Chronic alcoholism is associated with a high incidence of peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy; sensory changes usually predominate.

Axonal degeneration, induced by alcohol or the alcohol metabolite acetaldehyde, or by nutritional deficiency, results in a typical symmetrical “glove and stocking” neuropathy that manifests with parasthesias, neuropathic pain, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and muscle weakness. Like all toxic and metabolic neuropathies nerve length determines the pattern of involvement: signs and symptoms begin in the feet and progress upward; the hands are not involved until the deficit in the lower extremities reaches the knee. Also, like the dysesthesias associated with other causes of neuropathy, pain is worse at night.

Central Nervous System

Wernicke’s encephalopathy, a manifestation of thiamine deficiency, refers to a triad consisting of oculomotor palsies, cognitive impairment, and ataxia.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy, a manifestation of thiamine deficiency, refers to a triad consisting of oculomotor palsies, cognitive impairment, and ataxia.

Thiamine (vitamin B1) is an essential cofactor for the enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. In the developed world thiamine deficiency affects principally chronic alcoholics although severe malnutrition from any cause may be associated with Wernicke’s encephalopathy. In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, before effective treatment, thiamine deficiency was occasionally noted, with Wernicke’s encephalopathy as the principal manifestation. The pathology includes petechial hemorrhages throughout the brainstem.

In vitamin-depleted alcoholics the administration of intravenous glucose may acutely precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy by increasing the demand for thiamine when the supply is limited.

In vitamin-depleted alcoholics the administration of intravenous glucose may acutely precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy by increasing the demand for thiamine when the supply is limited.

Glucose should never be administered to alcoholics without the concomitant administration of thiamine.

Glucose should never be administered to alcoholics without the concomitant administration of thiamine.

Bilateral sixth nerve palsy with failure of lateral gaze is the most common of the oculomotor manifestations and a defining characteristic of the syndrome although other oculomotor deficits may occur as well.

Bilateral sixth nerve palsy with failure of lateral gaze is the most common of the oculomotor manifestations and a defining characteristic of the syndrome although other oculomotor deficits may occur as well.

Both eyes crossed inwards results is a characteristic facial expression that reminds some observers of a Planaria worm. Nystagmus is frequently present but is not specific for Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

The oculomotor palsies, if acute, may respond dramatically to intravenous thiamine with resolution immediately after the vitamin is administered. If the deficit has been present for a long time the response is less impressive or totally absent.

The oculomotor palsies, if acute, may respond dramatically to intravenous thiamine with resolution immediately after the vitamin is administered. If the deficit has been present for a long time the response is less impressive or totally absent.

Ataxia in Wernicke’s encephalopathy affects principally the gait and is due to a combination of peripheral neuropathy and degenerative changes in the vermis of the cerebellum.

Ataxia in Wernicke’s encephalopathy affects principally the gait and is due to a combination of peripheral neuropathy and degenerative changes in the vermis of the cerebellum.

Confusion, disorientation, and inattention are common signs of the mental changes in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. The classic manifestation is the Korsakoff’s syndrome.

Confusion, disorientation, and inattention are common signs of the mental changes in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. The classic manifestation is the Korsakoff’s syndrome.

Korsakoff’s syndrome, also known as amnestic-confabulatory syndrome, is classically associated with Wernicke’s, but may occur independently in chronic alcoholics.

Korsakoff’s syndrome, also known as amnestic-confabulatory syndrome, is classically associated with Wernicke’s, but may occur independently in chronic alcoholics.

The striking feature of Korsakoff’s syndrome is amnesia for recent or current events with relative preservation of long-term memory. Classically, the patient with Korsakoff’s syndrome fills in (confabulates) the amnestic deficits with made-up stories that can be elicited by the examiner (e.g., “how did you like the party last night?” which the patient responds to with elaborate made-up—confabulated—details).

Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration occurs in chronic alcoholics and principally affects the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar vermis.

Alcoholic cerebellar degeneration occurs in chronic alcoholics and principally affects the Purkinje cells of the cerebellar vermis.

Lower extremity findings are more pronounced than upper extremity abnormalities and speech disorders although the latter may occur in severe cases.

Alcohol-related dementia also occurs in association with diffuse cerebral atrophy.

Alcohol-related dementia also occurs in association with diffuse cerebral atrophy.

The relationship to the Korsakoff’s syndrome is uncertain but more generalized dementia occurs in some chronic alcoholics.

ALCOHOL WITHDRAWAL SYNDROMES

Alcohol is a potent CNS depressant. Adaptation to the depressed cerebral state results in a variety of excitatory changes when the depressive effect is abruptly removed by a decrease in alcohol intake. Sustained heavy drinking for a long time is necessary before pronounced withdrawal manifestations appear. Sympathoadrenal excitation is an important concomitant of severe alcohol withdrawal. There are three generally recognized and distinct withdrawal syndromes: seizures, alcoholic hallucinosis, and delirium tremens (DTs).

An alcohol withdrawal seizure usually occurs about 1 or 2 days after the last drink. The withdrawal seizure is typically generalized and single, although rarely, a brief burst of a few seizures may occur.

An alcohol withdrawal seizure usually occurs about 1 or 2 days after the last drink. The withdrawal seizure is typically generalized and single, although rarely, a brief burst of a few seizures may occur.

More than one seizure should raise the suspicion of a cause other than, or in addition to, alcohol withdrawal. Treatment with typical anticonvulsants is not indicated for simple withdrawal seizures although benzodiazepines are generally given and may prevent the development of more severe withdrawal. Chronic antiseizure medication is not recommended for the prophylaxis of withdrawal seizures. An alcoholic on chronic anticonvulsive therapy is prone to withdraw from both the medication and alcohol; the result may then be status epilepticus rather than a single seizure.

Alcoholic hallucinosis begins 1 to 2 days after the last drink. The hallucinations are not frightening and not accompanied by signs of marked autonomic stimulation.

Alcoholic hallucinosis begins 1 to 2 days after the last drink. The hallucinations are not frightening and not accompanied by signs of marked autonomic stimulation.

This is the typical “pink elephant” hallucination. These last for 1 to 2 days.

DTs typically begins 3 to 5 days after the last drink and may last as long as a week. Frightening hallucinations, disorientation, sympathetic stimulation with tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis dominate the clinical course.

DTs typically begins 3 to 5 days after the last drink and may last as long as a week. Frightening hallucinations, disorientation, sympathetic stimulation with tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, and diaphoresis dominate the clinical course.

The hallucinations in DTs frequently involve images of fire.

The hallucinations in DTs frequently involve images of fire.

DTs are serious and may be fatal if not treated appropriately. Benzodiazepines are the agents of choice but care to avoid oversedation is critical.

ALCOHOL AND THE HEART

The relationship between alcohol intake and heart disease is complex since it follows a “J” shaped curve: modest intake (approximately one or two drinks per day) is associated with decreased coronary artery disease and decreased all-cause mortality, while intake in excess of two or three drinks per day is associated with decreased survival. Four to five drinks per day is associated with an increase in hypertension, and serious alcoholics are at risk for alcoholic cardiomyopathy.

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy occurs in long-standing heavy drinkers and reflects the direct toxic effects of alcohol as well as the impact of nutritional deficiencies particularly the lack of thiamine.

Alcoholic cardiomyopathy occurs in long-standing heavy drinkers and reflects the direct toxic effects of alcohol as well as the impact of nutritional deficiencies particularly the lack of thiamine.

The “wet” form of beriberi is a dilated cardiomyopathy with peripheral vasodilation and high output failure. Thiamine deficiency may contribute to the dilated cardiomyopathy that occurs in chronic alcoholics, but alcohol-induced hypertension is also a factor as is the direct toxic effect of excessive alcohol intake.

The clinical presentation of alcoholic cardiomyopathy is usually dominated by signs of right heart failure; anasarca is not unusual and bilateral pleural effusions and ascites may be present.

The clinical presentation of alcoholic cardiomyopathy is usually dominated by signs of right heart failure; anasarca is not unusual and bilateral pleural effusions and ascites may be present.

The presence of Laennec’s cirrhosis may complicate the clinical picture with ascites and edema.

All alcoholics presenting with heart failure should receive intravenous thiamine as part of the therapeutic regimen.

All alcoholics presenting with heart failure should receive intravenous thiamine as part of the therapeutic regimen.

Rhythm disturbances, particularly, atrial tachycardias and atrial fibrillation are also common in patients with alcoholic cardiomyopathy.

Rhythm disturbances, particularly, atrial tachycardias and atrial fibrillation are also common in patients with alcoholic cardiomyopathy.

The term “holiday heart” refers to arrhythmias occurring after binge drinking in patients who are not necessarily chronic alcoholics.

The term “holiday heart” refers to arrhythmias occurring after binge drinking in patients who are not necessarily chronic alcoholics.

Atrial fibrillation and other supraventricular tachycardias subside after the alcohol wears off.

HEMATOLOGIC CONSEQUENCES OF ALCOHOLISM

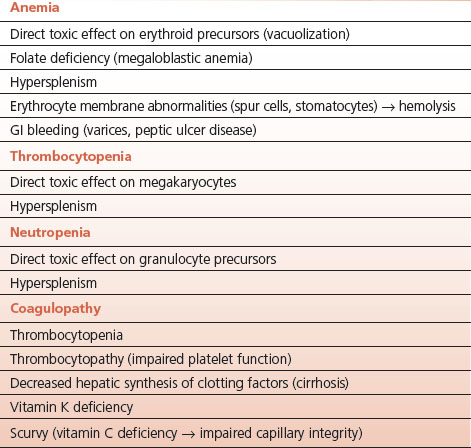

Chronic alcoholism affects all three hematologic cell lines with resultant anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia (Table 15-1). The mechanisms involved are manifold and involve direct effects of alcohol, nutritional deficiencies, concurrent Laennec’s cirrhosis, and hypersplenism.

Hypersplenism, a consequence of portal hypertension in Laennec’s cirrhosis, affects all of the three cell lines singly or in any combination.

Hypersplenism, a consequence of portal hypertension in Laennec’s cirrhosis, affects all of the three cell lines singly or in any combination.

TABLE 15.1 Hematological Consequences of Alcoholism and Laennec’s Cirrhosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree