, Arthur H. Cohen2, Robert B. Colvin3, J. Charles Jennette4 and Charles E. Alpers5

(1)

Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

(2)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

(3)

Department of Pathology Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(4)

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

(5)

Department of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

Abstract

Crescentic glomerulonephritis is not a specific disease but rather is a manifestation of severe glomerular injury that can be caused by many different etiologies and pathogenic mechanisms. The major immunopathologic categories of crescentic glomerulonephritis are immune complex-mediated, anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibody-mediated, and pauci-immune, which usually is antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-mediated [1]. Table 9.1 shows the relative frequency of these immunopathologic categories of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Crescentic glomerulonephritis can occur as a renal-limited process or as a component of systemic small-vessel vasculitis, such as IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura), cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, Goodpasture’s syndrome, or ANCA vasculitis [2–5]. In addition to small-vessel vasculitis, the kidneys also are a frequent site of involvement by other forms of vasculitis, such as polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease, giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis [3, 5] (Table 9.2).

Introduction/Clinical Setting

Crescentic glomerulonephritis is not a specific disease but rather is a manifestation of severe glomerular injury that can be caused by many different etiologies and pathogenic mechanisms. The major immunopathologic categories of crescentic glomerulonephritis are immune complex-mediated, anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibody-mediated, and pauci-immune, which usually is antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-mediated [1]. Table 9.1 shows the relative frequency of these immunopathologic categories of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Crescentic glomerulonephritis can occur as a renal-limited process or as a component of systemic small-vessel vasculitis, such as IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura), cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, Goodpasture’s syndrome, or ANCA vasculitis [2–5]. In addition to small-vessel vasculitis, the kidneys also are a frequent site of involvement by other forms of vasculitis, such as polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease, giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis [3, 5] (Table 9.2).

Table 9.1

Frequency of immunopathologic categories of crescentic glomerulonephritis in over 3,000 consecutive native kidney biopsies evaluated by immunofluorescence microscopy in the University of North Carolina Nephropathology Laboratory

Any crescents (n = 487) | >50 % crescents (n = 195) | Arteritis in biopsy (n = 37) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Immunohistology | |||

Pauci-immune (<2 + Ig) | 47 % (227/487) | 61 % (118/195)a | 84 % (31/37) |

Immune complex (>2 + Ig) | 49 % (238/487) | 29 % (56/195) | 14 % (5/37)b |

Anti-GBM | 5 % (25/487)c | 11 % (21/195) | 3 % (1/37)d |

Table 9.2

Names and definitions of vasculitis adopted by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the nomenclature of systemic vasculitis (partial modified listing)

Large-vessel vasculitis | Vasculitis affecting large arteries more often than other vasculitides. Large arteries are the aorta and its major branches. Any size artery may be affected |

Takayasu arteritis | Arteritis, often granulomatous, predominantly affecting the aorta and/or its major branches. Onset usually in patients younger than 50 |

Giant cell arteritis | Arteritis, often granulomatous, usually affecting the aorta and/or its major branches, with a predilection for the branches of the carotid and vertebral arteries. Often involves the temporal artery. Onset usually in patients older than 50 and often associated with polymyalgia rheumatica |

Medium-vessel vasculitis | Vasculitis predominantly affecting medium arteries defined as the main visceral arteries and their branches. Any size artery may be affected. Inflammatory aneurysms and stenoses are common |

Polyarteritis nodosa | Necrotizing arteritis of medium or small arteries without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in arterioles, capillaries, or venules and not associated with ANCA |

Kawasaki disease | Arteritis associated with the mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome and predominantly affecting medium and small arteries. Coronary arteries are often involved. Aorta and large arteries may be involved. Usually occurs in infants and young children |

Small-vessel vasculitis | Vasculitis predominantly affecting small vessels, defined as small intraparenchymal arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and venules. Medium arteries and veins may be affected |

ANCA-associated vasculitis | Necrotizing vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries), associated with MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA. Not all patients have ANCA. Add a prefix indicating ANCA reactivity, e.g., PR3-ANCA, MPO-ANCA, ANCA-negative |

Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) | Necrotizing vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Necrotizing arteritis involving small and medium arteries may be present. Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is very common. Pulmonary capillaritis often occurs. Granulomatous inflammation is absent |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) (GPA) | Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis affecting predominantly small to medium vessels (e.g., capillaries, venules, arterioles, arteries, and veins). Necrotizing glomerulonephritis is common |

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg- Strauss) (EGPA) | Eosinophil-rich and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory tract, and necrotizing vasculitis predominantly affecting small to medium vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia. ANCA is more frequent when glomerulonephritis is present |

Immune complex vasculitis | Vasculitis with moderate to marked vessel wall deposits of immunoglobulin and/or complement components predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, arterioles, and small arteries). Glomerulonephritis is frequent |

Anti-GBM disease | Vasculitis affecting glomerular capillaries, pulmonary capillaries, or both, with basement membrane deposition of anti-basement membrane autoantibodies. Lung involvement causes pulmonary hemorrhage, and renal involvement causes glomerulonephritis with necrosis and crescents |

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV) | Vasculitis with cryoglobulin immune deposits affecting small vessels (predominantly capillaries, venules, or arterioles) and associated with cryoglobulins in serum. Skin, glomeruli, and peripheral nerves are often involved |

IgA vasculitis (IgAV) (Henoch-Schönlein) | Vasculitis, with IgA1-dominant immune deposits, affecting small vessels (predominantly capillaries, venules, or arterioles). Often involves skin and gut and frequently causes arthritis. Glomerulonephritis indistinguishable from IgA nephropathy may occur |

Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (Anti-C1q vasculitis) | Vasculitis accompanied by urticaria and hypocomplementemia affecting small vessels (i.e., capillaries, venules, or arterioles) and associated with anti-C1q antibodies. Glomerulonephritis, arthritis, obstructive pulmonary disease, and ocular inflammation are common |

Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrane Disease

Anti-GBM disease is a small-vessel vasculitis that affects the glomerular capillaries and pulmonary alveolar capillaries [6, 7]. It may occur as an isolated glomerulonephritis or as the renal component of a pulmonary-renal syndrome. In the latter instance, the term Goodpasture’s syndrome is appropriate.

Pathologic Findings

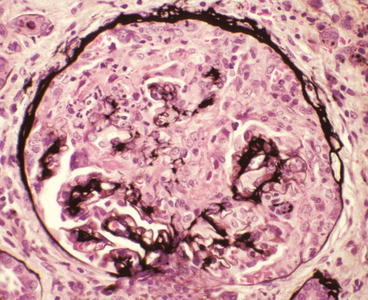

Light Microscopy

By light microscopy, the acute glomerular lesion is characterized by segmental to global fibrinoid necrosis with crescent formation in over 90 % of patients [1]. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and silver stains demonstrate breaks in the GBM in areas of necrosis (Fig. 9.1). Glomerular segments that do not have necrosis often are remarkably normal or have a slight increase in neutrophils. Marked neutrophil infiltration is observed in association with the necrosis in occasional specimens. Features of aggressive immune complex glomerulonephritis are notably absent, such as marked capillary wall thickening and endocapillary hypercellularity. Often there are breaks in Bowman’s capsule, occasionally with associated reactive multinucleated giant cells.

Fig. 9.1

Glomerulus from a patient with anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease showing a very large cellular crescent and extensive destruction of approximately 80 % of the tuft. A few silver-positive intact profiles of GBM are present at the hilum (Jones silver stain)

With time, foci of glomerular necrosis evolve into glomerular sclerosis, and cellular crescents become fibrous crescents. Acute tubulointerstitial inflammation that is centered on necrotic glomeruli evolves to more regional or generalized interstitial fibrosis with chronic inflammation and tubular atrophy.

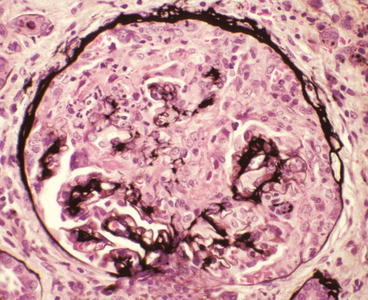

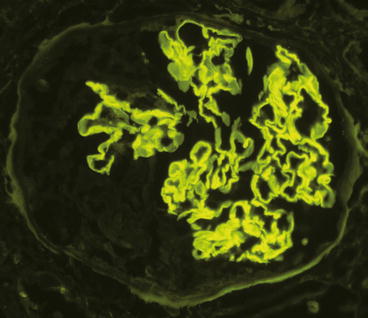

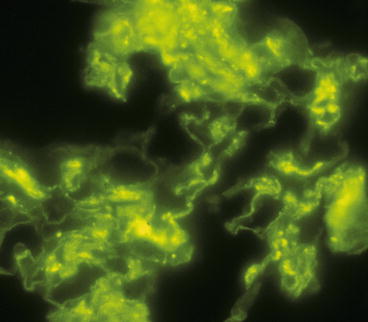

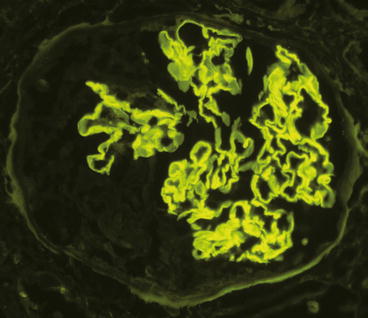

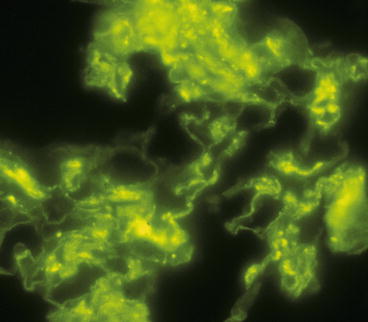

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Immunohistology demonstrates intense linear staining of the GBM (Fig. 9.2), predominantly for immunoglobulin G (IgG) along with more granular and discontinuous staining for C3 (Fig. 9.3). Immunoglobulin A (IgA)-dominant anti-GBM disease is very rare [8]. Irregular staining for fibrin occurs at sites of fibrinoid necrosis and within crescents. In some specimens, the fibrinoid of glomeruli is so extensive that identification of linear staining along intact segments of GBM is difficult. Care must be taken not to misinterpret anti-GBM disease with extensive destruction of GBMs as pauci-immune disease.

Fig. 9.2

Glomerulus from a patient with anti-GBM disease showing linear staining of the GBM by direct immunofluorescence microscopy using an antibody specific for immunoglobulin G (IgG)

Fig. 9.3

Glomerulus from a patient with anti-GBM disease showing irregular granular staining of the capillary walls by direct immunofluorescence microscopy using an antibody specific for C3

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy reveals no immune complex-type electron-dense deposits unless there is concurrent immune complex glomerulonephritis. Glomerular basement membrane gaps are present in areas of necrosis and crescent formation. Cellular crescents typically contain electron-dense fibrin tactoid strands.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Anti-GBM disease is caused by autoantibodies directed against the α3 chain in the noncollagenous domain of type IV collagen [9]. Serologic confirmation of anti-GBM disease should be sought, but approximately 10–15 % of patients with anti-GBM disease have negative results. About a quarter to a third of patients with anti-GBM disease also have ANCA [10]. Thus, all anti-GBM patients should be tested for ANCA. Patients with both anti-GBM and ANCA have an intermediate prognosis that is worse than ANCA alone but better than anti-GBM alone. Anti-GBM antibodies characteristically occur as one episode that clears with immunosuppressive therapy, whereas ANCA disease is characterized by more persistent antibodies and frequent recurrence of disease. Patients with combined disease may have permanent remission of the anti-GBM disease with recurrence of the ANCA disease alone.

Approximately half the patients with anti-GBM disease present with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis without pulmonary hemorrhage, and the other half have pulmonary-renal syndrome (Goodpasture’s syndrome). However, most patients with pulmonary-renal syndrome have ANCA disease rather than anti-GBM disease [11].

Anti-GBM is the most aggressive form of crescentic glomerulonephritis and has the worst prognosis, especially if aggressive immunosuppressive treatment is not instituted quickly before the serum creatinine is >6 mg/dL [1, 7, 12]. The serum creatinine at the time treatment is begun is a better predictor of outcome than any pathologic feature. The current approach to treatment uses high-dose cytotoxic agents combined with plasma exchange [6, 7, 12].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree