992) |

Khateri et al. | 2003 (13–20 years after exposure) | Veterans, civilians | 34,000 (mild to severe exposure) | Lungs (42.5 %), eyes (39 %), skin (24.2 %) | Khateri et al. (2003) |

Holisaz et al. | 2003 (14–20 years after exposure) | Veterans | 100 | Skin (94 %), eyes (94 %), lungs (75 %), hematopoietic system (10 %), gastrointestinal system (5 %) | Holisaz et al. (2003) |

Balali-Mood et al. | 2005 (16–20 years after exposure) | Veterans | 40 | Lungs (95 %), peripheral nerves (77.5 %), skin (75 %), eyes (65 %) | Balali-Mood et al. (2005b) |

Etezad-Razavi et al. | 2006 (16–20 years after exposure) | Veterans | 40 | Lungs (95 %), skin (90 %), eyes (65 %) | Etezad-Razavi et al. (2006) |

Ghasemi-Boroumand et al. | 2008 (19 years after exposure) | Civilians | 600 | Lungs (45.8 %), eyes (37.7 %), skin (31.5 %) | Ghassemi-Broumand et al. (2008) |

Namazi et al. | 2009 (17–22 years after exposure) | Veterans | 134 | Lungs (100 %), skin (82.84 %), eyes (77.61 %) | Namazi et al. (2009) |

Zojaji et al. | 2009 (17–22 years after exposure) | Veterans | 43 | Lungs (95 %), peripheral nerves (77 %), skin (73 %), eyes (68 %) | Zojaji et al. (2009) |

5.3.2 Delayed Respiratory Complications

Respiratory problems are the greatest cause of long-term disability among Iranian veterans with combat-exposure to SM gas. Khateri et al. (2003) in a study conducted on 34,000 Iranians who were exposed to SM, reported that 14,450 (42.5 %) of them were suffering from respiratory problems (Khateri et al. 2003). Respiratory complications exacerbate over time while cutaneous and ocular injuries tend to either alleviate or remain invariable (Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2005b; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006; Ghanei and Adibi 2007; Khateri et al. 2003). Comparison of acute and late toxic effects of SM poisoning in 77 Iranian CWA victims indicated that dermal complications tend to decrease, eye lesions do not change significantly, and respiratory complications generally deteriorate over the years (Zarchi et al. 2004). Even those veterans who had not developed acute symptoms of SM (sub-clinical exposure) may suffer from late respiratory complications (Ghanei and Adibi 2007; Ghanei et al. 2004a).

In the long-term phase of SM intoxication, a triad of cough, expectoration and dyspnea has been found as the most respiratory symptoms among Iranian SM veterans (Balali-Mood 1992; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006; Darchini-Maragheh et al. 2011). Generalized wheezing is the most objective finding in delayed phase of respiratory complications (Balali-Mood and Balali-Mood 2009). Crackles, clubbing, decreased lung sounds and cyanosis have been also reported as other common objective findings (Balali-Mood 1992; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006; Ghanei and Adibi 2007; Razavi et al. 2013a).

Spirometry is a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluation of pulmonary impairment during regular follow-ups of SM victims (Hefazi et al. 2005). Pulmonary function testing (PFT) had been revealed more obstructive pattern than restriction (Balali-Mood 1992). Although some investigators notice that obstructive pattern is still the most common spirometric finding among SM poisoned veterans, it seems that restrictive pattern has been increased over the years and reported as dominant pattern of spirometry among SM patients in more recent studies (Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2005b; Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Darchini-Maragheh et al. 2011; Ghanei and Adibi 2007; Ghanei et al. 2004a). Emad and Rezaian (1997) in a respiratory survey of 197 Iranian veterans 10 years after a heavy SM exposure, reported the diversity of the effect of SM on respiratory pattern according to possible lung fibrosis over the years based on spirometric findings and lung biopsies (Emad and Rezaian 1997).

Chest radiography has been shown an increased bronchovascular markings, hyperinflation, pneumonic infiltration, bronchiectasis and radiologic evidence of pulmonary hypertension (Bagheri et al. 2003; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006; Bijani and Moghadamnia 2002; Ghanei and Adibi 2007; Ghanei et al. 2004b). However, such radiography is not sensitive enough for detection of delayed respiratory complications among SM victims. High Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) is imaging modality of choice in diagnosis of SM pulmonary complications (Bagheri et al. 2003; Bakhtavar et al. 2008; Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Emad et al. 1995; Balali-Mood et al. 2011). An HRCT study in delayed phase of SM poisoning among Iranian veterans revealed that a series of delayed destructive pulmonary sequelae such as chronic bronchitis (58 %), asthma (10 %), bronchiectasis (8 %), large airway narrowing (9 %), and pulmonary fibrosis (12 %) were developed (Emad and Rezaian 1997). Furthermore, a respiratory survey of 40 severely SM intoxicated Iranian veterans (2005), reported main delayed respiratory complications as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (35 %), bronchiectasis (32.5 %), asthma (25 %), large airway narrowing (15 %), pulmonary fibrosis (7.5 %), and simple chronic bronchitis (5 %) (Hefazi et al. 2005).

As evidenced by a long-term follow-up study of 40 SM veterans conducted by Balali-Mood and co-workers (2005a), both the severity and frequency of bronchiectatic lesions tend to increase over the time (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a). Bronchiectasis usually begins bilaterally in the lower lobes of the lungs and then has cephalic progression. Direct effects of SM on bronchial wall mucosa as well as recurrent respiratory infections among SM veterans are known to be responsible for development of bronchiectasis (Ghanei and Adibi 2007).

Hypoxemia and hypercapnia are observed in severe cases of bronchitis and in bronchiectatic lesions leading to pulmonary hypertension and core pulmonale in severe stages of the complications (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Ghanei et al. 2004a; Hosseini et al. 1998).

In the study of Ghanei et al. (2006a) on 300 symptomatic SM patients, 45.6 % had various degrees of air trapping. The study reported air trapping and tracheobronchomalacia as common delayed sequelae in SM exposed patients and hypothesized that SM may affect both small and large airways (Ghanei et al. 2006a). Furthermore, in an HRCT study of 50 Iranian patients with delayed respiratory complications of SM, air trapping (76 %), bronchiectasis (74 %) and mosaic parenchymal attenuation (72 %) were reported as the most frequent findings and revealed the diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) (Ghanei et al. 2004b). This was also proved by a later pathologic study (Beheshti et al. 2006). In a cross-sectional study conducted by Beheshti and colleagues (2006) on 23 patients with late complications of SM, main respiratory complications were diagnosed as air trapping (76 %) and bronchiectasis (74 %). It was also stated in the report that in nine lung biopsies out of 14, histopathological changes were diagnosed as BO (Beheshti et al. 2006). Although, this diagnosis should be corroborated by further histopathological studies, BO seems to be one of the main underlying pulmonary diseases in delayed SM intoxication and depends on host response rather than a dose response manner (Ghanei et al. 2008a).

Bronchoscopic appearance of airway mucosa has been reported to be a combination of erythema, chronic inflammatory changes and mucosal thickening in most of SM patients (Ghanei and Adibi 2007). Broncho-Alveolar Lavage (BAL) fluid analysis of SM patients has been revealed an ongoing local inflammatory process resulting in the development of pulmonary fibrosis, years after initial exposure (Emad and Rezaian 1997). Diffusing capacity of the lungs can be used as an objective monitor of the degree of lung fibrosis in SM patients and also as a good predictor of prognosis (Balali-Mood and Balali-Mood 2009). BAL fluid analysis of SM patients has been revealed increased inflammatory cells even more than two decades after SM exposure (Beheshti et al. 2006; Emad and Rezaian 1999; Sohrabpour et al. 1988). Increased neutrophil as well as eosinophil counts have been reported in BAL fluid analysis, which is more common in asthmatic respiratory conditions (Beheshti et al. 2006; Ghanei et al. 2005a). Inflammatory pattern of BAL analysis have been reported to be neutrophil dominant in some previous studies (Ghanei et al. 2007). Typical SM exposed patients have normal values of albumin and immunoglobulin (Ig) in the BAL fluid. However, those who were diagnosed as asthma show an increased IgG level (Ghanei et al. 2005a). Aghanouri and colleagues (2004) reported increased levels of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) as well as TGF-β1 receptors, in BAL fluid of SM-exposed patients compared with non-exposed individuals and concluded that since TGF-β1 can cause BO changes and is substantially increased in BAL aspirates and target tissue of SM patients, the role of BO as the main underlying pathology in mustard lung becomes evident (Aghanouri et al. 2004).

It is well known that SM is a mutagenic alkylating agent. In vitro studies, it have been shown that mustard is both mutagenic and carcinogenic. Human data from WWI battlefield exposure and among chemical factory workers, who have prolonged exposure with mustard compounds, reported increased risk of pulmonary carcinoma. However, figures failed to make a strong case, and there is controversy around a carcinogenic effect after a single low or high dose exposure (Ghanei and Harandi 2007). Also, there are no substantial reports regarding this issue on Iranian patients. Sparse cases of bronchogenic carcinoma have already been reported in Iranian veterans (Balali-Mood 1992; Zojaji et al. 2004). Thus, long-term follow-up is required to discover the incidence of lung carcinogenicity in such patients.

5.3.3 Delayed Ophthalmologic Complications

The eyes have the most sensitivity organ to SM which is attributed to several ocular features. The aqueous-mucous surface of the cornea and conjunctiva, as well as higher turnover rate and intense metabolic activity of corneal epithelial cells make remarkable hypersensitivity in the event of SM exposure (Etezad-Razavi et al. 2006; Namazi et al. 2009).

In the study of Namazi et al. (2009) on 134 Iranian SM veterans (2009), burning sensation, photophobia, red eye and itching were the most common delayed eye complications (Namazi et al. 2009). Balali-Mood and colleagues (2005a), through ophthalmologic examination of 40 SM intoxicated Iranian veterans, reported subjective eye complications in almost all the patients which were recorded as itching (42.5 %), burning sensation (37.5 %), photophobia (30 %), tearing (27.5 %), premature presbyopia with reading difficulties (10 %), ocular pain (2.5 %) and foreign body sensation (2.5 %). Common objective findings were found in the following order: chronic conjunctivitis (17.5 %), peri-limbal hyperpigmentation (17.5 %), corneal thinning (15 %), vascular tortuosity (15 %), limbal ischaemia (12.5 %), corneal opacity (10 %), corneal vascularization (7.5 %) and corneal epithelial defect (5 %) (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a). Ghasemi et al. (2008) studied 367 chemical war victims of Sardasht, Iran and reported that photophobia and ocular surface discomfort (burning, itching and redness) were the most significant symptoms, while, bulbar conjunctival abnormality and limbal tissue changes were the most slit-lamp findings among the victims (Ghasemi et al. 2008).

Although most of early ocular complications of SM exposure such as lacrimation, edema, discharge and even blindness usually recover after a few days to weeks, a kind of delayed ulcerative keratopathy may develop, leading to permanent residual effects (Etezad-Razavi et al. 2006). This usually occurs 15–20 years after the initial injury and starts with a sudden onset of photophobia, tearing and decreasing vision (Javadi et al. 2007). It is characterized by corneal thinning, corneal opacification, neovascularization, and corneal epithelial deficiency advances after a symptom-free period (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Etezad-Razavi et al. 2006). In acute stages of ulcerative keratitis, the limbal region frequently presents a marbled appearance in which porcelain-like areas of ischaemia are surrounded by blood vessels with irregular diameters. Then, vascularized scars of the cornea are covered with crystal and cholesterol deposits, leading to worsening of opacification, recurrent ulcerations, and sometimes corneal perforation (Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2006). Opacification is seen in lower and central portions of cornea, whereas the upper part is almost protected due to eyelids (Balali-Mood and Balali-Mood 2009; Balali-Mood et al. 2008). Lesions were surprisingly recurring even after corneal transplantation (Javadi et al. 2005). Etezad-Razavi (2006) noticed delayed ulcerative keratitis, as a delayed objective finding in 15 % of the patients which in comparison to a 0.5–1 % incidence of delayed keratitis observed in the WWI SM casualties, was significantly higher (Etezad-Razavi et al. 2006). Interestingly, the severity of the initial exposure and duration of the ophthalmic symptoms is directly related to the likelihood of later keratopathy (Ghasemi et al. 2009).

In a recent cross-sectional study on 40 severely intoxicated Iranian veterans with delayed complications of SM exposure (2013), retinal electrophysiological evaluations including electroretinography (ERG) and electrooculography (EOG) were performed. The study, as the first report on the SM-induced delayed-onset functional retinal changes, showed a general reduction of retinal photoreceptor function in delayed phase of SM exposure. This effect involves both cone and rod photoreceptors in terms of amplitude and implicit time. These findings among SM veterans showed that SM intoxication also have long-term complications on the eyes neurologic tissues such as retina (Darchini-Maragheh et al. 2013).

5.3.4 Delayed Dermal Complications

The lipophilic nature of SM and high affinity of the skin for lipophilic substances, make the skin an appropriate transporting system for this agent. Acute skin injury with SM without vesicle formation is almost always followed by a complete healing (Balali-Mood and Balali-Mood 2009; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2005b). In contrast, blisters and necrotic wounds cause permanent residual effects. Most of delayed cutaneous skin lesions are on the site of blisters at the acute phase of SM poisoning. Furthermore, previously injured sites have been reported to be sensitive to subsequent mechanical injury and showed recurrent blistering after mild injury (Fekri et al. 1992).

Balali-Mood in the first report of delayed SM skin complications 2 years after exposure among 236 Iranian veterans declared hyperpigmentation (34 %), hypopigmentation (16 %), and dermal scar (8 %) as the most common findings. The most common skin complaint among these patients was itching followed by a burning sensation and desquamation (Balali-Mood and Navaeian 1986). Several years later, pruritus was still the most common subjective finding (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Panahi et al. 2008). Balali-Mood et al. (2005a) and Panahi et al. (2008) reported hyperpigmentation and xerosis as the most frequent objective findings 16–20 years after SM exposure. Fekri et al. (1992) compared cutaneous lesions of 500 SM-exposed Iranian veterans with unexposed veterans. Significant association was reported between SM exposure and late skin lesions such as severe dry skin, hyper- and hypopigmentation, local hair loss, eczema, and chronic urticaria. Moreover, higher incidence of vitiligo, psoriasis, and discoid lupus erythematosus was reported among SM poisoned patients. In the study of Hefazi and colleagues (2006), delayed cutaneous complications of SM poisoning 16–20 years after exposure among Iranian veterans, the main objective findings were hyperpigmentation (55 %), dry skin (40 %), multiple cherry angiomas (37.5 %), atrophy (27.5 %), and hypopigmentation (25 %).

Emadi et al. (2008) in a study on 800 war veterans 14–20 years after SM intoxication noticed that most of the patients (93 %), showed non-specific skin disorders, while only 5 % developed scars with different patterns principally at the sites of previous MG-induced skin injuries (Emadi et al. 2008).

Scarring, results from connective tissue hypertrophy and dysregulated fibroblast activity during wound repair. It can be incapacitating, especially in the genital area (Momeni et al. 1992). In a cross-sectional study on 43 SM Iranian patients conducted by Layegh and colleagues (2011), the main cutaneous complain was itching (23.30 %). The most common clinical diagnosis was multiple Cherry angioma (72.1 %), which were significantly more common in SM-exposed group than in the controls. Significant lower skin moisture and lipid content in the SM exposed veterans compared with control group was also reported, thus, decreased function of stratum corneum and lipid production was considered as a delayed SM skin effect (Layegh et al. 2011).

Histopathological examination of skin biopsies has been revealed non-specific findings such as epidermal atrophy, keratosis, and basal membrane hyperpigmentation. Non-specific fibrosis and melanophages have also been observed within the dermis (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a; Fekri et al. 1992; Hefazi et al. 2006).

Sparse case reports of skin malignancies have been reported up to now and no casual connection has been firmly stablished (Emadi et al. 2012). It could be concluded that cutaneous malignancies appear to be a late uncommon consequence of SM exposure (Firooz et al. 2011). However, it may need a longer period of time for a malignancy to occur.

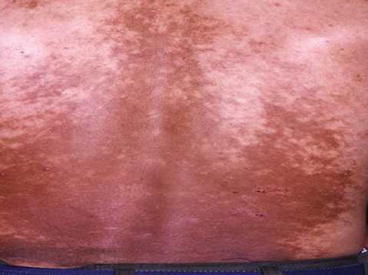

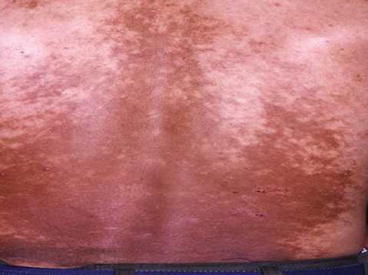

The skin hyper and hypo-pigmentaions of three patients with skin delayed complications of SM poisoning around 2 years after exposure are illustrated in Figs. 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3.

Fig. 5.1

Skin hyper and hypo-pigmentations of the neck of a patient around 2 years after SM exposure during the Iraq-Iran war (Unpublished slide of a SM veteran under Prof. Balali-Mood’s medical care, taken with permission of the patient)

Fig. 5.2

Skin hyper and hypopigmentation of the thorax of a patient around 2 years after SM exposure during the Iraq-Iran war (Unpublished slide of a SM veteran under Prof. Balali-Mood medical care, taken with permission of the patient)

Fig. 5.3

Skin hyper and hypopigmentation of the low back of a patient around 2 years after SM exposure during the Iraq-Iran war (Unpublished slide of a SM veteran under Prof. Balali-Mood medical care, taken with permission of the patient)

5.3.5 Delayed Neuropsychiatric Complications

In a study conducted by Namazi and colleagues (2009) on 134 patients with long-term complications of SM poisoning, the most common neurological complications were headache (26.86 %), epilepsy (16.42 %), vertigo (11.94 %), and tremor (4.48 %) (Namazi et al. 2009). In a survey of delayed neurological complications of SM poisoning (2012), sensory nerve impairments, including paresthesia (88.3 %), hyperesthesia (72.1 %) and hypoesthesia (11.6 %) were the most commonly observed clinical complications. Fatigue (93 %), paresthesia (88.3 %) and headache (83.7 %) were the most common subjective findings, while hyperesthesia (72.1 %) was the most objective finding.

Sparse delayed neurological complications of SM that were reported are mostly discussing about peripheral neuropathies and neuromuscular lesions. Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Velocity (NCV) findings showed abnormal pattern in seven SM patients (16.3 %) out of twelve patients who had the clinical indication for the experiments. NCV disrupted patterns were symmetric in both upper and lower extremities. Three patients had pure sensory polyneuropathy and four patients had sensory-motor distal polyneuropathy of axonal type. EMG pathologies contained chronic polyphasic motor unit action potential (MUAP) in distal tested muscles (Darchini-Maragheh et al. 2012). Balali-Mood et al. (2005a) reported 77.5 % peripheral neuropathy in 43 SM-intoxicated Iranian veterans with more sensory than motor nerve dysfunctions. It was also concluded that although late complications of SM are usually because of its direct toxic effect, neuromuscular complications are probably the result of systemic toxicity (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a). Even after electrophysiological procedures, approximately 50 % of polyneuropathies remain unrevealed (Darchini-Maragheh et al. 2012).

Exposure to CWA is an extreme traumatic event that has long-lasting adverse consequences on mental health. Long-term psychological symptoms of SM victims appear to be more related to the trauma caused by the war itself rather than SM poisoning per se. Strong association between physical illnesses and psychiatric disorders in chemical warfare survivors has been reported (Mansour Razavi et al. 2012). In addition, exposure to war, adverse physical health consequences and also fear of the future CWA exposure, represent an additive effect for involved and persistent mental health (Hashemian et al. 2006). Disorders of emotion (98 %), memory (80 %), behavior (80 %), attention (54 %), consciousness (27 %) and thought process (14 %) were reported in 70 SM patients 3–5 years after exposure (Balali-Mood 1986). Hashemian et al. (2006) reported in a cross-sectional study on long-term psychological impact of chemical warfare on a civilian population of Kurdish ethnicity, compared with individuals exposed to warfare, those exposed to warfare and chemical weapons were at higher risk for lifetime Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), increased anxiety and depressive symptoms (Hashemian et al. 2006). Roshan et al. (2013) compared 367 SM exposed civilians from Sardasht, Iran with matched control group and reported significantly more somatization, obsessive-compulsive, depression, anxiety and hostility among exposed civilians. In addition, significant differences between the two groups were reported regarding the Global Severity Index (GSI) and Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI). Razavi et al. (2014) in a review of articles has described long-term common psychiatric complications of SM exposure. The frequency of emotional problems was (98 %), memory impairment (80 %), behavioral abnormalities (80 %), social performance disturbances (10.73 %), anxiety (18–65 %), insomnia (13.63 %), low concentration (54 %), severe depression (6–46 %), personality disorders (31 %), thought processing disturbances (14 %), seizures (6 %), psychosis (3 %), based on reviewing valid published articles. Lifetime and current PTSD have been reported as 8–59 % and 2–33 % in the literature, respectively (Razavi et al. 2014). Vafaee and Seidy (2004) showed that the frequency of depression in physically injured victims was two times more than the control group and in chemically injured victims was two times more frequent than physically injured victims (Vafaee and Seidy 2004). Functional aphonia, photophobia, and dry eyes have also been previously reported in Iranian SM victims (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a).

5.3.6 Delayed Immuno-hematological Complications

SM can cause long-term effects on hematologic and immune system in patients with moderate and severe intoxication. While leukopenia and anemia were reported to be major acute hematological variations following SM exposure, the total red blood cell (RBC) count as well as hematocrit (Hct) level is higher than expected in long-term phase, due to hypoxemic status of SM patients as a result of respiratory problems. Long-term follow-up of Iranian veterans showed a significant increase in the percentage of the reticulocyte counts (Keramati et al. 2013). White Blood Cell (WBC) count is higher among SM exposed patients which is more attributed with recurrent respiratory infections in these patients rather than direct effects of SM on the bone marrow (Mahmoudi et al. 2005). Decrease in both cell-mediated and humoral immunity have been reported several years after exposure with SM among Iranian veterans (Ghotbi and Hassan 2002). Balali-Mood and colleagues (2005) reported long-term hematological and immunological complications of 40 patients with delayed complications of SM poisoning as follows: Total WBC and RBC counts as well as HCT level were significantly higher in SM group. The percentages of monocytes and CD3+ lymphocytes were significantly higher, while the percentage of natural killer cells was significantly lower in the SM patients. Serum IgM and C3 levels were significantly higher in the patients in comparison with the controls (Balali-Mood et al. 2005a). Riahi-Zanjani and colleagues (2014) reported lower levels of IL-1β, IL-8 levels and TNFα among SM poisoned Iranian veterans compared with a control group, but levels of other assayed cytokines including IL-2, -4, -5, -6, -10, -12, IFNγ and TNFβ were not significantly different between the two groups. Keramati and colleagues (2013) in a study on 42 Iranian SM-exposed and a control group, reported higher reticulocytes as well as lower total protein and albumin levels in veterans compared to the controls. In addition, significant increase of serum lipids and gamma-glutamyl transferase activity were also reported in the patients. In a study on 40 Iranian veterans with late complications of SM 16–20 years after exposure conducted by Mahmoudi and colleagues (2005), the percentages of monocytes and CD3+ T-lymphocytes were significantly lower in the patients. CD16 + 56 positive cells were significantly higher in patients than in the control group. IgM and C3, as well as absolute levels of α1, α2 and β globulins were also significantly higher in the patients (Mahmoudi et al. 2005). Hassan and Ebtekar (2002) demonstrated increased levels of IgG and IgM even 8 years after exposure to SM compared to the controls. Decreased number of natural killer cells (CD45+/CD56+) plus higher activity of natural killer cells (CD56+/CD25+) was also reported as long-term immunological complication of SM (Ghotbi and Hassan 2002). Impaired immunity, especially in the number of B and T lymphocytes, as a long-term complication of SM exposure could be responsible for increased risk of recurrent infections among SM victims (Balali-Mood 1986).

5.3.7 Other Delayed Complications

Knowledge about long-term mustard-induced cardiotoxic effects reveals possible relationship between SM and heart diseases. Ventricular diastolic abnormalities have been reported as late cardiac complication and were much more frequent than the ventricular systolic abnormalities in the literature (Gholamrezanezhad et al. 2007; Pishgoo et al. 2007; Rohani et al. 2010). Veterans exposed to SM have been shown lower functional capacity, reduced right ventricular function and elevated pulmonary artery pressure compared to the control group (Shabestari et al. 2013). Regarding to the respiratory disorders in the veterans, as one of the most common long-term SM complications, which can lead to the well-known cor-pulmonale, role of cardiac performance in occurrence of this phenomenon remains to be clear (Emad and Rezaian 1997).

Gholamrezanezhad et al. (2007), in scintigraphic myocardial perfusion scans of 22 veterans with late complications of SM exposure during the Iran-Iraq war, declared that patterns of myocardial perfusion in case group was completely different from the controls and was resembled to either coronary artery disease or mild cardiomyopathic changes. It was also noted that both dilated right ventricular chamber and ischemia were significantly more prevalent among SM patients (Gholamrezanezhad et al. 2007). Shabestari et al. (2011) in a study on 40 mustard-poisoned patients, reported coronary artery ectasia as the most finding of conventional angiography with a prevalence of 22.5 % versus 2.2 % in the control group. It was concluded that coronary ectasia occurs approximately 11 times more frequently in SM poisoned veterans, as a delayed complication. Karbasi-afshar and colleagues (2013) compared conventional angiography findings of Iranian veterans with late complications of SM exposure with unexposed grou and reported significantly higher incidence of atherosclerotic lesions among the SM patients, compared to the control group (Karbasi-Afshar et al. 2013).

Few studies are available regarding the urogenital and reproductive complications of SM, thus data on this issue are both lacking and contradictory. Soroush et al. (2009) in a survey of 289 Iranian male veterans, reported history of urinary calculi in 17.3 %, recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) 8.7 %, Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) 1.7 % and kidney failure in 0.7 % of the patients. In delayed phase of SM intoxication, the main target of gonadal effect injury is spermatogenesis (Panahi et al. 2013). Three years after SM exposure during Iran-Iraq war, infertile victims showed almost total atrophy of the seminiferous epithelium and intact interstitial cells. In addition, the infertile azoospermic in SM victims appeared to have a Sertoli cell only pattern in the testicular biopsy (Safarinejad 2001). Several years later, these findings were confirmed by Amirzargar and colleagues (2009) (Amirzargar et al. 2009). Balali-Mood (1992) reported significantly diminished sperm count among SM-exposed veterans in comparison to unexposed militants, 3–9 years post-exposure (Balali-Mood 1992). Azizi et al. (1995) also described reproductive effects of SM on Iranian veterans following battlefield exposure. The sperm count was less than 3 million cells/mL and the FSH level was higher comparing with that of normal men (Azizi et al. 1995). In contrast, results of another study by Ghanei et al. (2004c) failed to have an association between long-term infertility and SM exposure in residents of Sardasht, Iran. Although studies resulted in controversial findings, it seems that serum levels of the reproductive hormones are within the normal range in SM-exposed men several years post-exposure (Panahi et al. 2013). Ahmadi et al. (2014) reported the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in Iranian chemically injured veterans as 65.9 % as opposed to 33.0 % in non-chemically injured veterans. The most commonly affected domain in both groups was erectile dysfunction.

SM is considered as a suspected carcinogen CWA due to ability of chromatid aberration and inhibition of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis and thus classified as a carcinogen agent. Behravan and colleagues (2013) measured DNA breaks using single-cell microgel electrophoresis technique under alkaline conditions (Comet assay) after 25 years of SM exposure in Iranian veterans, and reported significant higher lymphocyte DNA damage in SM-exposed individuals compared with a matched control group (Behravan et al. 2013). In addition, Point mutations of p53 consistent with SM-induced DNA damage have been observed in some Iranian victims with lung cancer (Hosseini-khalili et al. 2009). Although former reports are available on excessive occurrence of malignancies after the WWI and in high-dose occupational exposures, there are sparse studies reporting higher occurrence of malignancies among chemical victims of Iran-Iraq war. Bronchogenic carcinoma, as well as carcinoma of the nasopharynx, thyroid cancer, adenocarcinoma of the stomach, acute myeloblastic and lymphoblastic leukemia, have been case reported in Iranian SM veterans (Balali-Mood 1992; Balali-Mood and Hefazi 2005a; Ghanei and Vosoghi 2002; Zojaji et al. 2009).

In a group of 500 Iranian SM-exposed patients compared with 500 unexposed soldiers 18 years post-exposure, only three cases with malignancies were found among the exposed veterans. Although no such cases occurred in the unexposed group, there was no significant correlation between cancer occurrence and exposure to SM (Gilasi et al. 2006). Therefore, as quantitative risk assessment cannot be developed from the available data, long-term follow-up is required to discover the incidence of carcinogenicity among Iranian SM victims.

As SM distributes systematically, it may affect several body organs. Iran is within the few countries faced several massive high-dose SM exposures. Thus, the literature should be made in Iran, and it seems a must for the Iranian scientists to investigate all other possible effects of SM.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree