opioid analgesics (this chapter and Ch. 19)

Slow gut transit, especially in young women

Hypotonic colon in the elderly

Laxatives

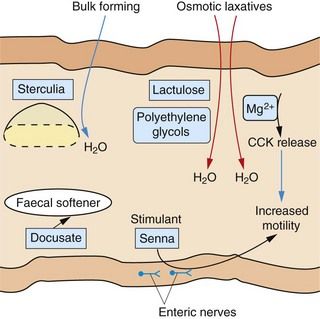

The mechanisms of action of common laxatives are shown in Figure 35.1. Some drugs have more than one mechanism, and they are classified by their principal action.

Fig. 35.1 Sites of action of the major classes of laxative drug.

Some laxative drugs have more than one mechanism of action. CCK, cholecystokinin.

Bulk-forming laxatives

Bulking agents include various natural polysaccharides, usually of plant origin, such as unprocessed wheat bran, ispaghula husk, sterculia and methylcellulose, all of which are poorly broken down by digestive processes. They have several mechanisms of action:

a hydrophilic action causing retention of water in the gut lumen, which expands and softens the faeces,

a hydrophilic action causing retention of water in the gut lumen, which expands and softens the faeces,Bulking agents take at least 24 h after ingestion to work. A liberal fluid intake is important to lubricate the colon and minimise the risk of obstruction. Bulking agents are useful for establishing a regular bowel habit in chronic constipation, diverticular disease and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but they should be avoided if the colon is atonic or there is faecal impaction.

Unwanted effects include a sensation of bloating, flatulence or griping abdominal pain.

Osmotic laxatives

Magnesium compounds such as the sulphate (Epsom salts) and the hydroxide are poorly absorbed from the gut and act as osmotically active solutes that retain water in the colonic lumen. They may also stimulate cholecystokinin release from the small-intestinal mucosa, which increases intestinal secretions and enhances colonic motility (Fig. 35.1). These actions result in more rapid transit of gut contents into the large bowel, where distension promotes evacuation within 3 h. About 20% of ingested magnesium is absorbed and inhibits central nervous system, cardiovascular and neuromuscular activity if it is retained in the circulation in large enough amounts, as can occur in renal failure. Magnesium hydroxide is a mild laxative, while the action of magnesium sulphate can be quite fierce, associated with considerable abdominal discomfort.

Lactulose is a disaccharide of fructose and galactose. In the colon, bacterial action releases fructose and galactose, which are fermented to lactic and acetic acids with release of gas. The fermentation products are osmotically active. They also lower intestinal pH, which favours overgrowth of some selected colonic flora but inhibits the proliferation of ammonia-producing bacteria. This is useful in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy (Ch. 36). Unwanted effects include flatulence and abdominal cramps. Lactulose can take more than 24 h to act.

Macrogols (polyethylene glycols) are large, inert molecules that are not absorbed from the gut and exert an osmotic effect in the colon. They are as effective as other osmotic agents, but their Na+ content may be hazardous for people with impaired cardiac function.

Sodium acid phosphate and sodium citrate are osmotic preparations that are given as an enema or suppository, usually for bowel preparation before local procedures or surgery.

Irritant and stimulant laxatives

Irritant and stimulant laxatives include the anthraquinones senna and dantron, and the polyphenolic compounds bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate. They act by a variety of mechanisms, including stimulation of local reflexes through myenteric nerve plexuses in the gut, which enhances gut motility and increases water and electrolyte transfer into the lower gut. Stimulant laxatives are useful for more severe forms of constipation, but tolerance is common with regular use and they can produce abdominal cramps. Given orally, they stimulate defecation after about 6–12 h.

Senna has the most gentle purgative action of this group. Given orally, it is hydrolysed by colonic bacteria to release the irritant derivatives sennosides A and B.

Senna has the most gentle purgative action of this group. Given orally, it is hydrolysed by colonic bacteria to release the irritant derivatives sennosides A and B. Dantron is available as co-danthramer, a combination with the surface wetting agent poloxamer 188, and as co-danthrusate, a combination with the mildly stimulant and faecal-softening agent docusate (see below). Dantron is carcinogenic at high doses in animals, and it is recommended that its use in humans should be limited to the elderly or terminally ill.

Dantron is available as co-danthramer, a combination with the surface wetting agent poloxamer 188, and as co-danthrusate, a combination with the mildly stimulant and faecal-softening agent docusate (see below). Dantron is carcinogenic at high doses in animals, and it is recommended that its use in humans should be limited to the elderly or terminally ill. Bisacodyl can be given orally or, for a more rapid action (15–30 min), rectally; it undergoes enterohepatic circulation.

Bisacodyl can be given orally or, for a more rapid action (15–30 min), rectally; it undergoes enterohepatic circulation. Sodium picosulfate is a powerful irritant and is given orally to prepare the bowel for surgery or colonoscopy. It generally acts in less than 6 h.

Sodium picosulfate is a powerful irritant and is given orally to prepare the bowel for surgery or colonoscopy. It generally acts in less than 6 h.The chronic use of stimulant laxatives has been suspected to cause progressive deterioration of normal colonic function, with eventual atony (‘cathartic colon’). It is now recognised that the condition probably arises from severe, refractory constipation rather than from the treatment.

Faecal softeners

Arachis oil can be given rectally to soften impacted faeces. Other drugs with faecal-softening actions include bulk-forming laxatives and docusate sodium. Liquid paraffin can be given orally, but is not recommended since it impairs the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins and can cause anal seepage with anal pruritus, and lipoid pneumonia after accidental inhalation.

Management of constipation

For simple constipation adopting a high-fibre diet, supplemented by bulking agents when necessary, is recommended. Exercise and an adequate fluid intake are also important. For short-term use, a stimulant laxative such as senna or bisacodyl can be taken orally at night to give a morning bowel action. Suppositories will give a more rapid effect. For longer-term therapy, regular magnesium salts or macrogols are usually well tolerated and effective.

Senna, magnesium salts and docusate appear to be safe in pregnancy. Bisacodyl, co-danthramer and co-danthrusate are suitable for the elderly or for the terminally ill with opioid-induced constipation. For opioid-induced constipation in terminal care, the peripheral opioid receptor antagonist methylnaltrexone can be added if laxatives are ineffective (Ch. 19). Lactulose is useful as a second-line agent and specifically to treat constipation associated with hepatic encephalopathy (Chs 36 and 56). For people in whom neurological disease affecting bowel motility is the cause of constipation, a faecal softener should be used, with regular enemas or rectal washouts.

Refractory idiopathic constipation is a condition almost exclusively found in women, starting at a young age. Long-term use of stimulant laxatives, often at high dosage, may be necessary. Bulk-forming laxatives are ineffective, and a high-fibre diet usually increases abdominal distension and discomfort. Prucalopride, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist (see compendium) is sometimes used for refractory chronic constipation. Biofeedback can help in up to 80% of people with the condition. For those who fail with these approaches, surgical intervention with colectomy may be the only option.

Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea is frequent watery bowel movements, with or without gas and cramping. Severe acute diarrhoea is usually a result of gastrointestinal infection, and it can be the consequence of both reduced absorption of fluid and an increase in intestinal secretions. Viral gastroenteritis is much more common than bacterial causes of diarrhoea in children, but viral and bacterial causes are both important in adults. Traveller’s diarrhoea is a particularly common problem because of exposure of the traveller to organisms which have not been encountered before. Common causes include enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli, Clostridium jejuni and Salmonella and Shigella species. Parasites such as Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium species and Cyclospora cayetanensis are less commonly involved. Diarrhoea may result from local release of bacterial enterotoxins, which have a variety of actions on gut mucosal cells, including stimulation of intracellular cAMP synthesis, which causes excess Cl− secretion into the bowel.

Drugs that can produce diarrhoea include magnesium salts (see above), cytotoxic agents (Ch. 52), α- and β-adrenoceptor antagonists (Chs 5 and 6) and broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs, which produce diarrhoea by altering colonic flora (Ch. 51). Antibacterial treatment can be associated with Clostridium difficile colitis.

Chronic diarrhoea requires full investigation for non-infectious causes such as carcinoma of the colon, inflammatory bowel disease and coeliac disease. Irritable bowel syndrome is often accompanied by increased frequency of defaecation, loose stool and a sensation of incomplete evacuation (see below).

Drugs for treating diarrhoea

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree