Cooper Ligament Repair of Groin Hernias

Robb H. Rutledge

The Cooper ligament repair (McVay repair) is the only anterior herniorrhaphy that repairs all of the hernia defects that occur in the groin. Although this repair gives excellent results, it has been largely superseded by the less invasive “tension-free” repairs in which patients have a quicker recovery.

The Cooper ligament technique requires more extensive dissection, and the patients have more early pain and disability. However, there is no difference in late pain or disability between patients with a Cooper ligament repair and one of tension-free repairs. It remains an excellent, if infrequently used, choice when a posterior wall reconstruction is performed.

Historical Background

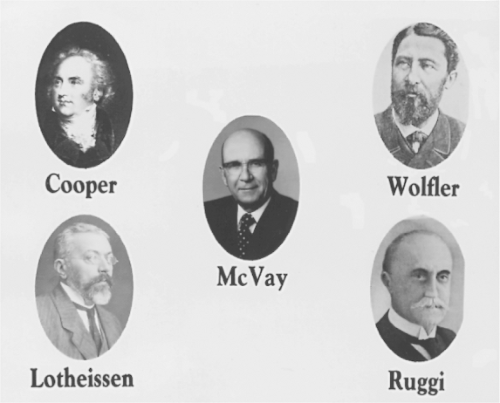

Astley Cooper’s curiosity about hernias was piqued by the fact that he himself had a hernia as a teenager. He wore a truss for 5 years and apparently had no further trouble. In 1804, he published his classic work on hernias in which he demonstrated the anatomic defects of groin hernias, described the transversalis fascia, and defined the superior pubic ligament that later bore his name. Anesthesia and asepsis were unknown then, and Cooper recommended surgery only to repair incarceration or strangulation. He did not use the Cooper ligament in his repairs. Sir Astley’s truss apparently was successful, because his autopsy revealed only the fibrotic remains of a right indirect inguinal hernia.

Guiseppe Ruggi was the first to use the Cooper ligament in any type of hernia surgery. In 1892, he sutured the inguinal ligament down to the Cooper ligament to repair femoral hernias.

In 1897, Georg Lotheissen was the first to perform what is currently considered to be a Cooper ligament or McVay repair. He was operating in Innsbruck on a 45-year-old woman with a twice-recurrent inguinal hernia after previous Bassini repairs. He found that the inguinal ligament was destroyed, so he anchored the conjoined tendon to the Cooper ligament instead. He subsequently reported success with this technique for inguinal and femoral hernias, but he did not use a relaxing incision.

In 1939, Chester McVay submitted his thesis on the anatomy of the groin for his doctorate at Northwestern University. He pointed out that the normal insertion of the transversus abdominis and the transversalis fascia was on the Cooper ligament, not the inguinal ligament. From his dissections, McVay developed his technique of groin hernia repairs and reported this in 1942 while he was a surgical resident at the University of Michigan. He was unaware of Lotheissen’s work then. McVay emphasized that the Cooper ligament was the anatomically correct anchor for a posterior wall reconstruction and recommended his repair for direct, large indirect, and femoral hernias. He used a relaxing incision to minimize tension. McVay’s work provided a sound anatomic basis for this technique and popularized its use in America, where it is known equally well as a McVay repair or a Cooper ligament repair.

A relaxing incision is an essential part of a Cooper ligament repair. Although Anton Wolfler did not use the Cooper ligament in his hernia surgery, he is given credit for making the first relaxing incision. In 1892, in the Festschrift for Theodor Billroth, Wolfler described making an incision in the anterior rectus sheath whenever he noted tension approximating the conjoined tendon to the inguinal ligament. He did this to relieve tension and gain access to the rectus muscle to transplant it to reinforce the repair (Fig. 1).

Anatomic Basis for A Cooper Ligament Repair

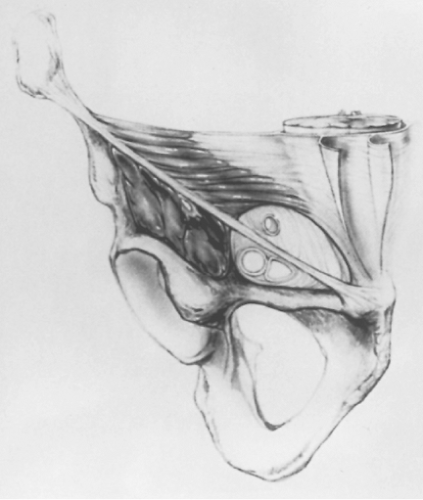

A strong posterior inguinal wall is the best protection against a groin hernia in an adult. Normally, this is provided by the insertion of the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and the underlying transversalis fascia onto the Cooper ligament from the pubic tubercle to the medial margin of the femoral ring laterally.

There is a wide variation in the length of the insertion of the transversus abdominis on the Cooper ligament. In approximately 75% of McVay’s dissections, this was a long insertion with a broad aponeurotic plate, giving a strong posterior wall that is unlikely to develop a direct hernia. In the remaining 25%, the insertion was short, and the continuity of the posterior wall was

made up only by the transversalis fascia, which made the wall potentially much weaker.

made up only by the transversalis fascia, which made the wall potentially much weaker.

Fig. 2. Anterior view of the myopectineal orifice of Fruchaud. See text for boundaries. (From Wantz GE. Atlas of Hernia Surgery. New York: Raven, 1991:4, with permission.) |

In 1956, Fruchaud called this weak area of the posterior wall—composed only of transversalis fascia—the myopectineal orifice. It is bounded by the rectus muscle medially, the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles superiorly, the iliopsoas muscle laterally, and the Cooper ligament and pubis inferiorly. It is spanned and divided by the inguinal ligament, traversed by the spermatic cord and femoral vessels, and bridged on its inner surface by only the transversalis fascia (Fig. 2).

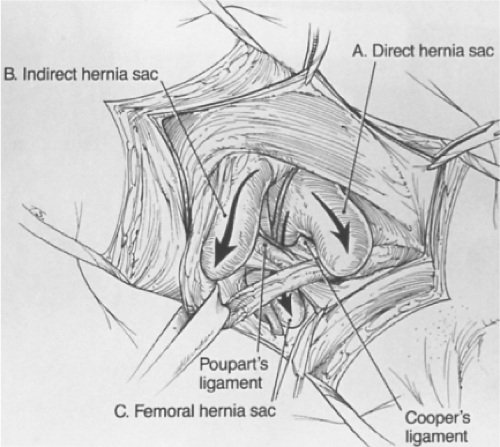

All groin hernias begin as a weak area in this myopectineal orifice. With a decrease in aponeurotic fibers in this area from defective collagen metabolism (e.g., from smoking) and a gradual attenuation from increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., from prostatism, constipation, or chronic lung disease), a hernia can result. The transversalis fascia deteriorates and allows a peritoneal protrusion through it. Depending on the length of the insertion of the transversus abdominis on the Cooper ligament, the presence of a patent processus vaginalis, and the width of the femoral ring, the hernia might be direct, indirect, femoral, or any combination of the three (Fig. 3). Groin hernias are corrected by repairing all or part of the myopectineal orifice or by substituting a prosthesis for the deteriorated transversalis fascia.

Currently, hernia repairs can be divided into two main groups: (a) those that close all or part of the myopectineal orifice by suturing the tissues at its boundaries (Cooper ligament, Shouldice, and Bassini) and (b) those that merely cover the unclosed orifice with prosthetic mesh (Lichtenstein, plug and patch, and laparoscopic). The Cooper ligament method is the only anterior open repair that closes the complete myopectineal orifice.

A Cooper ligament repair should be considered whenever a posterior inguinal wall reconstruction is performed. McVay used this repair for direct, large indirect, and femoral hernias. He did not recommend the operation for small or medium indirect hernias, believing that a posterior wall reconstruction was unnecessary in these cases.

Using this selective approach, McVay reported in 1958 a recurrence rate of 3.2% for abdominal ring repairs for small or medium indirect hernias, but only a 0.85% recurrence rate for Cooper ligament repairs for the more difficult direct, large indirect, and femoral hernias. McVay’s report is one of the few that has a higher recurrence rate for the easier indirect hernias than for the more difficult direct ones. A more complete repair on the small and medium indirect hernias should improve the results.

Because of McVay’s report, in 1959 I began doing and continued to do a Cooper ligament repair on all groin hernias in adults, primary or recurrent, regardless of the presenting type. Approximately 15% to 20% of patients have multiple ipsilateral defects at the original operation. Most recurrences are due to missed hernias, inadequate dissection, or subsequent further deterioration of the transversalis fascia. All the types of groin hernias present within inches of each other. Recurrences should be less if all possible defects are repaired and the myopectineal orifice completely closed at the original operation.

Presently, the vast majority of surgeons perform some type of “tension-free” mesh repair as their preferred technique. However, not all patients require or are suitable for prosthetic mesh. A Cooper ligament repair remains an appropriate choice in patients who need a posterior inguinal wall reconstruction.

A complete history and physical examination are performed, and a careful search is made for other disease before the hernia is repaired. Cardiac and pulmonary consultations are occasionally indicated. The prostate is examined, and urinary symptoms are noted to see if they take precedence or should be treated at the time of the hernia repair. Occasionally, but not routinely, the patient has radiologic or endoscopic examinations to rule out coexisting colorectal disease.

During the physical examination, the opposite groin is carefully checked. If a contralateral hernia is found, a bilateral repair is usually performed. The testicles are palpated to be certain of their status before surgery.

Surgical Management

Before operation, all patients are told of the possible use of Marlex mesh and the possible sacrifice of the ilioinguinal nerve. All male patients are told of the possible occurrence of ischemic orchitis and subsequent testicular atrophy, regardless of careful technique.

General anesthesia has been used routinely, but local or regional anesthesia would be satisfactory. Perioperative antibiotics are given, and the bladder is emptied immediately preoperatively. An identical repair is performed whether the hernia is primary or recurrent, direct, indirect, or femoral. More detailed remarks about recurrent hernias, bilaterality, relaxing incisions, the femoral vessels, and testicular problems follow under Special Considerations.

A low almost transverse incision is made. The external oblique is opened through the external ring. Small hemostatic clips mark the boundaries of the external ring as a guide for the new external ring diameter. The ilioinguinal nerve is usually preserved, but I clip and divide it laterally if I believe it has been injured during the surgery. The spermatic cord is mobilized in the canal but is not disturbed medial to the pubic tubercle to preserve testicular collateral circulation.

The posterior wall of the inguinal canal is incised, completely destroying the internal ring. The iliopubic veins are controlled, and the Cooper ligament is dissected free (Fig. 4A). The spermatic cord is retracted superiorly with a broad Deaver retractor, and the deeper portion of the Cooper ligament is cleared (Fig. 4B).

Then, starting lateral to the femoral vessels, the femoral sheath (anterior femoral fascia) is identified and dissected free. Working medially, the anterior surface of the femoral artery and vein are seen and cleared off as the femoral sheath is developed. The dissection continues medially, and the fat and lymph nodes are removed from the femoral canal. Any femoral sac is converted to an inguinal one. Finally, any vascular connections to the obturator circulation are divided and ligated so they are not torn during the repair.

After the inferior dissection is completed, the transversus abdominis arch is mobilized superiorly from the underlying preperitoneal tissues, and any attenuated transversalis fascia and internal oblique are excised. Then, a relaxing incision is made at the point of fusion of the external oblique aponeurosis and the anterior rectus sheath. This starts at the pubic tubercle and extends superiorly for approximately 4 to 5 inches (Fig. 4C).

The patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position to decrease the likelihood of intestinal injury. The spermatic cord is opened, and the cremaster fibers are divided at the internal ring (Fig. 4D). Any fat or lipoma is removed from the cord. The external spermatic artery is divided as it comes off the inferior epigastric so the cord can be moved laterally during the repair (Fig. 4E).

Indirect sacs are opened and explored to evaluate any intra-abdominal pathology and to be certain that no intestine is adherent directly under the area of the repair. Small indirect sacs are removed and the peritoneum closed. Large indirect sacs are transected just distal to the internal ring. The proximal sac is freed from the cord by sharp dissection and closed. To decrease the chances of developing an ischemic orchitis, the distal sac is left in place and filleted on its anterior surface to prevent hydrocele formation. If no indirect sac is apparent, the anteromedial portion of the cord is dissected superiorly to identify and ligate the small peritoneal tab that is always present to avoid overlooking an indirect sac.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree