Diagnostic Testing

- When esophageal dysphagia is suspected, endoscopy is the initial test to visualize the mucosa directly with biopsy of suspicious lesions and/or biopsy of the midesophagus for eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Barium swallow can be used to identify structural defects in patients at high risk for sedation and those taking anticoagulants.

- Modified barium swallow is used to evaluate oropharyngeal dysmotility and aspiration.

- Laryngoscopy can identify oropharyngeal lesions.

- Esophageal manometry is the test of choice when esophageal motor disease is suspected.

TREATMENT

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be treated with proton pump inhibitors.4

- Esophageal strictures or rings can be treated with endoscopy by bougienage (the passage of dilators with or without guidewire assistance) or balloon dilators.

- Achalasia can be treated with the following:

- Pneumatic dilatation via fluoroscopic and endoscopic visualization.

- Heller myotomy (surgical procedure that dissects the smooth muscle of the hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter).

- Botulinum toxin injection can be used for those at high risk for other interventions. The effects of botulinum toxin injection are temporary, usually lasting 3 to 6 months.

- Pneumatic dilatation via fluoroscopic and endoscopic visualization.

- Eosinophilic esophagitis can be treated with aggressive acid suppression, elimination diets, and/or swallowed fluticasone.

- Odynophagia may be treated symptomatically with opioid analgesic agents or topical viscous lidocaine.

- Pill ulcers are generally self-limited.

- Infectious causes of odynophagia should be treated with appropriate antimicrobials.

- Pill ulcers are generally self-limited.

Nausea and Vomiting

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- The initial evaluation should determine the duration and severity of symptoms.

- Association with certain triggers including smells, tastes, emotional or physical stress, headaches, and abdominal pain should be noted.

- If abdominal pain is the main symptom, refer to the Abdominal Pain section of this chapter for the differential diagnosis.

- Nausea and/or vomiting associated with right upper quadrant (RUQ) or epigastric pain could be secondary to biliary colic, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, peptic ulcer disease, or acute viral hepatitis.

- Initial periumbilical pain that relocates to the right lower quadrant accompanied by nausea and vomiting is suggestive of appendicitis.

- Left lower quadrant pain in the presence of vomiting may be secondary to diverticulitis.

- Flank pain along with fever and vomiting may indicate pyelonephritis.

- Occurrence soon after meals can be a result of gastric outlet obstruction.

- Vomiting that is delayed after meals and consists of partially digested food or food consumed several hours earlier may indicate gastroparesis (particularly in diabetics) or intestinal obstruction.

- Vomiting undigested food (regurgitation) is seen with a Zenker diverticulum (pharyngoesophageal diverticulum) and achalasia, which are also associated with severe halitosis.

- Presence of diarrhea may indicate an infectious gastroenteritis.

Physical Examination

- Evaluate for orthostatic hypotension defined by fall of systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or 10 mm Hg diastolic with positional change, which may be present in persistent vomiting due to volume depletion.

- Decreased skin turgor or dry mucous membranes are signs of significant fluid losses.

- Severe halitosis may be associated with intestinal obstruction, gastroparesis, gastrocolic fistula, bacterial overgrowth, achalasia, and Zenker diverticulum.

- Oral examination may reveal poor dentition and enamel erosion in those with eating disorders such as bulimia.

- High-pitched bowel sounds may suggest small bowel obstruction, while succussion splash (the movement of gastric fluid within the stomach heard on auscultation) may be seen in gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis.

- Palpation to find areas of tenderness, abdominal masses, or Murphy sign.

Differential Diagnosis

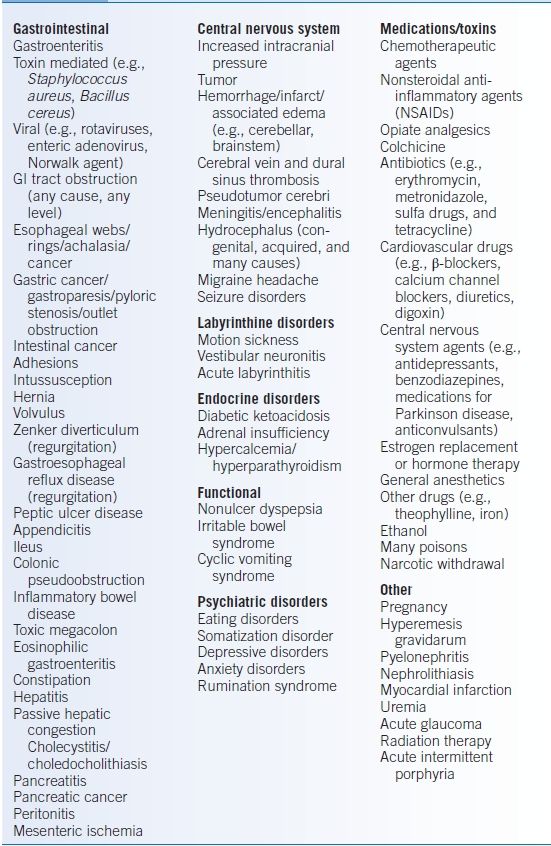

The differential diagnosis of nausea and vomiting is presented in Table 28-2.

TABLE 28-2 Causes of Nausea and Vomiting

Data from Quigley EM, Hasler WL, Parkman HP. AGA technical review on nausea and vomiting. Gastroenterology 2001;120:263–286.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- Serum chemistries evaluating electrolytes, bilirubin, amylase, lipase, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases. Hyponatremia and azotemia may cause nausea and vomiting. Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia can be seen in adrenal insufficiency. Check AM cortisol if adrenal insufficiency is suspected.

- Complete blood cell count (CBC) evaluating for leukocytosis indicating acute inflammation or infection as well as anemia indicating possible blood loss within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

- Pregnancy test should be obtained in women of childbearing age.

Imaging

- If nausea and vomiting are associated with pain, an obstructive series is important to identify intestinal obstruction, air-fluid levels, bowel gas pattern, and free air.

- Upper GI endoscopy can detect mechanical sources of nausea and vomiting. If negative, a small bowel exam should be considered, such as small bowel follow-through, capsule endoscopy, or CT enterography.

- Radionuclide gastric-emptying scan and manometry can evaluate for motility disorders of the stomach.

- CT may be obtained to evaluate for intra-abdominal processes, such as pancreatitis or appendicitis.

- CT scan or MRI of the brain may be pertinent if an intracranial process is suspected.

TREATMENT

- Identify and treat underlying process, using antiemetic agents to temporarily alleviate symptoms.

- Prochlorperazine starting at 5 to 10 mg PO tid/qid or 25-mg suppositories every 12 hours.

- Promethazine starting at 12.5 to 25 mg PO every 4 to 6 hours or 25-mg suppositories every 4 to 6 hours.

- Also, refer to Chapter 36 for a more detailed discussion of antiemetic therapy.

- Prochlorperazine starting at 5 to 10 mg PO tid/qid or 25-mg suppositories every 12 hours.

- Prokinetic medication such as metoclopramide may be used for delayed gastric emptying; the starting dose is 10 mg PO/IM/IV 1 hour before meals and at bedtime.

- Mechanical obstruction must be excluded before using prokinetics.

- Metoclopramide should not be used for prolonged periods and/or in high doses, particularly in the elderly, because of the risk of drug-induced tardive dyskinesia.

- Mechanical obstruction must be excluded before using prokinetics.

- A number of serotonin receptor inhibitors, such as ondansetron, or antagonists of substance P/neurokinin-1 receptors, such as aprepitant, are frequently used in nausea and emesis related to chemotherapy.

- Indications for hospitalization:

- Clinical evidence of severe volume depletion

- Electrolyte derangements that require correction under monitored conditions

- Patients at extremes of age and those with diabetes and/or accompanying debilitating illnesses

- Clinical evidence of severe volume depletion

Dyspepsia

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Persistent or recurrent discomfort or pain located in the upper abdomen. Pain can be accompanied by bloating, heartburn, nausea, and food intolerance.

- Divided into two categories: peptic ulcer disease and nonulcer dyspepsia.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Pain in the preprandial state or nocturnal pain that results in awakening several hours after ingestion of food is suspicious for peptic ulcer disease. Similar pain that is relieved by food is suggestive of a duodenal ulcer.

- Pain from nonulcer dyspepsia is difficult to distinguish from ulcer-related dyspepsia.

- Pain radiating to the back and somewhat improved on leaning forward suggests pancreatitis, perforated peptic ulcer, or leaking abdominal aneurysm.

- Pain referred to the right scapula may originate in the gallbladder or from any process causing diaphragmatic irritation.

- Constipation, diarrhea, tenesmus, or nonspecific lower abdominal discomfort in association with upper abdominal complaints may be due to irritable bowel syndrome.

- Early satiety can result from ulcers at the gastric outlet or infiltrating tumors creating reduced gastric wall compliance.

- Fear of eating because of subsequent abdominal pain is suggestive of mesenteric ischemia or intestinal angina.

- History of peptic ulcer disease, gastric surgery, cigarette smoking, or alcohol use are risk factors for the development of dyspepsia.

- Early satiety, recurrent vomiting, or bloating that is not accompanied by visible distention or pain may indicate dysmotility.

- Aerophagia is excess swallowing of air that results in fullness, belching, or reflux-like symptoms relieved by repetitive belching. Aerophagia is usually psychiatric in origin.

- Red flags: weight loss, GI bleeding, recurrent vomiting, dysphagia, and NSAID use.

Physical Examination

- Abdominal tenderness to palpation is nonspecific and may be seen in most disorders that cause dyspepsia. RUQ tenderness increased by palpation with inspiration (Murphy sign) indicates cholecystitis.

- Evaluate for peritoneal signs such as guarding and rebound tenderness (i.e., discomfort induced by movement of an irritated peritoneum during the release of pressure from palpation).

- Jaundice suggests a hepatic or biliary process.

- Evaluate for blood in stool.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

CBC looking for anemia, if GI bleeding is suspected, and leukocytosis indicating possible intra-abdominal infection.

Diagnostic Procedures

- Endoscopy of the upper GI tract is indicated for those with alarm symptoms, for new-onset dyspepsia in a patient over 50, and for whom trials of acid-suppressing medications are inadequate.5

- Helicobacter pylori testing is appropriate if mucosal abnormalities, such as peptic ulcers, erosive gastropathy, or duodenitis, are detected, or in the case of documented prior peptic ulcer disease and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

- Upper GI barium radiographs are reserved for patients who cannot undergo endoscopy.

- Gastroparesis can be demonstrated by gastric-emptying scintigraphy but must be interpreted in conjunction with the clinical setting.

- Transabdominal ultrasound can be used to evaluate for liver and biliary tract abnormalities.

TREATMENT

- Peptic ulcer disease should be managed with acid suppression. Documentation of healing is recommended for gastric ulcer.6 Helicobacter pylori should be tested for and eradicated if found.

- Nonulcer dyspepsia may not respond to specific treatment but may improve with acid suppression or neuromodulators such as tricyclic antidepressants. In those with alarm symptoms or new-onset dyspepsia after age 50, upper endoscopy is warranted.7

- Reflux should be treated symptomatically with regularly scheduled proton pump inhibitors as well as weight reduction, dietary changes, and elevation of the head of bed.4

- Dysmotility-like dyspepsia may benefit from prokinetic agents such as metoclopramide. Metoclopramide should not be used for prolonged periods and/or in high doses, particularly in the elderly, because of the risk of drug-induced tardive dyskinesia.

Abdominal Pain

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

One of the most valuable diagnostic tools in evaluating the patient with abdominal pain is the history. The location and features of pain are useful in narrowing the differential diagnosis to an organ (e.g., hepatobiliary, gastric, and intestinal) as well as to a cause (e.g., inflammation, infection, obstruction, ischemia, and neurogenic).

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

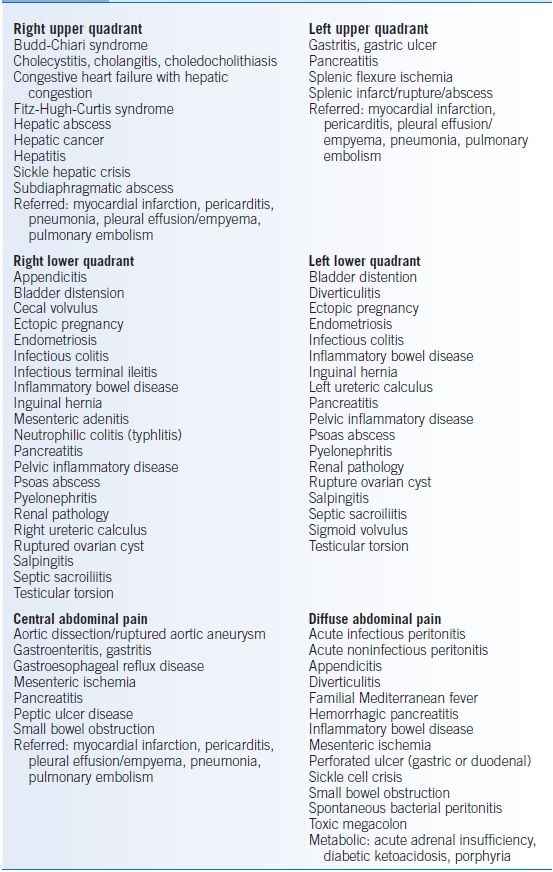

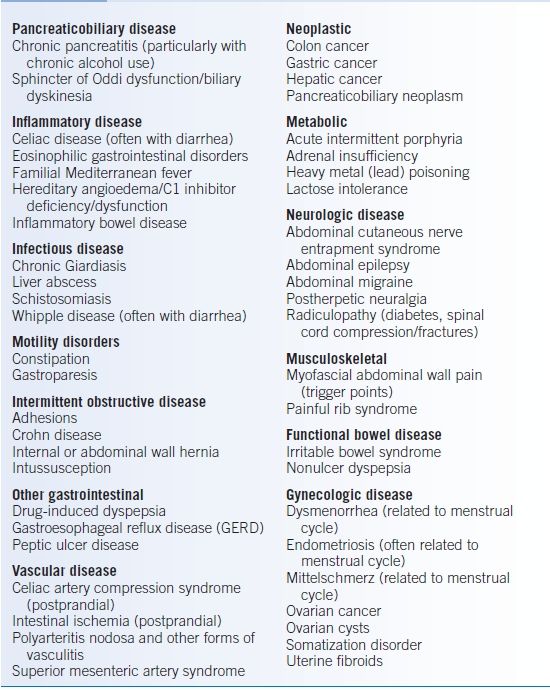

- The initial evaluation should focus on the chronology of events and determine the duration of symptoms (e.g., acute [Table 28-3] or chronic [Table 28-4]).

- The first consideration for a patient with acute abdominal pain is whether they can be evaluated in an outpatient setting or whether an emergency room is more appropriate.

- Some causes of abdominal pain can be well localized, particularly if they result from inflammation in the parietal peritoneum (Table 28-3).

- Substernal chest pressure or pain can be indicative of esophageal disorders. This can result in pain that radiates to the neck, jaw, arms, and back and may mimic cardiac angina.

- Epigastric discomfort may be secondary to a process affecting the stomach, duodenum, and pancreas, while stretching of the liver capsule or gallbladder distention or inflammation can result in RUQ pain. Small bowel obstruction and appendicitis may localize to the periumbilical area. Colonic pain may be localized to the lower abdomen but can be generalized. Abdominal disease causing inflammation under the diaphragm can produce referred pain in the shoulder.

- Non-GI abdominal pain can result from the following:

- Urinary tract disease (e.g., cystitis, pyelonephritis, obstructive uropathy, and nephrolithiasis) is often associated with dysuria or hematuria and can cause pain in the flanks or suprapubic area as well as abdominal discomfort.

- Pleural, pulmonary, or pericardial etiologies may cause upper abdominal pain.

- Gynecologic etiologies must be considered in women with lower abdominal symptoms (Tables 28-3 and 28-4).

- Urinary tract disease (e.g., cystitis, pyelonephritis, obstructive uropathy, and nephrolithiasis) is often associated with dysuria or hematuria and can cause pain in the flanks or suprapubic area as well as abdominal discomfort.

- Description of pain that is sharp, tearing, and cutting may indicate an acute process, whereas descriptors such as gnawing, burning, dull, or boring point toward a chronic process.

- Colic describes pain with a waxing and waning intensity.

- Certain movements can generate abdominal pain due to musculoskeletal disorders or nerve root compression.

- Pain that is worse while supine may indicate pancreatic disease.

- Postprandial pain may indicate a process such as cholecystitis, pancreatitis, bowel obstruction, or gastric ulcer. In contrast, pain from duodenal ulcers generally improves with food ingestion. Intestinal angina may be associated with a fear of eating due to pain and result in weight loss.

- Nausea and emesis are nonspecific symptoms and can occur in association with abdominal pain due to a number of causes. Diarrhea associated with nausea and emesis suggests an infectious source.Hiccups can result from distention of the esophagus or stomach or irritation of the diaphragm.

- Patients should be questioned about changes in bowel movements, stool caliber, and stool volume. Constipation can result in diffuse abdominal discomfort, while diarrhea can be accompanied by cramping. Patients with alternating complaints of diarrhea and constipation may have irritable bowel syndrome.

- GI bleeding raises concern for ulcers, infections, inflammation, or ischemia. Melena (dark, tarry stool) usually signals an upper GI source, although it can occur during right-sided colonic bleeding or small bowel bleeding. Hematochezia (bright red blood from the rectum) usually reflects a colonic source but sometimes presents during massive upper bleeding.

- Menstrual cycles, irregularity, or abnormalities in bleeding may cause abdominal pain or worsening of underlying GI disorders. Symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome can clearly worsen during and around the time of menses. Pain that follows a close pattern of menstrual cycles may be due to underlying endometriosis.

- Psychiatric causes should be considered in patients with underlying depression and anxiety, after organic causes are eliminated.

- Red flags: pain that awakens the patient from sleep, fever, prolonged severe pain of more than several hours duration, persistent vomiting, changes in patterns or location, significant alterations in appetite or mental status, unintentional weight loss, and GI bleeding.

TABLE 28-3 Common Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain by Location

Data from Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, et al. Textbook of Gastroenterology, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Physical Examination

- Inspection and assessment for signs of systemic illness such as cachexia, pallor, severity of distress, presence of ascites, masses, prior surgical procedures, or other abnormalities, and presence of cutaneous findings of underlying cirrhosis.

- Auscultation for presence or absence of bowel sounds. High-pitched sounds may indicate bowel obstruction, whereas absence of sounds may be a feature of ileus or peritonitis.

- Tympanic percussion can indicate gas-filled or dilated loops of bowel. Dullness may indicate a mass or ascites, particularly if percussed in the flanks. Dullness below the left costal margin may indicate splenomegaly, and dullness below the right costal margin may indicate hepatomegaly.

- Palpation for the detection of hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. Palpation for masses, localized tenderness, or ascites. Murphy sign is tenderness to palpation in the RUQ, which induces a midinspiratory pause in breathing, and is suggestive of cholecystitis.

- Mesenteric ischemia classically presents with pain that is out of proportion to findings on physical examination.

- Signs worrisome for surgical abdomen include guarding and peritoneal signs (rebound tenderness or a rigid abdomen), fever, Murphy sign, iliopsoas sign (hyperextension of right hip causing abdominal pain associated with appendicitis or terminal ileal disease, absent or high-pitched bowel sounds.)

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- CBC, looking for the following: leukocytosis suggesting acute inflammatory response; anemia, which can indicate GI bleeding; and thrombocytopenia suggesting liver disease.

- Serum chemistries evaluating electrolytes, bilirubin, amylase, lipase, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases

- Urinalysis to assess hydration, proteinuria, infection, and renal disease

Imaging

- Plain films (obstructive series) are easy, inexpensive, and low risk. They can detect obstruction or perforation (free air under the diaphragm). However, when there is no real concern for obstruction or perforation, plain films are rarely diagnostic.

- Ultrasound to evaluate for organomegaly, masses, ascites, or biliary tract disease.

- CT scan may be more sensitive in detecting intra-abdominal processes.

TABLE 28-4 Causes of Chronic Abdominal Pain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree