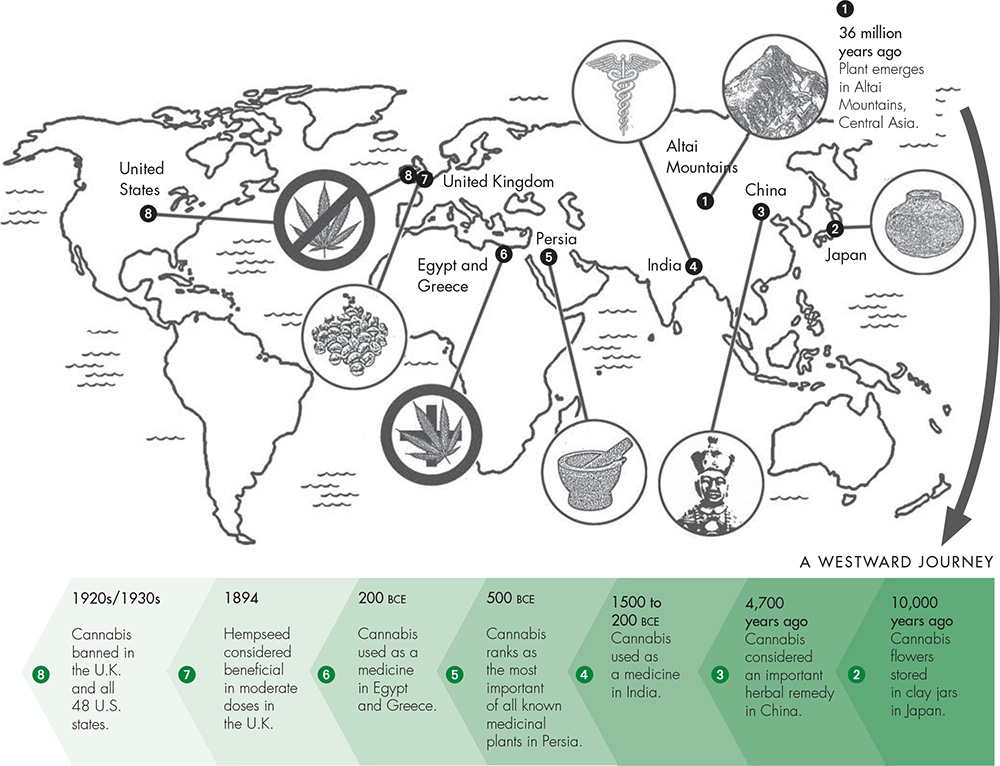

Humans may have cultivated cannabis for longer than any other plant. It has been grown for fiber, medicine, and inebriation for at least 12,000 years, since the end of the last Ice Age. The cannabis plant is believed to have first emerged around 36 million years ago in Central Asia, near the Altai Mountains, where Siberia, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan converge. Forty-thousand-year-old human remains have been found in the Altai region, so cannabis plants growing along the region’s riverbanks may likely have first attracted human attention as a food source. The earliest extant evidence for cannabis usage are 10,000-year-old dried cannabis flower specimens: they were found in a clay jar at a Jomon-era Japanese archaeological excavation. According to researcher Dave Olson, “A neolithic cave painting from coastal Kyushu in southwest Japan depicts tall stalks with hemp-shaped leaves. Strangely dressed people, horses and waves are also in the painting, perhaps depicting the Korean traders bringing hemp to Japan. The hemp plant figure itself reflects the sun/plant image, similar to the hieroglyphic likenesses used by Mediterranean cultures.”1 The earliest written accounts of cannabis used as medicine originate in ancient China, where cannabis is part of the oral, generation-to-generation transmission of plant lore. This oral tradition extends back to the legendary Emperor Shen-Nung, who reigned 4,700 years ago. In his teachings, Shen-Nung cited cannabis as an important herbal remedy, along with ginseng and ephedra. Following Shen-Nung’s reign, Chinese medical traditions were passed along orally for the next 2,000 years. And by the first century CE, Chinese oral traditions concerning medicinal cannabis had expanded to cover over 100 medical conditions. This knowledge was incorporated into the first Chinese pharmacopeia, Pen-ts’ao Ching. “Ma-fên (fruits of hemp) . . . if taken in excess will produce hallucinations . . . If taken over a long term, it lightens one’s body.”2 From 1500 to 200 BCE, cannabis was used as a medicine in the Mediterranean region, in Egypt and Greece, and in India. In the Avesta, the religious text of Zoroastrianism of ancient Persia (now modern-day Iraq), cannabis was ranked as the most important of all known medicinal plants.3 Further, Polish anthropologist Sula Benet has claimed, controversially, that cannabis provided a key ingredient—q’neh bosm—in the holy anointing oil recipe recounted in the Hebrew Old Testament’s book of Exodus.4 In early Islamic medicine, cannabis is both lauded as widely useful and condemned as a poison. The great Persian physician Mohammad-e Zakariã-ye Rãzi (865–925 CE) cited a wide range of uses for cannabis as a medicine, while the tenth-century physician Ibn Wahshiyah, in his book On Poisons, claimed that the mere aroma of cannabis resin would kill within days of exposure.5 A photograph of a neolithic cave painting discovered in southwest Japan. Between the two tall hemp leaves, it is just possible to discern human and horse figures above the swirling waves. Until the seventeenth century, very little was written in the West about the medicinal uses of cannabis. In his oft-quoted Anatomy of Melancholy, the English scholar Robert Burton included “hemp-seed” in a laundry list of plant remedies for depression, and renowned herbalist Nicholas Culpeper included hemp as an anti-inflammatory in The English Physitian [sic]. It is interesting to note that both of these uses would have relied on English fiber cannabis varieties constitutionally low in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; the main psychoactive constituent in cannabis) and likely higher in cannabidiol (CBD), an excellent anti-inflammatory. In 1838, Cannabis indica was reintroduced to Western medicine by William O’Shaughnessy, an Irish physician working and teaching in India, who published a noted account of his experiments with the plant.9 In its usage in O’Shaughnessy’s India, cannabis—both as a medicine and an inebriant—was typically consumed orally, rather than smoked. The use of bhang (ground marijuana) in bhang lassi, a drink consisting of milk, spices, and cannabis, had been present in the Indian subcontinent for over 1,000 years. Interestingly, recipes for bhang lassi often call for up to an ounce of cannabis flowers and leaves. Such a recipe could easily deliver 200 milligrams of THC per cup of bhang—an enormous dose. So why doesn’t a glass of bhang lassi deliver a huge effect? Simply because bhang is typically not heated above the temperature at which THC acid becomes psychoactive. Since bhang lassi recipes call for first making a cannabis water tea, before folding in the milk, this means that few of the non-water-soluble cannabinoids will be extracted. Bhang lassi is intended to be mild in its effect, and its preparation method supports that outcome.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Pen-ts’ao Ching

Cannabis Travels West

Context

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree