Summary by Joseph Westermeyer, MD, MPH, PhD

37

Based on “Principles of Addiction Medicine” Chapter by Joseph Westermeyer, MD, MPH, PhD, and Marion Warwick, MD, MPH

DEFINITIONS RELATED TO SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

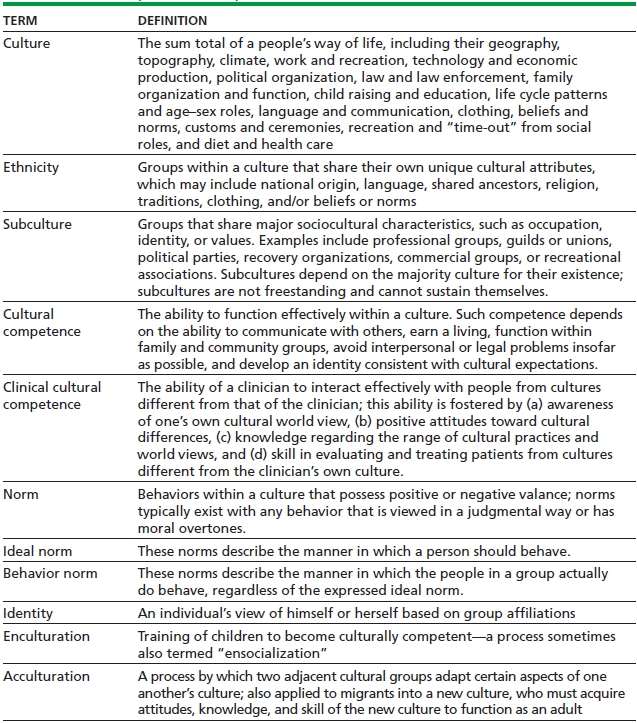

Several concepts related to culture are helpful in guiding addiction specialists in understanding the role of culture in contributing to, as well as alleviating, substance use disorders (Table 37-1).

TABLE 37-1. DEFINITION OF CULTURE-RELATED TERMS WITH UTILITY IN UNDERSTANDING, ASSESSING, AND TREATING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

CULTURE AND PATTERNS OF SUBSTANCE USE AND ABUSE

Cultures prescribe or forbid the use of various psychoactive substances. For example, the Jewish and the Roman Catholic religions require the use of alcoholic beverages at specific ceremonies (e.g., Passover dinner, Catholic mass). On the other hand, cultures and ethnic groups associated with Islam and certain Christian sects forbid alcohol drinking.

A review of modal ethnic patterns of substance use and abuse in the United States may be helpful to clinicians unfamiliar with trends outside of their own communities or ethnic groups. However, these stereotypes may be misleading for the following reasons:

- Within any major group, there can be considerable differences among subgroups over time. For example, patients seeking relief from chronic pain in medical facilities over the period 1990–2010 were at increased risk to iatrogenic opioid addiction.

- If a subgroup manifests actual substance use (its behavioral norm) that differs from its socially prescribed use (its ideal norm), then the group is apt to manifest widely diverse use of that substance (abstinence to heavy and problematic use).

- Rates of substance abuse may change with the generations since immigration to the United States. For example, American-born Hispanics have had a higher risk of alcohol use disorder compared to foreign-born immigrant Hispanics. Migration undermined previous ideal norms, replacing them with an indigenous American norm that fostered their higher rates of alcohol use disorder.

- Sociocultural changes within ethnic groups can affect the pattern of substance use and abuse over time. For example, increased acceptance of cannabis use among younger generations has resulted in legislative changes fostering diverse normative use in various states. The absence of an agreed-upon ideal American norm (or even single-state norm) is an unstable circumstance apt to change to a new steady state or remain unstable and pathogenic.

Clinicians must conduct individual assessments for each new patient, while avoiding stereotyping. Failure to do so will result in both missed diagnosis (in patients from groups with low rates of substance abuse) and overdiagnosis (in patients from groups with high rates of substance abuse).

CULTURAL ASPECTS OF CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

The first step in conducting a cultural history consists of asking patients about the ethnic origins of their parents and grandparents. This would include their place of birth, national origin, language learned at home, migrations, roles and affiliations in the ethnic community and in the community at large, educational experiences, and marital history.

The second step consists of assessing the family’s overall enculturation of the patient in his or her ethnic groups of origin. Of note here, parental substance abuse can disrupt a healthy identity formation and undermine cultural competence.

Adoption or foster home placement can affect ethnic affiliation and identity, if the new parents differ in their ethnic origins from the biologic parents. Adopted children manifest higher rates of disorder in adulthood as compared to nonadoptees.

The developing child’s enculturation can affect the use of psychoactive substances. During late adolescence or early adulthood, the patient may have chosen to relocate away from the family/ community of origin to go to college or to marry cross-culturally, for example. Learning to live in another culture can involve stressors that may precipitate excessive substance use.

SUBSTANCE-SPECIFIC HISTORY

- Observations of role models: What substances did the parenting adults use in the home or outside the home?

- Socialization into psychoactive substance use: Who first taught or guided the patient’s use of psychoactive substances? Did this occur in the home or with peer groups?

- Early experience with substance use: Who determined the substances, occasions for use, dose, and patterns of use? How did use assist coping in the family, in school, etc.?

- Linkage with other developmental tasks: Was the patient learning other developmental tasks at the same time?

- Even if one parent has a substance use disorder, sustaining family rituals (such as daily dinners together, weekly church attendance) reduces phenotypic disorder in the offspring.

SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER AND PATIENTS’ CULTURAL FUNCTION

The relationship between substance use and social performance is a complex one. Psychoactive substance use may foster social coping, at least initially. Nonproblematic use of psychoactive substances can be a manifestation of successful enculturation. Over time, substance use disorder generally undermines cultural performance.

Loss of social coping and competence during the course of substance use disorder is a common feature in all cultures. Examples of status loss include the following:

- Marital status, that is, separation and divorce

- Employment status, that is, jobs of brief duration, longer periods of unemployment, loss of productivity, and decreasing wages

- Housing, that is, living with friends who abuse substances, living alone, homelessness, institutional placement, and incarceration

- Community participation, that is, alienation and isolation from family events, and cessation of participation in rituals and celebrations

- Friends, that is, most friends use substances heavily

- Legal, that is, breaking laws related to driving under the influence, drug possession, property, and violence

- Financial, that is, reduced finances, inability to pay bills, and bankruptcy

The addiction subculture may constitute a welcome identity group to a person who is estranged from family and other groups. Young persons who have failed to achieve social competence in their community of origin may drift toward the affiliation and identity proffered by a drug subculture.

CULTURE, TREATMENT, AND RECOVERY

Substance Use Disorder and the Intimate Social Network

Social network reconstruction can compose a potent means of intervening in the addiction process and then providing support during recovery. A key element involves elimination of active substance abusers from the network, with retention of those committed to the patient’s ultimate recovery. Reciprocity, honesty, and mutual trust constitute the foundation of the intimate social network, normally consisting of 20 to 30 divided into four or five groups (e.g., household, close relatives, work group, avocational group, neighbors, and/or friends). Early on, therapy and mutual help groups, clinicians, or pets may function as part of the person’s intimate social network.

Cultural Recovery in Substance Use Disorders

A number of strategies have proven useful in social network reconstruction during recovery:

- Joining a recovery group whose members are also looking for new associates (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Rational Recovery)

- Joining a group that shares similar interests (e.g., hiking or writing club)

- Joining a charitable organization or a social group with a charitable purpose (e.g., Red Cross)

- Volunteering at a health care facility, a school, or similar facility (e.g., food shelf, shelter)

- Returning to a group or organization from the past, such as an ethnic association or church group

- Going back to school or taking a job that leads to new contacts

These strategies will lead to affiliation with new people and groups, affording the recovering person a new lease on life. These strategies replace the groups associated with psychoactive substance use disorder in the person’s previous life.

A difficult task may lie in building bridges back to relatives and family members. These people have probably been hurt or alienated by past addiction-related behaviors. Frequently, they have come to distrust the recovering person. He/she should expect a long period of rebuilding the lost trust, a year or longer. If the recovering person undergoes a series of slips or relapses—common in the early months of recovery—this can reaffirm the family’s worse fears. Fortunately, for those involved in Twelve-Step work, several of the steps prepare the recovering person for making amends to family members and former friends who have suffered from the consequences of one’s substance use disorder.

Culture-Specific Treatment

Therapies specific to particular cultures, ethnic groups, nationalities, and religions can contribute to recovery from substance use disorders. Some of these interventions are ceremonial in nature, such as healing or spiritual rebirth rituals. Pharmacotherapies can play pharmaco-cultural roles during rehabilitation. For example, clinicians can provide disulfiram to recovering alcohol-dependent patients who will be exposed to alcohol use in their home communities. Taking disulfiram can be an acceptable excuse for not participating in a group-drinking activity instead of being viewed as a rejection of a friendly cultural event. Naltrexone can protect former opioid addicts who may encounter a high-risk situation with ethnic peers.

Some culture-related groups may not specifically address substance use disorder but can nonetheless support recovery.

KEY POINTS

1. Disparity between ideal and behavioral norms, as it applies to substance use, can result in outcomes that are costly to many individuals as well as the society and culture at large.

2. Clinicians can increase their effectiveness by understanding the cultural elements that the patient brings to the clinic. This task begins with understanding the patient’s enculturation from childhood to young adulthood and acculturation to substance use disorder.

3. Current and past cultural affiliations can be helpful in devising a successful recovery plan. Assessing the patient’s intimate social network is an important first step.

4. Cultural resources and traditions can serve clinicians and patients in the challenging process of recovery.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Substance use disorder can undermine the normal intimate social network in which of the following ways?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree