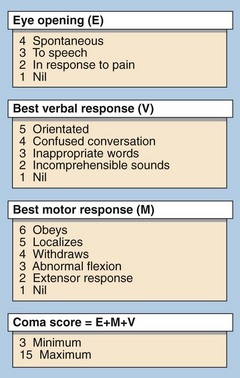

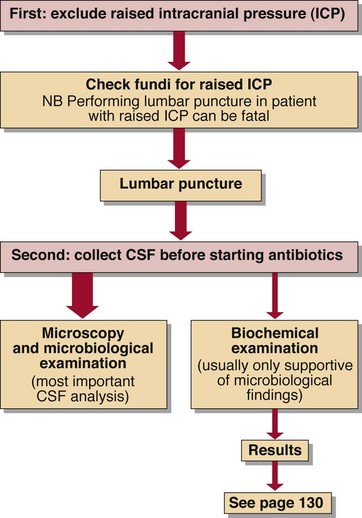

63 The depth of coma can be defined following clinical examination using a scale such as that in Figure 63.1. This allows clinical staff to establish the severity of the coma and to monitor changes. Obtaining the correct diagnosis is paramount. To this end the most valuable information is usually obtained from the clinical history, but frequently a reliable history is not available. A helpful mnemonic in the diagnosis of the unconscious patient is given in Figure 63.2. However, within each of these categories described there are many possible causes. The first priorities in treating an unconscious patient are to ensure that airways are clear and that breathing and circulation are satisfactory. Where coma of cerebrovascular origin is suspected a CSF examination may show the presence of blood and will help to differentiate a subarachnoid haemorrhage from cerebral infarction (see p. 130). When available, imaging with a CT scan or MRI is preferable. Meningitis (bacterial and viral) and encephalitis (viral) can both lead to coma. Meningococcal meningitis has a high mortality, especially in children. Diagnosis is of great importance and CSF specimens should be obtained before antibiotic therapy is commenced (Fig 63.3). The usual findings are:

Coma

Differential diagnosis of coma

Cerebrovascular accident

Infectious causes

Coma