(1)

Department of Histopathology and Cytology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, UK

Abstract

In this chapter the appearance of in situ and invasive glandular neoplasms of the cervix and their cytological mimics will be described.

Keywords

EndocervixAdenocarcinoma in situCervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasiaAISCGINAdenocarcinoma of the cervixIntroduction

Although the histological appearance of adenocarcinoma in situ of the endocervix (AIS) was described by Friedel and McKay in 1953, it was not until nearly 20 years later that Barter and Waters provided the first description of the cytological manifestations of AIS in conventional cervical cytology preparations, which were subsequently expanded and refined by other workers, and the cytological appearances suggestive of invasive cervical adenocarcinoma described [1–7]. More recently, defining criteria to separate normal or metaplastic from neoplastic endocervical cells and the cytological appearances in the two most commonly used liquid based cytology systems have also been described [8–14].

Cervical Glandular Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CGIN)/Adenocarcinoma In Situ (AIS)

The cytological appearance of CGIN/AIS in both conventional and liquid-based cervical cytology preparations reflects the histological appearances described in Chap. 3 and it is often the abnormal microarchitecture of crowded cellular groups that first draws attention at routine screening magnification.

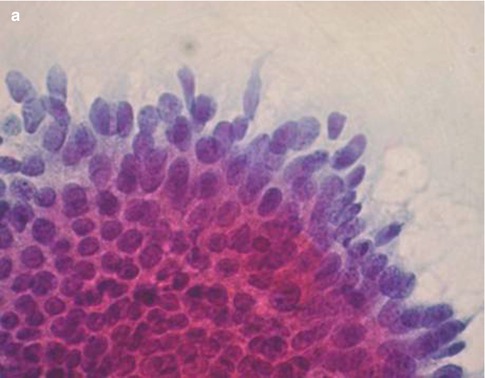

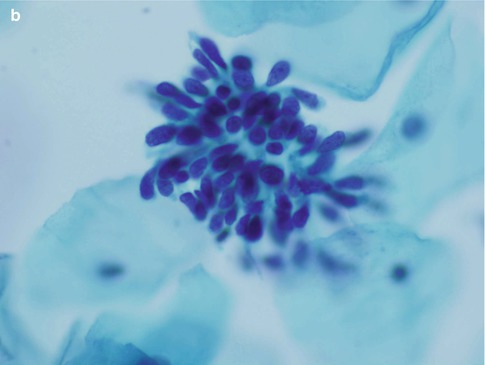

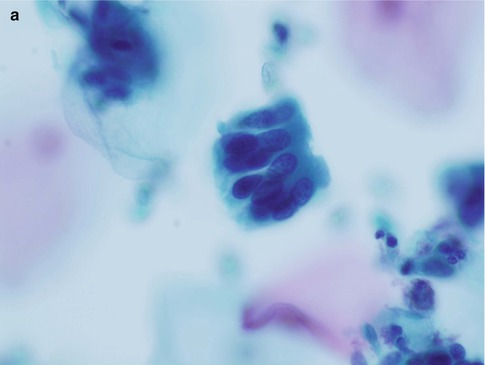

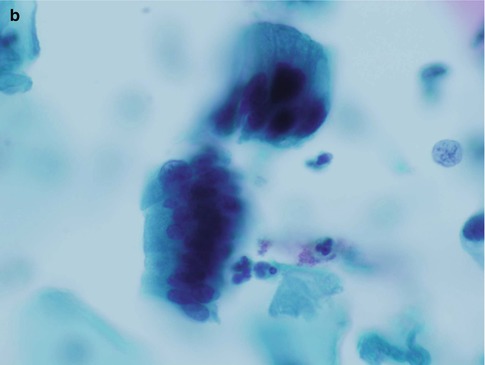

Sheets of exfoliated cells from CGIN present as variable sized groups of crowded cells with frequent overlapping nuclei of uniform size and loss of the “honeycomb” pattern of normal endocervical cells (Fig. 6.1). At the margin of the cell groups there may be disrupted crypt openings and within the cell groups rosette formation, representing abortive attempts at glandular differentiation. Isolated rosettes may also be present (Fig. 6.2). In addition, at the margin of the cell groups, the nuclei of the constituent cells may lie at different levels (pseudostratification) and as a result of partial or complete loss of cytoplasm, bare nuclei or nuclei with tapering delicate cytoplasmic tags project from the crowded cell groups: an appearance first described as “feathering” by Pacey and colleagues in conventional cervical smears (Fig. 6.3). Although this appearance is less common and may be more subtle in liquid based cervical cytology preparations, it may still be a useful criteria to distinguish neoplastic glandular from squamous lesions in hyperchromatic crowded cell groups.

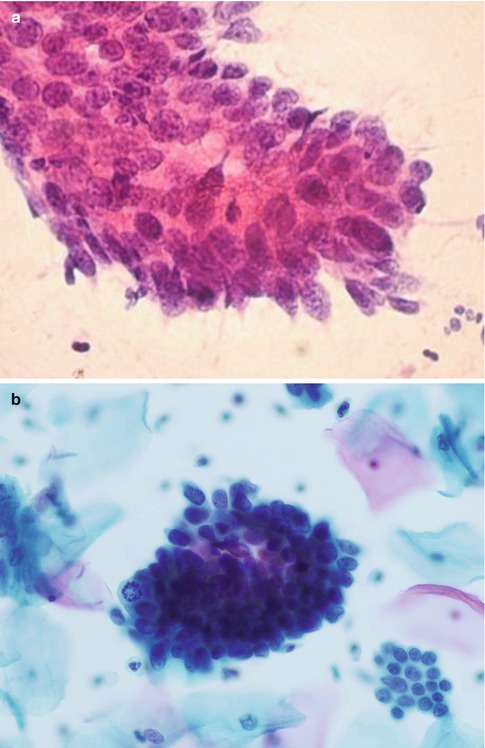

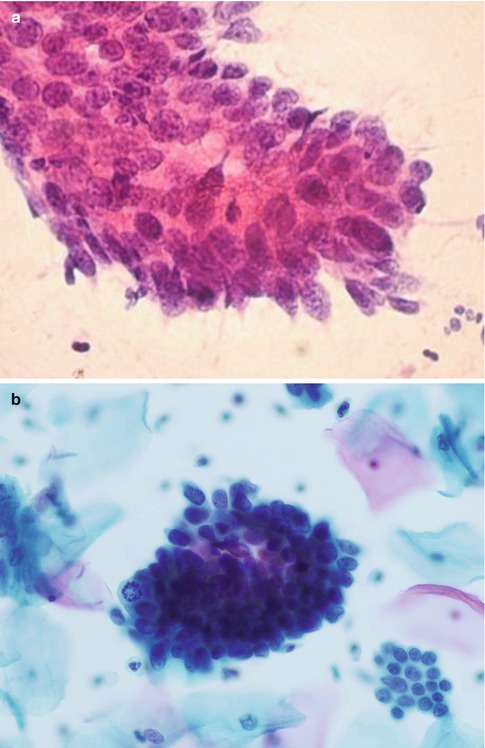

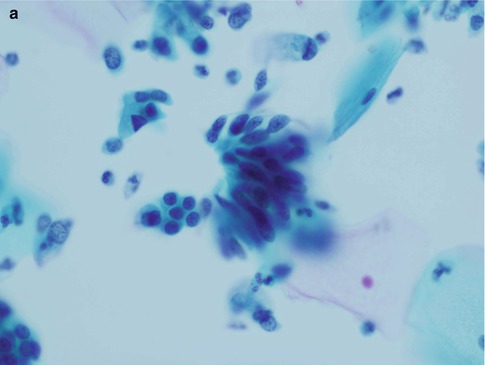

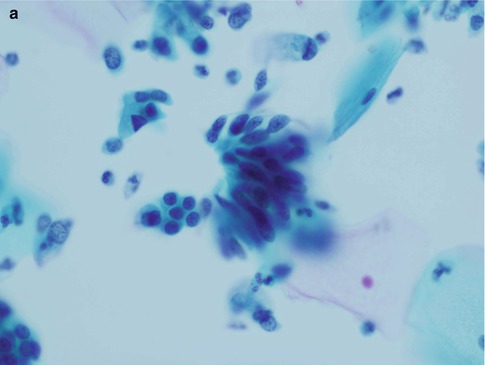

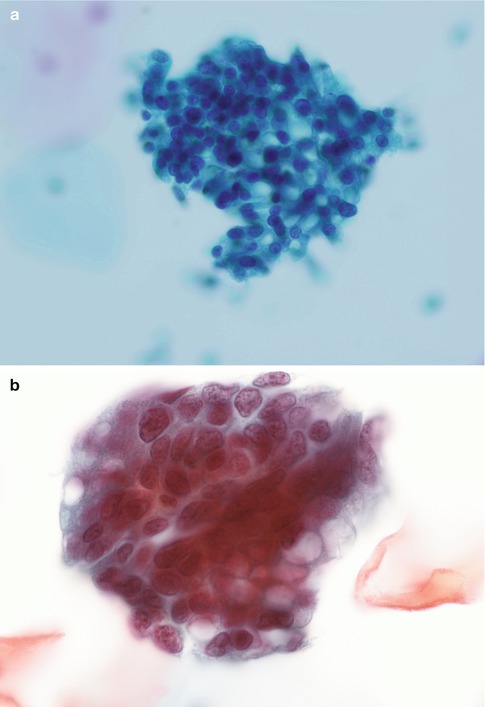

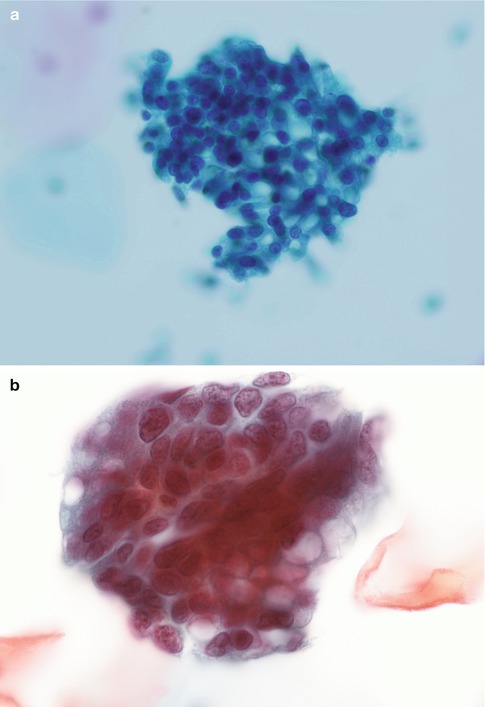

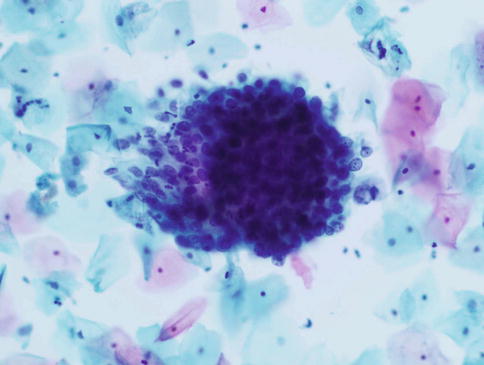

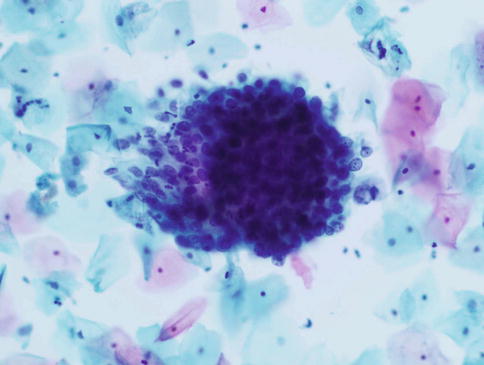

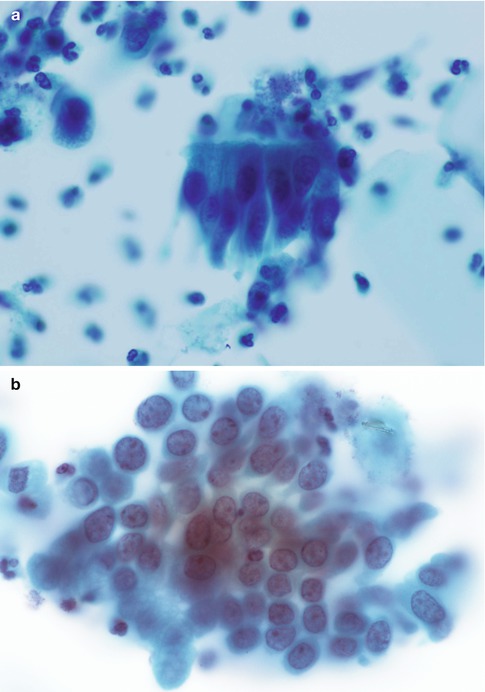

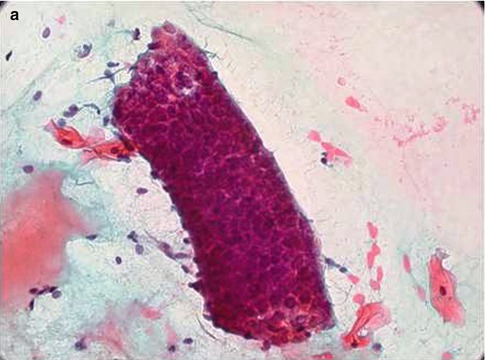

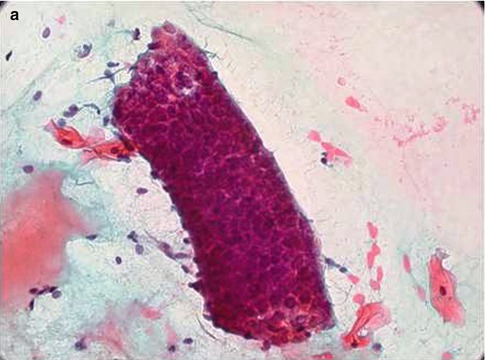

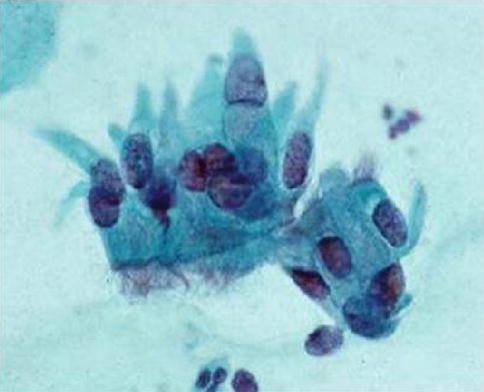

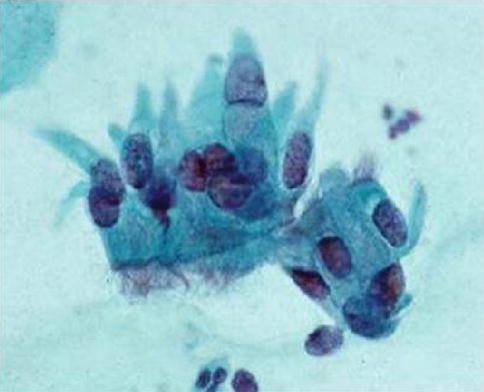

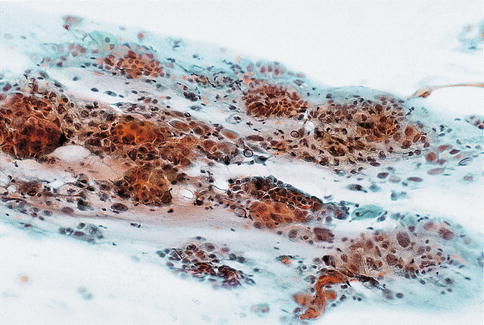

Fig. 6.1

A group of crowded disorganised atypical endocervical cells derived from adenocarcinoma in situ in a conventional cervical smear (a) and a SurePath LBC preparation (b)

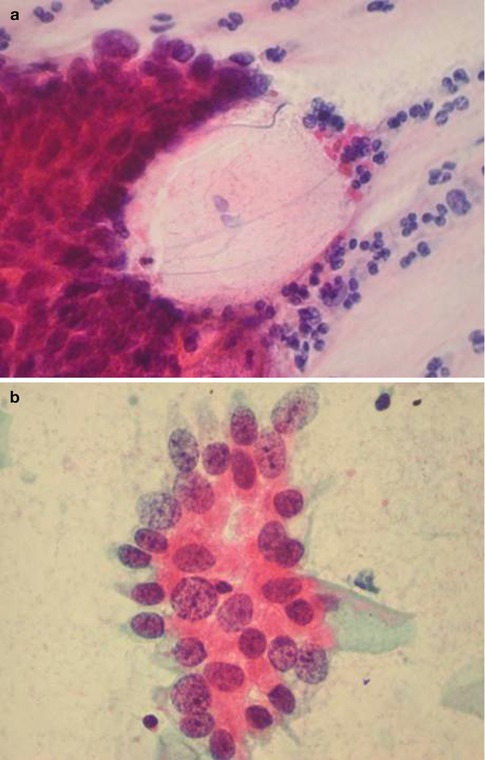

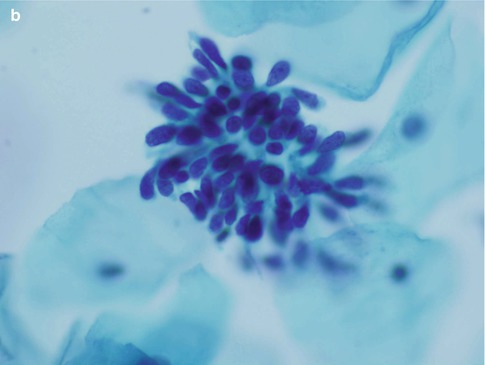

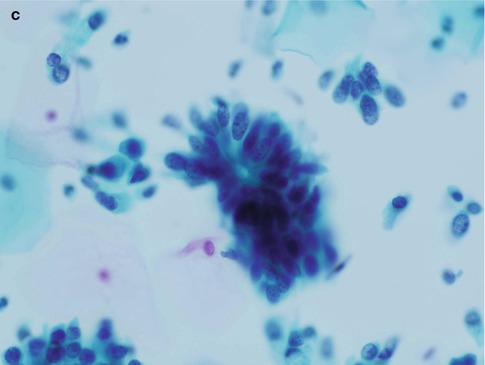

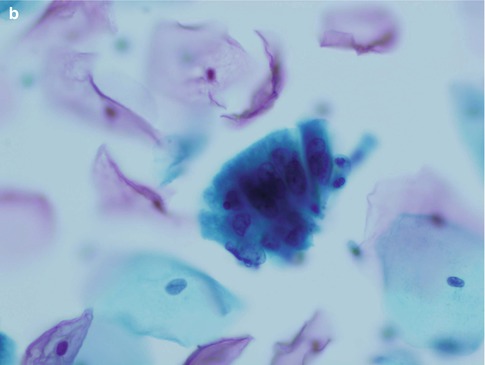

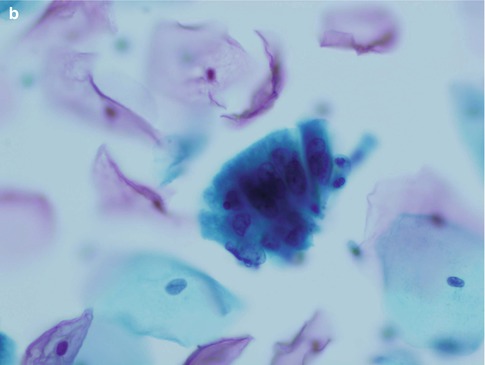

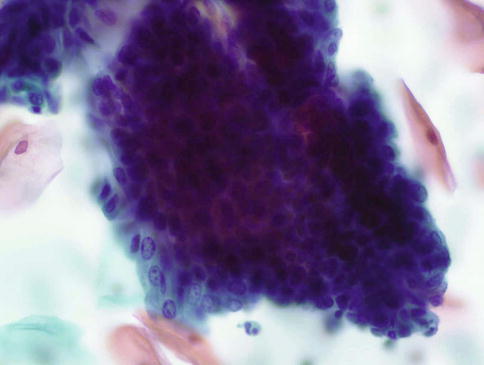

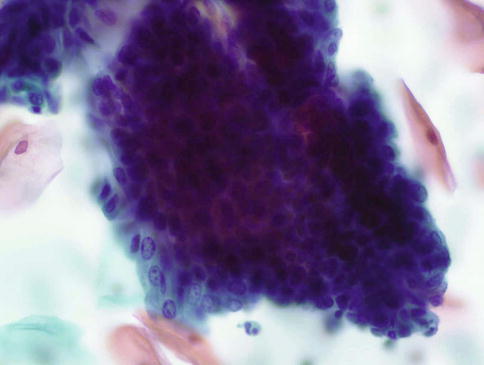

Fig. 6.2

Disrupted crypt opening (‘torn open gland’) at the edge of a group of cells derived from adenocarcinoma in situ in a conventional cervical smear (a) and rosette formation in a conventional cervical smear (b) and a SurePath LBC preparation (c)

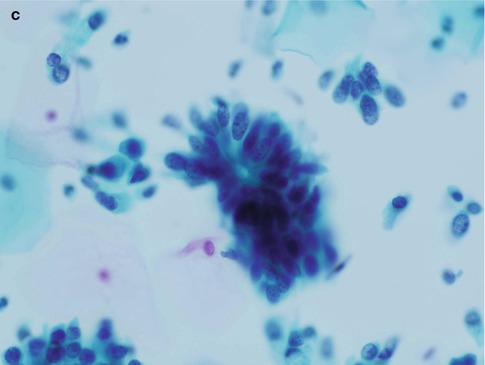

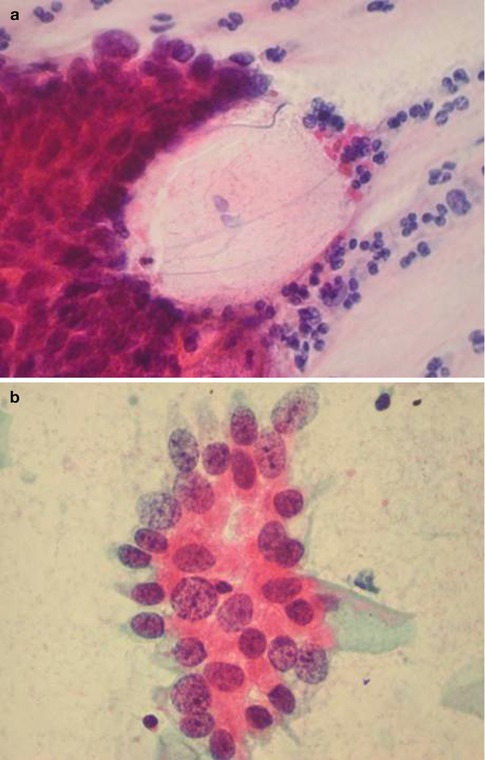

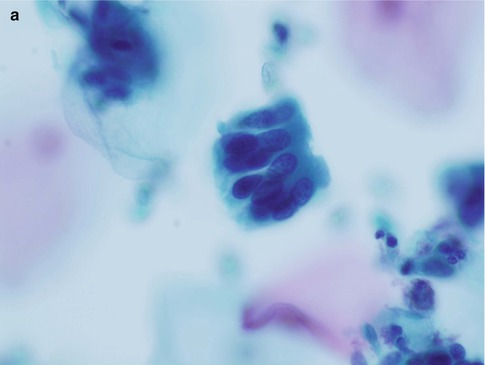

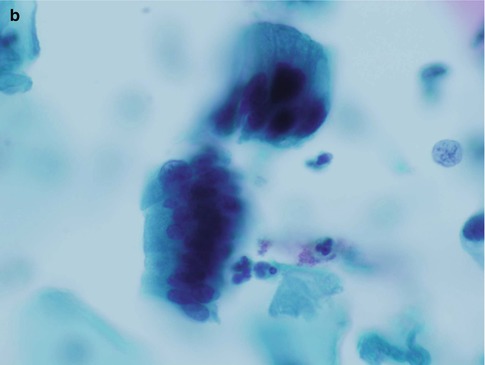

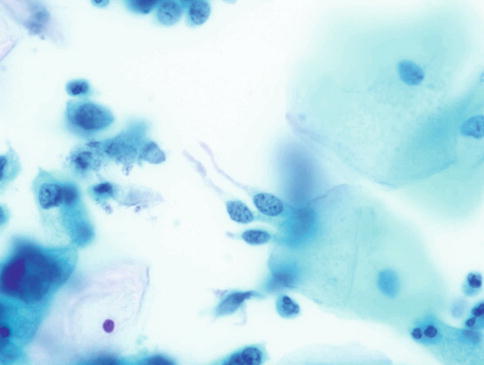

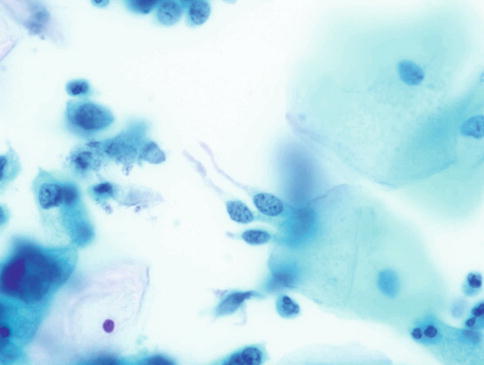

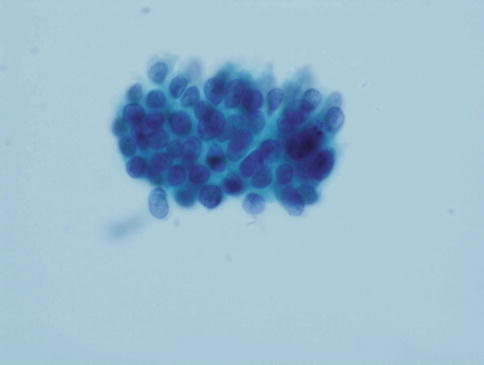

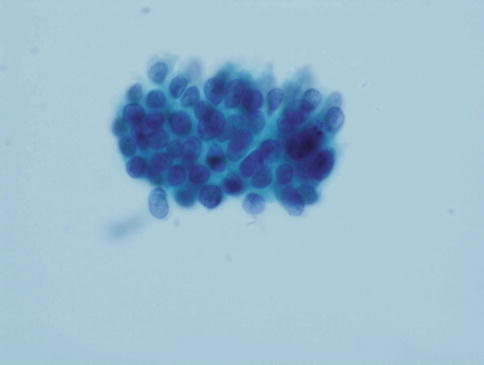

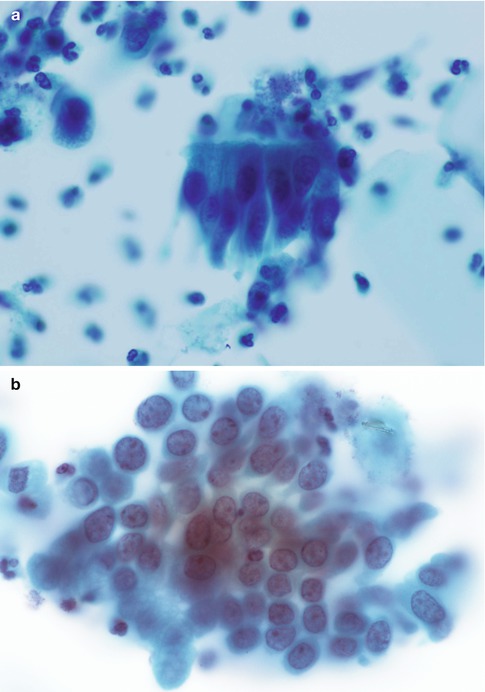

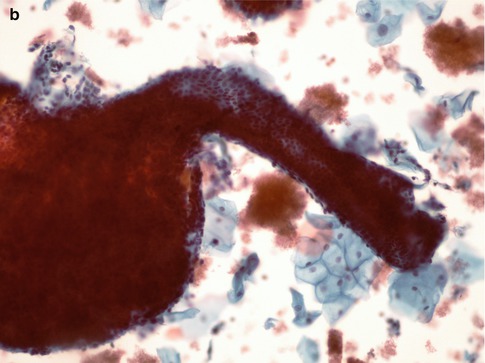

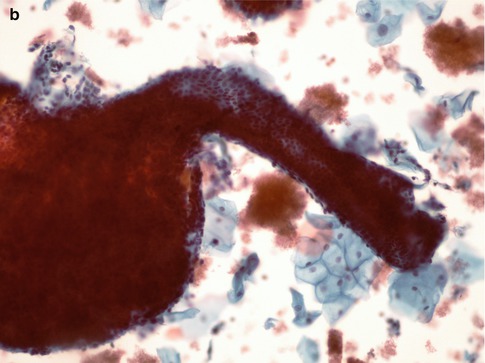

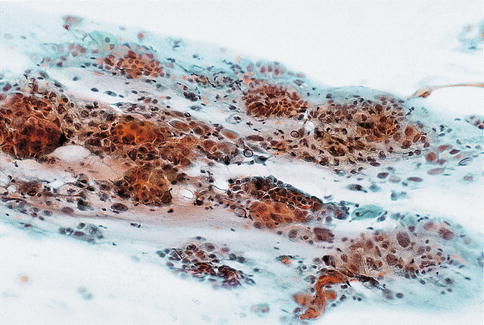

Fig. 6.3

“Feathering” in adenocarcinoma in situ in a conventional cervical smear (a) and a SurePath LBC preparation (b). Note the bare nuclei and nuclei with tapering delicate cytoplasmic tags projecting from the cell group

Cells derived from CGIN may also present as short strips with a straight or slightly curved contour in which there is pseudostratification of nuclei with a common cytoplasmic border (Fig. 6.4). Especially in SurePath liquid based cytology preparations the dyskaryotic nuclei tend to fan out resulting in an appearance resembling a bird’s tail or fish tail (Fig. 6.5).

Fig. 6.4

Strips of cells from adenocarcinoma in situ with characteristic nuclear pseudostratification and a common cytoplasmic border (a, b). SurePath LBC

Fig. 6.5

Slightly curved pesudostratified strips of cells from adenocarcinoma in situ resembling a bird’s tail or fish tail (a, b). SurePath LBC

Isolated or loosely cohesive small groups of neoplastic glandular cells may also be present in the background and as described above frequently have delicate cytoplasm which tends to taper from the nucleus resulting in a so-called “snake and egg” effect (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.6

Neoplastic glandular cells with tapering delicate cytoplasm – “snake and egg” appearance. Note the characteristic fine and coarse granular nuclear chromatin. SurePath LBC

Cell nuclei, whether in individual cells or groups of cells, are usually of similar size to that of normal endocervical cell nuclei, show minimal anisonucleosis, and are oval in shape with smooth nuclear membranes of variable thickness. Nuclear chromatin is of even distribution but varies from fine to coarse granularity resulting in a “salt-and-pepper” appearance. Mitoses and apoptotic bodies are frequently identified in crowded cell groups and may be present in exfoliated strips of neoplastic endocervical cells.

The appearances described above relate to the usual or endocervical type of CGIN. In intestinal type CGIN individual cells with prominent solitary cytoplasmic vacuoles (goblet cells) are present and an extremely useful clue as to the neoplastic nature of the process (see Chap. 3) (Fig. 6.7). In endometrioid type CGIN the overall microarchitectural and cytomorphological features are similar to those of usual type CGIN but the individual cells have small even sized nuclei which are rounded rather than oval [15] (Fig. 6.8).

Fig. 6.7

Intestinal type adenocarcinoma in situ with characteristic goblet cell formation (a, b). SurePath LBC

Fig. 6.8

Endometrioid type adenocarcinoma in situ. A disorganised crowded group of small glandular cells with even sized rounded nuclei. SurePath LBC

Mimics of CGIN

There are a number of conditions which may in part cytologically mimic CGIN and cause diagnostic confusion, reflected in the generally reduced sensitivity and specificity of cytological detection of CGIN compared with CIN [16–21]. Furthermore, CGIN and CIN may coexist resulting in a mixed cytological pattern in cervical cytology preparations [16].

Endocervical Crypt Involvement by High Grade CIN (CIN 2/3) (HSIL)

The cytological appearance of endocervical crypt involvement by high grade CIN has been described by Selvaggi and is similar in both conventional and liquid-based cervical cytology preparations [22, 23].

Exfoliated cells from crypts involved by high grade CIN may present one of two patterns. The type A pattern designated by Selvaggi consists of oval clusters of abnormal cells with smooth cell or slightly irregular borders in which the cells at the periphery are flattened or disorganised and those within the centre totally disorganised often with a spindling or whirling arrangement, in contrast to the residual honeycomb pattern of CGIN; the constituent cells show an increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei with granular chromatin (Fig. 6.9). The type B pattern consists of sheets of columnar cells with peripheral palisading and nuclear pseudostratification, suggestive of CGIN, but with nuclear features of squamous differentiation. The latter is characterised by evenly distributed chromatin or chromatin clumping and clearing, variation in size and shape of peripheral nuclei, irregularity of nuclear outlines with occasional notches and micronucleoli, which contrasts with the “salt and pepper” pattern of chromatin, relatively uniform nuclear size, shape and outline, and prominent nucleoli in neoplastic endocervical cells. Furthermore if palisaded or pseudo-stratified cells are present at the periphery of groups of cells derived from crypts involved by CIN, the cytoplasm is usually intact and dense with smooth edges and does not show the wispy cytoplasmic tags typical of CGIN (Fig. 6.10). Apoptosis and mitoses are clearly visualized in both entities and do not permit reliable distinction.

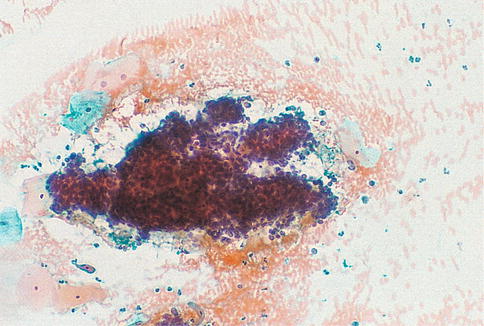

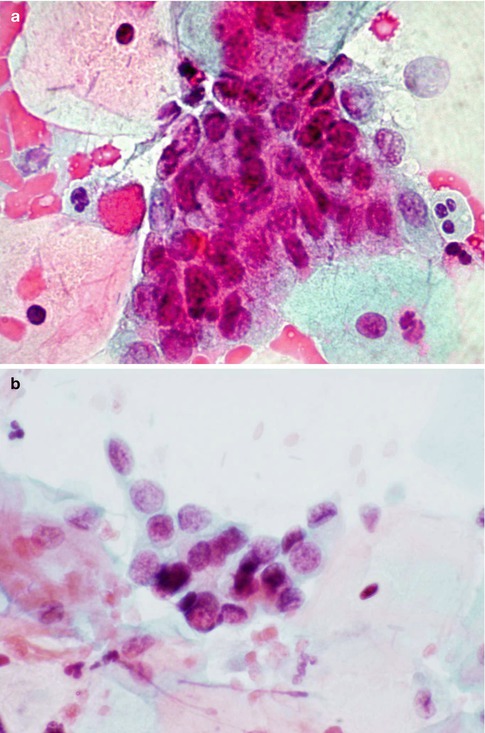

Fig. 6.9

High grade CIN involving an endocervical crypt. An oval cluster of abnormal cells with smooth cell borders. Note the transition from totally disorganised cells in the centre, lacking any honeycomb pattern, to flattened disorganised cells at the periphery. SurePath LBC

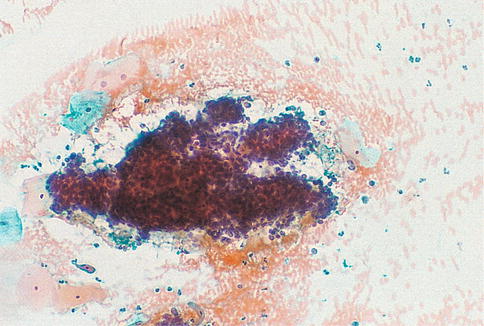

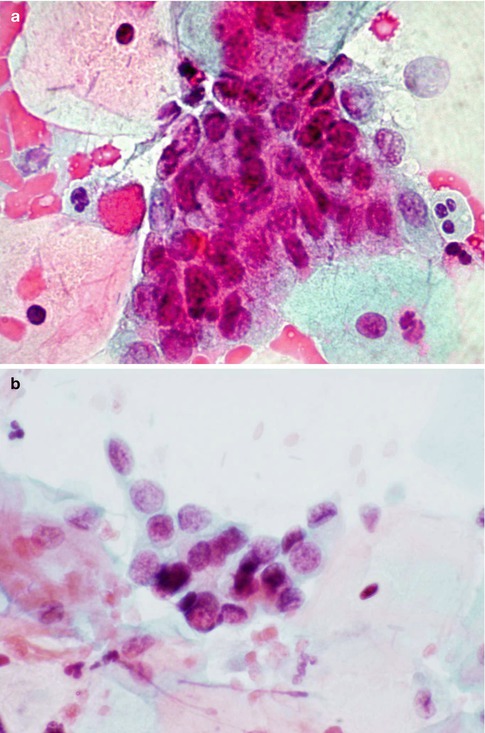

Fig. 6.10

High grade CIN involving an endocervical crypt. Sheets of columnar cells with peripheral palisading and nuclear pseudostratification, suggestive of CGIN, but nuclear features of squamous differentiation, no feathering and intact cytoplasm. SurePath LBC

Inflammatory Change in Endocervical Cells and Benign Endocervical Polyps

In many women with cervicitis or a benign endocervical polyp, cytology samples are entirely normal but in some cases endocervical cells may show reactive changes consisting of crowded cell groups with dense cyanophilic or eosinophilic cytoplasm, maintenance of internuclear spacing, anisonucleosis in round or ovoid nuclei, hyperchromasia and prominent nucleoli [12, 24, 25] (Fig. 6.11).

Fig. 6.11

Reactive changes in endocervical cells viewed in strips (a) and sheets (b)

Occasionally polypoid tissue fragments from endocervical polyps appear in cervical cytology samples, comprising an inner core of numerous small dark stromal cells, covered by a layer of columnar cells with basal nuclei and tissue fragments from lower uterine segment polyps, which typically have a low gland to stroma ratio, present as small vessels running in various directions connected by thin sheets of small ovoid cells with indistinct cytoplasm [26].

Microglandular hyperplasia, as described below, is sometimes seen in cytology samples from a polyp.

Cervical Endometriosis and Lower Uterine Segment Sampling

Although spontaneous endometriosis of the cervix has been described, it is uncommon unless there has been a previous operative procedure such as a loop or cone biopsy or trachelectomy, superficial endometriosis then resulting from direct implantation at the site of injury during a subsequent menstrual period; alternatively endocervical brush samplers or spatulae with elongated tips may directly sample the lower uterine segment and harvest endometrial glands and stroma as intact tissue fragments [24, 27–35].

In conventional and liquid based cervical cytology samples, endometrial cells from the cervix are well preserved and are arranged in large sheets or strips showing gland openings and nuclear stratification respectively composed of cuboidal cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, relatively hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and coarse chromatin; prominent nucleoli and mitoses may be found (Fig. 6.12). These features, together with the exfoliation pattern described, carry the risk that the cells may be mistaken for dyskaryotic endocervical cells. The latter cells, however, typically present as sheets of monotonous cells with crowded overlapping nuclei and the sheets have more striking architectural abnormalities.

Fig. 6.12

Endometriosis of the cervix. A large sheet of cuboidal endometrial cells showing gland openings and nuclear stratification on a haemorrhagic background in a conventional smear (From Smith [84] with permission)

Endometrial stromal cells may also be present, either in loose groups with ragged edges or admixed with the epithelial cells. Stromal cells are oval or round with rounded or reniform nuclei and scanty ill-defined cytoplasm, which is more abundant during the secretory phase of the cycle. The presence of stromal cells enables the diagnosis of endometriosis to be made [24, 28]. In conventional smears in particular the specimen may also be heavily blood stained. Directly sampled tissue from the lower uterine segment consists of tubular structures with well demarcated outlines composed of small uniform cuboidal cells with a peripheral rim of elongated delicate stromal cells orientated along the long axis of the tubular structure; these characteristic features are readily identified at low power routine screening magnification. Such structures are often likened to “elephant trunks” (Fig. 6.13).

Fig. 6.13

Directly sampled tissue from the lower uterine segment in a conventional cervical smear (a) and SurePath LBC preparation (b)

Tubal and Tuboendometrioid Metaplasia

Tubal metaplasia refers to replacement of epithelium at Mullerian-derived sites, such as the endometrial cavity or endocervix, by benign epithelium resembling that of the fallopian tube; in addition, tubal metaplasia frequently includes cells of endometrial type, so-called tuboendometrioid metaplasia. Tubal metaplasia has been found in between 31 and 100 % of adequately sampled cervices removed for both neoplastic and non-neoplastic reasons and tubal or tuboendometrioid metaplasia has been reported in 26 % of cervices removed after cone biopsy [27, 36–38].

Tubal and tuboendometrioid metaplasia tends to be multifocal and involve upper endocervical crypts rather than the lower endocervix and surface epithelium. Therefore it is more likely to be encountered in cervical cytology specimens following the use of brush devices for liquid based cytology sampling [38, 39]. Endometriosis may also occur in the same group of patients, as already described, although it is a less frequent event.

Although not thought to be preneoplastic, it is important that the cytological appearances are recognized and not misinterpreted as indicating endocervical glandular dysplasia: in one study tubal metaplasia accounted for the smear appearances in 76 % of cases in which endocervical glandular dysplasia had been suggested [40].

The cytological appearances in both conventional smears and liquid based preparations have been described in detail [39, 41–43]. All three cell types found in normal fallopian tube epithelium should be present, namely ciliated cells, secretory non-ciliated cells and intercalary cells. Although the proportion of these cells varies greatly between individual samples, ciliated columnar cells with apical terminal bars are necessary for the diagnosis and typically present as aligned groups of cells with well demarcated cytoplasm, which contrasts with the pseudostratified edge, bare nuclei and tapering cytoplasm of AIS (Fig. 6.14).

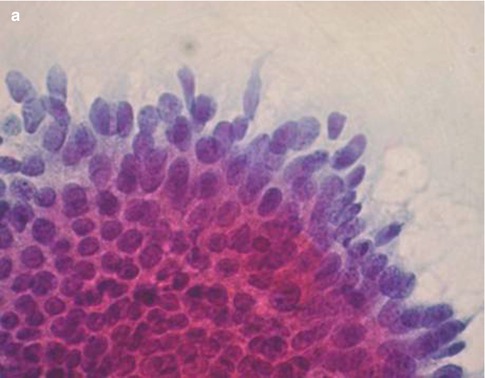

Fig. 6.14

Tuboendometrioid metaplasia in a SurePath LBC preparation. Note the cellular alignment, terminal bars and cilia

The cells, which are smaller than endocervical cells, may be arranged in flat sheets, three-dimensional clusters, small poorly cohesive groups or occur singly. Their nuclei, which are oval, round or elongated and are usually basal in position, tend to be larger than those of endocervical cells and evenly spaced with finely granular nuclear chromatin which is slightly darker than that of endocervical cell nuclei. Nucleoli are more often visible in LBC preparations and are small and single.

Intercalary cells, exclusive to tubal metaplasia but less readily identified in cytology samples, have triangular dark staining nuclei and little cytoplasm, in contrast to the other cells which have varying amounts of granular or vacuolated cytoplasm. Mitoses are rare.

The differential diagnosis includes cervical endometriosis, endometrial cells from the lower uterine segment, microglandular and reserve cell hyperplasia, ‘reactive’ endocervical cells, and dyskaryotic cells from CIN 3 involving endocervical glands. Cilia are usually a feature of benign endocervical cells although a solitary case has been reported of histologically confirmed ciliated adenocarcinoma of the cervix with prior liquid-based cervical cytology showing atypical, ciliated glandular cells that initially raised the diagnostic consideration of tubal metaplasia [44].

Microglandular Hyperplasia

The cytological appearances of microglandular hyperplasia reflect the histological appearances described in Chap. 2 and are characterised by bidimensional or tridimensional cellular clusters made up of cubic or cylindrical glandular cells with vacuolated cytoplasm; basaloid cells with dense cytoplasm, corresponding to immature squamous metaplasia; and subcylindrical reserve cells with small, round nuclei and scant cytoplasm. The clusters also show microlumina or fenestrated spaces, preserved polarity and absence of nuclear peripheral dispersion [45] (Fig. 6.15). Microglandular hyperplasia is a very common condition but is only likely to cause cytological confusion with endocervical or endometrial neoplasia in the most florid papillary forms [39, 46–48].

Fig. 6.15

Microglandular hyperplasia of the cervix in a SurePath LBC preparation. Small groups of glandular cells of variable size with bland nuclear features and abundant focally vacuolated cytoplasm (Courtesy of Dr C Waddell, Birmingham Cytology Training Centre)

Arias-Stella Change

Interpretative problems may arise during pregnancy if the endocervical glandular epithelium undergoes the type of extreme hypersecretory activity known as Arias–Stella change; it can also occur in other hyperprogestational states such as gestational trophoblastic disease and with high dose progestogen or ovulation inducing therapy [49].

The cytological features have been described in single case reports, and in one of these the cervical Arias-Stella reaction was associated with a cervical pregnancy [50, 51]. The atypical glandular cells occur singly, in syncytial clusters and cohesive sheets and are characterised by cyto- and karyomegaly, a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, round to oval nuclei with finely granular or smudgy chromatin imparting a ground glass appearance, frequent intranuclear inclusions, and vacuolated or dense variable staining cytoplasm. Arias-Stella cells may be misinterpreted as malignant glandular cells if the history of pregnancy is not known [52].

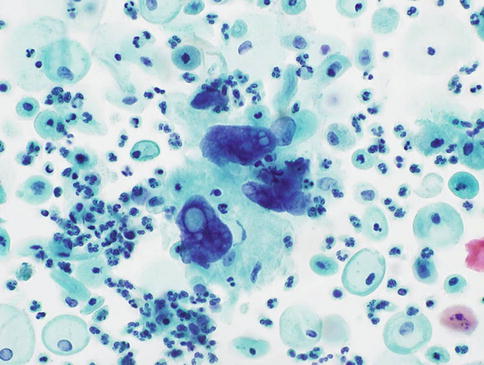

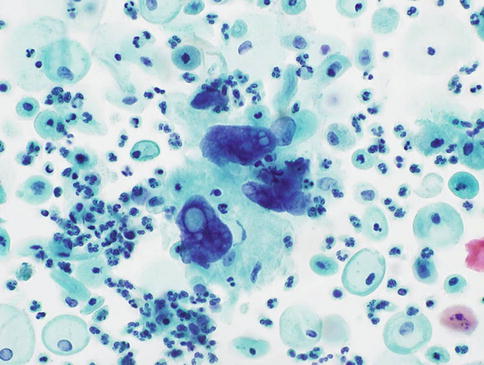

Radiation Associated Changes

Although the cytological changes in cervical squamous cells after radiation therapy have been well described, the literature on the alterations in endocervical cells in response to radiation therapy is very limited. Frierson et al. studied the effect of radiation therapy for cervical cancer on endocervical cells in brush specimens at various times following treatment. Endocervical cells appeared as single cells or clusters lacking the honeycomb appearance of normal endocervical cells with lavender, mucin-filled cytoplasm. In samples taken within 6 months of treatment, the majority of endocervical cells were enlarged but usually had a normal nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio although the nuclei varied in size and had coarse chromatin, large nucleoli and were frequently multinucleated. Repair cells and multinucleated histiocytes were seen in 83 and 61 % of samples, respectively. Each of these cytological findings was less apparent in follow-up smears taken more than 6 months after the completion of radiotherapy. Awareness of these cytological changes in endocervical cells after radiation therapy should prevent the overdiagnosis of cancer in follow-up endocervical brush specimens [53] (Fig. 6.16).

Fig. 6.16

Radiation change in endocervical cells in a conventional smear. Disorganised clusters of cells with loss of the normal honeycomb pattern, anisonucleosis, nucleolar enlargement, occasional multinucleation and abundant cytoplasm (From Waddell and Chandra [85] with permission)

Stratified Mucin Producing Intraepithelial Lesion (SMILE)

To date there are no published accounts of the appearance of this entity in cervical cytology preparations, but a personal review of conventional and SurePath liquid based cervical cytology specimens that preceded the diagnosis of SMILE has identified hyperchromatic crowded groups of glandular cells with focal fine cytoplasmic vacuolation consistent with origin from SMILE (Fig. 6.17). These groups of cells were often associated with neoplastic squamous or endocervical glandular cells consistent with origin from CIN and CGIN respectively, which is frequently found in association with SMILE [54].

Fig. 6.17

Features consistent with origin from SMILE in a conventional smear (a) and SurePath LBC preparation (b). Crowded groups of neoplastic glandular cells with fine vacuolated cytoplasm

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree