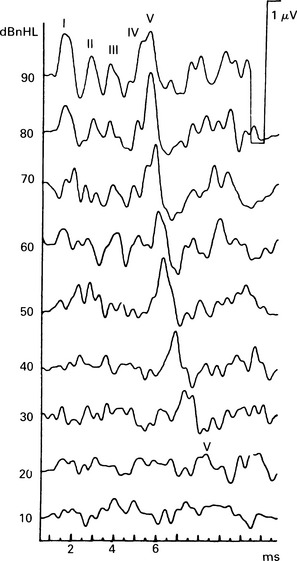

11 In order to apply the numerous ERA techniques appropriately, it is important to know their comparative merits in particular clinical situations. The clinical factors include, for example, how evoked-response threshold techniques may be affected by the age and state of the patient, the need for general anaesthesia, the possible site of the lesion, and the accuracy needed for practical purposes. Auditory-evoked potentials are the averages from ongoing bio-electrical activity and ambient electrical noise. The signal-to-noise ratio is one of the most important factors for good-quality recordings, and it is up to the tester to decide the intensity of the stimuli, number of sweeps, number of replications, artefact rejection limits, and other technical recording factors, although some laboratory systems continue averaging until a certain S/N ratio is attained. Both physiologic and non-physiologic electrical noise can have an effect on test duration, threshold sensitivity, and threshold variability. Nevertheless, even in non-ideal conditions, an adequate response may be obtained (Fig. 11.1). Fig. 11.1 ABR threshold estimation in a child. The recordings were made in an electrically unscreened operating theatre. Whilst the traces are ‘noisy’, the prominent wave V can, nevertheless, be detected and the threshold estimate made. Electrical interference can considerably reduce the quality of the recording. It may be a problem when the tests are carried out in neonatal units or operating theatres. All non-essential electrical equipment, especially fluorescent lights, should be switched off. Interpretation of the SVR may be more difficult, as there may be myogenic artefacts, as well as contamination by prominent alpha and theta rhythmical activity on the EEC The subject’s eyes should be open in order to reduce alpha rhythm. The SVR is known to be a stimulus-orientated response, and is usually recorded easily in a patient who anticipates the stimulus. Natural sleep and general anaesthesia have an effect on both EEG and SVR, making identification of the response at the threshold more difficult. Natural sleep after a feed is an ideal condition for testing neonates with ABR and MLR. In older infants, sedation may be required, which can be administered orally or per rectum. For children who are difficult to test, including those that are hyperactive or have brain damage, mental handicap, or behavioural problems, sedation may not be adequate, and they may need light general anaesthesia in order to achieve good recording conditions. It is unnecessary to use muscle relaxants, although they can improve the recordings further. Some clinics have reported that transtympanic ECochG in adults may cause momentary discomfort when placing the electrode, but most patients tolerate transtympanic needle ECochG well, even without local anaesthesia. Local anaesthetic sprays and iontophoresis have been used to anaesthetize the tympanic membrane, but their effectiveness is variable. The risks associated with ERA should be considered. Complications may occur if general anaesthesia is used, and those compromising the laryngeal airway in children are serious. (Crowley et al 1976) reported that 3 out of 603 patients known to have had general anaesthesia experienced laryngospasm. ECochG results from different centres have been assessed in 2256 patients, of whom 13 who had local or general anaesthesia experienced nausea, vomiting, and vertigo. Acute otitis media was reported in 2 out of 1875 patients following transtympanic ECochG, which is a risk of about 0.1% (Crowley et al 1976). Out of more than 3000 transtympanic ECochG reported by Gibson et al (1983), 1 patient complained that his trigeminal neuralgia was worse for 2 months following the test, and another patient complained that his tinnitus had become louder.

Comparative assessment of ERA threshold techniques

IDENTIFICATION OF THE RESPONSE

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS OF THE PROCEDURE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree