![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the pharmacy student, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Discuss the role of patient counseling techniques such as the three prime questions and behavioral change models.

2. Recognize pharmacist-centered, patient-centered, and environmental barriers to change and how to overcome them.

3. Explain how motivational interviewing is useful and effective as a style of counseling.

4. Discuss the role of the five core communication principles as they apply to motivational interviewing.

5. Assess a patient’s readiness and self-efficacy to change their behaviors.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Whether in a community or clinical setting, pharmacists usually do not have abundant time to fully discuss medication and behavior change issues with patients. In the case of many community settings, the environment and other factors may serve as barriers; however, evidence-based communication strategies are crucial to resolving barriers, to increasing patient adherence to medications, and to improving clinical outcomes. Even in environments conducive to optimal counseling and effective medication therapy management (MTM), the most effective medications can be rendered ineffective if patients struggle to make behavior changes in medication adherence and other disease management behaviors. Motivational interviewing (MI) has been shown to be an effective counseling method for ambivalent or resistant patients, as it is designed to resolve ambivalence and to help patients decide internally and on their own to make changes.

THE OMNIBUS RECONCILIATION ACT OF 1990 AND THE INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE MODEL

THE OMNIBUS RECONCILIATION ACT OF 1990 AND THE INDIAN HEALTH SERVICE MODEL

Patient counseling standards originally were set in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA 1990), which is a law mandating that pharmacists offer counseling to patients regarding their prescriptions.1If the patient accepts this offer, pharmacists should discuss the following:

![]() Name of medication

Name of medication

![]() Intended use and expected action

Intended use and expected action

![]() Route, dosage form, dosage, and administration schedule

Route, dosage form, dosage, and administration schedule

![]() Proper storage

Proper storage

![]() Common adverse effects that may be encountered

Common adverse effects that may be encountered

![]() Techniques for self-monitoring of drug therapy

Techniques for self-monitoring of drug therapy

![]() Prescription refill information

Prescription refill information

![]() Action to take if a dose is missed

Action to take if a dose is missed

![]() Potential drug—drug or drug—food interactions or other therapeutic contraindications

Potential drug—drug or drug—food interactions or other therapeutic contraindications

Although the law was intended for Medicaid patients, individual states adopted rules to make counseling applicable to other patients, as well.1 Thus, counseling is one of the tools that may be used to provide MTM services. One of the limitations of counseling, however, is that information generally is provided in a one-way, provider-centered manner (i.e., pharmacist to patient or pharmacist to caregiver). Instead, the pharmacist should ask questions to elicit needed information from the patient to fill the medication(s) in question and also to ensure that all of the patient’s medications are providing optimal benefit. This can become a time-consuming process.

To streamline the process for discussing medications, the “three prime questions” of the Indian Health Service Model can help determine the patient’s baseline understanding of a medication.2 This method promotes a conversation with the patient during which the pharmacist elicits information that the patient already knows, with the intention to fill in any gaps of understanding. Thus, discussing medications does not consist of simply the pharmacist reciting everything about the medication. This is a time-efficient method of conversing with the patient and consists of asking the following prime questions:

1. What did your prescriber tell you this medication is for?

2. How did your prescriber tell you to take the medication?

3. What did your prescriber tell you to expect?

These questions stimulate a discussion ofpurpose for the medication, directions for use, all aspects of dosing and administering, and what the desired outcome should be. The questions are asked in a nonthreatening, non-judgmental manner to encourage the patient to seek more information for optimal medication use. The pharmacist should ask subsequent questions to provide information that will help the patient achieve his/her goals.2 Subsequent questions for each may include:

![]() What problem or symptoms is this medication supposed to help? What is the medication supposed to do? (Prime question #1)

What problem or symptoms is this medication supposed to help? What is the medication supposed to do? (Prime question #1)

![]() How often and how long are you supposed to take it? How much are you supposed to take? What do the directions (e.g., two times a day) mean to you? (Prime question #2)

How often and how long are you supposed to take it? How much are you supposed to take? What do the directions (e.g., two times a day) mean to you? (Prime question #2)

![]() What good and bad effects did your physician tell you to watch out for? How will you know if the medication is working? What are you supposed to do if it doesn’t work? (Prime question #3)

What good and bad effects did your physician tell you to watch out for? How will you know if the medication is working? What are you supposed to do if it doesn’t work? (Prime question #3)

DISCUSSING BEHAVIOR CHANGES WITH PATIENTS

DISCUSSING BEHAVIOR CHANGES WITH PATIENTS

The pharmacist may find that the patient requires change(s) in therapy, including a need to alter doses or to initiate or consolidate medications. However, many pharmacists discover when initiating conversations that the underlying problems often consist of patients not engaging in healthy behaviors (e.g., nonadherence to medications, not eating healthy, or not exercising regularly). Patients also engage in harmful behaviors/habits (e.g., smoking, drinking excessive alcohol, and others). Although medications and doses may be optimized for the patient’s particular disease or condition, the aforementioned unhealthy behaviors can prevent goal achievement (e.g., for diabetes: HbA1C (A1C) <7%, blood pressure <140/80 mm Hg, and LDL <100 mg/dL). Moreover, maintaining healthy eating habits and regular physical activity comprise the cornerstone of therapy for many chronic diseases, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. In many cases, the patient lacks the motivation needed to change these underlying behaviors that would optimize outcomes.3

The Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change

A well-studied model that can be used to explain or predict behavior change is the Transtheoretical Model (TTM).4 This model does not explain behavior change as a single event in time; rather, it takes into account that change is a process for many patients that occurs over time. It includes five stages of motivational readiness for change, which concerns emotional, cognitive, and behavioral readiness.4 A wide variety of target health behaviors have been studied using the TTM paradigm, including smoking cessation, weight control, exercise, stress management, alcohol and drug abuse, screening recommendations adherence, and medication management.5 Patients cycle through the stages of change before being able to maintain long-term change, and the temporal association can be long or short. In other words, patients could be in one stage for years, or they could move rapidly through several stages in a matter of days or sometimes even hours—perhaps even during the course of a formal counseling session. Relapse is sometimes considered a stage in relation to the TTM concepts since it is common; in smoking cessation, for example, the average number of relapse episodes before a successful quit has been four to five. Upon relapse, patients may revert back several stages in the TTM readiness continuum as a result of the feelings of failure that a relapse can bring.

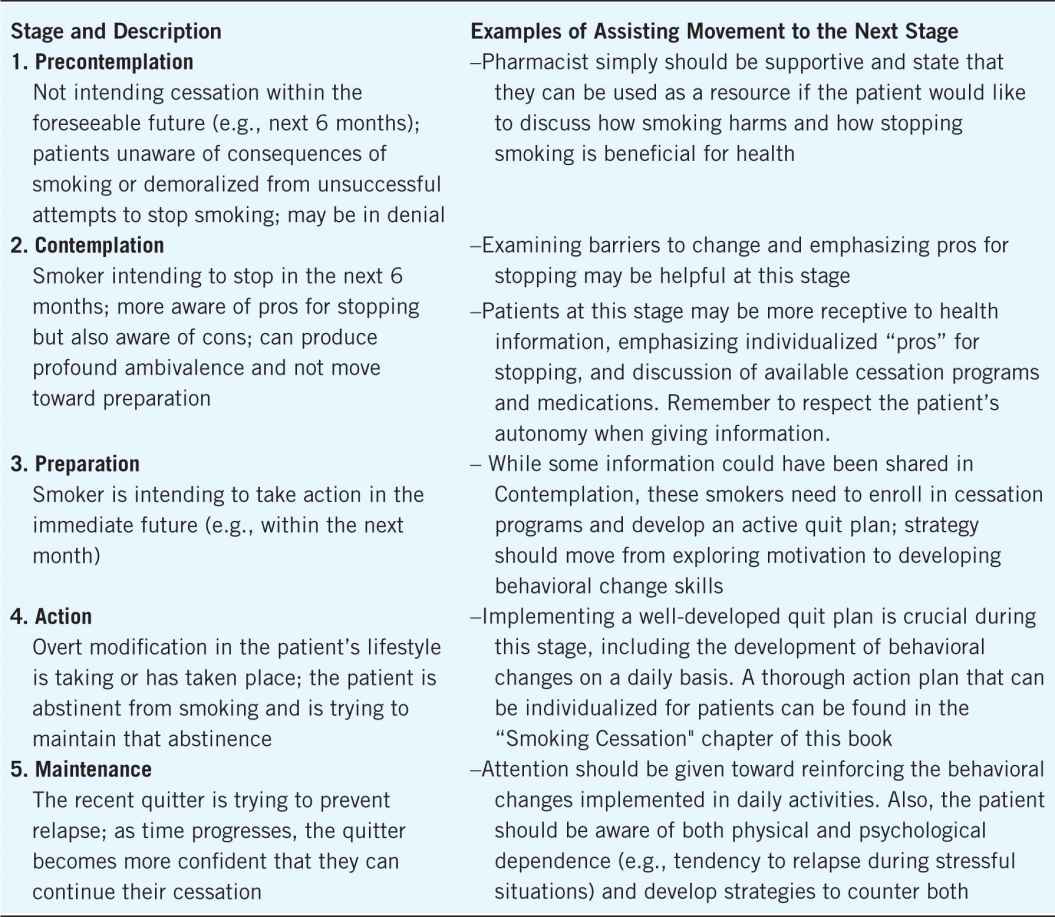

The utility of the TTM for the pharmacist is to recognize the stage of behavioral change the patient is currently in, and then use the associated stage-matched tools to help the patient move toward the next stage. Table 3–1 describes the five primary stages of change, including precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.4 After classifying a patient in one of these stages, pharmacists can develop appropriate interventions to assist the patient in moving toward the next stage. A patient often has ambivalence because the “cons” for moving toward the next stage outweigh the “pros.” For example, perhaps the smoker discussing the need to set a quit date cannot commit to this because the person “enjoys smoking,” has a spouse who is also a smoker, has enough money to buy two packs per day, and has not yet experienced an adverse health problem because of this “habit.” Perhaps the patient is aware of diseases and problems that could result from continuing to smoke and is intending a quit attempt within the next 6 months (contemplation stage). The problem may be that the listed “pros” for continuing to smoke outweigh the listed “cons” for quitting, such as the expense of smoking cessation medications, history of nicotine patches “not working”, an adversity to experiencing intense cravings, and “missing” the daily routine of smoking. In this case, strategies would include interviewing in a way that the patient ends up countering self-identified barriers in an individualized way that should assist the patient in moving toward the preparation and action stages.

Table 3–1. Five Stages of the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change as Applied to Smoking Cessation

The Readiness Ruler

The willingness for patients to change their behavior in a meaningful and long-lasting way is highly individualized. Using a “readiness ruler” is another tool for discussing change in a positive manner.6 The readiness ruler asks the patient to rate his/her level of readiness to change on a scale of 0 to 10, where “0” represents “absolutely not ready” and “10” represents “absolutely ready.” Even if the patient scores himself or herself with a low number, such as a “4,” the pharmacist should focus on the positive aspect by comparing the stated 4 with the minimum, saying, “why a 4 and not a 1?” Then, to infer an expectation for only incremental change for the patient, the pharmacist could say, “What would need to happen for you to choose a score of 5 or 6?” The pharmacist should not suggest a “10” because that suggests too much of a change all at once and also may shame the patient who may then perceive that the 10 he or she is “failing” to achieve is expected. This can create more resistance for the patient and can interfere with building a therapeutic, trusting relationship between patient and pharmacist.

BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION

BARRIERS TO COMMUNICATION

As opposed to traditional counseling, MI involves developing a partnership with a patient in order to exchange information and facilitate a shared, informed decision.3 MI will be discussed as a framework for addressing barriers; thus, it is important to first note barriers to communication that may exist within the current pharmacist–patient relationship. Barriers to communication can be personal (or pharmacist-centered), patient-centered, and environmental.7

Personal (Pharmacist-Centered) Barriers

Some pharmacists think that good counseling skills are innate and that certain people are born with these skills. This is rarely true. Effective counseling skills, especially using MI, can be learned and developed if the pharmacist is willing. Consider that a significant component for entrance into most schools of pharmacy involves an interview. The interview is designed to target as potential pharmacists those who have adequate baseline communication skills. Although most pharmacists should have good baseline skills, confidence may be lacking that he or she can communicate at the level necessary to provide MTM and develop services.7

Pharmacists may not be aware that several factors, including poor body positioning, could lead a patient to feel that the pharmacist is not being attentive. The pharmacist should try to stay within 1&1/2 to 4 feet from the patient who is being counseled—not too close to invade “personal space,” and not too far away either. Distracting body movements should also be avoided, such as folding arms across the chest, tapping a foot, clicking a pen, or “playing” with one’s hair, for example. In general, any movement that could be construed by the patient as not having the pharmacist’s full attention should be avoided. A very common position that pharmacists take is facing their computer terminal instead of the patient. Although this is conducive to using the computer to gather important information, the patient could perceive this as the pharmacist not being attentive.

Remember that nonverbal communication is as important as verbal. When counseling the patient, lean squarely toward the patient, maintain an open body posture and a reasonable amount of eye contact (50–75% of interaction time), and control any distracting mannerisms. If nonverbal communication is incongruent with what the pharmacist is saying, the patient is most likely to believe the nonverbal communication. The pharmacist always should use nonverbal behaviors that are nonjudgmental and nonthreatening. Maintaining good eye contact, using responsive body language (e.g., head nodding), and using a calm and conversational tone will go a long way in communicating a spirit of collaboration.

Regarding one’s voice, the pharmacist should be vigilant and sensitive to tone, particularly in regard to a tone the patient may perceive as antagonistic, judgmental, or condescension. The result could be resentment and resistance to change, thus increasing barriers to good communication, and ultimately not being effective in an MTM encounter. An overarching point to remember is to be vigilant of how the message is being perceived by the patient and act accordingly.

Other personal barriers are less obvious. The pharmacist should monitor for internal conversations or judgments that could create barriers. For example, a pharmacist filling prescriptions in the back of the pharmacy may overhear a patient checking out and giving the pharmacy technician a difficult time over the price of a medication. The pharmacist may not “jump in” right away in order to think about how to deal with this particular situation. This is fine, of course, and prevents a rash action by the pharmacist. However, when in conversation with a patient, if that pharmacist’s thoughts are wandering—or perhaps thinking about all of the tasks that must be completed after that conversation—those thoughts (i.e., internal conversations) are now overriding the ability to listen effectively.

Finally, one might want to be aware of using a “Righting Reflex” when discussing behavioral change with patients.3 This comes into play when the pharmacist assumes the position of expert on medication and changing behaviors while not taking the patient’s goals into account. The righting reflex will be discussed in more detail in the MI sections.

Patient-Centered Barriers

Barriers that are patient-centered are sometimes easy to detect but difficult to overcome.7 Patients could have language barriers for which the pharmacist would need to use an interpreter. Specialized educational tools or other accommodations might have to be used for patients with visual, hearing, or physical challenges. For example, older patients may have trouble discerning higher-pitched voices, so communication may require using a lower pitch. Low literacy of the written or spoken word, as well as low health literacy may, be common in many locations, and can inhibit effective communication.7 For example, written instructions should be composed at the fourth to sixth grade reading level for patients, and the pharmacist should use plain language rather than medical terminology. Verbal instructions should be direct, succinct, unambiguous, and followed-up to check for patient understanding.

Finally, a patient may not be reacting to the present experience in the pharmacy, but to past experiences. A bad experience with another pharmacist or staff person, or other health-care encounters, may have left emotions of fear and anger toward providers in general or pharmacists specifically. It is important to consider all of the cues, both verbal and nonverbal, that the patient is giving to try to understand the overall problem. MI is a method with tools for attempting to assess all cues together and responding in a patient-centered manner.

Environmental Barriers

This final barrier is the most obvious but is still very significant and difficult for many pharmacists to overcome. The prescription counter is positive from several standpoints: patients needing a prescription filled can identify this area quickly, it provides a private and secure area for pharmacy staff, and staff easily can watch over the prescription area from this vantage point. However, the prescription counter can be intimidating for patients. They may not be able to readily identify the pharmacist, and they may have the impression that the pharmacist is not accessible.7 The process of dropping off prescriptions and picking them up in certain areas may not be well identified and can be confusing. Most pharmacies have a “patient counseling area,” but the area should be reappraised on a regular basis for its ability to meet a variety of patient counseling needs. Many designated patient counseling areas have a lack of privacy due to space limitations. There are also other factors to examine regarding the designated patient counseling area. Is it accessible for the patient? Do pharmacy personnel immediately approach the patient when standing at the counseling area? Is the area itself blocked or cluttered by advertisements or displays? Does the patient have to “look up” to converse with pharmacy personnel? These considerations must be appraised and rectified, perhaps even reevaluating workflow issues, for effective counseling sessions to occur.

A good workflow system with attention to the patient could minimize environmental barriers. As the patient approaches the prescription area, the patient should be able to attain the pharmacist’s attention quickly. Also, prescription areas are noisy and crowded, with plenty of chances to be interrupted by phone calls and questions from technicians and other patients. The pharmacist should train technicians how to triage calls well and not interrupt a counseling session unless it is absolutely necessary. Consider reorganizing the workflow, if necessary, to shift dispensing tasks more to the technicians and using support personnel. Making the pharmacy conducive for providing MTM services is an individualized process for every location. The pharmacist should be willing to make changes that will be more conducive to providing effective counseling – including privacy concerns. Finally, it is important to ensure that the flow is reasonable from the patient’s perspective. The process for leaving prescriptions, picking up medications, and especially how to receive counseling should be unambiguous for the patient.

Non-pharmaceutical items could create confusion in the communication process about healthy behaviors. For MTM to be successful, patients should view the pharmacy as a place where health-care is deemed important. If the pharmacy sells alcohol or cigarettes, patients could perceive these items as being counterproductive to health. This could create an unintentional barrier to discussions about health behavior change regarding habits associated with these products. Also, tobacco cessation products should be in an area convenient and conducive for initiating therapeutic conversations. In addition, placement of herbals and vitamins is important. While the average person may understand the usefulness of a multivitamin, placing scientifically unproven products together in the same area as legitimate vitamins and herbals could lead the patient to assume all products in that area are useful; this could get in the way of an effective, trusted conversation about needed supplements (e.g., calcium for the patient with osteoporosis, versus unproven “remedies” that offer unfounded hope for cure or symptom relief).

While it is not absolutely essential for a pharmacy to have a private room dedicated for counseling, having one available would greatly decrease the environmental barriers.7 A private consultation room is indeed the ideal environment for MTM sessions and is becoming more common in community pharmacy settings. Studies have shown that patients counseled in a private area in the pharmacy were more adherent with their medication regimens, retained more information, and were more satisfied with their care. A dedicated room could be stocked with equipment and education materials needed to provide MTM services (as discussed in the disease state management chapters), and patient files could be kept in a locked cabinet for easy reference. The pharmacist could schedule sessions to occur at specific times convenient for both patient and pharmacist rather than simply waiting for a spontaneous encounter when the patient comes to pick up monthly prescriptions.

The most important barrier for pharmacists who want to initiate MTM services is overcoming patient expectations regarding pharmacy flow. Based on their past experiences, patients have come to expect a certain flow to the services provided by their pharmacist. However, patients experiencing MTM services are more likely to expect these services in the future, particularly if barriers to receiving such services are minimized.

WHY THE NEED FOR MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING?

WHY THE NEED FOR MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING?

Traditional pharmacist-centered counseling sessions have centered on giving information to the patient and advising on medications and diseases. Medication issues such as adverse effects, proper medication administration, and identification of efficacy are paramount points for patients to understand. Because of time constraints, pharmacists may ask directed questions to discern a patient’s baseline knowledge and then give specific information to “fill the gaps.” However, many patients have diseases where behavior changes like medication adherence and lifestyle change are critical to achieving optimal outcomes (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia). Thus, increasing the patient knowledge regarding medications and diseases is a critical component to achieving optimal outcomes. However, knowledge alone is not the answer.8

MI is an effective communication strategy set that is designed to assess a patient’s readiness to change, and

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree