OVERVIEW

- CBT can be effective for a wide range of functional symptoms

- Cognitive approaches do not aim to uncover the cause, they address perpetuating factors for symptoms

- CBT is not about ‘thinking yourself better’, rather it looks for logical, but counterproductive thoughts that may be acting as obstacles to a natural recovery

This chapter and the one that follows describe the CBT approach to medically unexplained symptoms (MUS). CBT, when delivered by specialist therapists, has been shown to be effective for many of the individual MUS syndromes and for patients with complex and multiple symptoms. A popular conception of CBT is that it is essentially a kind of positive thinking. On the contrary, CBT is about realistic, objective thinking, using reason and reality to test out beliefs.

The aim of these chapters is not to turn GPs or other generalists into CBT practitioners. Rather they aim to show how a CBT model of MUS looks in order that (a) generalists using some of the techniques in other chapters will see their parallels or origins in CBT and (b) generalists considering referring patients for CBT understand more of the treatment aims and processes.

CBT—‘it’s NOT all in your mind’

When it comes to MUS, medicine and psychiatry still tend to fall back on the Freudian default. The psychoanalytic assumption is that MUS are messages from the unconscious: the person is distressed and unaware of it, but that distress will out, if necessary as physical symptoms.

People with MUS often come to CBT expecting this interpretation of their symptoms. Instead CBT seeks to build an alternative model of the condition, one in which the word psychological rarely figures. This chapter looks at CBT models, and then at some of the more common specific cognitive strategies. These should be considered in conjunction with the behavioural strategies in the next chapter.

CBT is not particularly concerned with making a diagnosis, or of considering anything—even anxiety or depression—as purely psychological problems. Rather, a CBT therapist seeks to understand the particular interactions of body and mind—of thoughts, feelings, behaviour and physical symptoms—that an individual is experiencing, and how those interactions maintain their distress. In short, CBT is interested in a problem formulation, not diagnosis. Let us see how this works in practice in MUS.

‘David’ is a 37-year-old lecturer in law, with a 1-year history of unexplained fatigue, hoarseness and loss of voice. As a result of these symptoms, he has had a lot of sick time over the past year. He is currently on summer holidays, but dreading returning to work. He has always been prone to worry and low mood, and describes himself as real perfectionist who pushes himself hard.

The current problem started about a year and a half ago, when he took up a new post, lecturing in an area of law that he didn’t know very well. This triggered a lot of anxiety, and he became convinced that he was going to be ‘found out’ as a fraud. As result of this, he was studying this new subject for up to 16 hours a day, dropped his social life, stopped going to the gym and was sleeping badly. On top of this he was lecturing more than he ever had.

After about 6 months of this he got a throat infection and lost his voice. Initially he tried to keep going by doing everything but lecturing, but he was so exhausted that he was forced to take to bed. Two weeks later he tried to go back to work, but found his voice was unreliable and he still felt very weak. Since then it had got a little better, but his voice was still hoarse and unreliable, and he still felt exhausted and stressed.

A CBT formulation

A CBT formulation has three key parts – the three Ps. What are the Predisposing, Precipitating and Perpetuating factors of the client’s distress? In Scenario 1, David has clear predisposing and precipitating characteristics (see Table 15.1). He might also have become locked in a vicious circle, where his perfectionist tendencies and his new job conspired to keep him in an activity cycle that was wearing him out—both vocally and generally. The third P, the perpetuating factors, is commonly presented as a framework of physical, emotional, cognitive and behavioral elements (see the lower part of Table 15.1). Together these three Ps make a coherent narrative about why David got symptoms in the first place, and what is now keeping them going.

Table 15.1 Example CBT formulation using ‘the three Ps’.

| Predisposing factors | |

| Prone to distress both mental and physical (may be genetic, early life, etc.) | |

| Perfectionist | |

| Precipitating factors | |

| Major transition | |

| Prolonged period of overactivity | |

| Prolonged period of voice use | |

| Viral infection | |

| Perpetuating factors | |

| Physical factors | Cognitive factors |

| Hoarseness Fatigue Autonomic arousal | ‘I’m not good enough’ ‘I’m going to be found out’ |

| Behavioural factors | Emotional factors |

| Overexertion followed by prolonged rests | Anxious |

| Time off work as the only way of stopping | Stressed |

| All energy going into work and preparation | Frustrated |

Developing and sharing a formulation

Remember that most patients with MUS already have multiple possible causes in mind and are looking for their clinicians to find the right one. The CBT model should include these—but instead of picking one single cause, it includes multiple factors. Developing this kind of model may be unfamiliar territory for some patients. You might say something like this:

Often there isn’t one single thing that causes or keeps these kinds of symptoms going. Usually they start at a period in a persons life when they are overstretched, through work commitments, big life changes or general illness and run-downess. It sounds like in your case…

At this point you can illustrate this by using a framework like the one found in Table 15.1 and start to fill in the various sections of the framework. This could include some of the predisposing and precipitating factors you have identified. It is acceptable to include issues relating to personality, if the person has identified that it may be a factor :

…it sounds like during this time, not only were you under a lot of strain, but you were also pushing yourself quite hard to achieve a high standard, which may inadvertently have put even more strain on the system.

So that covers the first two Ps. Now introduce the third.

Again what we know from conditions like this, is that once they start, it can often be a combination of things that keep them going. I’m going to show you how this works as a vicious circle. So, you say that your voice sometimes goes, and that you get really run down. And when that happens you also feel like this…

Put in here, for instance, that at this point the client gets worried about losing their voice.

And the kind of thoughts that go through your head are that ‘My voice is really vulnerable; if it goes again I’ll lose my job’; and as a result you tend to stop using it and withdraw.

Try to highlight the connections between the factors, showing how the domains interact:

Now it sounds like this has an effect on your mood too, it gets you more down, which probably, in turn, leaves you feeling more run down and your voice weaker.

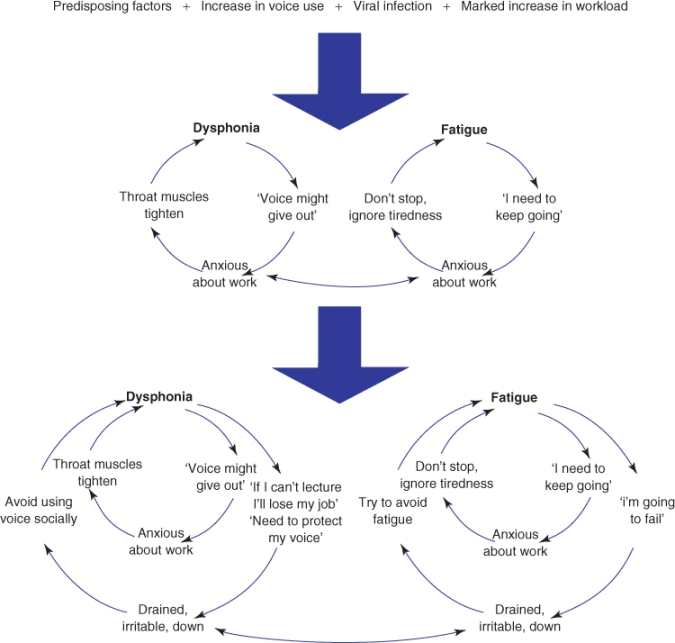

Now add more connections between physical symptoms and thoughts, feelings and behaviour. Figure 15.1 shows how cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviour build up.

Figure 15.1 Vicious circles of symptoms, thoughts, feelings and behaviours. The predisposing and the precipitating factors on the top row lead to the top pair of circles. In turn as symptoms build up then the outer circles in the bottom pair of circles also come into play and may dominate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree