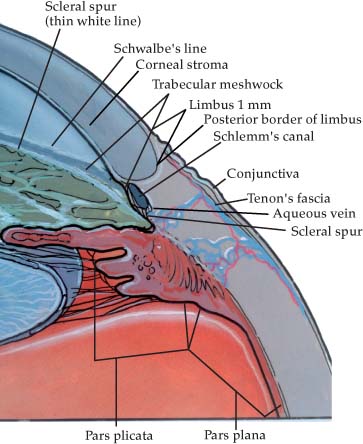

Chapter 23 The cornea, even though it is the window to the eye, like Rodney Dangerfield, often gets little respect! Ignorance is bliss until the cornea is not clear preoperatively, in which case doing surgery through a “dirty window” can be difficult, indeed; and, if the cornea is unclear after surgery, it may be too late to consider what damage might have occurred at the time of surgery. In fact, it is fair to say that the best phacoemulsification that could possibly be done is meaningless if permanent corneal damage occurred. In this era of technically advanced phacoemulsification, pseudophakic bullous keratopathy is almost considered a problem of the past; however, it continues to be a leading indication for penetrating keratoplasty,1 and surprisingly it can be easily induced among the un-wary. Those of us who specialize as “window cleaners” may have a few pieces of advice worthy of consideration for any phacoemulsification surgeon. To appreciate these problems a general review of corneal anatomy may be helpful. The cornea measures 12 mm horizontally and 11 mm vertically. The thickness varies from 1 mm at the periphery to 0.5 mm centrally. Viewed from the front it appears elliptical with an average radius of 7.8 mm; viewed from behind, it appears circular with an average radius of 6.8 mm. Centrally the cornea consists of five layers: Epithelium: The corneal epithelium is stratified, squamous, nonkeratinized epithelium five to seven cell layers (50 μm) in thickness. The deepest layer of cells are the basal cells, which are arranged in a single layer. They have flat bases and rounded heads with large oval nuclei lying near the head. The basement membrane lies between the basal cells and Bowman’s membrane. It is thin and difficult to visualize, but plays an important role in epithelial cell adhesion. The basal cells adhere to their basement membrane by a combination of desmosomes, adherens junctions, tight junctions, and gap junctions. Bowman’s membrane: This membrane is an acellular connective tissue layer composed of thin collagen fibrils aligned randomly in a ground substance. It will merge into the highly organized corneal stroma. It is 10 μm thick. Stroma: The stroma constitutes 90% of the corneal thickness. It is highly ordered and is composed of layers of cylindrical collagen fibrils embedded in a ground substance. The fibrils are arranged parallel to Bowman’s membrane and crisscross at right angles interlacing only slightly. Between the lamellae are two types of cells, keratocytes (fixed cells), and wandering cells, which appear to be phagocytic. Descemet’s membrane: This membrane is a highly ordered network of very thin homogeneous collagen filaments about 10 μm thick in adults. It is slightly thicker in the periphery than centrally. The thickness increases with age. It is the basement membrane for the endothelium. Endothelium: The endothelium is a single cell layer 3 μm thick. Each cell is anchored to its neighbor by interdigitations of the cell surfaces. Due to the close binding of cells, the endothelium can be stripped off in a sheet. The limbus, approximately 1 mm wide, marks the transition between the cornea and sclera. It is important anatomically because a wide variety of surgical incisions pass through this structure. The cornea joins the sclera in a curved margin, leading to confusion in the nomenclature used for the true limbus. For the purposes of this discussion, the limbus will be defined as extending from a line drawn between the end of Descemet’s and Bowman’s membranes to the point where corneal stroma merges into sclera. As the epithelium transitions from cornea to conjunctivae, it thickens rapidly to 10 or more layers. There are interdigitations of loose connective tissue papillae 1 to 2 mm apart running from the sclera to the cornea, where they are lost in the clear cornea. Blood vessels and lymphatics run in these papillae. The stroma loses the regular orientation of the cornea and resembles ordinary connective tissue. The limbus is abundantly supplied by the superficial marginal plexus of blood vessels created by episcleral branches of the anterior ciliary vessel and conjunctival vessels. Lymphatics run in the same distribution. Sympathetic nerve fibers supply the vascular plexus at the limbus. In addition, sensory fibers from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve enter the limbus from the perichoroidal space and, after losing their myelin sheaths, branch into the corneal stroma, penetrating Bowman’s membrane and ending as naked fibrils between epithelial cells. FIGURE 23–1 The anatomic relationships of the cornea and limbus. Viewed through the surgical microscope, with the conjunctiva reflected so that the limbus is visible, the posterior limbus is visualized as a line of demarcation between the bluish semitransparent limbal stroma and the opaque white sclera. An incision made perpendicular to the surface of the stroma at this junction will be in avascular limbal stroma, entering the anterior chamber in front of Schlemm’s canal and just behind the termination of Descemet’s membrane, passing through the anterior aspect of the trabecular meshwork. An incision made perpendicular to the cornea at the junction of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium will enter the anterior chamber, penetrating Descemet’s membrane and the endothelium anterior to the trabecular meshwork. So, what is the problem? If the cornea is densely scarred, a corneal transplant needs to be done before cataract surgery or at the time of cataract surgery; if the scarring is minimal, adequate visualization should not be a problem. Generally, if the expected postoperative visual acuity is 20/30 or better due to corneal problems, why do a transplant if cataract surgery alone can result in exceedingly quicker and more guaranteed visual rehabilitation? The line to draw for visual acuity as an indication for keratoplasty is variable depending on the pathology (stable or getting worse) and is patient specific. At 20/60 or worse corneal acuity, a transplant is usually needed. Certainly, a corneal problem that will allow good visual acuity shouldn’t be difficult in the hands of an experienced phacoemulsification surgeon. There is a new twist to consider, however. In a combined procedure a limbal or corneal self-sealing incision at the same time but prior to the penetrating keratoplasty is increasingly being seen as a better way to proceed. Expulsive hemorrhage, a frequent complication associated with prolonged open-sky techniques, is totally avoided by a closed, sealed phacoemulsification. Furthermore, an intact capsulorrhexis with a perfect placement of an in-the-bag intraocular lens is also immensely easier in the closed phacoemulsification system. Probably the biggest problem associated with open-sky surgical technique is the collapse of the capsular bag around the cortex and the difficulty in getting a complete cortex cleanup, often in the face of a bulging posterior capsule. This also is avoided by a closed system, which opens the capsular bag and makes cortex removal much simpler. Combine this with a foldable lens and the overall time for the phacoemulsification/intraocular lens insertion is often less than the time it takes to do a nucleus expression with a good cortical cleanup in an open-sky system. Thus, this combination makes a lot of sense. Now, however, one has to deal with a cornea that is unclear, and therefore all tricks on visualization are extremely important if the phacoemulsification is going to be successful. Here is how I handle the visualization conundrum for the following specific diagnoses. Bullous keratopathy severe enough to warrant penetrating keratoplasty is very aggravating in regard to visualization! Interestingly, the operating microscope allows better visualization than one might expect, in particular if it is aligned slightly off the direct axis so that the disconcerting reflections are not bouncing directly back into the surgeon’s eyes. An irregular epithelium can often be smoothed out with a cohesive viscoelastic. In cases of advanced Fuchs’ dystrophy, removing the epithelium usually will work surprisingly well. In regard to the light level, higher is not necessarily better, and one must adjust the light for optimal visibility, which can vary during capsulorrhexis and be slightly different during phacoemulsification. Because there is usually no clear zone of the cornea, it is particularly important that “blind” maneuvers not be carried out with bullous keratopathy cases. Being a fan of the phaco chop, I find that using my chopping instrument to manipulate and move pieces well away from the capsule before any emulsification is carried out is much safer and ensures that the procedure is carried out without inadvertent capsular breakage. This is one time that being near the cornea doesn’t matter. I am always certain about my safe zone when visualization is poor during each step of the procedure! With experience, phacoemulsification can be easy even with significant corneal edema. There are some cases in which the visualization is poor. Therefore, when in doubt, convert to open-sky extracap. I will remove the epithelium and smooth out the anterior stromal surface with viscoelastic prior to advancing to penetrating keratoplasty and open-sky cataract extraction, however, and I find that this final step is often enough to safely be able to carry out phacoemulsification. In almost all instances in advanced herpes simplex keratitis or status post–corneal ulcer, there are variable clear zones of the cornea that can provide excellent visualization. Pick the clearest zone and use that for most nucleus removal maneuvers. In a cooperative patient this procedure is often best done with topical anesthesia so that the patient can maneuver the eye and help with best visualization during the procedure. The beauty of a self-sealing incision is that the retrobulbar anesthesia can be carried out at the end of phacoemulsification for the penetrating keratoplasty without difficulty. Other tricks, as pointed out in the preceding bullous keratopathy section, can be used such as decreasing the light to optimize the view and making sure that incident light is not a problem by tilting the microscope body in relation to the corneal plane. These procedures can be done with topical anesthesia. Most patients with keratoconus who also have a cataract are older and provide dramatically varying visualization depending on where they are looking and which part of the cornea is used as the window. For most patients, looking slightly below the light and viewing through the superior part of the cornea allows a very good view for lens removal. Most of these cataracts are not advanced and can be removed quite easily. In general, these cases are usually the easiest to carry out by phacoemulsification prior to keratoplasty even when visual acuity is markedly decreased. Although epithelial irregularity is rarely an indication for keratoplasty, it certainly can be a visualization concern. This problem can be encountered in some susceptible patients, especially with topical anesthesia, due to a combination of exposure and marked epithelial toxicity. In many such cases there is a clear view immediately after wetting the corneal surface, but in a matter of seconds the view degrades and can seriously hamper visualization even more than the classical corneal problems already discussed! This problem is very easy to control by a viscoelastic resurfacing of the corneal surface. The technique I have found most successful is to place 15 to 20 microdots of a dispersive viscoelastic (so far I have found Viscoat to be the most effective). These little microdots coalesce with a little balanced salt solution; use the tip of the irrigating cannula with the salt solution to smooth any visible irregularities until there is a clear surface. To maintain this viscoelastic surface, it is important to wet only as needed because frequent wetting can irrigate the surface away and destroy what you are trying to create. If, however, this surface effect is destroyed, it can always be re-created using minimal amounts of viscoelastic. This technique is much preferable to just putting a glob of viscoelastic on the surface, which produces a lot of irregularity, wastes a lot of viscoelastic, and often takes a long time before it smooths out and allows an undistorted view of the anterior segment. Another advantage to this technique is that it avoids copious topical irrigation, which can wash topical anesthesia away and thereby decrease the overall pain-free time in topical cases! Some limbal corneal pathologies can be quite profound and result in a large band of extremely poor visualization of the anterior segment. This is a much greater problem for surgeons who approach cataracts from only the superior approach. Flexibility is the key, and the best approaches to this specific problem are from the superotemporal, nasal, and inferotemporal directions to minimize the limbal pathology’s effect on visualization. A temporal approach allows a larger viewing area because the distance from the visual axis to the limbus is the greatest temporally and the least superiorly. A topical anesthetic in a cooperative patient is also very helpful in that the patient can pick a spot to the side of the operating light and usually move this limbal pathology out of the way. If a retrobulbar is used, a two-handed technique using a second instrument through the side port also allows the eye to be moved in any direction with complete control to optimize visualization. Band calcification is often difficult to judge in regard to the impact it might have on visualization at the time of cataract surgery. Limbal band calcification can be handled as outlined above for the arcus; however, if the calcification approaches and crosses the visual axis, the slit-lamp test is usually the best way to decide whether it needs to be dealt with preoperatively or can be ignored. If looking through the central cornea with the slit beam closely lined up with the oculars, and if iris detail is easily visualized, cataract surgery can be carried out generally without difficulty. All of the pearls already outlined, in particular topical surgery in a cooperative patient, will help ensure that visualization will be safe outside the area of the band. An ethylenediaminetetraacetic (EDTA) scrub is simple and effective; however, if there is any question about what to do, removing the central band prior to surgery is the best approach. Allow at least 6 weeks, in that epithelial irregularity, even though visualization for surgery might be fine, can throw biometry off. A second advantage to the EDTA scrub is improved biometry, in that very bizarre keratometry readings can occur where the band is present. With a little experience, phaceoemulsification can be completed successfully and safely for a large array of corneal pathologies, which allows for a safer combined procedure and gives cataract surgeons optimal flexibility of doing cataract surgery where the expected visual acuity from the corneal pathology is still quite good. I am convinced that more and more corneal surgeons will find phacoemulsification the best way to proceed in combined procedures rather than the difficult and often unsatisfactory open-sky approach to cataract surgery. This common corneal problem has a female preponderance and is age related, becoming increasingly common in the seventh and eighth decades of life. Although familial patterns do appear, the genetics are still controversial! The clinical hallmark, well known by ophthalmologists, is guttata. These excrescences on Descemet’s membrane are a sign of endothelial stress. More advanced signs are increasing stromal thickness leading to folds in Descemet’s membrane and then frank epithelial edema.5 Moderate to advanced Fuchs’ dystrophy can be diagnosed without difficulty. The problem is that guttata alone does not make the diagnosis of Fuchs’ dystrophy. Many elderly patients have guttata and yet exhibit no specular microscopic or pathologic findings of Fuchs’ dystrophy. A thickened posterior collagen layer of Descemet’s is the hallmark of this condition, and, to make things complicated, some cases of Fuchs’ dystrophy thicken this posterior collagen layer in a relatively smooth fashion (so-called guttataless Fuchs’). To the unwary it can be missed entirely as a diagnosis prior to surgery!

CORNEAL PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED

WITH PHACOEMULSIFICATION

CORNEAL ANATOMY2–4

LIMBAL ANATOMY2–4 (Fig. 23–1)

VISUALIZATION DIFFICULTIES

BULLOUS KERATOPATHY

STROMAL CORNEAL SCARRING

IRREGULAR CORNEAL SURFACE (SUCH AS KERATOCONUS)

EPITHELIAL IRREGULARITY (SUCH AS AN EPITHELIAL DYSTROPHY)

ARCUS

BAND KERATOPATHY

CATARACT SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH FUCHS’ CORNEAL DYSTROPHY (TABLE 23–1)

Diagnosis Overt guttata Guttataless Thickening of posterior collagen layer of Descemet’s membrane Subtle guttate on careful examination under high slit-lamp power Previous trauma with decreased cell counts Specular microscopy to confirm diagnosis |

Phaco technique Low flow/low power to create many small nuclear pieces to minimize phaco power Small capsulorrhexis to isolate phaco energy from endothelium/phaco within the capsular bag Dispersive viscoelastic BSS+ Minimal irrigation and aspiration (I&A) of viscoelastic at the end of the procedure; Diamox sequel for possible intraocular pressure (IOP) spike |

GUTTATALESS FUCHS’

Before exploring these two questions, guttataless Fuchs’ warrants some discussion because it can be a difficult reminder of how fickle the cornea can be. I have seen several cases from excellent cataract surgeons who state that they have used their usual technique with unexpected profound corneal edema, which later was shown to be due to Fuchs’ dystrophy. I have never seen a case of guttataless Fuchs’ that did not have other indications of a problem, often with a lot of subtle guttata. What I have seen, however, on cursory examination could easily have been missed. Many of these patients have gone on to penetrating keratoplasty, and the diagnosis of Fuchs’ dystrophy can be verified. Part of the routine corneal slit-lamp examination should include a careful high magnification scanning of the endothelial surface looking for subtle guttata. Some Descemet’s folds and increased stromal thickness are other warning signs. In this case an ounce of concern can lead to a prepared and much happier patient and surgeon!

A related condition is severe blunt trauma that has compensated and results in a normal-looking cornea. If the cataract looks traumatic, it is well worth a little discussion with the patient on the subject. Some of these patients may have had trauma when they were so young that they don’t remember the event. For example, my uncle was counseled about his cataract, and I was certain trauma had occurred. It was my father who remembered hitting him in that eye with a snowball with a rock in it when they were children. Interestingly, with specular viewing, the endothelial count was substantially decreased in this eye—a fact well worth knowing prior to surgery.

Trauma can result in a profound decrease in endothelial density. In fact, routine specular microscopy may be indicated simply to rule out these outliers prior to surgery, although the opposite case can be made—that outliers are so infrequent they are not worthy of a routine reimbursement. But it is good to know ahead of time what we are dealing with, and in regard to my cataract technique, I treat such cases as though they had Fuchs’ dystrophy.

In answering the question of combined approach versus cataract surgery alone, what do we do with such corneas? The key is to remember that penetrating keratoplasty results are quite good, but the recovery is prolonged, and spherical and astigmatic errors are still common. Although it does definitively get at the corneal problem, it is a significantly more difficult postoperative travail for the patient. Also, we now have cataract removal techniques that create minimal additional corneal damage and therefore are much less likely to tip the patient into significant corneal edema. My approach is very simple: If there is no epithelial microcystic edema other than minor early morning changes that resolve spontaneously on their own shortly after arising, I proceed with a phacoemulsification and intraocular lens (IOL) insertion alone regardless of the corneal thickness. Many patients do well with this approach. Many patients in whom I previously did penetrating keratoplasty are now successfully handled with acceptable visual acuity results by cataract surgery alone. A careful informed consent discussion should include that a corneal transplant is possible as a secondary procedure. The key is performing cataract surgery in ways that will minimize the endothelial damage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree