Cough

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

A cough is a natural protective process. Normal, healthy school-aged children experience 10 to 12 coughing episodes per day. Coughing has two main functions: (1) clearing the larynx, trachea, and bronchi of inhaled material, mucous, infectious agents, noxious substances, foreign particles, edema fluid, and pus and (2) increasing oxygenation in the blood via post-cough inspiration and breathing. These mechanisms are thought to partially contribute to the cough of exercise-induced asthma and the early morning cough typical of asthma.

Mechanical and chemical cough receptors are located primarily in the epithelium of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, but are also found in the esophagus, diaphragm, stomach, and pericardium. When irritated, they initiate a reflex arc via the vagus nerve to the cough center in the medulla, which then causes a reflex arc via the vagus, phrenic and spinal motor nerves to initiate a four-step process. First, there is an inspiratory phase, followed by a forced expiratory phase against a closed glottis to build up intrathoracic pressure. Second, the glottis opens with rapid expiration and causes the cough sound, followed by a deep inspiration. Prolonged or violent coughing can cause vomiting, fractured ribs, muscle spasm, urinary incontinence, and syncope.

• ETIOLOGY

The causes of a cough are numerous and can be due to disorders of the upper respiratory, lower respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular systems. Viral upper respiratory infections, allergic rhinitis, and bacterial sinusitis all produce cough as an associated symptom, probably due to post-nasal drip of mucoid or purulent material. The lower respiratory tract is the primary source of cough as a symptom. Infections can be caused by viruses (acute bronchitis, viral pneumonia, and influenza), bacteria (pneumonia, tuberculosis, and whooping cough), or fungi (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and candida). Inflammatory conditions of the lungs leading to cough include asthma, COPD, and smoking. Drug-induced pulmonary adverse effects also have cough as a major symptom complex. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an important gastrointestinal cause of cough. Various malignancies involving the respiratory tract may also present with a cough as the primary symptom. Finally, congestive heart failure is the most common cause of cough due to disorders of the cardiovascular system.

• DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of the cause of a cough is complex and requires a careful history, physical examination, and laboratory studies. The cough history and timing of the cough can provide important diagnostic clues. A good example of this is patients with a nighttime cough. Coughs due to GERD and upper airway cough syndrome (aka post-nasal drip) usually occur shortly after lying down. Coughs caused by congestive heart failure typically occur 2 to 3 hours after lying down, whereas coughs due to asthma typically occur from 2 to 6 o’clock in the morning.

There are several ways of classifying coughs to facilitate diagnosis. Coughs are called acute if the duration is less than 3 weeks and chronic if the duration is greater than 3 weeks. They can also be classified based on amount of mucous brought up during coughing. Coughs that present with copious mucous are called productive or wet coughs and those with scant or no mucous production are called dry coughs. However, neither of these classification systems is absolute. Some have used the term subacute cough to describe a cough lasting 3 to 8 weeks, with chronic coughs defined as lasting more than 8 weeks. Similarly, there are some conditions that while usually presenting with a dry cough, but can generate a productive cough under specific circumstances such as time of day and severity of illness. These are called mixed coughs.

• ACUTE COUGH WITH PRODUCTIVE SPUTUM

The three main causes of an acute productive cough are bacterial pneumonia, acute bronchitis, and acute exacerbation of COPD (Table 8.1).

| TABLE 8.1 | Productive Cough |

Bacterial Pneumonia

Typically, community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CAP) presents with a previous history of upper or lower respiratory infection that has transformed into a purulent productive cough throughout the day (mucous is opaque, dark yellow, brownish, or may be blood tinged). Typical objective findings include; fever >100°F (37.8°C), crackles upon auscultation of lung fields, tachypnea (normal is 12 to 20 breaths per minute), tachycardia (>100 beats/min), a chest x-ray with a consolidated infiltrate, and a white blood cell count greater than 10,000 cells per microliter, with >80% mature (polys, segs, PMNs), plus immature neutrophils (bands, stabs). Patients with more widespread disease may present with an inability or difficulty speaking in complete sentences or use ancillary muscles of the neck (sternocleidomastoids) to augment inspiration due to inadequate oxygen intake. For larger consolidated infiltrates, dullness on percussion, absent breath sounds, and the presence of bronchophony, egophony, or whispered pectoriloquy will correspond with the location of the infiltrate on the chest x-ray. Unfortunately, there is no individual or set of signs and symptoms that have a sensitivity and specificity greater than 65%, and because of the Medicare standard for starting antibiotics within 6 hours of admission for patients with potential CAP, the diagnosis ends up being primarily a clinical diagnosis. Therefore, in many cases empiric antibiotic therapy is started before the diagnosis is confirmed.

There are many confounding variables that interfere with quickly arriving at the diagnosis. In the elderly, they may not mount a vigorous febrile response or may be taking medications such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen for osteoarthritis that may mask a febrile response due to their antipyretic effects. Many times the elderly present without cough as a prominent symptom. Sudden changes in behavior, attention, or consciousness (obtundation) may be the primary symptom of bacterial pneumonia in the elderly. Also in patients with impaired swallowing or cough reflex, aspiration of gastric contents or food can occur, causing a bacterial pneumonia (aspiration pneumonia). All geriatric patients with a change in behavior or cough should be checked for pneumonia or other infectious processes such as urinary tract infections.

Common causative agents in CAP are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. Hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia includes a wide range of bacterial pathogens typically gram-negative rods, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, or penicillinase-producing gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus. Other bacteria that cause about 25% of all community-acquired pneumonia are called atypical pneumonias or walking pneumonias. Their systemic symptoms tend to be milder; there is a lower incidence of productive cough and less of a febrile response compared to typical bacterial pneumonias. Similarly, patients with viral or atypical pneumonia do not mount as much of a neutrophilic response as seen with most bacterial pneumonias. Radiologically, viral and atypical infiltrates differ from bacterial findings because they tend to be interstitial rather than lobar in nature, yet can have great variability and overlap with bacterial pneumonia. While lung auscultation can reveal a range of findings from crackles to rhonchi, atypical and viral pneumonias have a much higher frequency of wheezing than bacterial infections. Also, viral and atypical pneumonias tend to have more extrapulmonary manifestations than bacterial infections. Recently, procalcitonin serum levels are being used to differentiate bacterial infections from atypical or viral infections. In bacterial pneumonias, serum procalcitonin levels are usually greater than 0.5 μg/L. Elevated procalcitonin levels usually are absent in viral and atypical infections. Because of the difficulty in many cases determining the etiology, standards for the treatment of CAP require coverage of common bacterial pathogens as well as common atypical pathogens.

Acute Bronchitis (“Chest Cold”)

Over 90% of the cases of acute bronchitis in teens and adults are viral and antibiotics offer no benefit in terms of reducing symptoms or shortening the course of disease. Many times these are part of the latter stages of a viral URI. Symptoms include a productive cough with mucoid sputum, which may be green tinged, low-grade fever if any, and a normal chest x-ray. Auscultation of the lungs is normal most of the time with occasional rhonchi that clear with coughing. Tachypnea and tachycardia are uncommon and when they occur, pneumonia should be suspected. The pathogens are generally the same as those for the common cold with more severe presentations: rhinovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, coronavirus, and adenovirus. Symptoms last from 1 to 3 weeks. Many patients with acute bronchitis develop bronchial hyperresponsiveness and may experience expiratory wheezes. For that reason, inhaled β-adrenergic bronchodilators such as albuterol are the treatment of choice.

• CHRONIC COUGH WITH SPUTUM PRODUCTION

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) involves permanent changes to lung structure primarily due to long-term smoking. It is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 21. Patients generally present with a productive cough due to excess mucous production. In the early stages, smoker’s cough, auscultation, and percussion of the lungs may be without findings. As the disease progresses auscultation reveals primarily rhonchi, but wheezing and occasional crackles may occur. In later stages known as emphysema, the alveoli lose their elasticity and air becomes trapped in peripheral lung fields. Auscultation of the lungs in patients with emphysema reveals faint or no breath sounds in certain areas due to decreased pulmonary function and the lack of air movement in areas of severe emphysema. Stable patients are usually afebrile, but due to poor pulmonary function have tachypnea and tachycardia. As pulmonary function deteriorates, patients are forced to use ancillary muscles in taking breaths. Many patients with COPD have enlarged sternocleidomastoid muscles that contract with each breath to try and force more air into their oxygen-starved lungs and body.

• SUBACUTE/CHRONIC COUGH WITH NO SPUTUM PRODUCTION

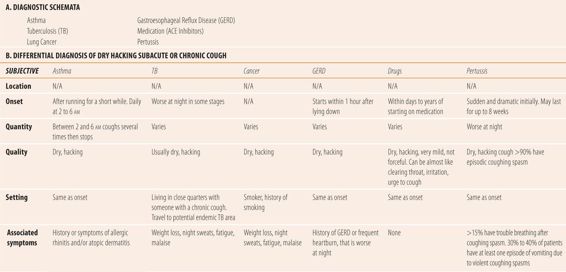

Asthma

Asthma is characterized by chronic inflammation of the small airways of the lungs, which leads to bronchospasm and the symptoms of asthma (see Table 8.2). Roughly 80% of asthmatics have involvement of IgE and up to 75% have a personal or family history of one or more of the atopic triad (allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, or asthma). Asthma attacks typically include a decreased peak expiratory flow rate due to bronchoconstriction, cough, expiratory wheezing, and difficulty breathing (dyspnea) that may be manifested by a tightness in the chest. In severe attacks, which may be called status asthmaticus if they do not respond quickly to standard treatments, tachypnea and tachycardia can occur and patients may feel like they are suffocating. Asthma may present with an acute attack, but frequently presents in a more subtle form as a cough. Because the vital capacity of the lungs is lowest between 2 and 6 in the morning, patients with subclinical bronchospasm become hypoxic and begin a series of coughs. These coughs serve to increase oxygen intake. Therefore, repeated coughing episodes between 2 and 6 AM can be an indicator of mild asthma and should be investigated. Additionally, people may get coughing spells while running or during exercise, causing them to stop exercising or playing due to the coughing. Sometimes the coughing is so subtle that patients may not associate it with breathing difficulties, so a careful history into the timing and setting of any dry cough is essential to ruling out asthma as a cause. Asthma and the pharmacist’s use of assessment skills in the management of patients with asthma are found in Chapter 21.

| TABLE 8.2 | Subacute/Chronic Nonproductive (Dry) Cough |

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The infection most commonly develops in the lungs, but extrapulmonary TB is not uncommon and can be found in the pleura, lymphatic system, kidney, central nervous system, and bone or joints. It is commonly transmitted by aerosolized droplets released into the air by coughing. When enough TB bacilli pass through the body’s protective barriers (respiratory tract mucosa, nasal hair, and cilia) and begin to grow in alveolar lung tissue, more than 90% of infected patient’s immune systems begin working to isolate the infection. Macrophages wall off the small number of TB bacillus forming a granuloma, and no further growth or clinical disease occurs. In more than 90% of patients, this primary infection is asymptomatic or patients think it is a “mild chest cold” as the body walls off the invading bacillus. Patients whose immune systems are functioning have no symptoms and normal chest x-rays. Six to eight weeks later, the only evidence of infection is a positive TB skin test. These walled off infections are called latent TB infections (LTBI). Because of this pathophysiology, more than 90% of the patients who eventually develop active TB do so because of a reactivation of a latent primary infection when the immune system fails to continue to hold the infection in check. The risk for developing active TB is highest within 2 years of the initial infection. In patients with LTBI, the chance of developing active TB can be drastically reduced by using daily isoniazid prophylaxis for 6 to 9 months, which kills off the remaining bacilli within a granuloma. In patients with a compromised immune system (AIDS, organ transplant recipients, and those on ≥ 15 mg prednisolone/day or TNF-α inhibitors), an immediate infection ensues usually in the form of an acute pneumonia called a primary progressive TB infection.

While there are many myths and fears regarding the transmission of TB from patients, the body’s mechanical defense systems remove most of the bacilli before they reach the alveoli. Generally, people who become infected have been exposed to large numbers of bacilli for a long period of time, meaning they have to live with someone with active TB in a poorly ventilated or closed environment. That is why TB is most common outside the United States and in indigent populations who live in closed cramped living conditions.

Active TB typically presents as a dry hacking cough. Patients have a history of travel to endemic areas, living with indigent families in foreign countries, or being around a person with a chronic cough for a prolonged period. Generally, auscultation and percussion of the lungs are normal and less than half the patients present with fever and/or night sweats. Fatigue, malaise, and weight loss can frequently accompany other symptoms. Patients with active TB generally have abnormal chest x-rays, and a positive TB skin test using PPD (tuberculin purified protein derivative), which is administered intradermally using the Mantoux technique. Generally, >15 mm induration (the lump, not the redness) is called a positive test. Greater than 10 mm or 5 mm are used depending on patients’ risk and immune status. Unfortunately, in many countries children are immunized with BCG vaccine (containing an attenuated form of bovine TB that is noninfectious), which confers partial immunity, but generally leaves patients with a lifelong positive PPD. For those patients, a new interferon-γ release assay such as QuantiFERON-TB Gold Test or T-Spot TB Test is much more specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and results are not altered by previous BCG vaccination as is the PPD.

Cancer

There are two main types of lung cancer. The first is small cell lung cancer (SCLC) previously called oat-cell lung cancer. The other main type is non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). More than 85% of all primary lung cancers are due to smoking. The risk of lung cancer increases directly with cumulative cigarette smoking exposure. Fortunately, even for long-term smokers, stopping smoking reduces the patient risk for subsequent lung cancer. Cancers that originate in other organ systems can metastasize to the lungs and cause symptoms mimicking primary lung cancer.

Patients with primary lung cancer present with a subacute or chronic dry hacking cough. Patients with COPD or a productive smoker’s cough might note a change in cough frequency or severity or notice blood in their sputum. Patients generally have a significant history of smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke. Most patients without COPD present with normal findings on auscultation and percussion of the lungs. Fever is rare. Patients may present with fatigue, malaise, unexplained weight loss, or some change in their ability to breathe normally. Patients suspected of having lung cancer need a referral for a chest x-ray or computerized tomography of the lungs. Definitive diagnosis of cancer type requires invasive procedures such as lung biopsy to obtain a specimen from the tumor or lesion.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Reflux disease causes a dry hacking cough when stomach contents reflux into the distal esophagus via an esophageal-tracheobronchial reflex. Classically, associated with heartburn or sour taste in the mouth, more than 40% have no gastrointestinal symptoms. While proton pump inhibitor therapy can help in many patients, in others normalizing the pH has no impact on the cough. Generally, the cough occurs most frequently within an hour of lying down horizontally. Chest x-rays and auscultation of the lungs are normal.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors cause a dry hacking cough because they also interfere with the normal breakdown of bradykinins in the lungs. This leads to a stimulation of nitric oxide synthetase, which leads to a local accumulation of NO, an irritant to lung tissue, causing a characteristic cough. The cough is described as mild or hardly a cough at all. Some people feel a sensation in the throat and may seem to be clearing their throat. While incidences have been reported as high as 15%, many times subtle symptoms are overlooked and most literature lists an incidence between 3% and 10%. Like the GERD-induced cough, radiological and physical examination findings are negative. The cough usually occurs within a week to 6 months after initiating ACE inhibitors or increasing the dose. It typically stops within a week of discontinuation of ACE inhibitor therapy, but may take up to a month.

Pertussis (Whooping Cough)

Caused by the bacteria, Bordetella pertussis, whooping cough has recently increased in frequency in teenagers and adults because the vaccination only provides protection for about 10 years. Previously, pertussis vaccination was limited to infancy and a booster prior to elementary school because the antigen caused severe adverse effects in teens and adults. The availability of the new, less toxic to adults, acellular antigen in vaccines has enabled the current recommendation of vaccination for teens and adults to prevent the increasing incidence in these groups. While potentially fatal in unvaccinated infants, pertussis presents in a much milder form in adults and teens, without the classical “whoop” seen in infants. It typically presents as a dry hacking cough. Over 90% of adults have violent coughing spasms that can leave patients breathless after the coughing spasm. Over 80% cough during the night, and over one-third have at least one vomiting episode due to a coughing spasm. The cough can last up to 8 weeks. The chest x-ray is negative as is auscultation of the lungs in most patients. In some patients, inspiratory stridor or expiratory wheezes can be heard. Fever is either low grade or absent. Pertussis currently is the primary non-viral cause of acute bronchitis in adults and teenagers, representing less than 10% of all acute bronchitis infections.

• ACUTE/SUBACUTE/CHRONIC COUGH WITH MIXED OR VARIABLE PRODUCTIVITY

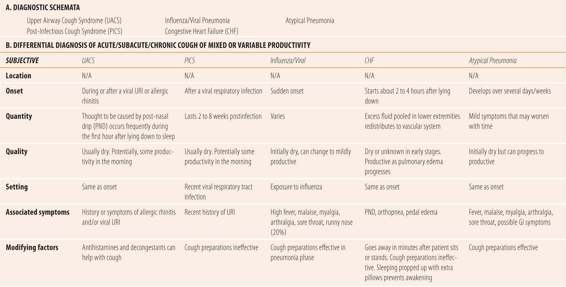

Upper Airway Cough Syndrome (Post-Nasal Drip)

Any disease that causes post-nasal drip can cause a cough (see Table 8.3). Usually dry and nonproductive during the day, accumulation of drying discharge overnight can produce some nominal mucous during the first few coughs in the morning. Most patients with upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) have a recent history or signs and symptoms of either allergic rhinitis or a viral URI. The cough is most notable in the first hour immediately after lying down for sleep due to drainage from the sinus cavities and into the throat. Physical examination of the lungs is negative.

| TABLE 8.3 | Acute/Subacute Mixed/Variable Productivity Cough |

Post-Infectious Cough Syndrome

Viral respiratory infections that involve the lower respiratory tract can result in a lingering cough lasting 2 to 8 weeks’ with few physical findings consistent with infection. While the exact mechanism is unknown and probably multifactorial, the viral infection is thought to create enough irritation and inflammation to cause the cough to continue long past the presence of an infectious process. The continuing cough is the result of bronchial hypersensitivity and hyperresponsiveness manifested as a cough. In one study of 184 adults with subacute cough, 82% had either post-infectious cough syndrome (PICS) or UACS. Physical findings are minimal. If a cough lasts more than 8 weeks, then further diagnostic workup is warranted, looking for chronic causes including asthma, allergic rhinitis, TB, and cancer.

Influenza/Viral Pneumonia

Viral pneumonias represent about 20% of community-acquired pneumonias in adults and a much higher percentage in children. Influenza is the most common and best studied viral infection. Other common causes are respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, parainfluenza, and coronavirus. The presentation is quite variable, ranging from influenza with abrupt onset, severe systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, aches pains, and chills. The development of a cough due to other viruses causes milder symptoms, and the illness evolves more slowly with many having symptoms of a viral URI as the initial presentation. Leukocytosis with a neutrophilic response and elevated serum procalcitonin levels are uncommon.

Congestive Heart Failure

In older patients with a long history of hypertension or coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure can be a cause of cough. Typically, fluid accumulates as edema in the lower extremeties during the daytime. Approximately 2 to 3 hours after laying down, the edematous fluid redistributes itself in the vascular compartment, overcoming the failing heart’s pumping capability and causing fluid to leak into the lungs. Patients wake up coughing, and/or short of breath several hours after retiring. Sitting up or standing up causes the excess fluid to repool in the periphery, reducing cardiac workload and causing the symptoms to go away. This is called paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or PND. Patients realize over time that sleeping propped up with several pillows or sleeping in a recliner prevents those nocturnal events. That is called orthopnea and is typically described in terms of the number of pillows required to sleep (e.g., three pillow orthopnea). The cough can range from dry to productive depending on the severity of the heart failure with frank pulmonary edema presenting with a productive cough. Physical examination of the lungs in the early stages is generally normal except for cardiac enlargement upon percussion and peripheral edema due to excess fluid. Once pulmonary edema occurs at any posture, crackles in both lungs or absent breath sounds predominate physical findings along with a productive cough.

Atypical Pneumonia

Atypical pneumonia was coined to describe pneumonias that presented differently from typical bacterial pneumonia. While Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, and Legionella species are usually included in the definition of atypical. Also many experts include viral and other bacterial or rickettsial pathogens. All three primary agents are bacterial but do not cause the classical symptoms or responses of bacterial pneumonia. Because of its relative lack of acuity, atypical pneumonia has been referred to as “walking pneumonia.” Atypical pathogens represent almost 25% of the causes of community-acquired pneumonia in adults.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is most common in school-aged children and young adults. The onset of illness is gradual and initial symptoms may include headache, malaise, and low-grade fever. Patients generally feel worse than physical findings would indicate. The cough is usually nonproductive to mildly productive and symptoms involving the upper respiratory tract while not typical are not uncommon. The white blood count is normal in the vast majority of patients, but in severe disease the body does mount a neutrophilic response typical of bacterial pneumonias. Chest x-ray abnormalities are typically feathery rather than consolidated infiltrates.

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is a less frequent cause of atypical pneumonia, but parallels Mycoplasma in terms of clinical presentation. C. pneumoniae differs from Mycoplasma in its 21-day incubation period and the presence of laryngitis in most patients as a typical symptom.

Legionella infections are the least common atypical pathogen. Clinical presentation most closely resembles that of classical bacterial pneumonia with the exception of minimal to mild sputum production. Legionella infection should be suspected in patients with pneumonia accompanied by a high fever (>39°C), gastrointestinal symptoms, especially diarrhea, a Gram stain of sputum that reveals lots of neutrophils but no bacteria. Smokers, patients with chronic lung disease, or immunosuppressed patients are at higher risk. Elevated liver function tests are also a common finding. Radiologically, Legionella infections tend to be more like bacterial pneumonia. Urinary antigens can be diagnostic for the main serotype but vary with severity of disease.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Gonzales R, Sande MA. Uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:981-991.

2. Horsburgh CR, Rubin EJ. Latent tuberculosis infection in the united states. N Engl J Med. 2011;364: 1441-1448.

3. Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic review: T-cell based assays for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:177-184.

4. McCool FD. Global physiology and pathophysiology of cough. Chest. 2006;129:48S-53S.

5. Pratter MR. Overview of common causes of cough. Chest. 2006;129:59S-62S.

6. Kwon NH, Oh MJ, Min TH, Lee BJ, Choi DC. Causes and clinical features of subacute cough. Chest. 2006;129:1142-1147.

7. Goldsobel AB, Chipps BE. Cough in the pediatric population. J Pediatr. 2010;156:352-358.

8. Chung KF, Pavord ID. Chronic cough 1: prevalence, pathogenesis and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364-1374.

9. Eversten J, Baumgardner DJ, Regenry A, Banerjee I. Diagnosis and management of pneumonia and bronchitis in outpatient primary care practices. Prim Care Resp J. 2010;19:237-241.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree