12 1. Colonoscopy has revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of colonic disease, allowing accurate mucosal visualization, biopsy and therapeutic polypectomy. Technological advances in instrumentation allow rapid and safe examination of the whole colon, provided the endoscopist has been adequately trained in the technique. 2. Use diagnostic colonoscopy to evaluate an abnormal or equivocal barium enema or CT cologram, particularly where diverticular disease or colonic spasm may often obscure a small mucosal lesion. Colonoscopy should be the first-line investigation for unexplained rectal bleeding or iron deficiency anaemia and is the investigation of choice for all patients with a positive faecal occult blood test. Colonoscopy is the most accurate diagnostic tool for differential diagnosis and assessment of extent in inflammatory bowel disease, but should be avoided in acute disease, where technetium-labelled white cell scanning, if available, is a safer alternative. 3. Therapeutic colonoscopy has changed the management of colorectal polyps, facilitating removal of all pedunculated and most sessile adenomatous lesions, particularly with the advent of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), thus providing an opportunity for colorectal cancer prevention. Diathermy coagulation or laser therapy of vascular abnormalities such as angiodysplasia may pre-empt laparotomy in acute colonic haemorrhage or cure anaemia due to chronic blood loss. 4. Relief of obstruction in colorectal cancer, either as an initial procedure prior to surgical resection or as long-term palliation, may be achieved using either laser vaporization or stent insertion. 5. Perform surveillance colonoscopy with chromoscopy and biopsy of abnormal areas of mucosa in all individuals with a 10 year history of ulcerative or Crohn’s colitis. Further surveillance should be according to current BSG or NICE guidelines, which outline high-risk factors for dysplasia, concomitant family history and primary biliary cirrhosis with recommended intervals between surveillance colonoscopies. Surgery is indicated only in those with definite dysplasia or carcinoma, thus avoiding colectomy in over 80% of cases. 6. Following polypectomy or curative resection for colorectal cancer, carry out regular follow-up colonoscopy, according to the risk factors as outlined in the current BSG guidelines. 7. Commence screening of patients with familial polyposis coli from age 15 years (if gene-positive) and continue approximately 2-yearly until the age of 40 years. Hereditary non-polyposis coli families should undergo 1–2-yearly surveillance, commencing at least 10 years younger than the index case. If facilities exist, then screen subjects with a strong family history of colorectal cancer (i.e. one first-degree relative with onset before 40 years of age, or more than one first-degree relative of any age) in the hope of reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer by removing adenomatous lesions. 8. Emergency colonoscopy is rarely helpful in cases of acute, severe rectal bleeding. Anorectal and upper gastrointestinal causes should be excluded by rigid proctosigmoidoscopy and gastroscopy. Bleeding usually ceases in up to 90% of patients, allowing colonoscopy within 4 to 6 weeks after bowel preparation. In those cases where haemorrhage continues, angiography with embolization of a bleeding point may be helpful. However, if a diagnosis has not been reached and emergency laparotomy becomes necessary, you may perform colonoscopy under general anaesthetic with the peritoneal cavity exposed, following on-table lavage with saline or water introduced via a Foley catheter through a caecostomy. 1. Accurate, rapid examination depends upon effective bowel preparation. Advise patients to discontinue any iron preparation or stool-bulking agents 1 week prior to endoscopy and change to a low-residue diet for at least 2 days. Twenty-four hours before examination restrict oral intake to clear fluids such as coffee or tea without milk, concentrated meat extract and glucose drinks. Give a purgative such as sodium picosulphate or ‘low volume’ polyethylene glycol preparation 12–18 hours before colonoscopy and repeat it 4 to 6 hours before examination. Alternatively, give ‘high volume’ balanced electrolyte solution combined with polyethylene glycol, which have been shown to produce rapid preparation without the need for dietary restriction. Administration of metoclopramide 10 mg prior to ingestion of the 3–4 L of solution enhances gastric emptying and reduces nausea and vomiting. 2. Written, informed consent for the procedure should be obtained from all patients prior to bowel preparation and arrival for the procedure. The nature, purpose and risks of the procedure, together with alternatives, should be explained, including the implications of sedation. Give reassurance about the examination to allay fears, allowing minimal levels of sedation to be used. 3. Colonoscopy is usually performed under intravenous sedation with the addition of an analgesic. Do not give excessive sedation or analgesia as this may result in circulatory or respiratory depression. Additionally, it will dull appreciation of severe pain which should occur only when a poor technique is used, causing dangerous overstretching of the bowel. For similar reasons do not perform colonoscopy under general anaesthesia, apart from as an intra-operative procedure in cases of acute colonic haemorrhage. Elderly patients in particular can suffer significant hypotension following pethidine, and this, combined with the synergistic effect of opiates and benzodiazepines, can also cause significant falls in oxygen saturation. In order to avoid these complications, use only small doses of analgesic and hypnotic such as intravenous pethidine 25 mg or fentanyl 50 ug plus midazolam 2–3 mg. Monitor all patients by pulse oximetry, during and after the procedure, and give added inspired oxygen in all cases. Always have available antidotes to benzodiazepines (flumazenil) and opiates (naloxone), together with full cardiorespiratory resuscitation equipment and staff trained to use it in case of emergency. Occasionally an antispasmodic, either intravenous hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) or intraluminal peppermint oil suspension may be employed. 4. As a rule, commence examination of the patient in the left lateral position or, alternatively, supine. Use a tipping trolley in case of cardiorespiratory problems. Have available at least two trained assistants: one to observe the patient’s vital signs and the other to assist with the accessories for biopsy or snare polypectomy. 5. Check all equipment prior to intubation. The colonoscope must have been adequately cleaned and disinfected. The light source, endoscope angulation controls, air/CO2 insufflation, lens washing and suction facilities must be in full working order. If using a variable stiffness colonoscope ensure that the dial is at ‘0’. Check the diathermy equipment for correct, safe operation. Ensure that all accessories, such as biopsy forceps polypectomy snares and injection needles, are available in the room. 1. Modern colonoscopes are sophisticated precision instruments designed to enhance intubation of the colon in the most efficient manner. As well as a wide-angled lens to allow a greater field of vision and high definition video chip camera, graduated torque characteristics assist variability in the stiffness of the instrument. In addition, some colonoscopes have an ability to vary the stiffness of the insertion shaft. 2. During intubation, the instrument may be pushed forward or pulled back. Change of direction may be achieved by angulation of the distal end, up/down or left/right. Change of direction may also be achieved by up/down deflection, combined with rotation or torque. Keeping the distal section of the instrument as straight as possible and restoring this to a neutral position as soon as possible after angulation around an acute bend helps to prevent loop formation. Avoid maximum up/down and left/right angulation, as this results in a J-shape and rotation of the end of the instrument rather than change of direction. Advancement may also be achieved by the straightening of a loop using torque and withdrawal or by suction, causing a concertina effect of the bowel over the endoscope. 3. Colonoscopy is made easier if the anatomy of the colon is properly understood. The rectum is fixed in a retroperitoneal position and consists of alternating mucosal folds forming the valves of Houston. The sigmoid colon is freely mobile on its mesentery and of variable length and configuration. The descending colon and splenic flexure are relatively fixed by their peritoneal attachments. At the splenic flexure, the direction of the colon is forwards and downwards to the transverse colon which, like the sigmoid, is of variable length and freely mobile on the transverse mesocolon. The bowel becomes fixed again at the hepatic flexure and the direction passes forwards and downwards into the ascending colon and caecum, which are usually fixed by peritoneal attachments, though less consistently than the descending colon. It is the mobile and variable-length sigmoid and transverse colon that cause the most difficulty through looping of the instrument. 4. The aim of colonoscopy is to achieve intubation from the anus to caecum with the minimum possible length of instrument. Characteristically, the colonoscope, when straight and without loop formation, should be in a roughly U-shaped configuration with 70–80 cm of instrument inserted to the caecal pole (Fig. 12.1). Significantly greater insertion length indicates the presence of a loop.

Colonoscopy

DESCRIPTION OF OPERATION

Appraise

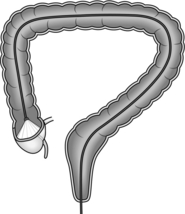

Prepare

Access