D

Decerebrate posture

[Decerebrate rigidity, abnormal extensor reflex]

Decerebrate posture is characterized by adduction (internal rotation) and extension of the arms, with the wrists pronated and the fingers flexed. The legs are stiffly extended, with forced plantar flexion of the feet. In severe cases, the back is acutely arched (opisthotonos). This sign indicates upper brain stem damage, which may result from primary lesions, such as infarction, hemorrhage, or tumor; metabolic encephalopathy; head injury; or brain stem compression associated with increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Decerebrate posture may be elicited by noxious stimuli or may occur spontaneously. It may be unilateral or bilateral. With concurrent brain stem and cerebral damage, decerebrate posture may affect only the arms, with the legs remaining flaccid. Or, decerebrate posture may affect one side of the body and decorticate posture the other. The two postures may also alternate as the patient’s neurologic status fluctuates. Generally, the duration of each posturing episode correlates with the severity of brain stem damage. (See Comparing decerebrate and decorticate postures, page 198.)

Your first priority is to ensure a patent airway. Insert an artificial airway and institute measures to prevent aspiration. (Don’t disrupt spinal alignment if you suspect spinal cord injury.) Suction the patient as necessary.

Your first priority is to ensure a patent airway. Insert an artificial airway and institute measures to prevent aspiration. (Don’t disrupt spinal alignment if you suspect spinal cord injury.) Suction the patient as necessary.Next, examine spontaneous respirations. Give supplemental oxygen, and ventilate the patient with a handheld resuscitation bag if necessary. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be indicated. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment handy, but be sure to check the patient’s chart for a do-not-resuscitate order.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After taking vital signs, determine the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Use the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) as a reference. Decerebrate posturing indicates the second-lowest measure of motor response, according to the GCS. Patients exhibiting this abnormal posturing have a decreased LOC and may be in a comatose state. Evaluate the pupils for size, equality, and response to light. Test deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) and cranial nerve reflexes, and check for doll’s eye sign.

Next, explore the history of the patient’s coma. If you’re unable to obtain this information, look for clues to the causative disorder, such as hepatomegaly, cyanosis, diabetic skin changes, needle tracks, or obvious trauma. If a family member is available, find out when the patient’s LOC began deteriorating. Did it occur abruptly? What did the patient complain of before he lost consciousness? Does he have a history of diabetes, liver disease, cancer, blood clots, or aneurysm? Ask about any accident or traumatic injury responsible for the coma.

Comparing decerebrate and decorticate postures

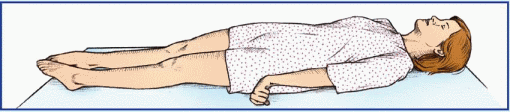

Decerebrate posture results from damage to the upper brain stem. In this posture, the arms are adducted and extended, with the wrists pronated and the fingers flexed. The legs are stiffly extended, with plantar flexion of the feet.

|

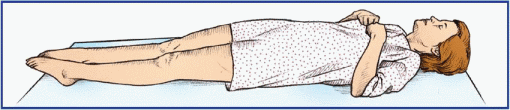

Decorticate posture results from damage to one or both corticospinal tracts. In this posture, the arms are adducted and the elbows are flexed, with the wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are stiffly extended and internally rotated, with plantar flexion of the feet.

|

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Brain stem infarction. Decerebrate posture may be elicited when this primary lesion produces a coma. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the severity of the infarct and may include cranial nerve palsies, bilateral cerebellar ataxia, and sensory loss. In a deep coma, all normal reflexes are usually lost, resulting in absence of doll’s eye sign, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and flaccidity.

♦ Brain stem tumor. In a brain stem tumor, decerebrate posture is a late sign that accompanies a coma. Early findings commonly include hemiparesis or quadriparesis, cranial nerve palsies, vertigo, dizziness, ataxia, and vomiting.

♦ Cerebral lesion. Whether the cause is trauma, tumor, abscess, or infarction, any cerebral lesion that increases ICP may also produce decerebrate posture, which is typically a late sign. Associated findings vary with the lesion’s site and extent but commonly include a coma, abnormal pupil size and response to light, and the classic triad of increased ICP—bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and widening pulse pressure.

♦ Hepatic encephalopathy. A late sign in this disorder, decerebrate posture occurs with a coma resulting from increased ICP and ammonia toxicity. Associated signs include fetor hepaticus (foul-smelling breath), a positive Babinski’s reflex, and hyperactive DTRs.

♦ Hypoglycemic encephalopathy. Characterized by extremely low blood glucose levels, this disorder may produce decerebrate posture and a coma. It also causes dilated pupils, bradypnea, and bradycardia. Muscle spasms, twitching, and seizures eventually progress to flaccidity.

♦ Hypoxic encephalopathy. Severe hypoxia may produce decerebrate posture—the result of brain stem compression associated with anaerobic metabolism and increased ICP. Other findings include a coma, a positive Babinski’s reflex, absence of doll’s eye sign, hypoactive DTRs, and possibly fixed pupils and respiratory arrest.

♦ Pontine hemorrhage. Typically, this lifethreatening disorder rapidly leads to decerebrate posture with a coma. Accompanying signs include total paralysis, absence of doll’s eye sign, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and small, reactive pupils.

♦ Posterior fossa hemorrhage. This subtentorial lesion causes decerebrate posture. Its early signs and symptoms include vomiting, headache, vertigo, ataxia, stiff neck, drowsiness, papilledema, and cranial nerve palsies. The patient eventually slips into a coma and may experience respiratory arrest.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Diagnostic tests. Removal of spinal fluid during a lumbar puncture to relieve high ICP may precipitate cerebral compression of the brain stem and cause decerebrate posture and a coma.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Help prepare the patient for diagnostic tests that will determine the cause of his decerebrate posture. These include skull X-rays, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, cerebral angiography, digital subtraction angiography, EEG, brain scan, and ICP monitoring.

Monitor the patient’s neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes or as indicated. Also, be alert for signs of increased ICP (bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and widening pulse pressure) and neurologic deterioration (altered respiratory pattern and abnormal temperature).

Inform the patient’s family that decerebrate posture is a reflex response—not a voluntary response to pain or a sign of recovery. Offer emotional support.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Children younger than age 2 may not display decerebrate posture because the nervous system is still immature. However, if this posture occurs, it’s usually the more severe opisthotonos. In fact, opisthotonos is more common in infants and young children than in adults and is usually a terminal sign. In children, the most common cause of decerebrate posture is head injury. It also occurs in Reye’s syndrome—the result of increased ICP causing brain stem compression.

Decorticate posture

[Decorticate rigidity, abnormal flexor response]

A sign of corticospinal damage, decorticate posture is characterized by adduction of the arms and flexion of the elbows, with wrists and fingers flexed on the chest. The legs are extended and internally rotated, with plantar flexion of the feet. This posture may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. It usually results from a stroke or head injury. It may be elicited by noxious stimuli or may occur spontaneously. The intensity of the required stimulus, the duration of the posture, and the frequency of spontaneous episodes vary with the severity and location of the cerebral injury.

Although a serious sign, decorticate posture carries a more favorable prognosis than decerebrate posture. However, decorticate posture may progress to decerebrate posture if the causative disorder extends lower in the brain stem. (See Comparing decerebrate and decorticate postures.)

Obtain vital signs and evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). If his consciousness is impaired, insert an oropharyngeal airway, and take measures to prevent aspiration (unless spinal cord injury is suspected). Evaluate the patient’s respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth. Prepare to assist respirations with a handheld resuscitation bag or with intubation and mechanical ventilation if necessary. Also, institute seizure precautions.

Obtain vital signs and evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). If his consciousness is impaired, insert an oropharyngeal airway, and take measures to prevent aspiration (unless spinal cord injury is suspected). Evaluate the patient’s respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth. Prepare to assist respirations with a handheld resuscitation bag or with intubation and mechanical ventilation if necessary. Also, institute seizure precautions.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Test the patient’s motor and sensory function. Evaluate pupil size, equality, and response to light. Then test cranial nerve function and deep tendon reflexes. Ask family members if the patient experienced headache, dizziness, nausea, changes in vision, numbness, or tingling. When did the patient first notice these symptoms? Is his family aware of any behavioral changes? Also, ask about a history of cerebrovascular disease, cancer, meningitis, encephalitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bleeding or clotting disorders, or recent trauma.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Brain abscess. Decorticate posture may occur in a brain abscess. Accompanying findings vary depending on the size and location of the abscess but may include aphasia, hemiparesis, headache, dizziness, seizures, nausea, and vomiting. The patient may also experience behavioral changes, altered vital signs, and decreased LOC.

♦ Brain tumor. A brain tumor may produce decorticate posture that’s usually bilateral—the

result of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) associated with tumor growth. Related signs and symptoms include headache, behavioral changes, memory loss, diplopia, blurred vision or vision loss, seizures, ataxia, dizziness, apraxia, aphasia, paresis, sensory loss, paresthesia, vomiting, papilledema, and signs of hormonal imbalance.

result of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) associated with tumor growth. Related signs and symptoms include headache, behavioral changes, memory loss, diplopia, blurred vision or vision loss, seizures, ataxia, dizziness, apraxia, aphasia, paresis, sensory loss, paresthesia, vomiting, papilledema, and signs of hormonal imbalance.

♦ Head injury. Decorticate posture may result from a head injury, depending on the site and severity of the injury. Associated signs and symptoms include headache, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, irritability, decreased LOC, aphasia, hemiparesis, unilateral numbness, seizures, and pupillary dilation.

♦ Stroke. Typically, a stroke involving the cerebral cortex produces unilateral decorticate posture, also called spastic hemiplegia. Other signs and symptoms include hemiplegia (contralateral to the lesion), dysarthria, dysphagia, unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, memory loss, decreased LOC, urine retention, urinary incontinence, and constipation. Ocular effects include homonymous hemianopsia, diplopia, and blurred vision.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Monitor the patient’s neurologic status and vital signs every 30 minutes to 2 hours. Be alert for signs of increased ICP, including bradycardia, increasing systolic blood pressure, and widening pulse pressure and subtle signs of neurologic deterioration.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Decorticate posture is an unreliable sign before age 2 because of nervous system immaturity. In children, this posture usually results from head injury, but it may also occur in Reye’s syndrome.

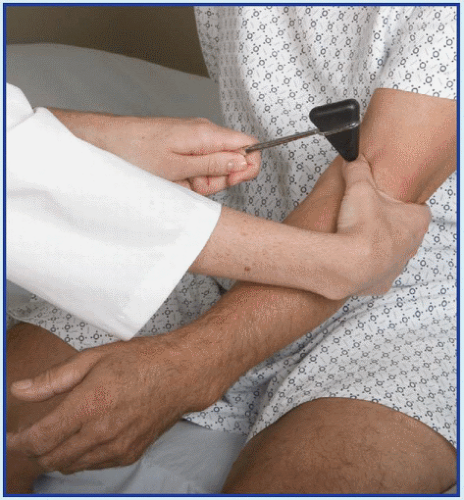

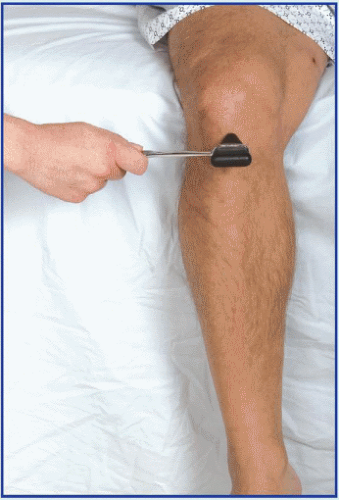

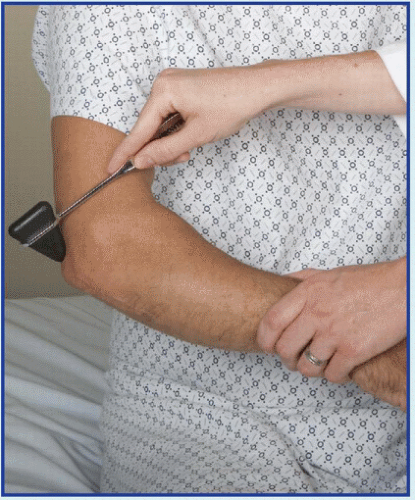

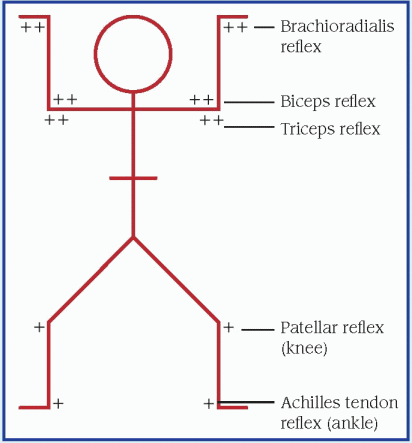

Deep tendon reflexes, hyperactive

A hyperactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally brisk muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of insertion. This elicited sign may be graded as brisk or pathologically hyperactive. Hyperactive DTRs are commonly accompanied by clonus.

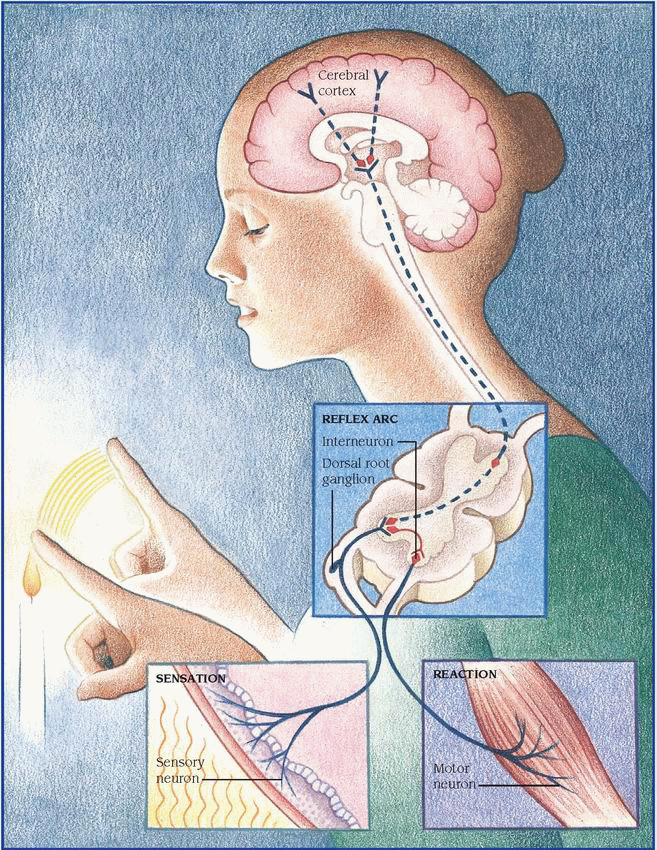

The corticospinal tract and other descending tracts govern the reflex arc—the relay cycle that produces any reflex response. A corticospinal lesion above the level of the reflex arc being tested may result in hyperactive DTRs. Abnormal neuromuscular transmission at the end of the reflex arc may also cause hyperactive DTRs. For example, a deficiency of calcium or magnesium may cause hyperactive DTRs because these electrolytes regulate neuromuscular excitability. (See The reflex arc, pages 202 and 203.)

Although hyperactive DTRs typically accompany other neurologic findings, they usually lack specific diagnostic value.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After eliciting hyperactive DTRs, take the patient’s history. Ask about spinal cord injury or other trauma and about prolonged exposure to cold, wind, or water. Could the patient be pregnant? A positive response to any of these questions requires prompt evaluation to rule out life-threatening autonomic hyperreflexia, tetanus, preeclampsia, or hypothermia. Ask about the onset and progression of associated signs and symptoms. Next, perform a neurologic examination. Evaluate level of consciousness, and test motor and sensory function in the limbs. Ask about paresthesia. Check for ataxia or tremors and for speech and visual deficits. Test for Chvostek’s sign (an abnormal spasm of the facial muscles elicited by light taps on the facial nerve in patients who have hypocalcemia) and Trousseau’s sign (a carpal spasm induced by inflating a sphygmomanometer cuff on the upper arm to a pressure exceeding systolic blood pressure for 3 minutes in patients who have hypocalcemia or hypomagnesemia) and for carpopedal spasm. Ask about vomiting or altered urination habits. Be sure to take vital signs.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. This disorder produces generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by weakness of the hands and forearms and spasticity of the legs. Eventually, the patient develops atrophy of the neck and tongue muscles, fasciculations, weakness of the legs and, possibly, bulbar signs (dysphagia, dysphonia, facial weakness, and dyspnea).

♦ Brain tumor. A cerebral tumor causes hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms develop slowly and may include unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

♦ Hepatic encephalopathy. Generalized hyperactive DTRs occur late and are accompanied by a positive Babinski’s reflex, fetor hepaticus, and a coma.

♦ Hypocalcemia. This disorder may produce sudden or gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs with paresthesia, muscle twitching and cramping, positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs, carpopedal spasm, and tetany.

♦ Hypomagnesemia. This disorder results in gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanied by muscle cramps, hypotension, tachycardia, paresthesia, ataxia, tetany and, possibly, seizures.

♦ Hypothermia. Mild hypothermia (90° to 94° F [32.2° to 34.4° C]) produces generalized hyperactive DTRs. Other signs and symptoms include shivering, fatigue, weakness, lethargy, slurred speech, ataxia, muscle stiffness, tachycardia, diuresis, bradypnea, hypotension, and cold, pale skin.

♦ Multiple sclerosis. Typically, hyperactive DTRs are preceded by weakness and paresthesia in one or both arms or legs. Associated signs include clonus and a positive Babinski’s reflex. Passive flexion of the patient’s neck may cause a tingling sensation down his back. Later, ataxia, diplopia, vertigo, vomiting, urine retention, or urinary incontinence may occur.

♦ Preeclampsia. Occurring in pregnancy of at least 20 weeks’ duration, preeclampsia may cause gradual onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs. Accompanying signs and symptoms include increased blood pressure; abnormal weight gain; edema of the face, fingers, and abdomen after bed rest; albuminuria; oliguria; severe headache; blurred or double vision; epigastric pain; nausea and vomiting; irritability; cyanosis; dyspnea; and crackles. If preeclampsia progresses to eclampsia, the patient develops seizures.

♦ Spinal cord lesion. Incomplete spinal cord lesions cause hyperactive DTRs below the level of the lesion. In a traumatic lesion, hyperactive DTRs follow resolution of spinal shock. In a neoplastic lesion, hyperactive DTRs gradually replace normal DTRs. Other signs and symptoms are paralysis and sensory loss below the level of the lesion, urine retention and overflow incontinence, and alternating constipation and diarrhea. A lesion above T6 may also produce autonomic hyperreflexia with diaphoresis and flushing above the level of the lesion, headache, nasal congestion, nausea, increased blood pressure, and bradycardia.

♦ Stroke. Any stroke that affects the origin of the corticospinal tracts causes sudden onset of hyperactive DTRs on the side opposite the lesion. The patient may also have unilateral paresis or paralysis, anesthesia, visual field deficits, spasticity, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

♦ Tetanus. In this disorder, sudden onset of generalized hyperactive DTRs accompanies tachycardia, diaphoresis, low-grade fever, painful and involuntary muscle contractions, trismus (lockjaw), and risus sardonicus (a masklike grin).

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to evaluate hyperactive DTRs. These may include laboratory tests for serum calcium magnesium and ammonia levels, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography scan, lumbar puncture, spinal X-rays, and myelography.

If motor weakness accompanies hyperactive DTRs, perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises to preserve muscle integrity and prevent deep vein thrombosis. Also, reposition the patient frequently, provide a special mattress, and massage his back and ensure adequate nutrition to prevent skin breakdown. Administer a muscle relaxant and a sedative to relieve severe muscle contractions. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment on hand. Provide a quiet, calm atmosphere to decrease neuromuscular excitability. Assist with activities of daily living, and provide emotional support.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Hyperreflexia may be a normal sign in neonates. After age 6, reflex responses are similar to those of adults. When testing DTRs in small children, use distraction techniques to promote reliable results.

Cerebral palsy commonly causes hyperactive DTRs in children. Reye’s syndrome causes generalized hyperactive DTRs in stage II and absent DTRs in stage V. Adult causes of hyperactive DTRs may also appear in children.

Deep tendon reflexes, hypoactive

A hypoactive deep tendon reflex (DTR) is an abnormally diminished muscle contraction that occurs in response to a sudden stretch induced by sharply tapping the muscle’s tendon of

insertion. It may be graded as minimal (+) or absent (0). Symmetrically reduced (+) reflexes may be normal.

insertion. It may be graded as minimal (+) or absent (0). Symmetrically reduced (+) reflexes may be normal.

Normally, a DTR depends on an intact receptor, intact sensory-motor nerve fiber, an intact neuromuscular-glandular junction, and a functional synapse in the spinal cord. Hypoactive DTRs may result from damage to the reflex arc involving the specific muscle, the peripheral nerve, the nerve roots, or the spinal cord at that level. Hypoactive DTRs are an important sign of many disorders, especially when they appear with other neurologic signs and symptoms. (See Documenting deep tendon reflexes.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After eliciting hypoactive DTRs, obtain a thorough history from the patient or a family member. Have him describe current signs and symptoms in detail. Then take a family and drug history.

Next, evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness. Test motor function in his limbs, and palpate for muscle atrophy or increased mass. Test sensory function, including pain, touch, temperature, and vibration sensation. Ask about paresthesia. To observe gait and coordination, have the patient take several steps. To check for Romberg’s sign, ask him to stand with his feet together and his eyes closed. During conversation, evaluate his speech. Check for signs of vision or hearing loss. Abrupt onset of hypoactive DTRs accompanied by muscle weakness may occur in life-threatening Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, or spinal cord lesions with spinal shock.

Look for autonomic nervous system effects by taking vital signs and monitoring for increased heart rate and blood pressure. Also, inspect the skin for pallor, dryness, flushing, or diaphoresis. Auscultate for hypoactive bowel sounds, and palpate for bladder distention. Ask about nausea, vomiting, constipation, and incontinence.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Botulism. In this disorder, generalized hypoactive DTRs accompany progressive descending muscle weakness. Initially, the patient usually complains of blurred and double vision and, occasionally, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Other early bulbar findings include vertigo, hearing loss, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The patient may have signs of respiratory distress and severe constipation marked by hypoactive bowel sounds.

♦ Cerebellar dysfunction. This disorder may produce hypoactive DTRs by increasing the level of inhibition through long tracts upon spinal motor neurons. Associated clinical findings vary depending on the cause and location of the dysfunction.

♦ Eaton-Lambert syndrome. This disorder produces generalized hypoactive DTRs. Early signs include difficulty rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and walking. The patient may complain of achiness, paresthesia, and muscle weakness that’s most severe in the morning. Weakness improves with mild exercise and worsens with strenuous exercise.

♦ Guillain-Barré syndrome. This disorder causes bilateral hypoactive DTRs that progress from hypotonia to areflexia in several days. Guillain-Barré syndrome typically causes muscle weakness that begins in the legs and then extends to the arms and, possibly, to the trunk and neck muscles. Occasionally, weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other signs and symptoms include cranial nerve palsies, pain, paresthesia, and signs of brief autonomic dysfunction, such as sinus tachycardia or bradycardia, flushing, fluctuating blood pressure, and anhidrosis or episodic diaphoresis.

Usually, muscle weakness and hypoactive DTRs peak in severity within 10 to 14 days; then symptoms begin to clear. However, in severe cases, residual hypoactive DTRs and motor weakness may persist.

♦ Peripheral neuropathy. Characteristic of end-stage diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and alcoholism, and as an adverse effect of various medications, peripheral neuropathy results in progressive hypoactive DTRs. Other effects include motor weakness, sensory loss, paresthesia, tremors and, possibly, signs of autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic hypotension and incontinence.

♦ Polymyositis. In this disorder, hypoactive DTRs accompany muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, spasms and, possibly, increased size or atrophy. These effects are usually temporary; their location varies with the affected muscles.

♦ Spinal cord lesions. Spinal cord injury or complete transection produces spinal shock, resulting in hypoactive DTRs (areflexia) below the level of the lesion. Associated signs and symptoms include quadriplegia or paraplegia, flaccidity, loss of sensation below the level of the lesion, and dry, pale skin. Also characteristic are urine retention with overflow incontinence, hypoactive bowel sounds, constipation, and genital reflex loss. Hypoactive DTRs and flaccidity are usually transient; reflex activity may return within several weeks.

♦ Syringomyelia. Permanent bilateral hypoactive DTRs occur early in this slowly progressive disorder. Other signs and symptoms are muscle weakness and atrophy; loss of sensation usually extending in a capelike fashion over the arms, shoulders, neck, back, and occasionally the legs; deep, boring pain (despite analgesia) in the limbs; and signs of brain stem involvement (nystagmus, facial numbness, unilateral vocal cord paralysis or weakness, and unilateral tongue atrophy). Syringomyelia is more common in males than in females.

♦ Tabes dorsalis. This progressive disorder results in bilateral hypoactive DTRs in the legs and occasionally the arms. Associated signs and symptoms include sharp pain and paresthesia of the legs, face, or trunk; visceral pain with retching and vomiting; sensory loss in the legs; ataxic gait with a positive Romberg’s sign; urine retention and urinary incontinence; and arthropathies.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Barbiturates and paralyzing drugs, such as pancuronium, may cause hypoactive DTRs.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Help the patient perform his daily activities. Try to strike a balance between promoting independence and ensuring his safety. Encourage him to walk with assistance. Make sure personal care articles are within easy reach, and provide an obstacle-free course from his bed to the bathroom.

If the patient has sensory deficits, protect him from injury from heat, cold, or pressure. Test his bath water, and reposition him frequently, ensuring a soft, smooth bed surface. Keep his skin clean and dry to prevent breakdown. Perform or encourage range-of-motion exercises. Also encourage a balanced diet with plenty of protein and adequate hydration.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Hypoactive DTRs commonly occur in children with muscular dystrophy, Friedreich’s ataxia, syringomyelia, or a spinal cord injury. They also accompany progressive muscular atrophy, which affects preschoolers and adolescents.

Use distraction techniques to test DTRs; assess motor function by watching the infant or child at play.

Depression

Depression is a mood disturbance characterized by feelings of sadness, despair, and loss of interest or pleasure in activities. These feelings may be accompanied by somatic complaints, such as changes in appetite, sleep disturbances, restlessness or lethargy, and decreased concentration. The patient also may have thoughts of death, suicide, or injuring herself.

Clinical depression must be distinguished from “the blues,” periodic bouts of dysphoria that are less persistent and severe than the clinical disorder. The criterion for major depression is one or more episodes of depressed mood, or decreased interest or ability to take pleasure in all or most activities, lasting at least 2 weeks.

Major depression strikes 10% to 15% of adults, affecting all racial, ethnic, age, and socioeconomic groups. It’s twice as common in women as in men and is especially prevalent among adolescents. Depression has numerous causes, including genetic and family history, medical and psychiatric disorders, and the use of certain drugs. It can also occur in the postpartum period. A complete psychiatric and physical examination should be conducted to exclude possible medical causes.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

During the examination, determine how the patient feels about herself, her family, and her environment. Your goal is to explore the nature of her depression, the extent to which other factors affect it, and her coping mechanisms and their effectiveness. Begin by asking what’s bothering her. How does her current mood differ from her usual mood? Then ask her to describe the way she feels about herself. What are her plans and dreams? How realistic are they? Is she generally satisfied with what she has accomplished in her work, relationships, and other interests? Ask about changes in her social interactions, sleep patterns, appetite, normal activities, or ability to make decisions and concentrate. Determine patterns of drug and alcohol use. Listen for clues that she may be suicidal. (See Suicide: Caring for the high-risk patient.)

Ask the patient about her family—its patterns of interaction and characteristic responses to success and failure. What part does she feel she plays in her family life? Find out if other family members have been depressed and whether anyone important to her has been sick or has died in the past year. Finally, ask the patient about her environment. Has her lifestyle changed in the past month? Six months? Year? When she’s feeling blue, where does she go and what does she do to feel better? Find out how she feels about her role in the community and the resources that are available to her. Try to determine if she has an adequate support network to help her cope with her depression.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Organic disorders. Various organic disorders and chronic illnesses produce mild, moderate, or severe depression. Among these are metabolic and endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and diabetes; infectious diseases, such as influenza, hepatitis, and encephalitis; degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and multi-infarct dementia; and neoplastic disorders such as cancer.

♦ Psychiatric disorders. Affective disorders are typically characterized by abrupt mood swings from depression to elation (mania) or by prolonged episodes of either mood. In fact, severe depression may last for weeks. More moderate depression occurs in cyclothymic disorders and usually alternates with moderate mania. Moderate depression that’s more or less constant over a 2-year period typically results from dysthymic disorders. Also, chronic anxiety disorders, such as panic and obsessivecompulsive disorder, may be accompanied by depression.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Alcohol abuse. Long-term alcohol use, intoxication, or withdrawal commonly produces depression.

♦ Drugs. Various drugs cause depression as an adverse effect. Among the more common are barbiturates, chemotherapeutic drugs such as asparaginase, anticonvulsants such as diazepam, and antiarrhythmics such as disopyramide. Other depression-inducing drugs include centrally acting antihypertensives, such as reserpine (common with high doses), methyldopa,

and clonidine; beta-adrenergic blockers such as propranolol; indomethacin; cycloserine; corticosteroids; and hormonal contraceptives.

and clonidine; beta-adrenergic blockers such as propranolol; indomethacin; cycloserine; corticosteroids; and hormonal contraceptives.

Suicide: Caring for the high-risk patient

One of the most common factors contributing to suicide is hopelessness, an emotion that many depressed patients experience. As a result, you’ll need to regularly assess a depressed patient for suicidal tendencies.

The patient may provide specific clues about her intentions. For example, you may notice her talking frequently about death or the futility of life, concealing potentially harmful items (such as knives and belts), hoarding medications, giving away personal belongings, or getting her legal and financial affairs in order. If you suspect that a patient is suicidal, follow these guidelines:

♦ First, try to determine the patient’s suicide potential. Find out how upset she is. Does she have a simple, straightforward suicide plan that’s likely to succeed? Does she have a strong support system (family, friends, a therapist)? A patient with low to moderate suicide potential is noticeably depressed but has a support system. She may have thoughts of suicide, but no specific plan. A patient with high suicide potential feels profoundly hopeless and has a minimal or no support system. She thinks about suicide frequently and has a plan that’s likely to succeed.

♦ Next, observe precautions. Ensure the patient’s safety by removing any objects she could use to harm herself, such as knives, scissors, razors, belts, electric cords, shoelaces, and drugs. Know her whereabouts and what she’s doing at all times; this may require one-on-one surveillance and placing the patient in a room that’s close to your station. Always have someone accompany her when she leaves the unit.

♦ Be alert for in-hospital suicide attempts, which typically occur when there’s a low staff-to-patient ratio—for example, between shifts, during evening and night shifts, or when a critical event such as a code draws attention away from the patient.

♦ Finally, arrange for follow-up counseling. Recognize suicidal ideation and behavior as a desperate cry for help. Contact a mental health professional for a referral.

♦ Postpartum period. Although its cause hasn’t been determined, postpartum depression occurs in about 10% to 20% of women who have given birth. Symptoms range from mild postpartum blues to an intense, suicidal, depressive psychosis.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Caring for a depressed patient takes time, tact, and energy. It also requires an awareness of your own vulnerability to feelings of despair that can stem from interacting with a depressed patient. Help the patient set realistic goals; encourage her to promote feelings of self-worth by expressing her opinions and making decisions. Try to determine her suicide potential, and take steps to help ensure her safety. The patient may require close surveillance to prevent a suicide attempt.

Make sure the patient receives adequate nourishment and rest, and keep her environment free from stress and excessive stimulation. Arrange for ordered diagnostic tests to determine if her depression has an organic cause, and administer prescribed drugs. Also arrange for follow-up counseling, or contact a mental health professional for a referral.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Because emotional lability is normal in adolescence, depression can be difficult to assess and diagnose in teenagers. Clues to underlying depression may include somatic complaints, sexual promiscuity, poor grades, and abuse of alcohol or drugs.

Use of a family systems model usually helps determine the cause of depression in adolescents. Once family roles are determined, family therapy or group therapy with peers may help the patient overcome her depression. In severe cases, an antidepressant may be required.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Many elderly patients have physical complaints, somatic complaints, agitation, or changes in intellectual functioning (memory impairment), making the diagnosis of depression difficult in these patients. Depressed older adults who are age 85 and older, have low self-esteem, and need to be in control have the highest risk of suicide. Even a frail nursing home resident with these characteristics may have the strength to kill herself.

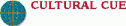

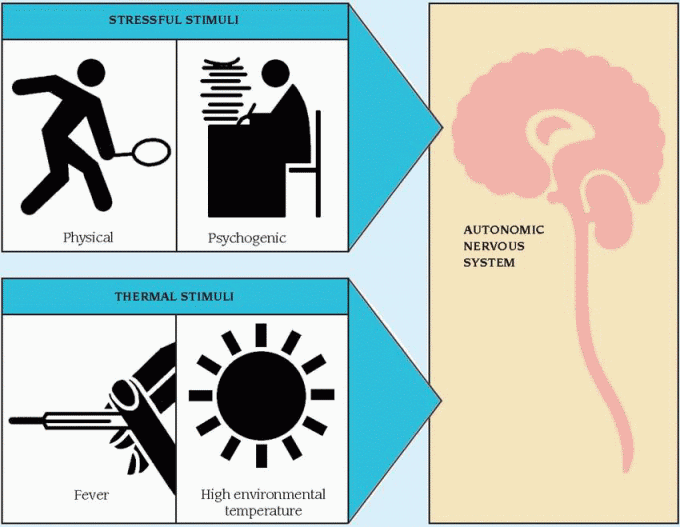

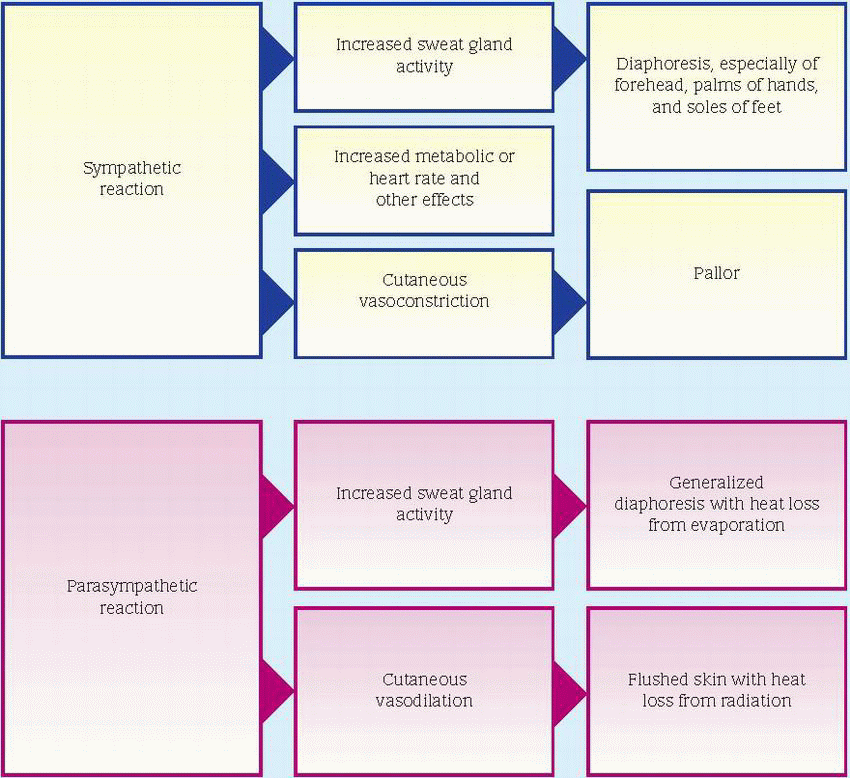

Diaphoresis

Diaphoresis is profuse sweating, sometimes amounting to more than 1 L of sweat per hour. This sign represents an autonomic nervous system response to physical or psychogenic stress, fever, or high environmental temperature. When caused by stress, diaphoresis may be generalized or limited to the palms, soles, and forehead. When caused by fever or high environmental temperature, it’s usually generalized.

Diaphoresis usually begins abruptly and may be accompanied by other autonomic system signs, such as tachycardia and increased blood pressure. However, this sign also varies with age because sweat glands function immaturely in infants and are less active in elderly people. As a result, patients in these age-groups may fail to display diaphoresis associated with its common causes. Intermittent diaphoresis may accompany chronic disorders characterized by recurrent fever; isolated diaphoresis may mark an episode of acute pain or fever. Night sweats may characterize intermittent fever because body temperature tends to return to normal between 2 A.M. and 4 A.M. before rising again. (Temperature is usually lowest around 6 A.M.)

Diaphoresis is a normal response to high external temperature. Acclimatization usually requires several days of exposure to high temperatures; during this process, diaphoresis helps maintain normal body temperature. Diaphoresis also commonly occurs during menopause, preceded by a sensation of intense heat (a hot flash). Other causes include exercise or exertion that accelerates metabolism, creating internal heat, and mild to moderate anxiety that helps initiate the fight-or-flight response. (See Understanding diaphoresis.)

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient is diaphoretic, quickly rule out the possibility of a life-threatening cause. (See When diaphoresis spells crisis, page 210.) Begin

the history by having the patient describe his chief complaint. Then explore associated signs and symptoms. Note general fatigue and weakness. Does the patient have insomnia, headache, and changes in vision or hearing? Is he often dizzy? Does he have palpitations? Ask about pleuritic pain, cough, sputum, difficulty breathing, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and altered elimination habits. Ask the female patient about amenorrhea and any changes in her menstrual cycle. Is she menopausal? Ask about paresthesia, muscle cramps or stiffness, and joint pain. Has she noticed any changes in elimination habits? Note weight loss or gain. Has she had to change her glove or shoe size lately?

the history by having the patient describe his chief complaint. Then explore associated signs and symptoms. Note general fatigue and weakness. Does the patient have insomnia, headache, and changes in vision or hearing? Is he often dizzy? Does he have palpitations? Ask about pleuritic pain, cough, sputum, difficulty breathing, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and altered elimination habits. Ask the female patient about amenorrhea and any changes in her menstrual cycle. Is she menopausal? Ask about paresthesia, muscle cramps or stiffness, and joint pain. Has she noticed any changes in elimination habits? Note weight loss or gain. Has she had to change her glove or shoe size lately?

Complete the history by asking about travel to tropical countries. Note recent exposure to high environmental temperatures or to pesticides. Did the patient recently experience an insect bite? Check for a history of partial gastrectomy or of drug or alcohol abuse. Finally, obtain a thorough drug history.

Next, perform a physical examination. First, determine the extent of diaphoresis by inspecting the trunk and extremities as well as the palms, soles, and forehead. Also, check the patient’s clothing and bedding for dampness. Note whether diaphoresis occurs during the day or at night. Observe the patient for flushing, abnormal skin texture or lesions, and an increased amount of coarse body hair. Note poor skin turgor and dry mucous membranes. Check for splinter hemorrhages and Plummer’s nails (separation of the fingernail ends from the nail beds).

Then evaluate the patient’s mental status and take his vital signs. Observe the patient for fasciculations and flaccid paralysis. Be alert for seizures. Note the patient’s facial expression, and examine the eyes for pupillary dilation or constriction, exophthalmos, and excessive tearing. Test visual fields. Also, check for hearing loss and for tooth or gum disease. Percuss the lungs for dullness, and auscultate for crackles, diminished or

bronchial breath sounds, and increased vocal fremitus. Look for decreased respiratory excursion. Palpate for lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

bronchial breath sounds, and increased vocal fremitus. Look for decreased respiratory excursion. Palpate for lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.

Diaphoresis is an early sign of certain lifethreatening disorders. These guidelines will help you promptly detect such disorders and intervene to minimize harm to the patient.

Hypoglycemia

If you observe diaphoresis in a patient who complains of blurred vision, ask him about increased irritability and anxiety. Has the patient been unusually hungry lately? Does he have tremors? Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and tachycardia. Then ask about a history of type 2 diabetes or antidiabetic therapy. If you suspect hypoglycemia, evaluate the patient’s blood glucose level using a glucose reagent strip, or send a serum sample to the laboratory. Administer I.V. glucose 50% as ordered to return the patient’s glucose level to normal. Monitor his vital signs and cardiac rhythm. Ensure a patent airway, and be prepared to assist with breathing and circulation, if necessary.

Heatstroke

If you observe profuse diaphoresis in a weak, tired, and apprehensive patient, suspect heatstroke, which can progress to circulatory collapse. Take vital signs, noting a normal or subnormal temperature. Check for ashen gray skin and dilated pupils. Was the patient recently exposed to high temperatures and humidity? Was he wearing heavy clothing or performing strenuous physical activity at the time? Also, ask if he takes a diuretic, which interferes with normal sweating.

Then take the patient to a cool room, remove his clothing, and use a fan to direct cool air over his body. Insert an I.V. catheter, and prepare for electrolyte and fluid replacement. Monitor the patient for signs of shock. Check his urine output carefully along with other sources of output (such as tubes, drains, and ostomies).

Autonomic hyperreflexia

If you observe diaphoresis in a patient with a spinal cord injury above T6 or T7, ask if he has a pounding headache, restlessness, blurred vision, or nasal congestion. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting bradycardia or extremely elevated blood pressure. If you suspect autonomic hyperreflexia, quickly rule out its common complications. Examine the patient for eye pain associated with intraocular hemorrhage and for facial paralysis, slurred speech, or limb weakness associated with intracerebral hemorrhage.

Quickly reposition the patient to remove any pressure stimuli. Also, check for a distended bladder or fecal impaction. Remove any kinks from the urinary catheter if necessary, and administer a suppository or manually remove impacted feces. If you can’t locate and relieve the causative stimulus, start an I.V. catheter. Prepare to administer hydralazine for hypertension.

Myocardial infarction or heart failure

If the diaphoretic patient complains of chest pain and dyspnea, or has arrhythmias or electrocardiogram changes, suspect a myocardial infarction or heart failure. Connect the patient to a cardiac monitor, ensure a patent airway, and administer supplemental oxygen. Start an I.V. catheter, and administer morphine. Be prepared to begin emergency resuscitation if cardiac or respiratory arrest occurs.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Night sweats may be an early feature, occurring either as a manifestation of the disease itself or secondary to an opportunistic infection. The patient also displays fever, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, dramatic and unexplained weight loss, diarrhea, and a persistent cough.

♦ Acromegaly. In this slowly progressive disorder, diaphoresis is a sensitive gauge of disease activity, which involves hypersecretion of growth hormone and increased metabolic rate. The patient has a hulking appearance with an enlarged supraorbital ridge and thickened ears and nose. Other signs and symptoms include warm, oily, thickened skin; enlarged hands, feet, and jaw; joint pain; weight gain; hoarseness; and increased coarse body hair. Increased blood pressure, severe headache, and visual field deficits or blindness may also occur.

♦ Anxiety disorders. Acute anxiety characterizes panic, whereas chronic anxiety characterizes phobias, conversion disorders, obsessions, and compulsions. Whether acute or chronic, anxiety may cause sympathetic stimulation, resulting in diaphoresis. The diaphoresis is most dramatic on the palms, soles, and forehead and is accompanied by palpitations, tachycardia, tachypnea, tremors, and GI distress. Psychological signs and symptoms —fear, difficulty concentrating, and behavior changes—also occur.

♦ Autonomic hyperreflexia. Occurring after resolution of spinal shock in a spinal cord injury above T6, hyperreflexia causes profuse diaphoresis, pounding headache, blurred vision, and dramatically elevated blood pressure. Diaphoresis occurs above the level of the injury, especially on the forehead, and is accompanied by flushing. Other findings include restlessness, nausea, nasal congestion, and bradycardia.

♦ Drug and alcohol withdrawal syndromes. Withdrawal from alcohol or an opioid analgesic may cause generalized diaphoresis, dilated pupils, tachycardia, tremors, and altered mental status (confusion, delusions, hallucinations, agitation). Associated signs and symptoms include severe muscle cramps, generalized paresthesia, tachypnea, increased or decreased blood pressure and, possibly, seizures. Nausea and vomiting are common.

♦ Empyema. Pus accumulation in the pleural space leads to drenching night sweats and fever. The patient also complains of chest pain, cough, and weight loss. Examination reveals decreased respiratory excursion on the affected side and absent or distant breath sounds.

♦ Heart failure. Typically, diaphoresis follows fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, and tachycardia in patients with left-sided heart failure, and jugular vein distention and dry cough in patients with right-sided heart failure. Other features include tachypnea, cyanosis, dependent edema, crackles, ventricular gallop, and anxiety.

♦ Heat exhaustion. Although this condition is marked by failure of heat to dissipate, it initially may cause profuse diaphoresis, fatigue, weakness, and anxiety. These signs and symptoms may progress to circulatory collapse and shock (marked by confusion, thready pulse, hypotension, tachycardia, and cold, clammy skin). Other features include an ashen gray appearance, dilated pupils, and normal or subnormal temperature.

♦ Hodgkin’s disease. Especially in elderly patients, early features of Hodgkin’s disease may include night sweats, fever, fatigue, pruritus, and weight loss. Usually, however, this disease initially causes painless swelling of a cervical lymph node. Occasionally, a Pel-Ebstein fever pattern is present—several days or weeks of fever and chills alternating with afebrile periods with no chills. Systemic signs and symptoms—such as weight loss, fever, and night sweats—indicate a poor prognosis. Progressive lymphadenopathy eventually causes widespread effects, such as hepatomegaly and dyspnea.

♦ Hypoglycemia. Rapidly induced hypoglycemia may cause diaphoresis accompanied by irritability, tremors, hypotension, blurred vision, tachycardia, hunger, and loss of consciousness.

♦ Immunoblastic lymphadenopathy. Resembling Hodgkin’s disease but rarer, this disorder causes episodic diaphoresis along with fever, weight loss, weakness, generalized lymphadenopathy, rash, and hepatosplenomegaly.

♦ Infective endocarditis (subacute). Generalized night sweats occur early in this disorder and are accompanyied by intermittent lowgrade fever, weakness, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and arthralgia. A sudden change in a murmur or the discovery of a new murmur is a classic sign. Petechiae and splinter hemorrhages are also common.

♦ Liver abscess. Signs and symptoms vary, depending on the extent of the abscess, but commonly include diaphoresis, right-upperquadrant pain, weight loss, fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and signs of anemia.

♦ Lung abscess. Drenching night sweats are common in this disorder. Its chief sign, however, is a cough that produces copious amounts of purulent, foul-smelling, and typically bloodtinged sputum. Associated findings include fever with chills, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, weakness, anorexia, weight loss, headache, malaise, clubbing, tubular or amphoric breath sounds, and dullness on percussion.

♦ Malaria. Profuse diaphoresis marks the third stage of paroxysmal malaria, preceded by chills (first stage) and high fever (second stage). Headache, arthralgia, and hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. In the benign form of malaria, these paroxysms alternate with periods of

well-being. The severe form may progress to delirium, seizures, and coma.

well-being. The severe form may progress to delirium, seizures, and coma.

♦ Ménière’s disease. Characterized by severe vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss, this disorder may also cause diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus. Hearing loss may be progressive and tinnitus may persist between attacks.

♦ Myocardial infarction. Diaphoresis usually accompanies acute, substernal, radiating chest pain in this life-threatening disorder. Associated signs and symptoms include anxiety, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, irregular pulse, blood pressure change, fine crackles, pallor, and clammy skin.

♦ Pheochromocytoma. This disorder commonly produces diaphoresis, but its cardinal sign is persistent or paroxysmal hypertension. Other effects include headache, palpitations, tachycardia, anxiety, tremors, pallor, flushing, paresthesia, abdominal pain, tachypnea, nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension.

♦ Pneumonia. In patients with pneumonia, intermittent, generalized diaphoresis accompanies fever, chills, and pleuritic chest pain that increases with deep inspiration. Other features are tachypnea, dyspnea, a productive cough (with scant and mucoid or copious and purulent sputum), headache, fatigue, myalgia, abdominal pain, anorexia, and cyanosis. Auscultation reveals bronchial breath sounds.

♦ Relapsing fever. Profuse diaphoresis marks resolution of the crisis stage of this disorder, which typically produces attacks of high fever accompanied by severe myalgia, headache, arthralgia, diarrhea, vomiting, coughing, and eye or chest pain. Splenomegaly is common, but hepatomegaly and lymphadenopathy may also occur. The patient may develop a transient macular rash. Between 3 and 10 days after onset, the febrile attack abruptly terminates in chills with increased pulse and respiratory rates. Diaphoresis, flushing, and hypotension may then lead to circulatory collapse and death. Relapse invariably occurs if the patient survives the initial attack.

♦ Tetanus. This disorder commonly causes profuse sweating accompanied by low-grade fever, tachycardia, and hyperactive deep tendon reflexes. Early restlessness and pain and stiffness in the jaw, abdomen, and back progress to spasms associated with lockjaw, risus sardonicus, dysphagia, and opisthotonos. Laryngospasm may result in cyanosis or sudden death by asphyxiation.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. This disorder commonly produces diaphoresis accompanied by heat intolerance, weight loss despite increased appetite, tachycardia, palpitations, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, diarrhea, tremors, Plummer’s nails and, possibly, exophthalmos. Gallops may also occur.

♦ Tuberculosis (TB). Although many patients with primary infection are asymptomatic, TB may cause night sweats, low-grade fever, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, and weight loss. In reactivation, a productive cough with mucopurulent sputum, occasional hemoptysis, and chest pain may be present.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Sympathomimetics, certain antipsychotics, thyroid hormone, corticosteroids, and antipyretics may cause diaphoresis. Aspirin and acetaminophen poisoning also cause this sign.

♦ Dumping syndrome. The result of rapid emptying of gastric contents into the small intestine after partial gastrectomy, dumping syndrome causes diaphoresis, palpitations, profound weakness, epigastric distress, nausea, and explosive diarrhea soon after eating.

♦ Envenomation. Depending on the type of bite, neurotoxic effects may include diaphoresis, chills (with or without fever), weakness, dizziness, blurred vision, increased salivation, nausea and vomiting and, possibly, paresthesia and muscle fasciculations. Local features may include ecchymosis and progressively severe pain and edema. Palpation reveals tender regional lymph nodes.

♦ Pesticide poisoning. Among the toxic effects of pesticides are diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blurred vision, miosis, and excessive lacrimation and salivation. The patient may also display fasciculations, muscle weakness, and flaccid paralysis. Signs of respiratory depression and coma may also occur.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

After an episode of diaphoresis, sponge the patient’s face and body and change wet clothes and sheets. To prevent skin irritation, dust skin folds in the groin and axillae and under pendulous breasts with cornstarch, or tuck gauze or cloth into the folds. Encourage regular bathing.

Replace fluids and electrolytes. Regulate infusions of I.V. saline or Ringer’s lactate solution, and monitor urine output. Encourage intake of oral fluids high in electrolytes (such as Gatorade). Enforce bed rest and maintain a quiet

environment. Keep the patient’s room temperature moderate to prevent additional diaphoresis.

environment. Keep the patient’s room temperature moderate to prevent additional diaphoresis.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood tests, cultures, chest X-rays, immunologic studies, biopsy, computed tomography scan, and audiometry. Monitor the patient’s vital signs, including temperature.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Diaphoresis in children commonly results from environmental heat or overdressing the child; it’s usually most apparent around the head. Other causes include drug withdrawal associated with maternal addiction, heart failure, thyrotoxicosis, and the effects of such drugs as antihistamines, ephedrine, haloperidol, and thyroid hormone.

Assess fluid status carefully. Some fluid loss through diaphoresis may precipitate hypovolemia more rapidly in a child than an adult. Monitor input and output, weigh the child daily, and note the duration of each episode of diaphoresis.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

Elderly patients with TB may exhibit a change in activity or weight rather than the hallmark symptoms of fever and night sweats. Also, keep in mind that older patients may not exhibit diaphoresis because of a decreased sweating mechanism. For this reason, they’re at increased risk for developing heatstroke in high temperatures.

Diarrhea

Usually a chief sign of an intestinal disorder, diarrhea is an increase in the volume of stools compared with the patient’s normal bowel elimination habits. It varies in severity and may be acute or chronic. Acute diarrhea may result from acute infection, stress, fecal impaction, or the effect of a drug. Chronic diarrhea may result from chronic infection, obstructive and inflammatory bowel disease, malabsorption syndrome, an endocrine disorder, or GI surgery. Periodic diarrhea may result from food intolerance or from ingestion of spicy or high-fiber foods or caffeine.

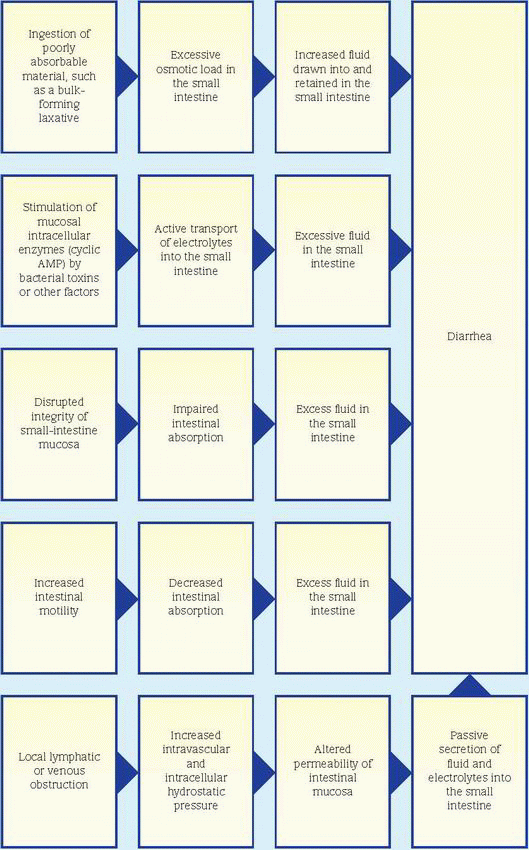

One or more pathophysiologic mechanisms may contribute to diarrhea. (See What causes diarrhea, page 214.) The fluid and electrolyte imbalances it produces may precipitate lifethreatening arrhythmias or hypovolemic shock.

If the patient’s diarrhea is profuse, check for signs of shock—tachycardia, hypotension, and cool, pale, clammy skin. If you detect these signs, place the patient in the supine position and elevate his legs 20 degrees. Insert an I.V. catheter for fluid replacement. Monitor the patient for electrolyte imbalances, and look for an irregular pulse, muscle weakness, anorexia, and nausea and vomiting. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment handy.

If the patient’s diarrhea is profuse, check for signs of shock—tachycardia, hypotension, and cool, pale, clammy skin. If you detect these signs, place the patient in the supine position and elevate his legs 20 degrees. Insert an I.V. catheter for fluid replacement. Monitor the patient for electrolyte imbalances, and look for an irregular pulse, muscle weakness, anorexia, and nausea and vomiting. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment handy.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient isn’t in shock, proceed with a brief physical examination. Evaluate hydration, check skin turgor and mucous membranes, and take blood pressure with the patient lying, sitting, and standing. Inspect the abdomen for distention, and palpate for tenderness. Auscultate bowel sounds. Check for tympany over the abdomen. Take the patient’s temperature, and note any chills. Also, look for a rash. Conduct a rectal examination and a pelvic examination if indicated.

Explore signs and symptoms associated with diarrhea. Does the patient have abdominal pain and cramps? Difficulty breathing? Is he weak or fatigued? Find out his drug history. Has he had GI surgery or radiation therapy recently? Ask the patient to briefly describe his diet. Does he have any known food allergies? Lastly, find out if he’s under unusual stress.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Anthrax, GI. This disease follows ingestion of contaminated meat from an animal infected with Bacillus anthracis. Early signs and symptoms include decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Later signs and symptoms include severe bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and hematemesis.

♦ Carcinoid syndrome. In this disorder, severe diarrhea occurs with flushing—usually of the head and neck—that’s commonly caused by emotional stimuli or the ingestion of food, hot water, or alcohol. Associated signs and symptoms include abdominal cramps, dyspnea, anorexia, weight loss, weakness, palpitations, valvular heart disease, and depression.

♦ Cholera. After ingesting water or food contaminated by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the patient experiences abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting. Other signs and symptoms include thirst (due to severe water and electrolyte loss), weakness, muscle cramps, decreased skin turgor, oliguria, tachycardia, and hypotension.

Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

Without treatment, death can occur within hours.

♦ Clostridium difficile infection. The patient may be asymptomatic or may have soft, unformed stools or watery diarrhea that may be foul smelling or grossly bloody; abdominal pain, cramping, and tenderness; fever; and a white blood cell count as high as 20,000/µl. In severe cases, the patient may develop toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, or peritonitis.

♦ Crohn’s disease. This recurring inflammatory disorder produces diarrhea, abdominal pain with guarding and tenderness, and nausea. The patient may also display fever, chills, weakness, anorexia, and weight loss.

♦ Escherichia coli O157:H7. Watery or bloody diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal cramps occur after the patient eats undercooked beef or other foods contaminated with this particular strain of bacteria. Hemolytic uremic syndrome, which causes red blood cell destruction and eventually acute renal failure, is a complication of E. coli O157:H7 in children age 5 and younger and elderly people.

♦ Infections. Acute viral, bacterial, and protozoal infections (such as cryptosporidiosis) cause the sudden onset of watery diarrhea as well as abdominal pain or cramps, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Significant fluid and electrolyte loss may cause signs of dehydration and shock. Chronic tuberculosis and fungal and parasitic infections may produce a less severe but more persistent diarrhea, accompanied by epigastric distress, vomiting, weight loss and, possibly, passage of blood and mucus.

♦ Intestinal obstruction. Partial intestinal obstruction increases intestinal motility, resulting in diarrhea, abdominal pain with tenderness and guarding, nausea and, possibly, distention.

♦ Irritable bowel syndrome. Diarrhea alternates with constipation or normal bowel function. Related findings include abdominal pain, tenderness, and distention; dyspepsia; and nausea.

♦ Ischemic bowel disease. This lifethreatening disorder causes bloody diarrhea with abdominal pain. If severe, shock may occur, requiring surgery.

♦ Lactose intolerance. Diarrhea occurs within several hours of ingesting milk or milk products in patients with this disorder. It’s accompanied by cramps, abdominal pain, borborygmi, bloating, nausea, and flatus.

♦ Large-bowel cancer. In this disorder, bloody diarrhea is seen with a partial obstruction. Other signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, weakness, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and depression.

♦ Listeriosis. This infection, caused by ingestion of food contaminated with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, primarily affects pregnant women, neonates, and those with weakened immune systems. Characteristic findings include diarrhea, fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Fever, headache, nuchal rigidity, and altered level of consciousness may occur if the infection spreads to the nervous system and causes meningitis.

Listeriosis during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Listeriosis during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.♦ Malabsorption syndrome. Occurring after meals, diarrhea is accompanied by steatorrhea, abdominal distention, and muscle cramps. The patient also displays anorexia, weight loss, bone pain, anemia, weakness, and fatigue. He may bruise easily and have night blindness.

♦ Pseudomembranous enterocolitis. This potentially life-threatening disorder commonly follows antibiotic administration. It produces copious watery, green, foul-smelling, bloody diarrhea that rapidly precipitates signs of shock. Other signs and symptoms include colicky abdominal pain, distention, fever, and dehydration.

♦ Q fever. This infection is caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii and causes diarrhea along with fever, chills, severe headache, malaise, chest pain, and vomiting. In severe cases, hepatitis or pneumonia may follow.

♦ Rotavirus gastroenteritis. This disorder commonly starts with a fever, nausea, and vomiting, followed by diarrhea. The illness can be mild to severe and last from 3 to 9 days. Diarrhea and vomiting may result in dehydration.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. In this disorder, diarrhea is accompanied by nervousness, tremors, diaphoresis, weight loss despite increased appetite, dyspnea, palpitations, tachycardia, enlarged thyroid, heat intolerance and, possibly, exophthalmos.

♦ Ulcerative colitis. The hallmark of this disorder is recurrent bloody diarrhea with pus or mucus. Other signs and symptoms include tenesmus, hyperactive bowel sounds, cramping

lower abdominal pain, low-grade fever, anorexia and, possibly, nausea and vomiting. Weight loss, anemia, and weakness are late findings.

lower abdominal pain, low-grade fever, anorexia and, possibly, nausea and vomiting. Weight loss, anemia, and weakness are late findings.

♦ Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) infection. Enterococci are bacteria naturally present in the intestinal tract of all people; however, some strains of enterococci have become resistant to vancomycin. Serious VRE infections may occur in hospitalized patients with such comorbidities as cancer, kidney disease, or immune deficiencies. Elderly patients and those hospitalized for long periods are also at risk for developing VRE infections. Symptoms of VRE infection depend on where the infection is; patients with VRE infections may have diarrhea, fever, and fatigue.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Drugs. Many antibiotics—such as ampicillin, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, and clindamycin— cause diarrhea. Other drugs that may cause diarrhea include magnesium-containing antacids, lactulose, dantrolene, ethacrynic acid, mefenamic acid, methotrexate, metyrosine and, with high doses, cardiac glycosides and quinidine. Laxative abuse can cause acute or chronic diarrhea.

♦ Foods. Foods that contain certain oils may inhibit the food’s absorption, causing acute uncontrollable diarrhea and rectal leakage.

♦ Lead poisoning. Alternating diarrhea and constipation may be accompanied by abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. The patient complains of a metallic taste, headache, and dizziness and displays a bluish gingival lead line.

♦ Treatments. Gastrectomy, gastroenterostomy, and pyloroplasty may produce diarrhea. High-dose radiation therapy may produce enteritis associated with diarrhea.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

When appropriate, administer an analgesic for pain and an opiate as ordered to decrease intestinal motility, unless the patient may have a stool infection. Ensure the patient’s privacy during defecation, and empty bedpans promptly. Clean the perineum thoroughly, and apply ointment to prevent skin breakdown. Quantify the amount of liquid stool and carefully observe intake and output.

Stress the need for medical follow-up to patients with inflammatory bowel disease (particularly ulcerative colitis), who have an increased risk of developing colon cancer.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Diarrhea in children commonly results from infection, although chronic diarrhea may result from malabsorption syndrome, an anatomic defect, or allergies. Because dehydration and electrolyte imbalance occur rapidly in children, diarrhea can be life-threatening. Diligently monitor all episodes of diarrhea, and replace lost fluids immediately.

GERIATRIC POINTERS

In the elderly patient with new-onset segmental colitis, always consider ischemia before labeling the patient as having Crohn’s disease.

PATIENT COUNSELING

Explain the purpose of diagnostic tests to the patient. These tests may include blood studies, stool cultures, X-rays, and endoscopy.

Administer I.V. fluid replacements to help the patient maintain adequate hydration. Measure liquid stools and weigh the patient daily. Monitor electrolyte levels and hematocrit.

Advise the patient to avoid spicy or high-fiber foods (such as fruits), caffeine, high-fat foods, and milk. Suggest smaller, more frequent meals if he has had GI surgery or disease. If appropriate, teach the patient stress-reducing measures, such as guided imagery and deep-breathing techniques, or recommend counseling.

Diplopia

Diplopia is double vision—seeing one object as two. This symptom results when extraocular muscles fail to work together, causing images to fall on noncorresponding parts of the retinas. What causes this muscle incoordination? Orbital lesions, the effects of surgery, or impaired function of the cranial nerves (CNs) that supply extraocular muscles—oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducens (CN VI)— may be responsible. (See Testing extraocular muscles.)

Diplopia usually begins intermittently and affects near or far vision exclusively. It can be classified as monocular or binocular. More common binocular diplopia may result from ocular deviation or displacement, extraocular muscle palsies, or psychoneurosis, or it may occur after retinal surgery. Monocular diplopia

may result from an early cataract, retinal edema or scarring, iridodialysis, a subluxated lens, a poorly fitting contact lens, or an uncorrected refractive error such as astigmatism. Diplopia may also occur in hysteria or malingering.

may result from an early cataract, retinal edema or scarring, iridodialysis, a subluxated lens, a poorly fitting contact lens, or an uncorrected refractive error such as astigmatism. Diplopia may also occur in hysteria or malingering.

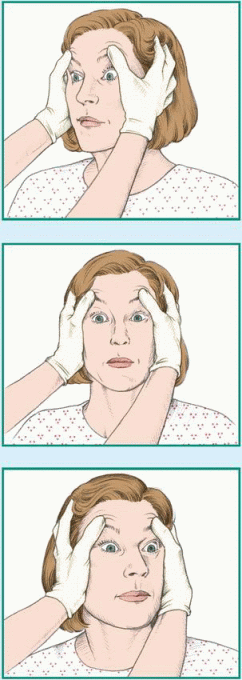

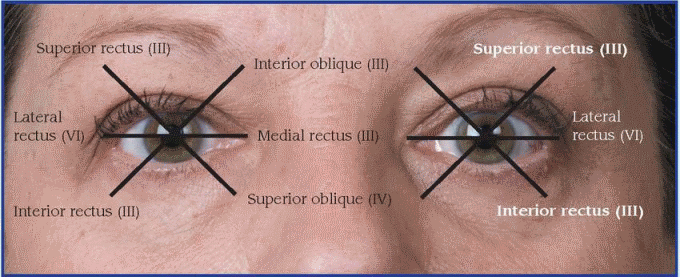

Testing extraocular muscles

The coordinated action of six muscles controls eyeball movements. To test the function of each muscle and the cranial nerve that innervates it, ask the patient to look in the direction controlled by that muscle. The six directions you can test make up the cardinal fields of gaze. The patient’s inability to turn the eye in the designated direction indicates muscle weakness or paralysis.

|

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

If the patient complains of double vision, first check his neurologic status. Evaluate his level of consciousness (LOC); pupil size, equality, and response to light; and motor and sensory function. Then take his vital signs. Briefly ask about associated symptoms. First find out about associated neurologic symptoms, especially a severe headache, because diplopia can accompany serious disorders.

Next, continue with a more detailed examination. Find out when the patient first noticed diplopia. Are the images side by side (horizontal), one above the other (vertical), or a combination? Does diplopia affect near or far vision? Does it affect certain directions of gaze? Ask if diplopia has worsened, remained the same, or subsided. Does its severity change throughout the day? Diplopia that worsens or appears in the evening may indicate myasthenia gravis. Find out if the patient can correct diplopia by tilting his head. If so, ask him to show you. (If the patient has a fourth cranial nerve lesion, tilting the head toward the opposite shoulder causes compensatory tilting of the unaffected eye. If he has incomplete sixth cranial nerve palsy, tilting the head toward the side of the paralyzed muscle may relax the affected lateral rectus muscle.)

Explore associated symptoms such as eye pain. Ask about hypertension, diabetes mellitus, allergies, and thyroid, neurologic, or muscular disorders. Also, note a history of extraocular muscle disorders, trauma, or eye surgery.

Observe the patient for ocular deviation, ptosis, exophthalmos, eyelid edema, and conjunctival injection. Distinguish monocular from binocular diplopia by asking the patient to occlude one eye at a time. If he still sees double out of one eye, he has monocular diplopia. Test visual acuity and extraocular muscles. Also, check vital signs.

MEDICAL CAUSES

♦ Alcohol intoxication. Diplopia, a common symptom of this disorder, may be accompanied by confusion, slurred speech, halitosis, staggering gait, behavior changes, nausea, vomiting and, possibly, conjunctival injection.

♦ Botulism. The hallmark signs of botulism are diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and ptosis. Early findings include dry mouth, sore throat, vomiting, and diarrhea. Later, descending weakness or paralysis of extremity and trunk muscles causes hyporeflexia and dyspnea.

♦ Brain tumor. Diplopia may be an early symptom of a brain tumor. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the tumor’s size and location but may include eye deviation, emotional lability, decreased LOC, headache, vomiting, absence or generalized tonic-clonic seizures, hearing loss, visual field deficits, abnormal pupillary responses, nystagmus, motor weakness, and paralysis.

♦ Cavernous sinus thrombosis. This disorder may produce diplopia and limited eye movement. Associated signs and symptoms include exophthalmos, orbital and eyelid edema, diminished or absent pupillary responses, impaired visual acuity, papilledema, and fever.

♦ Diabetes mellitus. Among the long-term effects of this disorder may be diplopia due to isolated third cranial nerve palsy. Diplopia typically begins suddenly and may be accompanied by pain.

♦ Encephalitis. Initially, this disorder may cause a brief episode of diplopia and eye deviation. However, it usually begins with sudden onset of high fever, severe headache, and vomiting. As the inflammation progresses, the patient may display signs of meningeal irritation, decreased LOC, seizures, ataxia, and paralysis.

♦ Head injury. Potentially life-threatening head injuries may cause diplopia, depending on the site and extent of the injury. Associated signs and symptoms include eye deviation, pupillary changes, headache, decreased LOC, altered vital signs, nausea, vomiting, and motor weakness or paralysis.

♦ Intracranial aneurysm. This life-threatening disorder initially produces diplopia and eye deviation, perhaps accompanied by ptosis and a dilated pupil on the affected side. The patient complains of a recurrent, severe, unilateral, frontal headache. After the aneurysm ruptures, the headache becomes violent. Associated signs and symptoms include neck and spinal pain and rigidity, decreased LOC, tinnitus, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and unilateral muscle weakness or paralysis.

♦ Multiple sclerosis (MS). Diplopia, a common early symptom of MS, is usually accompanied by blurred vision and paresthesia. As MS progresses, signs and symptoms may include nystagmus, constipation, muscle weakness, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, gait ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, impotence, emotional lability, and urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence.

♦ Myasthenia gravis. This disorder initially produces diplopia and ptosis, which worsen throughout the day. It then progressively involves other muscles, resulting in blank facial expression; nasal voice; difficulty chewing, swallowing, and making fine hand movements and, possibly, signs of life-threatening respiratory muscle weakness.

♦ Ophthalmologic migraine. Most common in young adults, this disorder results in diplopia that persists for days after the headache resolves. Accompanying signs and symptoms include severe unilateral pain, ptosis, and extraocular muscle palsies. Irritability, depression, or slight confusion may also occur.

♦ Orbital blowout fracture. This fracture usually causes monocular diplopia affecting the upward gaze. However, with marked periorbital edema, diplopia may affect other directions of gaze. This fracture commonly causes periorbital ecchymosis but doesn’t affect visual acuity, although eyelid edema may prevent accurate testing. Subcutaneous crepitation of the eyelid and orbit is typical. Occasionally, the patient’s pupil is dilated and unreactive, and he may have a hyphema.

♦ Orbital cellulitis. Inflammation of the orbital tissues and eyelids causes sudden diplopia as well as eye deviation and pain, purulent drainage, eyelid edema, chemosis and redness, exophthalmos, nausea, and fever.

♦ Orbital tumor. An enlarging tumor can cause diplopia, exophthalmos and, possibly, blurred vision.

♦ Stroke. Diplopia characterizes this lifethreatening disorder when it affects the vertebrobasilar artery. Other signs and symptoms include unilateral motor weakness or paralysis, ataxia, decreased LOC, dizziness, aphasia, visual field deficits, circumoral numbness, slurred speech, dysphagia, and amnesia.

♦ Thyrotoxicosis. Diplopia occurs when exophthalmos characterizes the disorder. It usually begins in the upper field of gaze because of infiltrative myopathy involving the inferior rectus muscle. It’s accompanied by impaired eye movement, excessive tearing, eyelid edema and, possibly, inability to close the eyelids. Other cardinal findings include tachycardia, palpitations, weight loss, diarrhea, tremors, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, diaphoresis, and heat intolerance.

OTHER CAUSES

♦ Eye surgery. Fibrosis associated with eye surgery may restrict eye movement, resulting in diplopia.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Continue to monitor vital signs and neurologic status if you suspect an acute neurologic disorder. Prepare the patient for neurologic tests such as a computed tomography scan. Provide a safe environment. If the patient has severe diplopia, remove sharp obstacles and assist him with ambulation. Also, institute seizure precautions if indicated.

PEDIATRIC POINTERS

Strabismus, which can be congenital or acquired at an early age, produces diplopia; however, diplopia is a rare complaint in young children because the brain rapidly compensates for double vision by suppressing one image. School-age children who complain of double vision require a careful examination to rule out serious disorders such as a brain tumor.

Dizziness

A common symptom, dizziness is a sensation of imbalance or faintness, sometimes associated with giddiness, weakness, confusion, and blurred or double vision. Episodes of dizziness are usually brief; they may be mild or severe with an abrupt or gradual onset. Dizziness may be aggravated by standing up quickly and alleviated by lying down and by rest.

Dizziness typically results from inadequate blood flow and oxygen supply to the cerebrum and spinal cord. It’s a key symptom in certain serious disorders, such as hypertension and vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency, and it may also occur in anxiety, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders, and postconcussion syndrome.

Dizziness is commonly confused with vertigo—a sensation of revolving in space or of surroundings revolving around oneself. However, unlike dizziness, vertigo is commonly accompanied by nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, staggering gait, and tinnitus or hearing loss. Dizziness and vertigo may occur together, as in postconcussion syndrome.

If the patient complains of dizziness, first ensure his safety by preventing falls, and then determine the severity and onset of the dizziness. Ask the patient to describe it. Is it associated with headache or blurred vision? Next, take the patient’s blood pressure while he’s lying, sitting, and standing to check for orthostatic hypotension. Ask about a history of high blood pressure. Determine if the patient is at risk for hypoglycemia. Tell the patient to lie down, and recheck his vital signs every 15 minutes. Insert an I.V. catheter, and prepare to administer medications as ordered.

If the patient complains of dizziness, first ensure his safety by preventing falls, and then determine the severity and onset of the dizziness. Ask the patient to describe it. Is it associated with headache or blurred vision? Next, take the patient’s blood pressure while he’s lying, sitting, and standing to check for orthostatic hypotension. Ask about a history of high blood pressure. Determine if the patient is at risk for hypoglycemia. Tell the patient to lie down, and recheck his vital signs every 15 minutes. Insert an I.V. catheter, and prepare to administer medications as ordered.HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Ask about a history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Is the patient taking drugs prescribed for high blood pressure? If so, when did he take his last dose?

If the patient’s blood pressure is normal, obtain a more complete history. Ask if he’s had a myocardial infarction, heart failure, kidney disease, or atherosclerosis, which may predispose him to cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, and a transient ischemic attack. Does he have a history of anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anxiety disorders, or head injury? Obtain a complete drug history.