Features

ThinPrep® (TP)

SurePath™ (SP)

Conventional preparation (CP)

Sample collection

Uniform – head of sampling device is discarded

Uniform – head of sampling device is submitted

Uniform – head of sampling device is discarded

Slide preparation

Fully automated

Partially automated

Manual

Number of cells

~50,000

~50,000

~300,000

Slide area

Cells in well-defined 20 mm diameter area

Cells in well-defined 13 mm diameter area

Cells diffusely smeared in 25 × 75 mm area

Image-guided screening

ThinPrep® Imaging System

FocalPoint™ Slide Profiler and FocalPoint Guided Screener

FocalPoint Slide Profiler and FocalPoint Guided Screener

Fixation

Methanol

Ethanol

Alcohol

Cell preservation

Good

Good

Variable

Obscuring factors

None

None

Usually present

Air-drying

None

None

Usually present

HPV testing

Testing from vial (FDA approved)

Testing from vial (not FDA approved but can be validated)

Testing from another sample

Meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials demonstrated no significant difference between CP and LBC in the detection of CIN2/3 lesions

LBC offers a “cleaner” and possibly more efficient cell preparation to review and the ability to perform human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, as well as chlamydia and gonorrhea testing

♦

Both LBC methods have developed location-guided imaging systems designed to present the cytotechnologist with the fields of vision most likely to harbor abnormal cells:

ThinPrep® Imaging System: 22 fields of vision

BD FocalPoint™ Guided Screening Imaging System: 10 fields of vision

The 2014 Bethesda System

Specimen Type

♦

Indicate conventional smear (Pap smear) and liquid-based preparation (Pap test) versus others

Specimen Adequacy

♦

Satisfactory for evaluation (describe presence or absence of endocervical/transformation zone component and any other quality indicators, e.g., partially obscuring blood, inflammation, etc)

♦

Unsatisfactory for evaluation (specify reason)

Specimen rejected/not processed (specify reason)

Specimen processed and examined, but unsatisfactory for evaluation of epithelial abnormality because of (specify reason)

General Categorization (Optional)

Negative for Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy

♦

Others: see “Interpretation/Result” (e.g., endometrial cells in a woman aged 45 years or older)

♦

Epithelial cell abnormality: see “Interpretation/Result” (specify “squamous” or “glandular,” as appropriate)

Interpretation/Result

Negative for Intraepithelial Lesion or Malignancy

♦

(When there is no cellular evidence of neoplasia, state this in the general categorization above and/or in the “Interpretation/Result” of the report – whether or not there are organisms or other nonneoplastic findings)

Nonneoplastic Findings (Optional to Report)

♦

Nonneoplastic cellular variations

Squamous metaplasia

Keratotic changes

Tubal metaplasia

Atrophy

Pregnancy-associated changes

♦

Reactive cellular changes associated with:

Inflammation (includes typical repair)

Lymphocytic (follicular) cervicitis

Radiation

Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD)

Glandular cells status post-hysterectomy

Organisms

♦

Trichomonas vaginalis

♦

Fungal organisms morphologically consistent with Candida spp

♦

Shift in flora suggestive of bacterial vaginosis

♦

Bacteria morphologically consistent with Actinomyces spp

♦

Cellular changes consistent with herpes simplex virus

♦

Cellular changes consistent with cytomegalovirus

Others

♦

Endometrial cells (in a woman aged 45 years or older)

(Also specify if “negative for squamous intraepithelial lesion”)

Epithelial Cell Abnormalities

♦

Squamous cell

Atypical squamous cells

Of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

Cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

♦

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) (encompassing: HPV/mild dysplasia/CIN-1)

♦

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) (encompassing: moderate and severe dysplasia, CIS; CIN-2 and CIN-3)

With features suspicious for invasion (if invasion is suspected)

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma

♦

Glandular cell

Atypical

Endocervical cells (NOS or specify in comments)

Endometrial cells (NOS or specify in comments)

Glandular cells (NOS or specify in comments)

Atypical

Endocervical cells, favor neoplastic

Glandular cells, favor neoplastic

♦

Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ

Adenocarcinoma

Endocervical

Endometrial

Extrauterine

Not otherwise specified (NOS)

Other Malignant Neoplasms (Specify)

Adjunctive Testing

♦

Provide a brief description of the test method(s) and report the result so that it is easily understood by the clinician

♦

Such as small cell carcinoma, papillary serous adenocarcinoma, extrauterine metastatic adenocarcinoma, malignant mixed mullerian tumor, lymphoma, etc

Computer-Assisted Interpretation of Cervical Cytology

♦

If case is examined by an automated device, specify the device and result

Educational Notes and Comments Appended to Cytology Reports (Optional)

♦

Suggestions should be concise and consistent with clinical follow-up guidelines published by professional organizations (references to relevant publications may be included)

♦

Abbreviation: CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; CIS, carcinoma in situ; HPV, human papillomavirus; NOS, not otherwise specified; Pap, Papanicolaou

Specimen Adequacy Terminology and Reporting

Adequacy

♦

An adequate cervical Pap test has an estimated minimum of 8,000–12,000 well-visualized and well-preserved squamous cells for conventional preparations (CP) and 5,000 for liquid-based cytology (LBC). The minimum number of squamous cells required for vaginal Pap tests or Pap tests in patients with a history of radiation therapy is 2,000 cells

This minimum cell range should be an estimate aided by published diagrams of representations of microscopic fields with different parameters of microscope objectives/oculars/field number and number of cells

♦

Any specimen with abnormal cells is by definition satisfactory for evaluation regardless of number of cells

♦

Possible quality indicators might include: absence of pertinent clinical information (such as date of last menstrual period, age, etc.), air-drying, poor preservation of cellular material, excessive blood/mucous/exudates, thick cell groups, scant cellularity, or excessive cytolysis

Endocervical/Transformation Zone Component (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2)

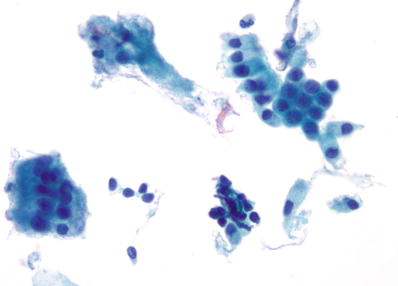

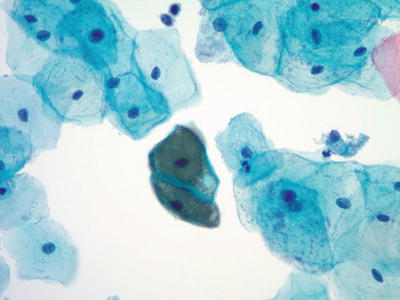

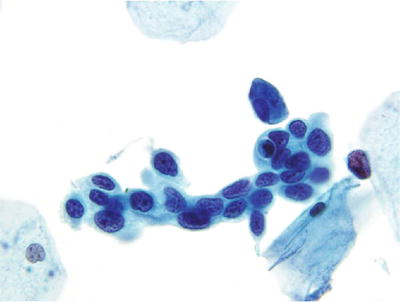

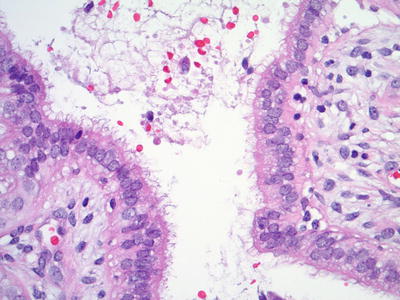

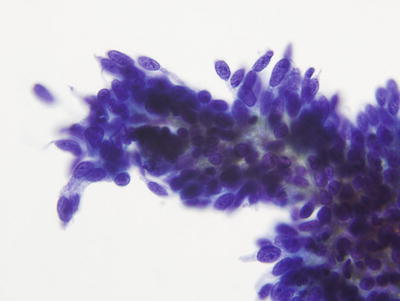

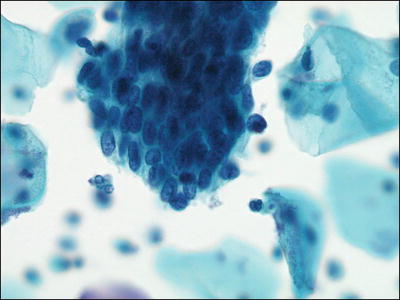

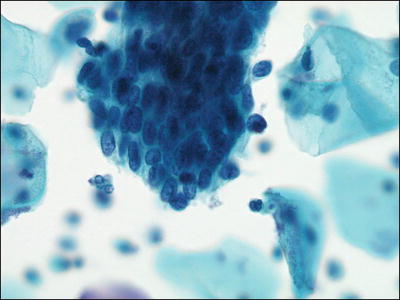

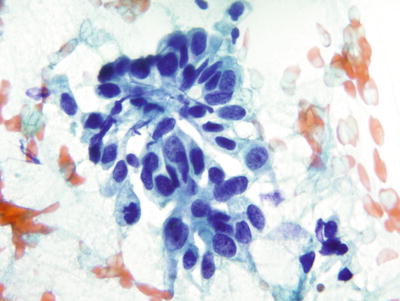

Fig. 1.1.

Satisfactory for evaluation . Endocervical/transformation zone component present. Normal endocervical cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

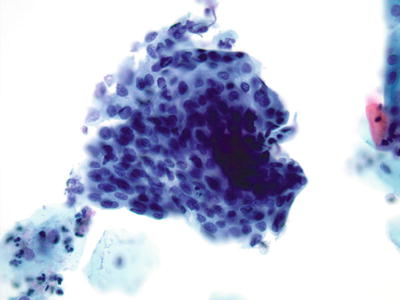

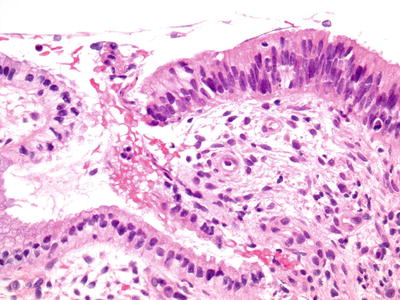

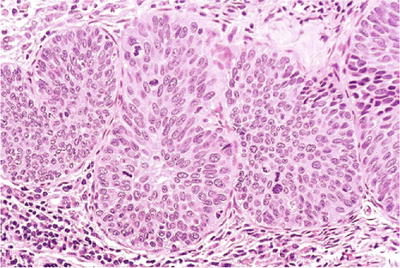

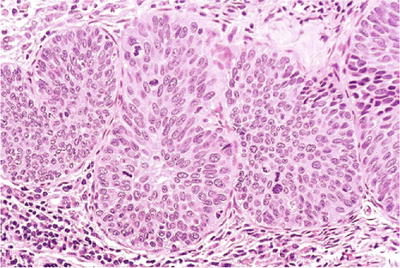

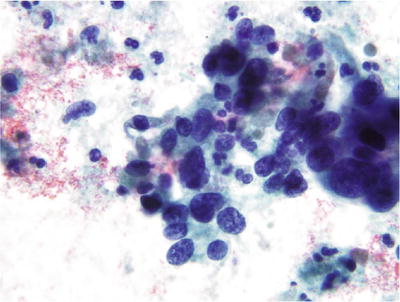

Fig. 1.2.

Satisfactory for evaluation. Endocervical/transformation zone component present. Immature and mature metaplastic cells. CP conventional preparation.

♦

At least 10 well-preserved endocervical and/or squamous metaplastic cells should be observed to report that the endocervical/transformation zone (EC/TZ) was sampled

♦

The presence or absence of EC/TZ component and any other quality indicators should be listed immediately after satisfactory statement based on the above adequacy criteria

♦

According to the 2012 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) management guidelines, women with negative cytology with an absent or insufficient EC/TZ do not necessarily require early repeat testing, especially if the patient has a negative Pap test history:

For women 21–29 years old, routine screening is recommended

For women 30 years or older with no HPV test result, HPV testing is preferred. If HPV test is negative, return to routine screening is recommended. If HPV test is positive, repeat both tests in 1 year. Genotyping for HPV 16/18 is also acceptable. If HPV 16/18 is positive, colposcopy is recommended, and if HPV 16/18 is absent, repeat co-testing in 1 year is recommended

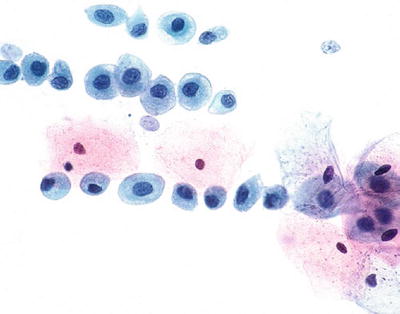

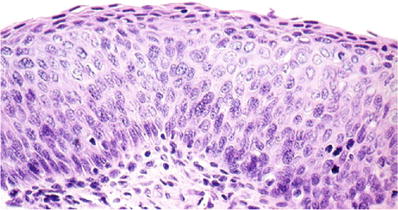

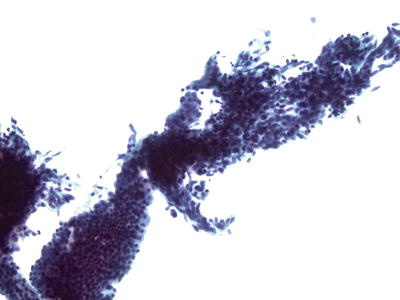

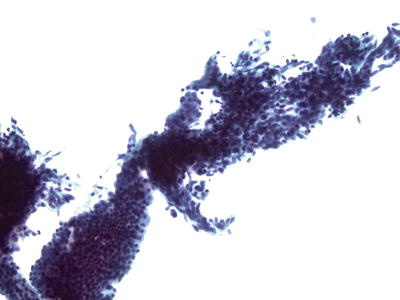

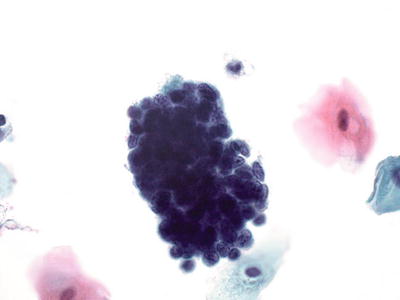

Unsatisfactory Specimen (Fig. 1.3)

Fig. 1.3.

Unsatisfactory for evaluation, obscuring exudate. The specimen is totally obscured by acute inflammatory cells precluding evaluation. Greater than 75% obscuring is considered unsatisfactory if no abnormal cells are identified. CP conventional preparation.

♦

Clarify the laboratory’s role in processing and evaluation of the specimen in the report

Suggested wording to clarify report:

Specimen rejected (not processed) because of the following: specimen not labeled, slide broken, etc

Specimen processed and examined, but is unsatisfactory for evaluation of epithelial abnormality because of obscuring blood, inflammation (greater than 75% of the cells are obscured), etc

♦

Additional comments or recommendations may be suggested as appropriate

Suggested wording to clarify report:

An excessively bloody or inflamed Pap test may hinder the screener’s ability to detect an underlying abnormality and a repeat examination/evaluation is suggested

♦

For LBC specimens that are heavily contaminated with blood, glacial acetic acid (GAA) is employed in order to lyse red blood cells and facilitate interpretation:

Most studies have shown that GAA pretreatment has little effect on commercial HPV tests

♦

Lubricants containing carboners can significantly decrease specimen adequacy and should be avoided when collecting LBC Pap tests. An unusual increase in unsatisfactory Pap tests should warrant notification of the clinicians to determine the cause and whether there has been a change in lubricant

♦

Low squamous cellularity is the most common cause of unsatisfactory Pap tests. Most of these patients are elderly and many have a history of cancer treatment or hysterectomy

♦

A significantly high abnormal follow-up rate is observed in patients with unsatisfactory Pap tests, emphasizing the importance of identifying and following these patients as recommended

♦

The ASCCP 2012 management guidelines:

For an unsatisfactory cytology result and no, unknown, or negative HPV test result, repeat cytology in 2–4 months is recommended. Triage using HPV testing is not recommended

Treatment to resolve atrophy or obscuring inflammation when a known etiology is present is acceptable

For women 30 years or older, with unsatisfactory Pap test and a positive co-tested HPV result, repeat cytology in 2–4 months or colposcopy is acceptable

Colposcopy is recommended for women with two consecutive unsatisfactory Pap tests

Organisms

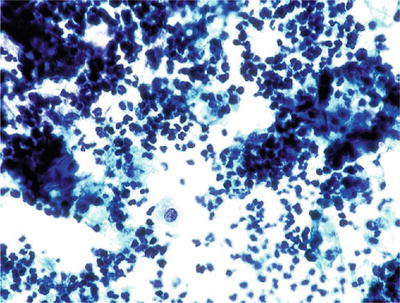

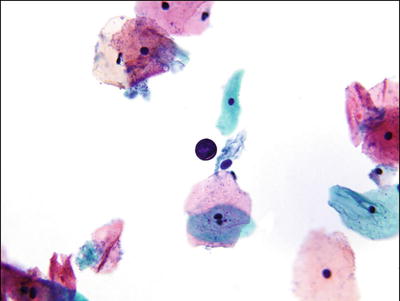

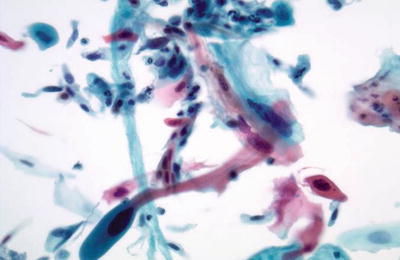

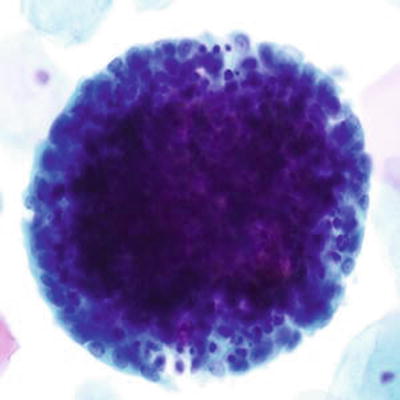

Trichomonas vaginalis (Fig. 1.4)

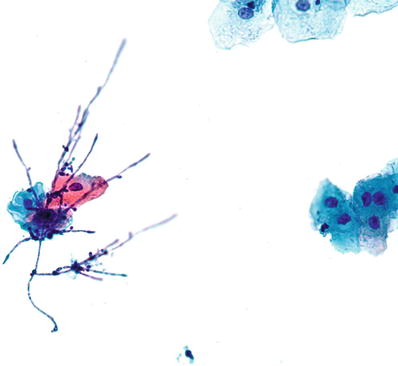

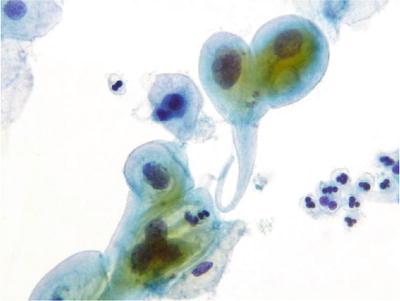

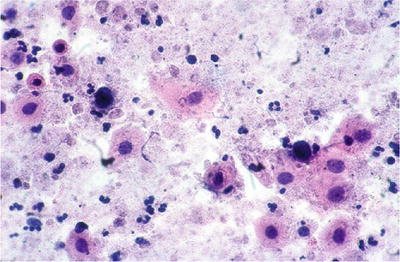

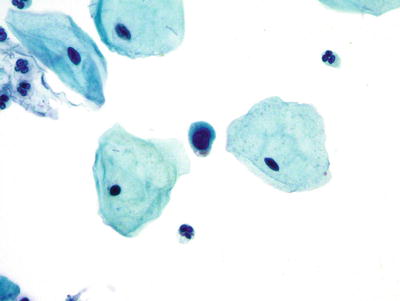

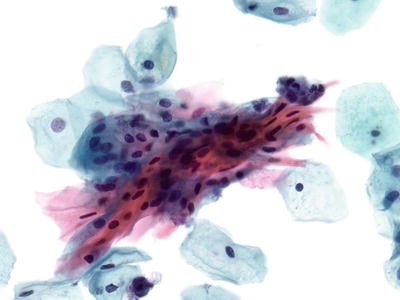

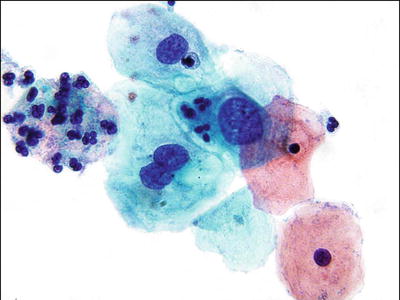

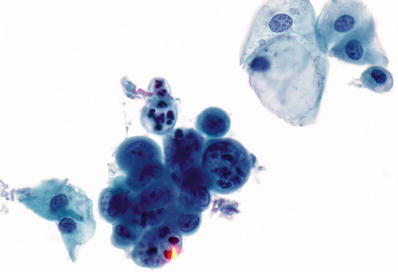

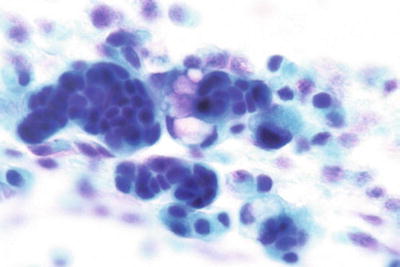

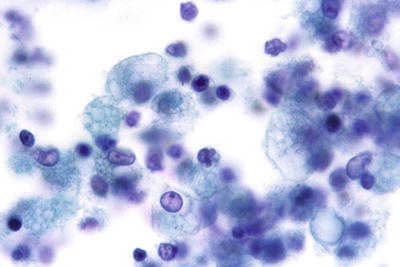

Fig. 1.4.

Trichomonas vaginalis . Pear-shaped organisms with eccentrically located nucleus and granular cytoplasm. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Approximately 25% of women are carriers of Trichomonas vaginalis. Trichomonas vaginalis often coexists with Leptothrix and other coccoid bacteria. The organisms are small, “pear or kite-shaped,” and faintly stained with small, oval, eccentric, and pale nuclei and red cytoplasmic granules. Rare flagella may be observed in LBC. “Cannonballs” representing adherence of neutrophils to squamous cells may be observed. The squamous cells may show reactive small perinuclear clearing and cytoplasmic vacuolization, polychromasia, or a “moth-eaten” appearance. Granular debris and inflammation are usually present in the background

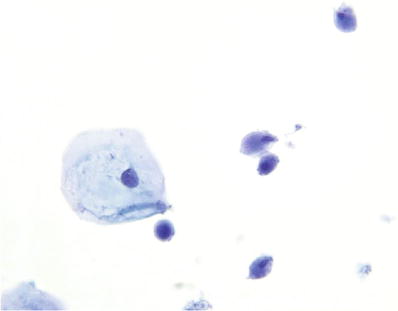

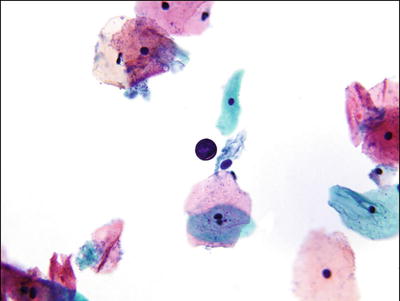

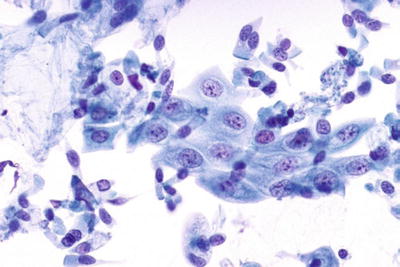

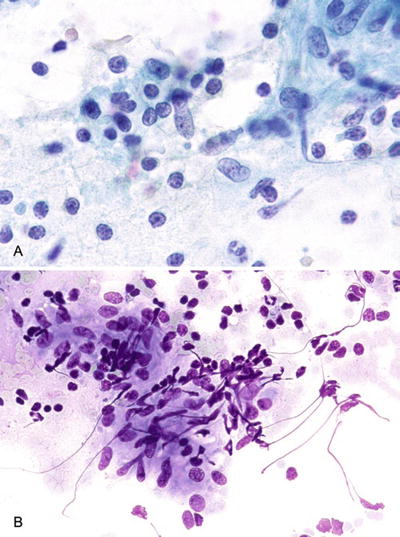

Fungal Organisms Morphologically Consistent with Candida Species (Fig. 1.5)

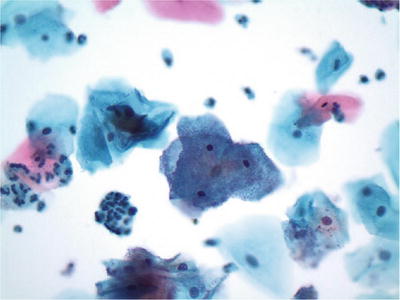

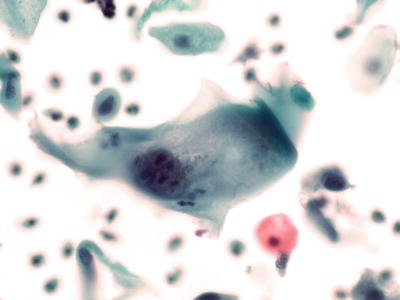

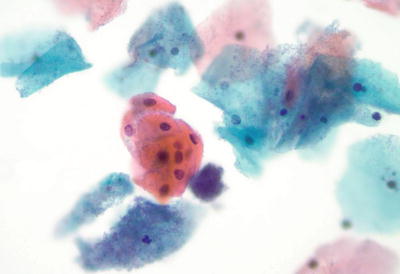

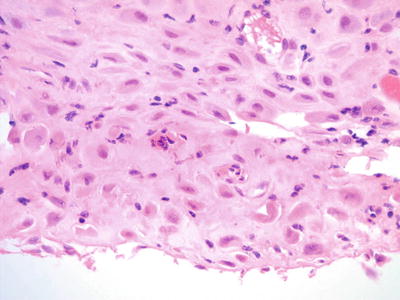

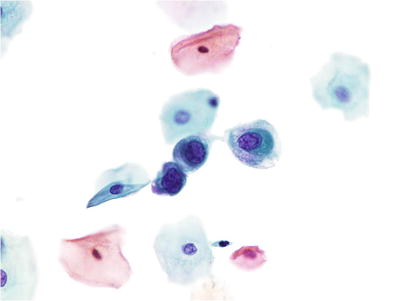

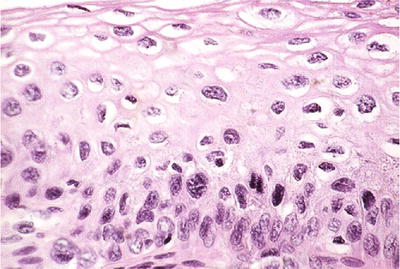

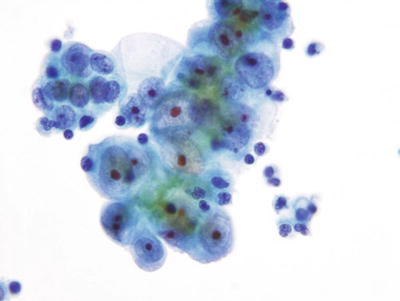

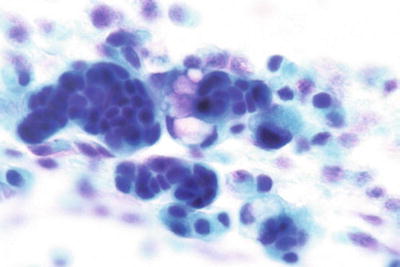

Fig. 1.5.

Fungal organisms morphologically consistent with Candida species. Pseudohyphae and yeast forms are present. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Approximately 10% of females are carriers of Candida organisms. The incidence of Candida infection increases with pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, and diabetes. The organisms are present as yeast forms with long pseudohyphae. “Spearing” of epithelial cells by the pseudohyphae may be observed. Inflammatory cells are generally present in the background

♦

Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata lack the pseudohyphae observed in other Candida species, but may be difficult to separate on Pap test C. glabrata is primarily nonpathogenic except in immunocompromised individuals, where it may rarely be a highly opportunistic pathogen of the urogenital tract and bloodstream

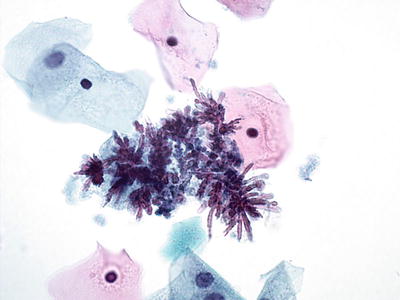

Shift in Flora Suggestive of Bacterial Vaginosis (Fig. 1.6)

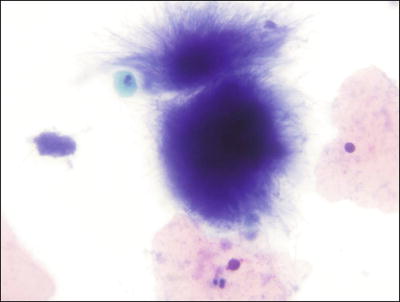

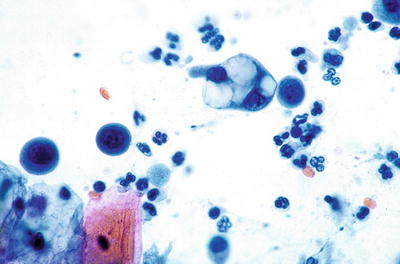

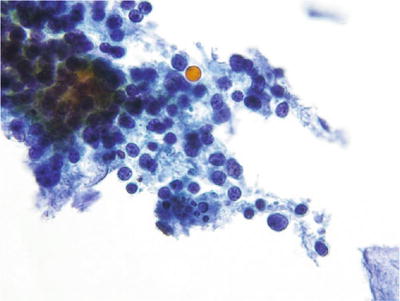

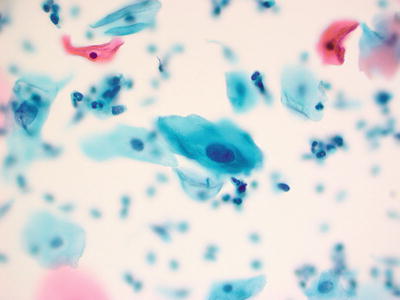

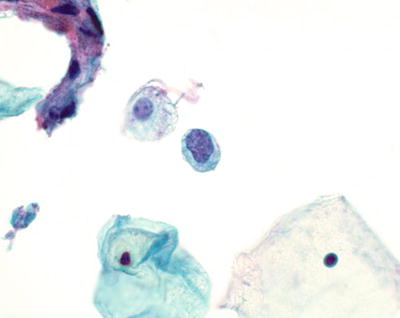

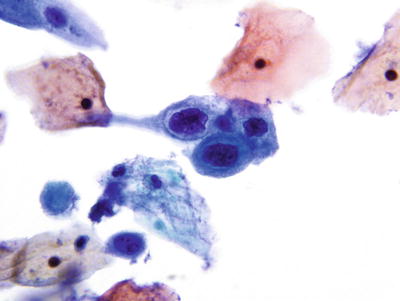

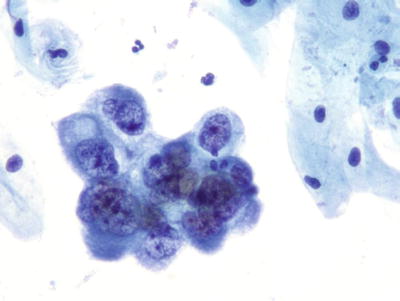

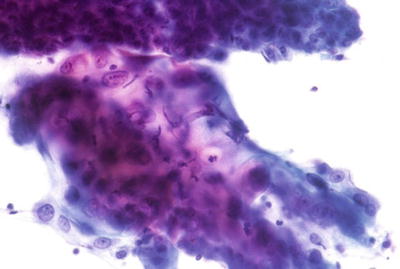

Fig. 1.6.

Shift in flora suggestive of bacterial vaginosis. Clue cells with coccobacilli covering the cytoplasm are present. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Bacterial vaginosis occurs in 10–30% of the general population. Patients have exponentially more anaerobes per ml of vaginal fluid than normal. The etiologic agents for bacterial vaginosis include Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobic lactobacilli, Bacteroides species, and Mobiluncus species. G. vaginalis (haemophilus-corynebacterium-vaginalis) may be cultured in 30–50% of asymptomatic women

♦

A combination of Pap test, wet prep, vaginal pH, and “Whiff” test on KOH preparation (positive in symptomatic women) can establish the diagnosis. The organisms are gram-variable bacilli, including numerous coccobacilli, curved bacilli, or mixed organisms imparting a “filmy” appearance to the preparation. Lactobacilli are absent. “Clue cells” refer to the presence of squamous cells covered by adherent, small, and uniformly spaced coccobacilli. This finding in Pap test alone is neither specific nor sufficient for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis

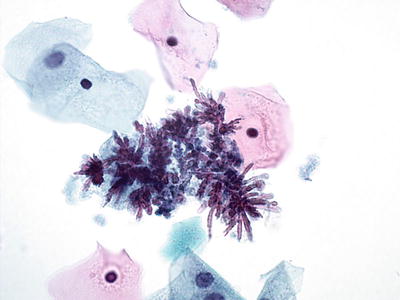

Bacteria Morphologically Consistent with Actinomyces (Fig. 1.7)

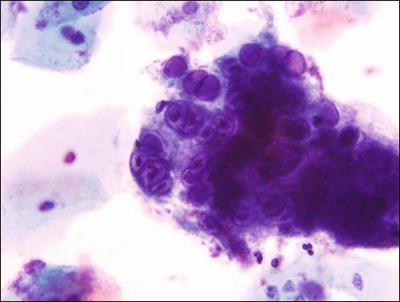

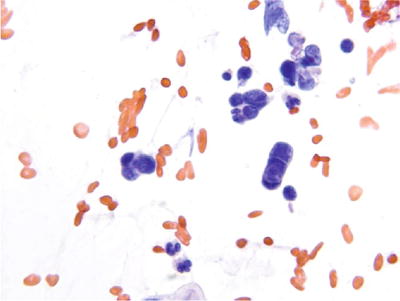

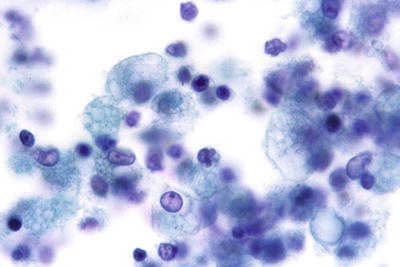

Fig. 1.7.

Bacteria morphologically consistent with Actinomyces species. A cluster of thin filamentous bacilli are present. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Actinomyces organisms are gram-positive filamentous bacteria. They are associated with the use of intrauterine devices (IUD) and vaginal pessaries. Actinomyces organisms are recognized by the presence of isolated tangled aggregates of long basophilic filamentous structures with a radiating pattern. In addition to this morphology, the organisms may be arranged in a horizontal array of filamentous structures along a central dense core, presumably representing the IUD string

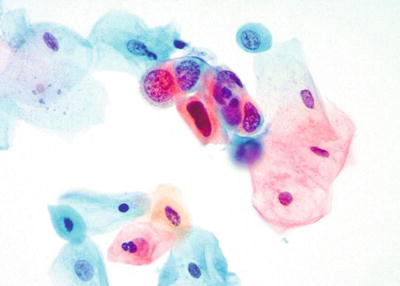

Cellular Changes Consistent with Herpes Simplex Virus (Fig. 1.8)

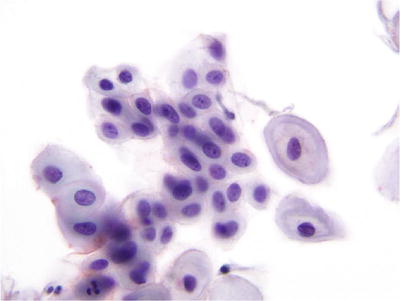

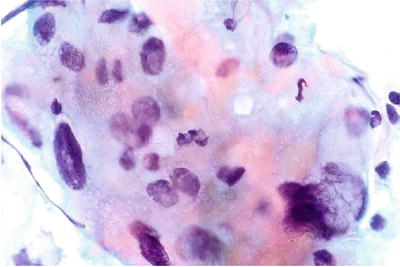

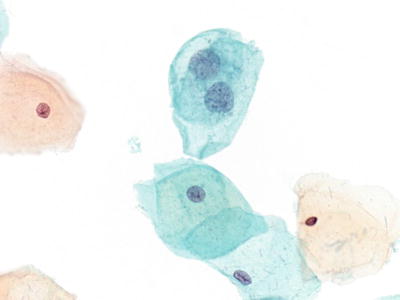

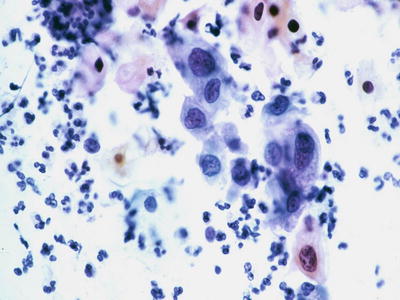

Fig. 1.8.

Cellular changes consistent with herpes simplex virus . Multinucleated giant cell with molding, ground-glass nuclei, and intranuclear inclusions LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Eighty percent of exposed females develop herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection following exposure and the recurrence rate is 60%. Herpetic infection is characterized by the presence of multinucleation, molding of nuclei, ground-glass nuclei, margination of chromatin, and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. Type I (oral) and type II (genital) herpes, as well as primary and secondary infections, cannot be distinguished cytologically

Chlamydia trachomatis

♦

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles containing eosinophilic dots (elementary particles) are not specific for C. trachomatis as they often represent mucin or other vacuoles. C. trachomatis may be associated with follicular cervicitis especially in younger patients. The Pap test has no role in the diagnosis

Lactobacillus acidophilus (Döderlein Bacilli)

♦

Lactobacillus represent a heterogeneous group of bacilli whose function is to maintain an acidic vaginal pH (3.5–4.5). They are the only species of bacteria that are capable of causing cytolysis (dissolution of cytoplasm of squamous cells) by hydrolyzing intracytoplasmic glycogen

Leptothrix

♦

Leptothrix are filamentous negative rods with or without branching. They are often associated with the presence of another organism (Trichomonas, Candida, etc.)

Molluscum Contagiosum (Pox Virus)

♦

Molluscum contagiosum is characterized by the presence of large cells with eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions (Henderson-Patterson bodies) and pyknotic degenerative nuclei

Enterobius vermicularis (Pinworm)

♦

Enterobius vermicularis has ovoid-shaped eggs with a double-walled shell which is flattened on one side

Entamoeba histolytica

♦

Entamoeba histolytica organisms are large trophozoites with large nuclei and a dot-like central karyosome. Their cytoplasm is vacuolated and contains ingested RBCs

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

♦

Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent women is usually transient and asymptomatic. The infected cells are enlarged with a solitary basophilic intranuclear inclusion surrounded by a halo. Intracytoplasmic small granular inclusions may also be observed

Contaminants

♦

Alternaria . Air-borne contaminant fungi that have short yellow-brown conidiospores with transversely and longitudinally septate macroconidia (snow shoe-like) (Fig. 1.9)

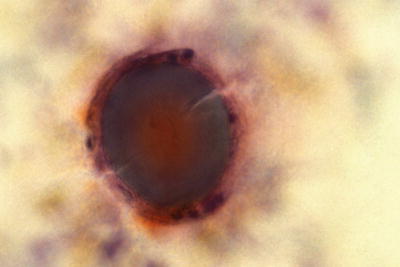

Fig. 1.9.

Alternaria. Brown macroconidia with transverse and longitudinal septa. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Pollen. Air-borne contaminate that is oval to round with smooth, refractile borders and no internal structure (Fig. 1.10)

Fig. 1.10.

Pollen. Round granule with smooth refractile borders. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Vegetable cells. Vegetable cells have dense cell walls and structureless nuclei. They may be observed in patients with rectovaginal fistulas along with goblet cells, inflammation, and necrotic debris

♦

Graphite–pencil markings

♦

Lubricant jelly. Not recommended for gynecologic examination prior to Pap test

♦

Cotton, cardboard, and tampon fibers

♦

Trichome. “Octopus-like” or star-shaped structure derived from leaves of arrow-wood plant

♦

Carpet beetle parts. Arrow-shaped structures that may have origin from tampon or gauze pads

♦

Cockleburs. Associated with IUDs, oral contraceptive use, and second half of pregnancy. They are related to cellular degeneration and composed of nonimmune glycoprotein, lipid, and calcium. Cytologically, they are identified as refractile crystalline rays surrounded by histiocytes. They have no clinical significance (Fig. 1.11)

Fig. 1.11.

Cockleburs. Refractile crystalline rays surrounded by histiocytes. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Hematoidin crystals. Composed of bile-like pigment formed from hypoxic tissue, indicative of previous hemorrhage, but does not contain iron. Cytologically, they have finer crystalline rays than cockleburs with variable shapes

♦

Talc particles

♦

Ferning. Represents arborizing palm leaves-like pattern of cervical mucus that occurs at ovulation

♦

“Cornflaking.” A refractile brown processing artifact representing air-trapping between the squamous cells and the cover slip. It can be resolved by recoverslipping (Fig. 1.12)

Fig. 1.12.

“Cornflaking.” Brown refractile artifact overlying squamous cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Sperm. May be identified in the Pap test for a few days after intercourse. This information is not to be included in the report. Any inquiry should have prompt referral of the slide through the appropriate legal channels

Reactive Changes

Typical Repair (Figs. 1.13 and 1.14)

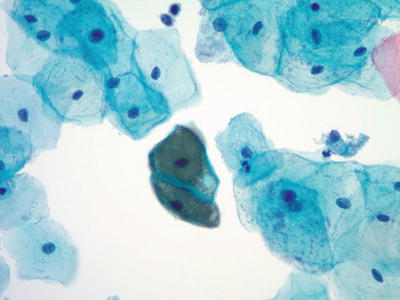

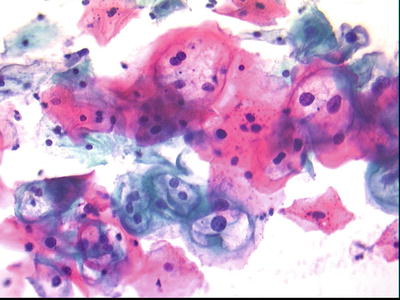

Fig. 1.13.

Reactive cellular changes associated with inflammation. Sheet of squamous cells with distinct borders, abundant cytoplasm, enlarged uniformly round nuclei, and nucleoli. Isolated atypical cells are not observed. CP conventional preparation.

Fig. 1.14.

Reactive cellular changes . Flat sheet of squamous cells with slightly enlarged uniform nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, and nucleoli. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes are present in the background. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Cytologic Features

♦

Characterized by the presence of flat, cohesive sheets of squamous or glandular cells with cellular streaming and pseudopodia (peripheral cytoplasmic projections). No single cells and no tumor diathesis are present

♦

The nuclei are enlarged with fine chromatin and smooth nuclear contours. There are prominent nucleoli that are often multiple and regular

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) presents as single abnormal cells. Tumor cells have an irregular chromatin distribution and multiple irregular nucleoli. A tumor diathesis is present

♦

Acantholytic cells in pemphigus vulgaris may be observed in vaginal smears. Isolated single cells are referred to as tombstone cells. Correlation with clinical history is essential for accurate interpretation of cells derived from pemphigus vulgaris

Radiation Effect (Figs. 1.15 and 1.16)

Fig. 1.15.

Reactive cellular changes associated with radiation effect. Large intermediate and metaplastic cells with enlarged nuclei and abundant cytoplasm. Note the cytoplasmic polychromatic staining and vacuolization. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.16.

Reactive cellular changes associated with radiation effect. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Cytologic Features

♦

Cellular enlargement (macrocytosis) and nuclear enlargement, but the nuclear/cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio remains normal. There are nuclear and cytoplasmic vacuoles present with reactive perinuclear halos. Cellular chromatin is finely granular or degenerative (“smudged”). Karyorrhexis and karyopyknosis are observed

♦

Binucleation and multinucleation and micro-and macronucleoli are typical of radiated cells. Large bizarre cells with polychromasia, peripheral cytoplasmic projections (pseudopodia), and cytophagocytosis including intracytoplasmic neutrophils are observed

Intrauterine Device (IUD)-Associated Changes (Fig. 1.17)

Fig. 1.17.

Reactive cellular changes associated with intrauterine contraceptive device. Glandular cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles displacing the nuclei. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Cytologic Features

♦

Small clusters of hypersecretory endocervical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large cytoplasmic vacuoles (bubblegum cytoplasm), and distinct cell borders

♦

Nuclei are large and uniform and may contain prominent nucleoli. Inflammatory/reparative squamous changes may be present

♦

The background is generally clean or inflammatory. Actinomycotic colonies and calcified debris may be observed

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Adenocarcinoma of endometrium occurs in older patients (postmenopausal) and is characterized by the presence of many abnormal cells with an irregular chromatin pattern and associated tumor diathesis

Atrophy (Figs. 1.18 and 1.19)

Fig. 1.18.

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy. Atrophy. Maturation is not observed. Smear consists predominantly of parabasal cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.19.

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy. Atrophy. Granular background, basal cells, and “blue blobs”. CP conventional preparation.

♦

Generally observed in older women or postpartum

Cytologic Features

♦

Predominance of basal and parabasal cells, either as single cells or in tissue-like sheets. The borders of cell groups are smooth and defined

♦

Atrophic cells show generalized and mild nuclear enlargement with smooth nuclear contours. The chromatin usually appears fine and uniform. No mitotic figures or apoptosis are noted

♦

Air-drying and degeneration may result in autolysis (bare nuclei), orangophilic change in the cytoplasm (pseudoparakeratosis), and a granular background. These changes are more common in CP than in LBC. These background changes can be similar to the tumor diathesis seen in SCC and distinguished only by the absence of malignant cells in atrophy

♦

“Blue blobs” which represent inspissated mucus or nuclear material are often seen in atrophic smears and may mimic atypical cells

Hyperkeratosis (HK )

♦

Often represents a nonspecific reaction to chronic cervicitis, uterine prolapse, previous biopsy, cryosurgery, or instrumentation or as a manifestation of in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure

♦

Approximately 10% may represent a surface reaction overlying squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL) or a response to persistent or recurrent disease in patients with prior biopsy or cytology-proven SIL

♦

The presence during pregnancy suggests ruptured fetal membranes

♦

Rare, isolated anucleated cells often represents contaminants from vulva or vagina

Cytologic Features

♦

Clusters or groups of anucleate and granular superficial polygonal squamous cells

Parakeratosis (PK) (Fig. 1.20)

Fig. 1.20.

Reactive cellular changes. Parakeratosis. Superficial squamous cells with uniform, pyknotic nuclei. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Similar to hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis represents a reactive surface process due to chronic irritation, but may be seen with cervical dysplasia

♦

Persistence of parakeratosis without a known etiology may warrant further investigation to exclude an associated SIL

Cytologic Features

♦

Isolated or loose sheets of superficial squamous cells with dense orangophilic cytoplasm and small uniform pyknotic nuclei

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Degeneration can cause a “pseudoparakeratosis” with pyknotic nuclei and cytoplasmic eosinophilia in cases of atrophy or severe inflammation. It is associated with other signs of degeneration, such as karyorrhexis, vacuolization, and cytolysis

Chronic Follicular (Lymphocytic) Cervicitis (Fig. 1.21)

Fig. 1.21.

Reactive cellular changes. Chronic lymphocytic cervicitis. Polymorphous population of lymphoid cells with tingible body macrophages. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Approximately 50% of cases are associated with Chlamydia, but it can also be commonly seen in postmenopausal atrophic specimens

Cytologic Features

♦

Polymorphous population of mature lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes with characteristic “tingible” body macrophages. Reactive glandular and squamous changes may be observed

Folic Acid Deficiency

Cytologic Features

♦

Similar cytologic changes to those of early radiation effect, including nuclear and cellular enlargement, nuclear enfolding, and multinucleation. The nuclei are hyperchromatic with smooth contours. Cytoplasmic vacuolization and polychromasia are usually observed

Navicular Cells

♦

Observed in pregnancy, late in the menstrual cycle, and in the setting of high progesterone medications

Cytologic Features

♦

Boat-like intermediate cells with ecto-endoplasmic differentiation and glycogen, which may have a yellow hue with Pap stain

Decidual Cells (Figs. 1.22, 1.23, and 1.24)

Fig. 1.22.

Decidua. These cells were observed on a Pap smear from a pregnant woman. They show abundant eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm and enlarged nuclei with smudged chromatin pattern. CP conventional preparation.

Fig. 1.23.

Decidua. These cells show a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and cytomorphologically mimic ASC-H. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.24.

Decidua. From same patient as Fig 1.23 demonstrating round cells with abundant cytoplasm. There are occasional cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (histology, H&E).

♦

May be seen in Pap tests from pregnant women and women on birth control pills or progesterone therapeutic agents. Clinical history is important for accurate interpretation

Cytologic Features

♦

Isolated cells or loose sheets of large, polygonal, or round cells with abundant granular, eosinophilic, or amphophilic cytoplasm. Slight to moderate nuclear enlargement is present, but the N:C ratio usually remains low. The nuclei are round with vesicular or smudged chromatin and degenerative changes. Nucleoli may be prominent

♦

Rarely, decidual cells can mimic squamous and glandular abnormalities and have high N:C ratio (Fig. 1.23)

Trophoblasts

♦

Rarely seen in normal pregnancy

Presence may indicate threatened abortion when observed in the first trimester of pregnancy (6% of patients)

Partial premature separation of the placenta should be suspected when trophoblasts are observed in the third trimester

Retained placental tissue should be suspected when trophoblasts are observed 4 weeks after termination of pregnancy

Cytologic Features

♦

Syncytiotrophoblasts have abundant cyanophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders. Their multiple nuclei (20+) are round to oval with nuclear overlapping but without molding. The chromatin is finely granular and evenly distributed with inconspicuous nucleoli

♦

Cytotrophoblasts are large cells with uniformly amphophilic cytoplasm and large irregular nuclei that may be lobulated and vacuolated

Squamous Cell Abnormalities

Atypical Squamous Cells (ASC)

Definition

♦

Cytologic changes suggestive of SIL that are quantitatively or qualitatively insufficient for a definitive interpretation. Atypical squamous cell (ASC) does not represent a single biologic entity. ASC is subdivided into two categories: ASC of undetermined significance and ASC cannot exclude HSIL

♦

The category of ASC is by far the most commonly reported abnormal cervical cytology interpretation. The ASC category was developed to designate the interpretation of an entire specimen, not individual cells, because atypia in individual cells remains highly subjective with variable interpretation

Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASC-US) (Figs. 1.25, 1.26, and 1.27)

Fig. 1.25.

ASC-US . Atypical intermediate squamous cells with round hyperchromatic nuclei that are at 2.5–3 times the size of the adjacent normal intermediate cell nuclei. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.26.

ASC-US. Intermediate cells with nuclear enlargement. No inflammation is present in the background. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.27.

ASC-US . Atypical parakeratosis. Spindled and slightly pleomorphic orangophilic parakeratotic cells with mild nuclear enlargement. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Represents greater than 90% of all ASC. The average reporting rate is 4.5–5.0% of Pap tests

♦

The ASC-US-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) trial showed that approximately 50% of patients with ASC-US have oncogenic high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) types

Cytologic Features

♦

ASC-US may manifest a wide range of cytologic features. Designation by cell type of origin is not used; however, these are listed below to assure recognition of ASC-US and to separate it from other, often overlapping, manifestations of reactive cells or more advanced cytologic epithelial abnormalities:

ASC-US involving intermediate or superficial squamous cells represents the most common pattern (Figs. 1.25 and 1.26). The cells are usually isolated and few in number. Nuclear size is 2½–3× size of an intermediate cell nucleus (70–120 μm2). There is a slight increase in N:C ratio. Minimal nuclear hyperchromasia, irregularity, clumping, smudging, or multinucleation may be observed. ASC-US cells do not include inflammatory or reparative/reactive “atypia”

ASC-US cells originating from squamous metaplastic cells have an enlarged nuclei 2× size of the nucleus of a normal immature squamous metaplastic cell. The cytoplasm distinguishes the nuclei as metaplastic; it is less abundant and more cyanophilic and dense. Additionally, the cells are more round with an N:C ratio higher than intermediate or superficial squamous cells

ASC-US may be used when atypical repair is present. Atypical repair has all the features of typical repair in addition to concerning cytologic features, such as cellular overlap, slight lack of cohesion, loss of nuclear polarity, anisonucleosis, and irregularity of nuclear contour. Prominent single or multiple nucleoli are present, as well as mitotic figures and an inflammatory background. If the “atypia” described above is prominent and concerning for HSIL or a more advanced lesion, then atypical repair can be considered under the ASC-H category

ASC-US may be seen in a background of atrophy. Normal atrophic specimens show nuclear enlargement with concomitant hyperchromasia, but if there is marked irregularities in cell shape, nuclear contours, or chromatin distribution, ASC-US may be reported

ASC-US can be used in the setting of atypical parakeratosis (Fig. 1.27). These cells demonstrate the cytologic features seen in parakeratosis except the nuclei are enlarged and more pleomorphic with irregular nuclear borders

Cells with equivocal changes for HPV are placed in the ASC-US category. These cells manifest partial koilocytes or perinuclear halos without nuclear abnormalities. Bi- or multinucleation may be observed

Differential Diagnosis

♦

CP smears may manifest drying artifact that may cause the nuclei to appear larger and washed-out, thus simulating ASC-US. This phenomenon has been almost eliminated by LBC

♦

LSIL shows more marked nuclear enlargement (greater than 3× the size of an intermediate squamous cell nucleus), hyperchromasia, and irregularities of nuclear contour. HPV cytopathic effect is synonymous with SIL

Atypical Squamous Cells, Cannot Exclude HSIL (ASC-H) (Figs. 1.28 and 1.29)

Fig. 1.28.

ASC-H. Atypical immature metaplastic cells with enlarged nuclei and nuclear irregularity. Only rare atypical cells were present. The findings are not diagnostic of HSIL. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.29.

ASC-H . Atypical immature metaplastic cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Defined as having cytologic changes that are suggestive of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), but lack ample cytomorphologic features for definitive interpretation

♦

Constitutes approximately 5% of all ASC. The median reporting rate is 0.2–0.3% of Pap tests

♦

The association of ASC-H with underlying CIN2 and CIN3 (30–40%) is lower than for HSIL, but sufficiently higher than for ASC-US. This warrants different clinical management recommendations for ASC-H compared to ASC-US. A few cases of ASC-H may have invasive carcinoma on biopsy (2–3%)

♦

The ALTS trial noted that approximately 70–80% of ASC-H cases have oncogenic HR-HPV types

Cytologic Features

♦

ASC-H may be observed as “atypical immature metaplastic cells.” These occur as small single cells or in tight clusters of usually less than 10 cells. These cells resemble normal metaplastic cells with amphophilic cytoplasm and high N:C ratio but have a slightly larger nuclear size (1.5–2.5× that of normal metaplastic cell nuclei) with nuclear irregularities and mildly hyperchromasia

♦

ASC-H can be used for loose clusters of cells demonstrating markedly atypical repair if the N:C ratio is high and there is nuclear pleomorphism present, raising the possibility of SIL or carcinoma in the differential diagnosis

♦

An interpretation of ASC-H may be rendered for thick tissue fragments or hyperchromatic crowded groups (see section below). The cells show loss of polarity or are difficult to completely visualize, but raise the possibility of HSIL

♦

ASC-H can also be used for rare isolated atypical small cells that do not show features of immature metaplastic cells. These cells demonstrate high N:C ratio, nuclear irregularities or grooves, and hyperchromasia, but without typical cytoplasmic changes seen in metaplastic cells

Differential Diagnosis

♦

ASC-US cells are usually mature squamous cells with low N:C ratio

♦

Immature metaplastic cells have regular round nuclei and uniform finely granular chromatin

♦

HSIL cells are usually more numerous, often occurring in syncytial aggregates, and demonstrate more pronounced nuclear hyperchromasia, nuclear irregularities, and coarse granular chromatin

♦

Endometrial cells are smaller, exfoliate in three-dimensional clusters, and have an eccentric nucleus with finely granular chromatin

♦

Histiocytes have foamy cytoplasm, bean-shaped nuclei, and low N:C ratio

Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (SIL )

♦

Encompasses a spectrum of noninvasive cervical epithelial abnormalities traditionally classified as flat condyloma, dysplasia/carcinoma in situ, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN):

Low-grade SIL (LSIL) includes the cellular changes associated with HPV cytopathic effect and mild dysplasia (CIN1)

High-grade SIL (HSIL) encompasses moderate dysplasia, severe dysplasia (CIN2, 3), and carcinoma in situ (CIS)

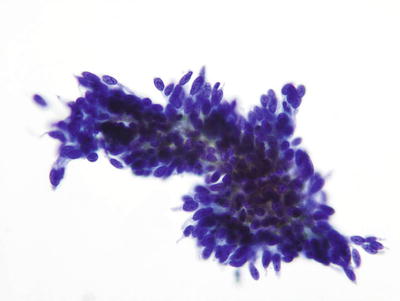

Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) (Figs. 1.30, 1.31, and 1.32)

Fig. 1.30.

LSIL Intermediate squamous cells with mild nuclear enlargement and nuclear contour irregularities. Perinuclear halos consistent with HPV effect are present. HPV human papillomavirus, LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.31.

LSIL . Intermediate squamous cells with enlarged nuclei and hyperchromasia. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.32.

LSIL (CIN1). Disordered proliferation of dysplastic cells in the lower third of the epithelium and HPV effect toward the surface (histology, H&E).

Cytologic Features

♦

LSIL is characterized by nuclear enlargement greater than 3× size of an intermediate squamous cell nucleus (often 5–6× the size, greater than 150 μm2), hyperchromasia, and nuclear irregularities. The chromatin pattern is usually finely granular and uniformly distributed. Nucleoli are generally inconspicuous or absent

♦

HPV cytopathic effect is characterized by large perinuclear halos with sharp borders and dense surrounding peripheral cytoplasm (koilocytes). The nuclei of koilocytes are enlarged and hyperchromatic with slightly irregular nuclear contours

♦

Dyskeratosis, binucleation, multinucleation, and nuclear pleomorphism may be observed in these cells. Tumor diathesis is absent

♦

LSIL in LBC may demonstrate decreased hyperchromasia, increased nuclear detail, and more apparent nuclear membrane irregularities compared to CP smears

Differential Diagnosis

♦

HSIL exhibits significant increase in the N:C ratio, hyperchromasia, and marked chromatin irregularities. The cells are usually arranged in syncytial aggregates

♦

ASC-US cells tend to be few in number and have slight nuclear enlargement (2.5–3× intermediate cell nucleus). The chromatin pattern in ASC-US is finer and the nuclear membranes are less irregular

♦

LSIL cannot exclude HSIL (LSIL-H): Occasionally, a specimen is encountered with cytologic features that lie between LSIL and HSIL, especially if there are few cells that meet criteria of ASC-H that are identified in a background of LSIL. The 2014 Bethesda system nomenclature maintains that classification into either LSIL or HSIL is possible in most instances. The Bethesda system does not advocate the use of LSIL-H category, which does not have an associated ASCCP management guideline. There will remain, however, an occasional case in which it is not possible to categorize an SIL and a comment explaining the nature of the uncertainty may be employed. An interpretation of ASC-H may be made in addition to a LSIL interpretation, which should lead to colposcopic evaluation, especially in young women. This dual interpretation should comprise only a minority of cases

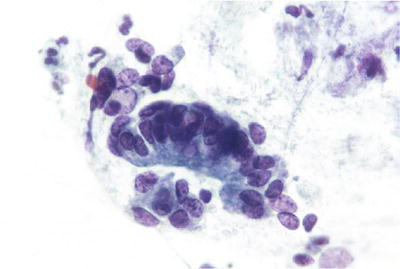

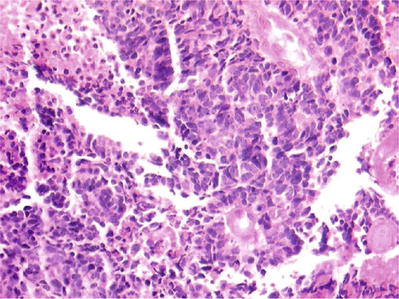

High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HSIL) (Figs. 1.33, 1.34, 1.35, 1.36, and 1.37)

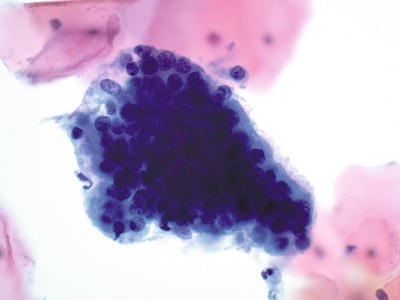

Fig. 1.33.

HSIL . Metaplastic cells with enlarged nuclei, irregular nuclear contours, and coarse chromatin pattern. Subsequent biopsy revealed HSIL (CIN2). LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.34.

HSIL . Loose arrangement of small immature cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, markedly irregular nuclear contours, and coarsely granular chromatic pattern (subsequent biopsy revealed HSIL/CIN2). CP conventional preparation.

Fig. 1.35.

HSIL . Syncytial cluster of small cells with very high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, markedly irregular nuclear contours, and coarse but equally distributed chromatic pattern. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.36.

HSIL . Syncytial cluster of cells with enlarged nuclei, irregularities of nuclear contour, and coarse chromatin pattern. (Subsequent biopsy revealed HSIL/CIN3). LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.37.

CIN3. Severe dysplasia (carcinoma in situ). Full-thickness disordered maturation with dysplastic cells showing hyperchromatic nuclei and high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (histology, H&E).

♦

The focus of cervical cancer screening is primarily aimed at detection and treatment of HSIL

Cytologic Features

♦

HSIL shows increased N:C ratio (the overall cell size and nuclear size, however, are smaller than LSIL) and abnormal nuclear features. In LBC, the nuclear membrane irregularities are distinctly prominent, and hyperchromasia is often observed as coarsening of chromatin material rather than darkening of the nuclear stain in CP smears. Generally, HSIL cells tend to be round to oval with lacy, delicate, or metaplastic cytoplasm

♦

HSIL often occurs in cell aggregates (hyperchromatic crowded groups) and syncytial-like arrangements. In LBC, HSIL cells may be fewer in number and more isolated or present in small groups due to processing. Tumor diathesis is absent

♦

“ Keratinizing dysplasia” refers to the pleomorphic appearance of the cells rather than cytoplasmic staining. The cells exhibit pleomorphism with marked anisonucleosis (caudate, spindle, elongated, tadpole, or bizarre forms) and dense orangophilic cytoplasm with distinct borders. It can be difficult to grade keratinizing dysplasia because it may show a greater degree of pleomorphism

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other causes of hyperchromatic crowded groups can be confused with HSIL

♦

Invasive SCC is characterized by marked cellular pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, and the presence of tumor diathesis

♦

Endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) is characterized by a picket-fence arrangement of columnar cells with peripheral palisading (“feathering”) and granular cytoplasm. The nuclei are usually oval and monotonous. This contrasts with the disordered syncytial arrangement of HSIL cells, which are smaller and exhibit variation in nuclear size and shape. HSIL is much more common than AIS and in difficult cases an interpretation of HSIL is generally rendered. A note can be added that the possibility of glandular origin cannot be excluded

♦

It may be also difficult to distinguish keratinizing dysplasia from keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (KSCC) . KSCC generally has less cohesive cells and more marked nuclear pleomorphism. As such, keratinizing dysplasia is sometimes designated as SIL-ungraded to assure that a biopsy is obtained to evaluate for the presence of invasive carcinoma

Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC ) (Figs. 1.38, 1.39, 1.40, and 1.41)

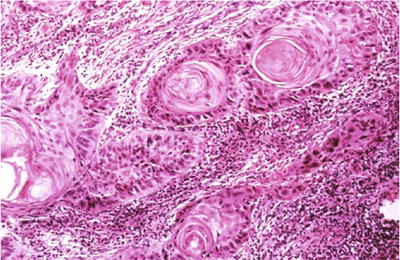

Fig. 1.38.

Squamous cell carcinoma (keratinizing type). Markedly pleomorphic orangophilic cells are present. The nuclei are irregular with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and irregular coarse chromatin pattern. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.39.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma , keratinizing type. Keratin pearls are present in this invasive moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (histology, H&E).

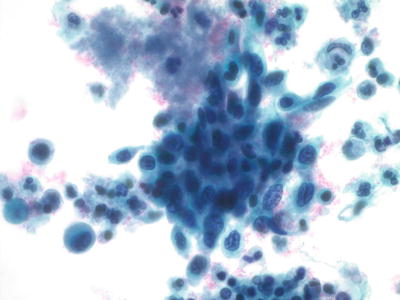

Fig. 1.40.

Squamous cell carcinoma (large cell nonkeratinizing type). Cluster of malignant cells with pleomorphic nuclei, irregular chromatin pattern, and nucleoli. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

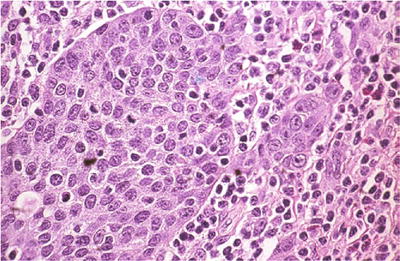

Fig. 1.41.

Squamous cell carcinoma, large cell nonkeratinizing type. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma that lacks squamous pearls (histology, H&E).

Cytologic Features

♦

SCC is characterized by single abnormal cells with loss of cellular and nuclear polarity. The carcinoma cells are about 1/5 or less the size of normal superficial or intermediate squamous cells. The nuclear size is about 2–4× that of intermediate squamous cell nucleus. The N:C ratio is very high and the chromatin is coarse and irregularly distributed with parachromatic clearing and nuclear molding

♦

Tumor diathesis, which consists of the host response of lysed blood, cellular debris, inflammatory cells, and protein precipitate, is generally observed in over 50% of cases

♦

In LBC, SCC cells may demonstrate a greater depth of focus of cell groups. The nuclei maintain features indicative of malignancy but are usually less hyperchromatic when compared to CP smears. In addition, in LBC, nucleoli are more prominent and there is a distinctive necrotic background pattern consisting of debris immediately surrounding individual cells or clusters of cells (clinging diathesis)

Variants

♦

Keratinizing SCC (KSCC) shows significant pleomorphism with spindle, bizarre, tadpole, and caudate cells. They have a dense keratinizing orangophilic cytoplasm with distinct cell borders. Their nuclei are pleomorphic and hyperchromatic with coarsely clumped chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. Anucleated squamous cells and atypical parakeratotic cells may be present in the background. KSCC may lack tumor diathesis (Figs. 1.38 and 1.39)

♦

Large cell nonkeratinizing (LCNK) SCC shows less anisocytosis and anisonucleosis. There are numerous abnormal single cells and syncytial groups of cells with high N:C ratio, dense cytoplasm, and indistinct borders. The nuclei tend to be round to oval with nuclear overlapping, coarse granular chromatin with chromatin clearing, and macronucleoli. Tumor diathesis is present (Figs. 1.40 and 1.41)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

HSIL cells do not exhibit significant nuclear molding, chromatin clearing, or tumor diathesis

Hyperchromatic Crowded Groups (HCG )

♦

Generally refers to readily identified three-dimensional aggregates of crowded cells with dark nuclei. Some may be reminiscent of microbiopsies

♦

The majority of cases are due to a benign or reactive process:

Examples: follicular cervicitis, exodus, atrophy, aggressively sampled endocervical cells, lower uterine segment endometrium, and benign mimickers of endocervical glandular atypia

♦

Less frequently (less than 5%) HCGs may represent sampling of a significant lesion, either squamous (discussed above) or glandular (discussed below):

Examples: HSIL, AIS, and adenocarcinomas of the endocervix or endometrium

♦

In general, HCGs can usually be recognized as to their respective nature, however, some remain difficult to interpret. All require careful review for features that favor a neoplastic process such as disorganized architecture, pleomorphic cells with anisonucleosis, atypical isolated cells, prominent nucleoli, and mitosis

Normal and Reactive Endocervical Cytology

Cytologic Features

♦

Normal endocervical cells may occur singly or in strips, rosettes, or sheets. They are usually elongated and columnar. When viewed on end, they are polygonal or cuboidal and demonstrate the typical “honeycomb” arrangement. The nuclei are round to oval and are often indented or possess a protrusion of the nuclear contents at one end. The nuclear chromatin is finely granular and evenly dispersed. Multiple small chromocenters and one or more small eosinophilic nucleoli may be present. Binucleation or multinucleation is not uncommon. The cytoplasm of endocervical cells is usually described as granular, but it may show fine vacuolization. Variability is observed in cells derived from various regions of the endocervical canal

♦

Endocervical cells with reactive/reparative changes occur in sheets and strips with minor degrees of nuclear overlap. They may exhibit nuclear enlargement, up to 3–5× the size of normal endocervical nuclei. Mild variation in nuclear size and shape occurs. Slight hyperchromasia is frequently evident. Nucleoli are often present. The cells usually have abundant cytoplasm. Distinct cell borders are discernible. Rarely mitotic figures may be seen in repair

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Neoplastic endocervical cells demonstrate crowding, secondary gland formation, and elongated or irregular nuclei. In addition, mitotic figures and apoptosis are often observed

Tubal Metaplasia (Figs. 1.42 and 1.43)

Fig. 1.42.

Negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy. Endocervical cells, tubal metaplasia. A strip of ciliated columnar endocervical cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.43.

Tubal metaplasia . Ciliated tubal epithelium lines an endocervical gland (histology, H&E).

♦

A normal finding especially in the upper endocervical canal

Cytologic Features

♦

The presence of terminal bars and cilia is the characteristic feature. Cells tend to form small crowded cellular strips, clusters, or flat honeycomb sheets. They have evenly spaced, uniform, and basally oriented round to oval nuclei. The nuclei are finely granular with evenly distributed dark or washed-out chromatin. Small inconspicuous nucleoli may be observed. Mucus depletion and ciliocytophthoria may be present

Differential Diagnosis

♦

AIS cells lack terminal bars or cilia, show nuclear hyperchromasia and a coarse chromatin pattern, and demonstrate nuclear feathering and rosettes. Apoptosis is only observed in AIS

Microglandular Endocervical Hyperplasia

♦

Related to progesterone effect and may be related to pregnancy, birth control pills, and estrogen use in postmenopausal women

Cytologic Features

♦

Not distinctly recognized on cytology. Usually indistinguishable from endocervical reactive hyperplasia and regeneration/repair

♦

Large sheets of polygonal or columnar cells with minimal stratification, pseudoparakeratotic degenerative changes, and abundant fine or vacuolated cytoplasm. The nuclei are normal or mildly increased in size with normal or slightly hyperchromatic chromatin. Nucleoli may be present and prominent. Terminal bars and cilia may be present

Arias-Stella Reaction

♦

Nonneoplastic hormone-related phenomenon that is usually observed in pregnancy. Clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis

Cytologic Features

♦

The cytologic features are not specific and the interpretation is often that of atypical endocervical cells (AEC)

♦

Single or small groups of “atypical” glandular cells with low N:C ratio and abundant clear or faintly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, and nuclear grooves can be observed. Nuclei are often smudged with ground-glass appearance

Benign Glandular Cells in the Specimens from Post-Hysterectomy Women

♦

Prior to documenting the presence of benign glandular cells in the setting of a post-hysterectomy “vaginal Pap test,” it is important to assure that the “hysterectomy” was not supracervical. Also observe that the cells in question are truly glandular and not a mimic, such as atrophy

♦

The likely sources of benign glandular cells include prolapse of uterine tube, vaginal endometriosis, fistula, vaginal adenosis not associated with DES exposure, or glandular metaplasia associated with prior radiation or chemotherapy. Sometimes the reason remains unknown

♦

These findings are considered benign and do not warrant an interpretation/diagnosis of “atypical glandular cells” (AGC)

Glandular Cell Abnormalities

♦

The Pap test was not designed to screen for cervical glandular lesions and these abnormalities are more difficult to detect and interpret than squamous lesions. The improvement in sampling devices and the documented increase in endocervical adenocarcinoma have resulted in recognition of a spectrum of glandular changes, lesions, and mimics

♦

Whenever possible, atypical glandular cells (AGC) should be qualified as favor endocervical or favor endometrial in origin. When the distinction cannot be made, the cytology report of AGC should indicate the uncertainty as to the source of these cells

♦

The diagnosis of AGC in the typical cytology laboratory is infrequent (0.3–1%)

♦

For AGC and AEC, colposcopy with endocervical sampling is indicated. Cases diagnosed as AGC have approximately a 13% risk of CIN2 or worse and 2.8% risk of cancer. Endometrial sampling is added if the patient’s age is over 35 or they are having abnormal bleeding, regardless of HPV result. AEM is managed by endometrial and endocervical sampling

Atypical Endocervical Cells (AEC ) (Fig. 1.44)

Fig. 1.44.

Atypical endocervical cells . A strip of pseudostratified atypical endocervical cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Cytomorphologic changes beyond those encountered in reactive processes, but qualitatively or quantitatively fall short of an unqualified diagnosis of AIS or endocervical adenocarcinoma

♦

Follow-up reveals that 20–40% of cases diagnosed as AEC are normal, reactive, or benign processes; 35–80% are derived from SIL; and 0–11% represent endocervical abnormalities. This demonstrates the inherent difficulties in the interpretation of these lesions. SIL may involve endocervical glands and mimic glandular cells

Cytologic Features

♦

Columnar cells with mild cellular crowding without nuclear pseudostratification, nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, and anisocytosis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

HSIL often demonstrates syncytial groups, opaque hyperchromatic nuclei, dense cytoplasm, and the presence of individual SIL cells

Atypical Endocervical Cells, Favor Neoplastic (Fig. 1.45)

Fig. 1.45.

Atypical endocervical cells, favor neoplastic. A strip of pseudostratified atypical endocervical cells and a disorganized cluster of similar cells. The findings fall short of those characteristic of AIS. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Cells have some but not all the criteria as outlined for AIS below or other “atypical” presentation which should be individually and specifically categorized in a qualifying statement

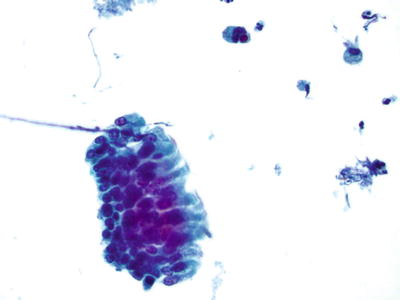

Endocervical Adenocarcinoma In Situ (AIS ) (Figs. 1.46, 1.47, and 1.48)

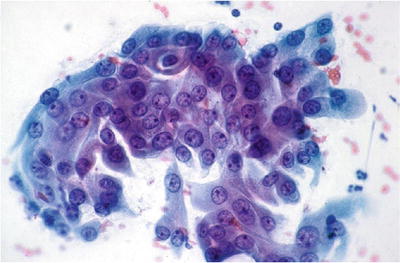

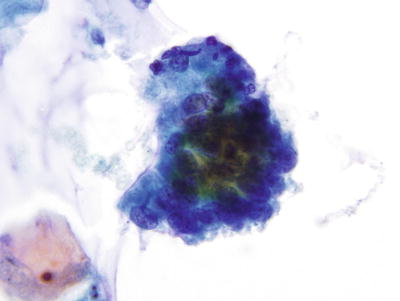

Fig. 1.46.

AIS. Hyperchromatic endocervical cells with pseudostratification and feathering. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.47.

AIS. High power image of three-dimensional clusters of endocervical cells with enlarged elongated nuclei and coarsely granular chromatin. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.48.

AIS. Endocervical gland with pseudostratification of enlarged hyperchromatic elongated nuclei adjacent to normal endocervical glandular epithelium (histology, H&E).

♦

Preservation of normal glandular architecture with involvement of part or all of the epithelium lining glands or the surface

♦

Associated with HPV 16 and 18 in 90% of cases

♦

Approximately 30–50% of AIS cases are associated with SIL

Cytologic Features

♦

“Endocervical type” of AIS is characterized by moderate to high cellularity of tight clusters and cohesive sheets of glandular cells showing pseudostratification, rosette formation, palisades, secondary gland openings, and feathering at the edge of sheets. The abnormal endocervical cells have uniform nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, nuclear irregularities, and crowding with elongated nuclei

♦

In LBC, AIS may manifest as hyperchromatic crowded groups (see above). These cells have dense immature cytoplasm, increased N:C ratio, large nuclei (70 μm2), nuclear overlap, even chromatin with coarse granularity, micronucleoli, mitosis, and apoptotic bodies. There is often difficulty with visualization of individual nuclei in the groups; a “disordered honeycomb” arrangement suggests an endocervical origin. Some architectural features may be more subtle in LBC, for example, the margins of the groups become smoother and sharper with lesser degrees of nuclear protrusion (feathering), but pseudostratified should still be evident

♦

The cytoplasm is delicate and finely vacuolated or granular with diminished mucin production

♦

The background is usually clean or inflammatory

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Tubal metaplasia is characterized by the presence of scant cellularity and cells with terminal bars and cilia. The nuclei are round to oval and more evenly spaced than those observed in AIS and the chromatin is finely granular. Mitoses, apoptosis, and nuclear hyperchromasia are not observed

♦

Repair/reactive cells are characterized by the presence of flat sheets of polygonal cells in a distinct honeycomb arrangement. Single atypical cells are absent. The cells have abundant cytoplasm and well-delineated cell borders. They are uniform cells with low N:C ratio. Minor degrees of nuclear overlap, nuclear enlargement, and variation in nuclear size and shape may be seen. The chromatin remains fine in reactive/reparative processes, but nucleoli can be prominent

♦

Microglandular hyperplasia is not distinctly recognized on cytology. Most cells look like normal endocervical cells or may assume repair-like features

♦

Cells derived from lower uterine segment endometrium typically occur as cohesive aggregates (tissue fragments) of a biphasic mixture of glandular and stromal cells (Fig. 1.49). The cell aggregates are large with tubular branched glands that may fold and appear three-dimensional. Feathering and palisading are absent. Cell polarity is retained. The nuclei are smaller and more uniform than those of AIS and have finely granular chromatin

Fig. 1.49.

Lower uterine segment endometrium can mimic AIS. Branching fragment of epithelial and stromal cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

HSIL involving endocervical glands may show feathering; however, it is often restricted to one end of a crowded sheet. HSIL cells are usually arranged in large syncytial aggregates with ill-defined cell borders and loss of polarity. HSIL cells have dense cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with nuclear membrane irregularities. Strips, rosettes, or pseudostratified atypical columnar cells that are characteristic of AIS are not observed in HSIL. Unlike AIS, numerous normal endocervical cells and individual dysplastic squamous cells are typically present in the background in HSIL. Since AIS is much less frequent than HSIL (0.01% compared to 0.2–0.4%), the latter interpretation should statistically be more likely to represent the true cervical abnormality (Figs. 1.50 and 1.51)

Fig. 1.50.

HSIL involving endocervical glands mimicking AIS. Syncytial cluster of HSIL in a tight cluster with rounded contour. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.51.

CIN3; severe dysplasia/carcinoma in situ involving endocervical glands. The endocervical glands are occupied by dysplastic squamous cells extending from the surface (histology, H&E).

Endocervical Adenocarcinoma (Figs. 1.52 and 1.53)

Fig. 1.52.

Adenocarcinoma , endocervical. Columnar cells with eccentric large round to oval nuclei, irregular chromatin, and nucleoli. CP conventional preparation.

Fig. 1.53.

Adenocarcinoma, endocervical. Adenocarcinoma cells with suggestion of a columnar configuration and glandular foundation. The nuclei are elongated and hyperchromatic with irregularly distributed chromatin pattern and nucleoli. The cytoplasm is basophilic and granular. Tumor diathesis is present in the background. CP conventional preparation.

Cytologic Features

♦

Highly cellular specimens that demonstrate isolated single columnar or cuboidal cells and crowded three-dimensional or acinar groupings

♦

The nuclei are round to oval with coarse granular chromatin, irregular chromatin (clearing), and macronucleoli. An increase in nuclear size and nuclear pleomorphism is noted in less differentiated tumors. Multinucleation and mitotic figures may be present

♦

The cytoplasm is more abundant and foamy or finely vacuolated compared to AIS

♦

Necrotic granular (tumor) diathesis is present in approximately 50% of cases

Variants

♦

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) can be a very difficult cytologic diagnosis. In the proper clinical context, the presence of an excessively hypercellular specimen with strips, honeycomb sheets, and three-dimensional clusters of cells with distinct cell borders, abundant lacy cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei (rather than elongated) with coarse granular chromatin, and occasional nucleoli may suggest the possibility

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The features distinguishing endocervical from endometrial adenocarcinom a are shown in Table 1.2

Table 1.2.

Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Versus Endometrial Adenocarcinoma

Endocervical adenocarcinoma a (Endocervical type) | Endometrial adenocarcinoma (Endometrioid type) |

|---|---|

Younger patients | Elderly patients |

Sheets, strips, rosettes, feathering, and cell balls arrangement | Syncytial arrangement |

Larger columnar cells | Smaller cell with indistinct cell border |

Granular cytoplasm with mucin | Amphophilic cytoplasm without mucin |

Stroma absent | Stroma present |

Solitary macronucleoli | Multiple small nucleoli |

Necrotic dirty background | Watery diathesis |

Endometrial Cytology

Cytologically Normal Endometrial Cells (Figs. 1.54 and 1.55)

Fig. 1.54.

Endometrial cells, present in 45 years and older. Tight cluster of small glandular cells with eccentric nuclei and scant cytoplasm. The nuclei are uniformly round with regularly distributed chromatin. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.55.

Endometrial cells, cytologically normal exodus. A tight ball of cells with central stromal cells and peripheral glandular cells. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

Cervicovaginal cytology is a screening tool for SCC and its precursor lesions. It is not a sensitive or accurate screening test for detection of endometrial lesions and should not be used to evaluate suspected endometrial abnormalities

♦

The significance of endometrial cells is in part dependent on the age of the patient, day of last menstrual cycle, menopausal state, and hormonal usage:

Endometrial cells peak at days 4–5 and may persist until days 12–14 of a 28-day menstrual cycle

The presence of endometrial cells after days 12–14 or in postmenopausal women is associated with an age-dependent increased detection of endometrial pathology (endometrial polyp, hyperplasia, or adenocarcinoma)

♦

Changes/lesions that may be associated with endometrial cells include IUD use, hormonal effect, immediate postpartum period, impending or early abortion, acute and chronic endometritis, recent intrauterine instrumentation, endometriosis, polyps, and submucosal leiomyoma

♦

Abnormal shedding of cytologically normal endometrial cells may be associated with a 35–40% risk of endometrial pathology of any kind. There is advancing risk with age. Menopausal status may be omitted or inaccurately documented, especially in patients with irregular or excessive bleeding. The Bethesda system suggests reporting benign-appearing endometrial cells in all women age 45 and greater, regardless of hormonal therapy, to increase the positive predictive value and reduce unnecessary endometrial biopsies

♦

No endometrial sampling is usually done for asymptomatic, low-risk premenopausal women. Postmenopausal women with benign-appearing endometrial cells should have endometrial sampling

Cytologic Features

♦

The cytologic features of endometrial cells are related to their site of origin in the endometrium, menstrual cycle day, the environment into which they are shed, the interval that has elapsed since the cells were shed, the collection method, and the processing techniques:

Endometrial epithelial cells usually present as loose three-dimensional clusters and cell balls. The cells are small and cuboidal to round. The nuclei are round or bean shaped and slightly eccentric with uniform finely powdered chromatin pattern. The nuclear size is similar to that of an intermediate squamous cell nucleus. They have scant amphophilic and often finely vacuolated cytoplasm

Superficial endometrial stromal cells individually resemble, and may be indistinguishable from, histiocytes. They are identified as stromal cells when numerous and loosely clustered. They have round, oval, or reniform nuclei which are usually centrally located but may be eccentric. Their chromatin is finely granular and micronucleoli may be observed

Deep endometrial stromal cells present as loose aggregates late in the menstrual flow. The cells are spindle or oval with ill-defined cytoplasmic borders. The nuclei are reniform or cigar shaped, often with nuclear enfolding (grooves). The nuclear chromatin is finely granular but at times may be hyperchromatic. Small chromocenters may be observed

Exodus represents cell balls composed of central stromal cells surrounded by peripheral larger epithelial cells. Exodus clusters are usually observed on days 6–10 of the menstrual cycle

Atypical Endometrial Cells (AEM ) (Fig. 1.56)

Fig. 1.56.

Atypical endometrial cells. Tight cluster of endometrial cells with loss of polarity, variation in nuclear size and shape, coarse chromatin pattern, and scattered small nucleoli. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

♦

There are no well-defined criteria to separate reactive versus preneoplastic endometrial cells, and atypical endometrial cells are not subdivided into categories

♦

May originate from endometrial polyps, acute and chronic endometritis, endometrial metaplasia, endometrial hyperplasia, or well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade 1). The incidence of adenocarcinoma in women with AEM is significantly higher in women greater than 59 years old

Cytologic Features

♦

Small groups composed of usually 5–10 cells with mild cellular crowding without nuclear pseudostratification. The nuclei are slightly enlarged with mild hyperchromasia, anisocytosis, and small nucleoli. The cell borders are ill defined, and when compared with endocervical cells, these cells have scant cytoplasm, which occasionally is vacuolated

Endometrial Adenocarcinoma (Figs. 1.57 and 1.58)

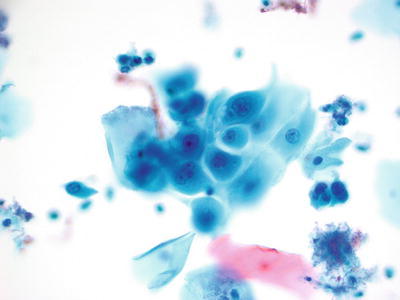

Fig. 1.57.

Adenocarcinoma, endometrial. Three-dimensional cluster of malignant glandular cells with round eccentric nuclei, vacuolated basophilic cytoplasm, and macronucleoli. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.58.

Adenocarcinoma, endometrial. A cluster of pleomorphic malignant glandular cells with eccentric irregular nuclei, irregular chromatin, and macronucleoli. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Cytologic Features

♦

Shedding of neoplastic cells is generally sparse and irregular especially for low-grade tumors. The cell size increases from low- to high-grade tumors. In general, the cells present mainly as three-dimensional clusters of round cells and demonstrate loss of cell polarity

♦

The nuclei are enlarged (greater than 70 μm2) with high N:C ratio. Nuclear crowding and overlapping are typical. The nuclear chromatin is not usually hyperchromatic, but tends to be powdery with parachromatin clearing. Nucleolar enlargement is proportional to grade of tumor

♦

Cells tend to have a scant cyanophilic cytoplasm with fine vacuolization. The presence of intracytoplasmic neutrophils in glandular clusters may raise concern for at least AEM but only provided the associated endometrial cells are cytologically atypical and other clusters of endometrial cells in the Pap test are atypical

♦

In LBC, the endometrial adenocarcinoma cell groups may be more spherical or clustered than CP smears. The nuclei present in these groups may show less visual accessibility due to cellular overlap. The distinction between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma may be more difficult in LBC than CP smears, especially for high-grade tumors

♦

Single or loose clusters of foamy histiocytes and lipophages may be present in the background as well as a watery granular tumor diathesis

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Normal endometrial cells have a round nucleus that is similar in size to the intermediate squamous cell nucleus. There are no cytologic features of malignancy

♦

The cytologic changes of AEM may overlap with those of low-grade endometrial adenocarcinoma. AEM cells maintain cell polarity, the nuclear size is less than that of adenocarcinoma, and there is no tumor diathesis

♦

The cytologic differences between endometrial and endocervical adenocarcinoma are shown in Table 1.2

Other Malignant Neoplasms

These tumors may represent rare or unusual variants of cervical carcinoma or uncommon primaries arising in the uterine corpus or adnexa that appear in the cervical cytology specimens either as exfoliated cells or through direct sampling of tumors

Small Cell Carcinoma of Cervix (Figs. 1.59 and 1.60)

Fig. 1.59.

Small cell carcinoma . Malignant small cells with high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio, molding, and single-file arrangement. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Fig. 1.60.

Small cell carcinoma. Small blue cells with molding and necrosis (histology, H&E).

♦

Uncommon and aggressive tumor of neuroendocrine origin. Almost all cases of small cell carcinoma are associated with HPV type 18 or 16. Small cell carcinoma of the cervix can coexist with adenocarcinoma or SCC

Cytologic Findings

♦

The neoplastic cells are generally small, cuboidal, or round and present as single cells or in small tight syncytial aggregates. The tumor cells have scant cyanophilic cytoplasm, a high N:C ratio, and round to oval nuclei with hyperchromatic and coarsely granular chromatin. Nucleoli are not observed. Nuclear molding, necrosis, and crush artifact are prominent

Papillary Serous Adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1.61)

Fig. 1.61.

Vaginal specimen. Adenocarcinoma, metastatic to vagina from primary ovarian papillary serous carcinoma. Three-dimensional cluster of malignant glandular cells with prominent nucleoli. LBC liquid-based cytology preparation.

Cytologic Findings

♦

Cells are usually shed in papillary aggregates and have all the features of a poorly differentiated carcinoma. Small compact cell balls, elongated groups with peripheral molding, or irregular tight clusters may be identified. Occasionally the central connective tissue core may be seen. Psammoma bodies can be observed

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Papillary serous carcinoma of the endocervix, endometrium, and fallopian tubes/ovaries are indistinguishable. Poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (FIGO grade III) and extrauterine papillary serous carcinoma cannot be distinguished cytologically

Extrauterine Metastatic Adenocarcinoma

♦

The clinical history of a nongynecologic malignancy is essential for an interpretation of extrauterine carcinoma. Most extrauterine carcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas

♦

Ovarian carcinoma is the most common primary site (papillary serous carcinomas). Other primary sites include the fallopian tubes, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and breast. The presence of ascites and patent fallopian tubes increases yield for extrauterine carcinoma

Cytologic Findings

♦

The specimens are generally of low cellularity if the carcinoma spreads via the fallopian tube and endometrium without implantation. The cellularity is high if there is implantation in the vagina or direct spread to the vagina

♦

May be three-dimensional, tubular, spherical, or papillary tissue fragments. The malignant cells are large cells with high N:C ratio, nuclear hyperchromasia, and macronucleoli

♦

Often no specific cytologic features suggest the primary site. Exceptions may include the presence of psammoma bodies (favor ovarian), columnar cells with brush borders (favor gastrointestinal), and cords of cells (favor breast)

♦

Tumor diathesis is generally absent in extrauterine carcinoma, provided implantation has not occurred

Malignant Mixed Müllerian Tumor (MMMT )

Cytologic Findings

♦

Characterized by the presence of two distinct tumor cell populations: a malignant poorly differentiated glandular component with or without squamous differentiation and a pleomorphic spindle or multinucleated sarcomatous component. Heterologous elements are rare and are cytologically difficult to recognize

♦

The malignant epithelial component can shed as single cells or in aggregates, whereas the sarcomatous cells usually occur as single cells and, rarely, in aggregates

♦

Tumor diathesis is usually evident

Lymphoma/Leukemia Cervix

Cytologic Findings

♦

Variable cytomorphology depending on the specific type of lymphoma

♦

There is complete lack of intercellular cohesion among tumor cells. Some of the cells may appear to cluster, but no true aggregates are present

♦

The tumor cell population is generally monomorphic and the lymphoma cells have high N:C ratio. In most lymphoma cells, the cytoplasm is barely visible; however, a minority has a plasmacytoid appearance with more abundant cytoplasm

♦

The nuclear membrane usually shows marked convolutions and may show a nipple-like protrusion. The chromatin is coarse with regular clumps. Nucleoli are not common except in the immunoblastic lymphoma category

♦

The cytologic subtyping of lymphomas is not reliable

Pap Test and HPV Testing

♦

Around 130 HPV subtypes have been described, of which 30 exclusively infect the anogenital area. HPV is divided into low risk and high risk according to their oncogenic potential:

High-risk HPV (HR-HPV) include types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 66. Of the HR-HPV, HPV 16 is found in 50–60% of cervical cancers and HPV 18 in 10–20%. Types 26, 53, 68, 73, and 82 have also been detected in cervical cancer

The low-risk HPV types include 6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, and 89. Of the low-risk types, HPV 6 and 11 are the main causative agents for genital warts

♦

HPV “testing” refers to DNA testing for HR-HPV types. Studies have found no clinical role for low-risk HPV testing in cancer prevention. The management guidelines on the use of HPV testing are based on controlled trials using validated HPV assays. Similar results cannot be assumed when management is based on results of assays not similarly validated. Only HPV tests validated to ensure reproducibility and accuracy in identifying cancer precursors may be used by laboratories. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approved Screening Tests for HR-HPV include:

Hybrid Capture 2 (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD): in vitro nucleic acid hybridization assay with signal amplification and chemiluminescence for the qualitative detection of 13 types of HPV (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68) in cervical specimens. The ALTS studies employed ThinPrep® Pap test and Hybrid Capture 2 and serves as the basis for the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) guidelines

Cervista HR-HPV (Hologic, Bedford, MA): in vitro diagnostic test for the qualitative detection of DNA from 14 HR-HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) in cervical specimens. Cannot determine the specific HPV type present. Uses Invader chemistry, a signal amplification method for detection of specific nucleic acid sequences. This method uses two types of isothermal reactions: a primary reaction that occurs on the targeted DNA sequence and a secondary reaction that produces a fluorescent signal

Cobas 4800 (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA): qualitative in vitro test utilizing amplification of target DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and nucleic acid hybridization for the detection of 14 HR-HPV types in a single analysis. The test specifically identifies types HPV 16 and 18 while concurrently detecting additional HR-HPV types (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68). The Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) trial serves as the basis for the approval of the Cobas 4800 HPV testing

APTIMA HPV and APTIMA HPV 16,18,45 Genotype (AHPV-GT) assay (Hologic, Bedford, MA): in vitro nucleic acid amplification test for the qualitative detection of E6/E7 viral messenger RNA (mRNA) from 14 HR-HPV (16, 18, 31.33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68) in cervical specimens. The APTIMA HPV assay does not discriminate between the HR-HPV types. Testing can be performed on cervical specimens in ThinPrep Pap test vials containing PreservCyt Solution and collected with broom-type or cytobrush/spatula collection devices. The assay is used with the TIGRIS direct tube sampling (DTS) System. The Clinical Evaluation of APTIMA mRNA (CLEAR) study was the pivotal, prospective, multicenter clinical study in the United States to validate the APTIMA HPV assays

♦

The 2013 Cytology Education and Technology Consortium on HPV test utilization provided screening guidelines:

HPV testing is preferred for initial triage for: routine screening in women 30 years and older (as a component of co-testing), ASC-US in women 25 years and older, and LSIL in a women 30 years or older (as a component of co-testing)

HPV testing is also preferred for these preceding results for which co-testing surveillance (without colposcopy) is appropriate: women 30 years or older NILM/HPV positive, and women 25 years and older ASC-US/HPV negative, and women 30 years and older LSIL/HPV negative