14 Critical care

Severity of illness scoring systems

• Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) rates the most deranged values in the first 24 hours of ICU admission, of 12 physiological variables. The total score is added to two further scores for age and chronic organ insufficiency. APACHE III has added additional variables. It is best validated in the USA.

• Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II) is significantly simpler than the APACHE III system but its applicability has been questioned.

Initial assessment: ABCDE

• The patency of the upper airway should be assessed by looking for any visible obstruction, listening for stridor or silence, and feeling for air movements. If the airway is partially or completely obstructed, institute a jaw thrust and/or chin lift manœuvre. Check whether the patient is at risk of cervical spine injury and, if so, institute immobilization precautions. If airway patency remains suboptimal, carefully insert an oral or naso-pharyngeal airway adjunct, paying attention to size and effectiveness.

• Administer oxygen at the highest available concentration. Assess the breathing by looking for symmetrical or asymmetrical movements of the chest rising and falling, listening for breath sounds and feeling for any chest movement.

• Simultaneously feel for a carotid pulse and, if present, obtain a BP measurement as soon as practical. If there is no pulse, call for assistance, initiate chest compressions and follow basic and advanced life support algorithms (p. 704, 705). If there is a pulse, but no respiratory effort, call for assistance and supply rescue ventilation, ideally with a bag mask valve system connected to high-flow oxygen. Again, follow life support algorithms. If there is some respiratory effort, determine the adequacy by clinical examination, by attaching a pulse oximeter and, if practical, by obtaining an arterial blood gas (ABG) specimen. Be aware of the limitations of pulse oximetry, especially in hypotensive patients. Arterial blood needs to be sampled into an anticoagulated syringe and any air in the sample should be expelled before the sample is safely capped. The sample should be analysed immediately or transported in ice to minimize cellular metabolism in the sample from consuming oxygen and producing carbon dioxide.

Guidelines for initial and daily patient assessment

Initial assessment

• Age, number of days on the unit

• A brief history and update. This should be comprehensive, chronological and concise, and should include:

• Examination. Full detailed examination should be made of all systems, particularly cardiovascular and respiratory, and level of consciousness (p. 624).

Daily investigations

• Full blood count (FBC), clotting (including fibrinogen if coagulopathy is suspected), urea and serum electrolytes (U&E), liver biochemistry, troponin T (or I), calcium, phosphate, albumin, magnesium and glucose should all be documented on a flow chart.

• Patients receiving once daily aminoglycosides and/or continuous infusions of glycopeptides (vancomycin) require daily random blood levels.

• Patients receiving digoxin, aminophylline or phenytoin may require frequent blood level monitoring. As many critically ill patients have markedly reduced serum protein levels, especially albumin, total drug levels that would normally be considered sub-therapeutic or therapeutic may actually be toxic.

• If a patient is likely to require blood products or is going to theatre, ensure that a serum sample is, or has been, sent to the blood bank.

• Screening swabs for colonizing multi-resistant bacteria, in particular meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), are usually sent on admission and on a fixed day of the week thereafter.

• Patients receiving mechanical ventilation may require a daily CXR (preferable erect) during the acute phase of their illness and after any relevant procedures, such as central venous line insertion or percutaneous tracheostomy, have been performed.

Radiological investigations

Some radiological investigations may require the need for IV and/or oral contrast. Most IV contrast agents are nephrotoxic. The mainstay of prevention is good hydration. An additional bolus of an appropriate crystalloid is often required prior to giving the contrast agent. IV N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is used (p. 686) as a prophylactic agent against contrast-induced nephropathy. Prophylactic pre-procedural haemofiltration appears to be effective in patients with severely diminished renal function.

Discharge from the critical care environment

• Ensure that a concise but comprehensive discharge summary is completed prior to the patient’s discharge. This should include diagnosis, clinical state, and drug and nutrition therapy.

• Speak to a senior member of the team who will be taking over the care of the patient, emphasizing any continuing problems and the current management plan.

Dying patients and end-of-life care

• In the terminal phase of a patient’s illness, ensure optimal palliation of any/all sources of distress. Ensure that the family are fully aware of the situation.

• After discussion, withhold/withdraw any unnecessary interventions, including continuous monitoring.

• If uncertain how to complete the death certificate, discuss this with a senior colleague. In the UK, many patients will require discussion with the coroner prior to completion of the death certificate.

Transportation of the critically ill patient

• The team escorting the patient must ensure that all necessary equipment is taken on the transfer, including sufficient supplies to deal with all predictable adverse events. In particular, the quantity of oxygen and battery power required for ventilators, monitors and infusion pumps must be in place.

• Patients who are intubated should always be escorted by a doctor with established airway skills and a nurse.

• Try to minimize the amount of equipment taken with the patient. For example, disconnect from feeding pumps and non-essential infusions.

General considerations for patient care in the critical care environment

• Always introduce yourself to patients and their visitors, and explain what you are about to do. The patient’s comfort and dignity should be everybody’s priority; be conscious of the loss of the patient’s privacy and autonomy.

• Review the effectiveness of management plans at frequent intervals. If you initiate or change something, record it in the notes/chart and decide when you will need to review the patient’s response.

Infection control

• Before entering a critical care environment, remove white coats and jackets. Roll up sleeves to above the elbow and remove all hand and wrist jewellery. Wash hands and/or use an alcohol gel-based disinfectant.

• Before approaching the patient, hands should be washed or disinfected, and a plastic disposable apron or non-sterile gown and non-sterile gloves should be put on. When finished with a patient, remove gloves/gowns/aprons and wash or disinfect your hands again.

• To avoid cross-contamination between patients, all equipment should be dedicated for specific bed space use only.

Patient care

• To prevent passive aspiration and enhance respiratory mechanics, all sedated patients should be positioned at least 30° head up. As soon as practical, sit patients out of bed for a portion of every day. Prescribe a simple eye ointment 6-hourly for all unconscious, sedated and/or mask/helmet-ventilated patients. Check the eyes daily for injury or inflammation in sedated or unconscious patients.

• Always examine the mouth and nose of patients with endotracheal and naso-gastric/naso-jejunal tubes. Look for signs of pressure necrosis, oral colonization and sinusitis. Start a chlorhexidine mouthwash with or without oral nystatin (topical antifungal) and discuss changing the offending tube. Topical antiseptics are increasingly being adopted as primary prophylaxis and added to existing care bundles.

Gastrointestinal care

• Oro-/naso-gastric tubes. All intubated patients, those receiving mask/helmet positive pressure ventilatory assistance and any other patient not able to eat should have either an oro-gastric or a naso-gastric tube.

• Stress ulcer prophylaxis. This is used for patient who are not receiving naso-gastric feeding, are shocked or on vasopressors, have a coagulopathy (including uraemia) or are anticoagulated, or are receiving gastric mucosal irritants, e.g. steroids, NSAIDS. Patients with burns/polytrauma or those who have had prolonged intubation and are sedated should also receive prophylaxis.

• Regimen. Oral ranitidine 150 mg 12-hourly; IV ranitidine 50 mg 8-hourly is given (reduce to 12-hourly in renal failure) if the enteral route is unavailable.

• Bowel care. Constipation and diarrhoea are common complications of critical illness and most patients benefit from stool softeners, e.g. sodium docusate 200 mg twice daily, and mild aperients, e.g. sennakot 5–10 mL twice daily. Osmotic laxatives, e.g. lactulose, are avoided, as they can significantly contribute to bowel gas formation.

Nutritional support

Early enteral feeding

• Early initiation (within 12 hours) is the significant nutritional factor influencing clinical outcome, as ‘late’ feeding (i.e. feeding commenced within 36 hours of admission) is associated with increased gut permeability and an increase in late multi-organ failure.

Prokinetic therapy/enteral feeding failure

• If delayed gastric emptying is present (gastric aspirates > 200 mL after 4 hours), commence prokinetic therapy, e.g. metoclopramide 10 mg IV 8-hourly; erythromycin 250 mg IV 8-hourly is an alternative.

• If enteral feeding cannot be established within 12 hours of admission, use a hypertonic glucose IV infusion, either 25 mL/hour of 20% or 10 mL/hour of 50% into a large vein.

Maintenance fluids — IV and enteral

Assessing the adequacy of fluid replacement

• Achieving the target balance may require regular low doses or continuous infusion of loop diuretics or renal replacement therapy.

• Serum concentrations of sodium and chloride are monitored. Both tend to accumulate as a result of IV fluids and drugs, e.g. piperacillin. Iatrogenic hyperchloraemic acidosis is a common problem.

Packed red cell transfusion

• The optimal haemoglobin (Hb) concentration is a balance of rheology and oxygen-carrying capacity. A target value is usually set at 8–10 g/dL, even in patients with critical myocardial or other organ ischaemia.

• A transfusion trigger of 7.5 g/dL is common. Most blood gas analysers are significantly less accurate at Hb measurement than formal haematology laboratories (errors as much as ± 2 g/dL).

• Try to minimize iatrogenic losses, in particular from blood sampling and during line insertion. Be conscious of the effects of iatrogenic haemodilution.

• Transfusion is not a benign intervention. Stored red blood cells become 2,3 diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG)-depleted, resulting in higher O2 avidity, which causes a leftward shift in the oxygen dissociation curve, i.e. a reduction in oxygen release to the tissues. In addition, cells lose their highly deformable biconcave morphology and come to resemble spiky balls, which fail to enter capillaries and can become impacted, obstructing the micro-circulation. There is also the potential risk of disease transmission and allergic reactions.

Glycaemic control

• There is evidence now to suggest that tight glycaemic control (blood glucose levels between 4.0 and 6.0 mmol/L) in all critically ill patients is detrimental; instead, the blood sugar should be controlled < 10 mmol/L or 180 mg/dL. IV insulin infusion should be used with glucose as required.

• Keep a close watch on serum potassium concentration and supplement intake to maintain levels > 4.0 mmol/L.

Thrombo-prophylaxis

• All patients should receive an appropriate prophylactic dose of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), unless they have a coagulopathy/thrombocytopenia or are receiving therapeutic anticoagulation or heparin/epoprostenol as anticoagulation for renal replacement therapy.

• Patients with severe acute, chronic or acute on chronic renal impairment should have unfractionated heparin 5000 U SC 12-hourly, as LMWHs accumulate in renal failure.

• Once daily LMWH should be prescribed at 18:00 h, so that any necessary surgical procedures (e.g. removal of epidural catheters, tracheostomies, line insertions or removals) are not delayed the following day.

Analgesia and sedation

Guidelines

• The commonest indication for the initiation of analgesia/sedation is endotracheal intubation and ventilation. Some patients may tolerate this without any drugs but most will require analgesia and suppression of airway reflexes.

• Most ICUs employ continuous infusions of opiates and sedatives. The choice of agents depends on a number of factors, including drug pharmacokinetics, cost and personal preference (Tables 14.1a and b).

• Start with a small bolus dose prior to commencing an infusion. If this is insufficient to achieve the desired level of analgesia/sedation, repeat the small bolus prior to each increase in infusion rate. This is to allow steady state drug levels to be achieved more quickly and reduces total cumulative dosage.

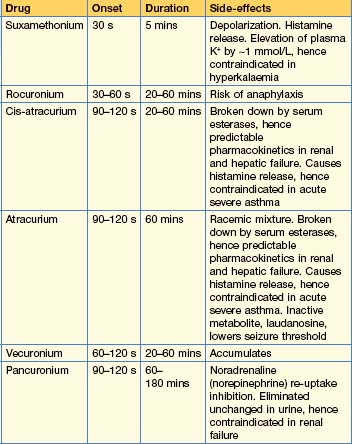

• Neuromuscular blockade (Table 14.2) should only be used in patients when sedation/analgesia does not achieve the defined goals: most commonly, failure to achieve adequate ventilation or as part of a cooling protocol. Intermittent bolus dosing is usually preferable to IV infusions. If given by infusion, daily cessation is mandatory. Prolonged use of neuromuscular blocking agents is associated with a higher incidence of critical illness neuromyopathy.

• Sedative drugs do not achieve physiological sleep (as assessed by EEG); sleep deprivation is probably one of the principal causes of ICU delirium.

• Prolonged use of sedation/analgesia drugs is associated with a degree of neurochemical dependence/withdrawal syndromes. Weaning from prolonged use may require staged reduction over a period of days.

• Over-sedation is associated with a higher incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia, prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation, colonization with multiply resistant organisms, an increased requirement for neurological investigations, prolonged ICU stay and death.

Table 14.1a Continuous infusion sedative analgesic regimens

| Drug | Regime | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | Loading 5–15 mg Maintenance 1–12 mg/hour | Slow onset. Long-acting. Active metabolites. Accumulates in renal and hepatic impairment |

| Fentanyl | Loading 25–100 mcg Maintenance 25–250 mcg/hour | Rapid onset. Modest duration of action. No active metabolites. Renally excreted |

| Alfentanil | Loading 15–50 mcg/kg Maintenance 30–85 mcg/kg/hour (1–6 mg/hour) | Rapid onset. Relatively short-acting. Accumulates in hepatic failure |

| Remifentanil | Maintenance 6–12 mcg/kg/hour | Rapid onset and offset of action, with minimal if any accumulation of the weakly active metabolite. Significant incidence of problematic bradycardia. Expensive |

| Clonidine | Maintenance 1–4 mcg/kg/hour | An α2 agonist. Has marked sedative and atypical analgesic effects |

| Ketamine | Analgesia Induction 0.2 mg/kg/hour Maintenance 0.5–2.0 mg/kg 1–2 mg/kg/hour | Atypical analgesic with hypnotic effects at higher doses. Sympathomimetic; associated with emergence phenomena when given at hypnotic doses when usually co-administered with a benzodiazepine. Contraindicated in raised intracranial pressure |

Table 14.1b Continuous infusion sedative regimens

| Drug | Regime | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Propofol 1% | Loading 1.5–2.5 mg/kg Maintenance 0.5–4 mg/kg/hour (0–200 mg/hour) | IV anaesthetic agent. Causes vasodilatation and hence hypotension. Extrahepatic metabolism, thus does not accumulate in hepatic failure. Has no analgesic properties |

| Midazolam | Loading 30–300 mcg/kg Maintenance 30–200 mcg/kg/hour (0–14 mg/hour) | Short-acting benzodiazepine. Used with morphine. Active metabolites accumulate in all patients, esp in renal failure |

Respiratory failure

• Arterial oxygen tension is principally determined by the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), ventilation/perfusion matching and the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood (essentially Hb concentration).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree